This interview was originally published on March 8, 2015. On Reality Asserts Itself, Mr. Franklin discusses the strengths and weaknesses of Malcolm X.

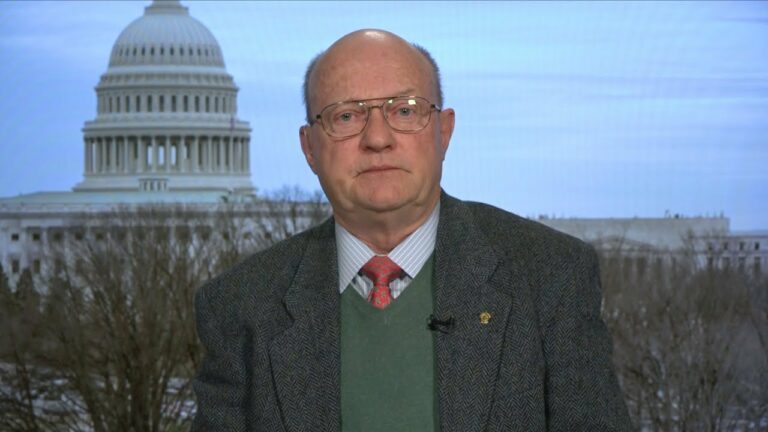

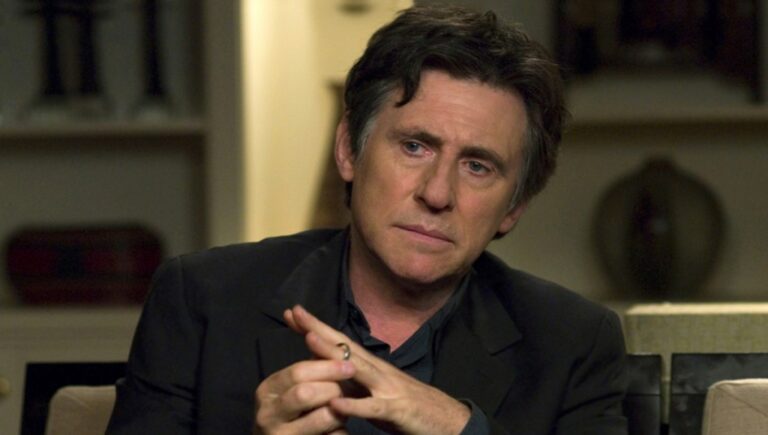

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to The Real News Network and Reality Asserts Itself. I’m Paul Jay. And we’re continuing our series of interviews with Kamau Franklin. He now joins us again in the studio. Thanks for joining us again.

KAMAU K. FRANKLIN, ATTORNEY AND ACTIVIST: Thank you.

JAY: So, just quickly, Kamau currently serves as the southern regional director for the American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker social justice organization. He was previously a leading member of the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement. Thanks for joining us.

FRANKLIN: Thank you.

JAY: So why was Malcolm such a transformative figure for you and countless others? In terms of his theoretical clarity, if you will, only two–he described himself only two years or so before he was assassinated as being a robot in terms of the influence of the Nation of Islam and the way he kind of had bought into this whole cult. He was still grappling with many questions about what to do next, the relationship of the African-American movement to the overall movement, strategy, tactics. It wasn’t that he had this clear vision of what to do next or where to go. On the other hand, he’s a completely inspiring, transformative figure for you and many others. Why?

