Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | Email | TuneIn | Deezer | RSS

Peter Drahos’ Survival Governance: Energy and Climate in the Chinese Century shows why US corporate-centric strategies, from shale production to carbon capture are a failure. A radically different model has to be embraced.

TRANSCRIPT

LYNN FRIES: Hello and welcome. I’m Lynn Fries. Producer of Global Political Economy or GPEnewsdocs. With me to talk about his new forthcoming book is Peter Drahos.

The global high carbon economy is running out of time and the book Survival Governance: Energy & Climate in the Chinese Century argues that a strong state is required to galvanize a global project of survival governance. Catalytic leadership is needed to shut down the fossil fuel industry and to fast-track innovation in renewable energy.

My guest, Peter Drahos is Professor of Law and Governance at the European University Institute and Professor of Intellectual Property Law at Queen Mary, University of London. He is Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University. Some earlier books include Intellectual Property, Indigenous People and Their Knowledge and Information Feudalism: Who Owns the Knowledge Economy? co-authored with John Braithwaite. Welcome, Peter

PETER DRAHOS: Thank you.

FRIES: Peter, as this book draws on an extensive interview process that was part a larger project on the global governance of energy at the Australian National University, at the Regulatory Institutions Network or RegNet, start by telling us something about that.

DRAHOS: Here we owe a great debt of gratitude to the Australian Research Council, which is the independent body for the funding of research at Australian universities. It really backed myself and a small group of researchers. And they were very generous. They essentially gave us funding for nine years. And so, we were able to really drill down into all of the key countries on energy policy.

Our main focus was essentially government people and people in industry. They were our primary targets. And we did this over a period of nine years. We began interviewing just before the Copenhagen Climate Conference. I was surprised at how frank people were in the way that they spoke to us. People were genuinely worried about the slowness of progress. In the words of one climate negotiator that we spoke to, you know, he said that the real problem here was that governments were not being honest with their publics about the scale of the problem. And I think at the end of that process, I think that’s actually very true,

FRIES: You introduce two concepts in the book: survival governance and the bio-digital energy paradigm. Explain what you mean by those concepts. And let’s start by taking with survival governance first.

DRAHOS: Well, I have a very simple definition of it. It essentially means that states and non-state actors begin to think about preserving and maintaining ecosystems because their survival depends on it. So, in the end if we don’t preserve ecosystems, we jeopardize our own survival.

We need really big picture thinking. And that I think requires states now to use their powers of regulation and to use their powers of financing to encourage and support and foster innovation in the directions that really matter. And what I argue in the book is that those directions are summed up by this idea of the bio-digital energy paradigm.

So, the energy part of that is clear. It has to be renewable energies. The digital part that is that we have to use the language of software to make the generation, the transmission and the distribution of renewable energy as efficient as possible and as market competitive as possible. So here, you know, digital technology can help us to trade in renewable energy. It can help us keep an eye on our own energy consumption. There are lots and lots of different ways in which by digitizing the trade of energy, the generation of energy, we will get to our goal of a world of two degrees or less, much more quickly.

And the bio part of that comes from the fact that we don’t just have the language of software at our disposal but we also have the language of DNA. Now we understand so much more about how organisms are put together, how organisms replicate, and we can intervene in organisms, in DNA in ways that we couldn’t before. Now, of course, genetic engineering, you know, has to proceed cautiously. But many of these technologies have been around for a long time. And so, the idea for example, of using bacteria to produce medicines, for example, is something that’s well known and understood. So, my argument here is that biology has a lot to contribute to the generation of renewable energy, the regeneration of ecosystems.

What we need is what I call the bio-digital energy paradigm, a kind of integration and convergence of biology, of computing science, and of renewable energy. That is the paradigm for the 21st century in just the same way that coal and oil turned out to be the great big scientific paradigm of the early 20th century. We have to get rid of that paradigm we have to shut it down. We need a new paradigm.

FRIES: To create this new bio-digital energy paradigm, you say much more than strong leadership from a state is needed but that a two-degree limit to global warming is not feasible without strong leadership from one or more states. You argue that state power to issue commands with structural effect on the economy and to create money on a vast scale is fundamental. But on the book’s criteria, state powers of regulation and financing that you have mentioned are not even enough. What is also needed is network leadership and a large domestic market. And not many states meet that criteria.

DRAHOS: Here I’m speaking about state leadership. So, I ultimately or rather my position here is that we need one or more states to get the ball rolling to catalyze, to provide some leadership. So obviously, I’m not excluding the participation of many states. But in the end, some degree of state leadership is needed here.

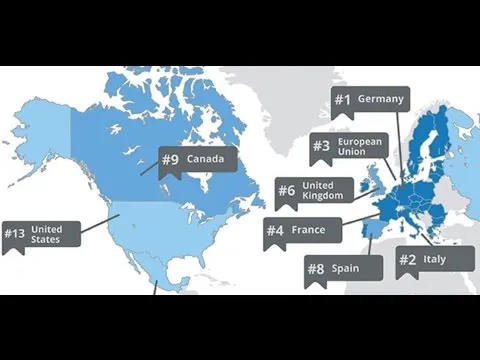

And I think there are really only four possible contenders here for this leadership. The United States, obviously remains a very innovative economy. China, the European Union, because in my book, I essentially think of the European Union as this unitary actor which it is on matters of energy and trade and so on. And finally, India which is another potential player in all of this. So, what I do then is to look at those four states in turn.

FRIES: When the book’s published and people can read it, not many people will be surprised that of the four states you find that the US has the greatest capacity to get the ball rolling to move world capitalism into global governance mode and to create a new bio-digital energy paradigm. But in your evaluation the US is not the most plausible candidate to do so. Give us a glimpse into the thought process of how it is that you came to this conclusion that the most plausible candidate to do so is China, not the US, the European Union or India.

DRAHOS: One of the questions I asked myself was, well, how would you achieve a bio digital energy paradigm? I mean, what would be the levers? And what I argue in the book is that it’s cities that are essentially the levers here. I mean, if we think of large cities, most of the world’s population now lives in cities. And indeed China, as we all know is urbanizing. And you know by 2030, I think roughly another 300 million Chinese people will be living in cities.

So, my argument is that cities represent markets. And citizens in cities will want cheaper energy. They will want clean energy because they will want to live in cities that don’t have air pollution. They will want to live in cities where flooding is not a problem or floods are managed. They will want to live in cities where there are green spaces. Because green spaces are important to us as human creatures in all sorts of different ways. They will want to live in cities where they can easily recharge their cars, where perhaps, public transport is well managed and so on. So there, there are lots of things that citizens want for their cities. And my argument is that the bio-digital energy paradigm can be constituted through the demand for all of the technologies that make up the bio-digital energy paradigm through the demand created in cities.

So, it’s city demands for these technologies that will create the paradigm. And I think China with its many, many different kinds of cities really has an opportunity to take the lead in developing this paradigm. And I think if one looks at what China is doing with its cities, it’s very interesting to see the kind of large-scale experimentation that’s taking place in China. So, you know, Chinese cities vie to be the hydrogen city or to be the eco city or to be the forest city or to be the sponge city.

So essentially what China is doing is trialing many technologies that are relevant to the bio digital energy paradigm at the city level. Because that is the scale at which these technologies have to work. And so, if you can make the technology work at a city scale level, then that makes it easier to roll out across to other cities and then indeed across the world. So, cities in a sense are at our best hope, I think.

Chinese policy makers really came to understand the need for a shift quite early on. I mean if you have a population of 1.3 billion people and you’re burning a lot of coal as China has done you very rapidly run into problems of acid rain, of severe air pollution of generally producing toxic chemicals that poison your environment. And you know, Chinese scientists already in the 1980s were warning about this. So, China ultimately used coal to electrify its economy.

But as early as 1990s, I think it’s interesting that they were already scouting around for ideas about how to shift into a different kind of economy. And so, I think a lot of the groundwork for the shifts that we see taking place in China today, were the product of policy discussions that were taking place in the 1990s.

FRIES: And of the other four players, let’s turn now to the European Union. In your scenarios, the EU has an important role to play as a potential strategic partner with a fast-moving China in both global and regional projects of survival governance but not as a catalytic leader. Explain that.

DRAHOS: When one looks at the EU, it’s a very plausible candidate for catalytic leadership on climate change. I mean, a lot of good things have come out of the European Union. I mean, if you look at their Energy Union Package of 2015, they also have done very good things on pushing the idea of the circular economy forward.

And of course, you know, the European Investment Bank in Europe is funding many energy initiatives, climate related initiatives in the EU. So, I think there’s a lot to be said for EU leadership here. And of course, the EU Commission is talking about a Green New Deal.

My worry about the EU is that it is made up of a lot of states. Of course the UK has departed. But still, the Member States of the EU each see their position a little differently. So, middle European countries like Slovakia or Poland or the Czech Republic have a different view of energy security, perhaps, to how Germany might see it or how the Dutch might see it.

So, everything is a matter of negotiation within the EU. And ultimately the EU can only move as quickly as those very intense negotiations among all of its Member States allow it to move. So, while I think the EU has done and will do very important things on climate, I ultimately think it cannot provide the kind of catalytic leadership that is required.

FRIES: Turning now to India, here you see sectoral successes in innovation and development, the two clearest cases being in pharmaceuticals and software. But what you find much less clear is whether or not India can move with the speed and scale required. And in the book’s scenarios you argue and this is a quote, that: whether they know it or not, India and China are partners in survival governance.

DRAHOS: At least that’s the argument of that scenario. I mean, I do believe that India will pay attention to China’s success stories with cities. Because India too is undergoing a process of urbanization and more and more poor people will leave the countryside of India and will shift into cities. So, I think India has the same chance to scale technology. And for India, frugal innovation is even more important than for China. Because you know, the GDP per capita of India is around $2000 US dollars and China is in the order of $8,000 dollars. So, India has many more poor people.

And we also know that India is also very much vulnerable to climate change so some of the highest temperatures, you know, the failure of monsoon seasons. All of these things now are openly discussed as threats for food security, for Indian agriculture. So, I think the Indian policy makers will study China’s success stories.

India, historically speaking has always focused on, I mean obviously under Gandhi and then Nehru and so on, there was this tradition, Democratic Socialist tradition I think, in which poverty alleviation was seen as important. And India does have a track record, I mean most obviously in pharmaceuticals where it has a very good pharmaceutical industry that over the years has been able to create quite dramatic price drops in medicines. Making it available to more poor people, not just in India but around the world. So, I think if we really care about equality, we have to think about innovation in price terms.

It’s not enough just to come up with an innovation that is priced out of most people’s reach. Ultimately, what is the point of that? So, I think India and China with their poor populations understand that. And of course, you know, there are many neighboring countries. I mean think of Bangladesh and think of Pakistan, countries that also have large populations of poor people. So there are, I think, huge opportunities to target innovation at the reality of poverty.

FRIES: To target innovation at the reality of poverty you argue a new model is needed. To briefly quote from the book you say that: “Under the current globalized model of US innovation, intellectual property monopolists rather than markets diffuse innovation. Monopolists are interested in monopoly rents and so restrict diffusion. This model is essentially a death sentence for hundreds of millions of extremely poor people in the world surviving on less than $2 a day. The same might be said about the half of the world’s population surviving on less than $6 a day. In fact, monopoly models of knowledge asset diffusion are not successful models for anybody but the super-rich.”

DRAHOS: It’s a completely bankrupt model of innovation. I mean, in what world can poor people, either in China or in India afford cancer drugs that are hundreds of thousands of dollars? I mean, US citizens can’t afford these prices that are being delivered.

And what’s more, if one looks at the pharmaceutical industry, there’s been an abject failure to innovate in areas like antibiotics, where we actually desperately need innovation. But I also think the same is true in other areas. I mean the idea that proprietary software, for example, should be protected through intellectual property rights, when the Open Source revolution has demonstrated there are other ways in which we can have software innovation and actually superior innovation is another case in point.

Or think of the price of books. Think of that most precious knowledge contained in books that are priced by publishing cartels around the world at absurd prices. No poor person in China or India can afford the price of a textbook that essentially represents that person’s yearly income.

FRIES: Peter, you’re an expert on Intellectual Property Rights that lie at the heart of the current globalized model of US innovation. Very briefly give us some of the backstory of the path taken in US innovation since the 1980s and the Reagan Presidency.

DRAHOS: Reagan really made it his mission to combat what he called the evil empire. And so unsurprisingly much more research, in a sense, was devoted to technologies that insured US security. So nuclear power is obviously right up there as part of that agenda. And so, it was a time in which both the coal and oil industries, in a sense, were doing better.

And of course, you know, Reagan understood as previous presidents had that US security depended profoundly on innovation in weapons. And it’s very important to emphasize here that every single president after World War Two understands that US security depends on weapons innovation.

And so, the push by Reagan here was essentially to do everything that he could to ensure that the US economy stayed ahead in the innovation game. And so, one strategy for that in a sense was to elevate protection for US innovation through creating a global intellectual property rights system. So, we saw under the Reagan administration, intellectual property being linked to the trade regime.

And that essentially made it harder for other countries to enter the innovation game because once you strengthen monopolies on a global basis it follows that that other countries find it difficult to compete. And it also meant that more investment was likely to take place in the United States, thereby keeping the US ahead as it were in the weapons innovation race.

So that 1980s era was really profoundly important in terms of what happened to the future of renewables. And the way in which the U S weaponized, in effect, the trade regime and sent innovation down the security path in a way that was more intense than had previously occurred.

The U S. ultimately prizes weapons innovation above all else. And so, the incentives for the United States to change the existing way that innovation is done, I think, are reduced. One can see why, they would not want to lead essentially on new approaches to innovation.

And I think the trade war between the United States and China really captures a lot of the concerns that the United States has about the way in which potentially its position as an innovator in military markets could ultimately be compromised. Because what we see there is the United States accusing China of essentially stealing U S intellectual property.

And if we look at the areas where the United States has real concerns it’s in areas like digital technology, artificial intelligence, the whole area of semiconductor chips, neuralnets [neural networks] and so on. And all of these things ultimately have a weapons dimension. I mean, 5G technology is another example where, you know, that is infrastructure that is very relevant to cybersecurity, for example. So, the United States has a lot of incentives to keep the existing paradigm in place.

And in a sense, it’s thrown down the gauntlet to China. And it’s saying, you really have to do much more on intellectual property rights than you have been doing. And if one looks at the past 30 or 40 years, what we see is that every time China complies with a U S demand on intellectual property, it’s not enough. The US comes back with further demands.

You know, one can see this in the way that the United States is rolling out new trade deals. The trade deal, for example, with Mexico and Canada, in which, for example, there are now many more provisions on trade secrecy than have ever existed in any trade agreement previously.

So essentially the United States is saying that the main game for the United States is innovation as it relates to our power in the world. And climate change and survival governance and all those things are very much further down on the list of priorities.

FRIES: On the back of US monopoly models of innovation, even before getting to the book’s critique of the globalized model of US finance, it is not so hard to understand why in the book’s scenarios the US is not a likely candidate to provide leadership in fast tracking innovation in renewable energy and in the rapid diffusion and scaling up of low cost, low carbon technology. Whereas China probably has more of an incentive to re-think the current winner take-all pricing models for technology that US corporations have globalized.

To get at why in the book’s scenarios it is also unlikely that the US will manage its fossil fuel industry out of existence in anything like the time needed, comment on innovation in the US oil & gas industry. Take the US fracking industry, a so-called US success story in innovating a way out of energy dependence. The argument in the book being that the US through innovation has turned itself into a fossil fuel superpower. And that US oil and gas industry innovation is a major stumbling block to getting onto a path to keep global warming under two degrees.

DRAHOS: That ultimately for me is the critical point. That the oil and gas industry in the United States presents itself as a success story. And it’s a success story that has brought wealth to many people in the United States that have never seen wealth. I mean, if you look at where the great shale plays are in Texas and so on, many poor people have in the United States have benefited from deals that they have struck with frackers. After generations of poverty, if a chance comes along to make money for your family, you would jump at that chance.

And so this is why I argue in the book that no US president can really close down the oil and gas industry. Because it is a success story by its own standards and by the standards of entrepreneurship that prevail in the United States.

But I think what is perhaps not fully appreciated by people is just how much the US has progressed in terms of energy security. Obviously after the OPEC oil crisis, energy security was on everybody’s lips. And that was always the dream. Well, the dream in a sense or I would say the nightmare has arrived in that the fracking industry has essentially turned the United States into both an oil exporter and a gas exporter.

And you know that is an example of successful innovation. Whatever else you say about the fracking industry in the United States, it did through a process of incremental innovation find ways to extract fossil fuel from shale. However, it’s innovation that we don’t need. It’s innovation that’s gone in completely the wrong direction. So, I argue in the book that this is innovation that we need to shut down.

FRIES: And Peter what if India or China move in this direction?

DRAHOS: India has something like the fourth largest reserves of coal in the world. If India chooses to exploit those then I think it’s going to be very difficult to reach the kinds of climate goals that climate science is recommending. So, India really is at a turning point and its decision will affect the rest of us.

And China has very large reserves of coal. And indeed, if it adopts fracking technology, it can also have the kind of or potentially it could have the kind of shale gas and shale oil revolution that the United States has had. I mean, there is a complicating factor here relating to China’s geology. And that is that the fracking would have to be at much greater depth than occurs in the United States. And that makes it technically more complex.

So China could choose to go down the path of fossil fuel security. Obviously, if China does that and the United States continues on with its fossil fuel exploitation then I think we can more or less completely forget about the possibility of a world less than two degrees. We would really then shift into worlds of three or four degrees. And at that point, if you look at the scenarios, they’re very, they’re terrible scenarios. Essentially, you’re really talking about collapsing ecosystems and major problems with food production. It really, it really is something that we need to avoid at all costs.

FRIES: Peter you talk to a lot of industry experts, what do they think about the strategy of making coal cleaner by capturing the carbon emissions from coal-fired power stations and storing them underground – so carbon capture storage or CCS?

DRAHOS: That was really one of the stunning findings I think of the interviews. So, we spoke to people in the coal industry. We spoke to manufacturers in the chemical sector. We spoke to very large utilities, for example, in the United States. And one of the things that really surprised me was the cynicism about carbon capture storage. And in essence, as one interviewer said, carbon capture storage is a sort of parasitical form of generating energy.

Because in order to capture the carbon, you have to essentially use energy to capture the carbon. And then once you’ve captured it, you then have to use more energy to send it somewhere for storage. And the simple effect of that is it raises the cost of energy. Coal really no longer becomes competitive with solar. I mean even coal energy or coal generated electricity that doesn’t use CCS is actually these days not really competitive with solar. But with CCS it’s completely uncompetitive.

So, any country that pretends that CCS is the solution is essentially locking itself into a scientific research agenda that is first of all, going nowhere because no one seriously thinks if it’s going to work. And secondly, it’s actually locking itself into a highly inefficient form of energy generation.

FRIES: In the US, Carbon Capture Storage is a key plank of the Democratic Presidential candidate’s climate plan, the Biden Climate Plan. And on China, Biden’s campaign rhetoric echoes that of Trump. The book argues the US oil and gas industry among other super rich networks have played an effective game in preserving the existing paradigm that’s served them so well. In the US, however Green New Deal Democrats are working to break through this and to rally enough support to move the US in a rapid change of direction.

DRAHOS: Ultimately the future lies with the bio digital energy paradigm. And so, in some ways, if China were to move perhaps one happy consequence of this would be that the United States might come to its senses. And move down the path of a Green New Deal and really harness that kind of innovation capability for which really it has a marvelous track record in many ways.

One of the big issues for me personally is that so much of scientific talent over the last 50 or 60 years has been wasted on weapons manufacture. That is such a tragedy. And of course, this all began as a result of scientific participation in the building of the nuclear bomb. And the continued participation of scientists in the building of nuclear weapons. And now in the building of algorithms that essentially create all sorts of automated weapons and automated systems of surveillance. That ultimately makes us more insecure and not more secure.

FRIES: You say it is not comforting to conclude as your book does thatthe world’s best chance of avoiding a climate catastrophe rests on the planning and decisions of China more than of any other capitalist state. And in the book, you talk about the many ways in which things can go very badly wrong. You mentioned one earlier in the conversation notably if China were to go down the path of fossil fuel security. What’s another that you find especially worrisome?

DRAHOS: One that I worry about a lot is if this very negative framing of China by the United States continues. And I think we should recognize that we live in a world of self-fulfilling prophecies. I mean, if people in America continually demonized China, well, the obvious effect of that will be that China will become much more hostile and less likely to cooperate with the United States. But more importantly, it will elevate the hawks in China. And that, it seems to me increases the risk of conflict. And, you know, history teaches us that hegemons and would be hegemons end up fighting. I mean, think obviously of the American Revolution.

FRIES: For this segment, we are going to have to leave it there with more to follow at a later date. Peter Drahos’ new book Survival Governance Energy & Climate in the Chinese Century will be published in early 2021 by Oxford University Press. Once again, many thanks to Peter Drahos who joined us from Canberra, Australia. And from Geneva, Switzerland thank you for tuning into this episode of GPEnewsdocs.

End TRANSCRIPT

How creative is the intelligensia, especially when it avoids dealing with the elephant in the middle of the living-room paradigm! With regard to global overheating and environment degradation, the simplest way of reducing greenhouse gas production is population reduction. The human race has to stop having children for about two decades. Give the overpopulated earth a chance to breathe! Let today’s infant population grow to maturity, about 20 years, then let them produce the inheritors of today’s human race! A 20 year pause in the production of babies would allow substantial reduction in the world’s population, the burning of fossil fuels, the pollution of the oceans, and the burning of the world’s remaining forests.