FRANKLIN: I think some of it is what you just said. It’s that Malcolm openly was willing to change. Malcolm was openly willing to confront things that he thought needed to be changed, not only about him, but general society. And he was a powerful dude. I mean, he is somebody who said what people were thinking but would not say, right? And he said it strongly, and he said it–as he would say, he made it plain. And I think that kind of thing, it wasn’t sort of something for academia; it was for people who were working-class and poor folks. And some of it was clear in terms of which way forward. And I think even as Malcolm in his last year and a half sort of battled what next for himself, partly he wanted to stay within the Nation, and that was part of his battle was to create a strong black-led organization that can advocate on behalf of black people. And I think that, with some clarity, was something that Malcolm sort of gave all of us. And rhetorically speaking, a lot of times I’d tell people that I want to hear their rhetoric these days, because unless you can do it better than Malcolm, there’s no reason for you to talk about it. Now it’s about doing, right? And I think Malcolm gave us that sort of clarity around who we are as a people, our history, our background, where we came from, what has been done to us. And I think he also, though, pointed in some ways which way forward in terms of the type of organization and organizing that needed to happen. And lastly I would say that–I said this at some other point, that Malcolm has been very sort of poorly talked about in terms of his organizing skill and apparatus. I think, in terms of my own organizing, particularly when I was in my 20s, Malcolm became a model of someone who taught you how to go fish for people, taught you how to motivate people, taught you how to get people in a room and how to talk to folks and get them to believe that they can make changes in the world. And I think that’s what makes him so powerful for me and a whole bunch of other people, that you felt like this is somebody who was talking from their own personal experiences, that may or may not to come very close to things that you’ve experienced, telling you how they’ve changed their lives and how they’ve made a difference in their lives and how you can make a difference in how you’d see the world and do things in the world.

JAY: Like all leaders, especially leaders who die, there’s a great battle over interpreting and fighting over the real meaning of so-and-so. And I hear two–I’m sure there’s more than two, but two basic kind of camps I hear is that Malcolm is the representative, leader of the fight against white supremacy, and others that say he fought–and by the end of his life it was white supremacy, but white supremacy is a product of a capitalist system, so he’s also anticapitalist, where that first camp sort of imagines even a black capitalism would be okay, ’cause the real problem is just white supremacy. What do you make of that?

FRANKLIN: Well, I think usually people break it down into whether or not Malcolm remained a nationalist, right, whether or not Malcolm X was devoted first and foremost to organizing within the black community, and whether or not Malcolm became an internationalist and so, therefore, thought that the more important thing was to organize amongst all different sets and groups of people and include black struggle within that. So if I were in a camp, I think it’s–I’m probably more in that Malcolm was a nationalist to the day he was assassinated, that his experiences led him to understand and believe that you have to work in solidarity with other folks and other groups, and, obviously, that this sort of, like, the–take away some of the harsh sort of racial rhetoric that he learned and preached in the Nation of Islam. Right?

JAY: All whites are devils and such.

FRANKLIN: Yeah. Yeah. I think Malcolm still had hostility towards white people in general, as other folks who knew him would say in other books and interviews that I’ve seen, that he was a harsh critic of what he saw as white America’s continued dominance, arrogance, and oppression against black people, but I think he’d moved to a point where he wanted to work with everyone and anyone that he thought was interested in solving the problem. And I think the battle lines become whether or not Malcolm can be claimed. I think there are a lot of folks in the socialist camp who began sort of reinterpreting Malcolm and sort of had the first sort of post-Malcolm assassination opportunity to write books about Malcolm–and George Breitman is a perfect example–to write books about Malcolm and talk about what his worldview was becoming. And I think that led us down a path of who was Malcolm at the time of his assassination, which again is hotly debated within organizing political circles still to this day when people speak about Manning, speak about the book that Manning Marable wrote, and people sort of contest that with other writings about who Malcolm was at the time of his assassination and what he was becoming.

JAY: I mean, in terms of what he was becoming and who he was, he was still forming his ideas about things. So he can be an inspiring figure without–it’s not that he’s Moses came down with some tablets with the truth written on a piece of stone.

FRANKLIN: I think most–and I think anybody who reads Malcolm to sort of figure out which way forward. I think there’s enough there for us, too. Whether or not Malcolm had all the answers, right, sometimes I think that’s a strawman built by folks who are trying to knock him down. I personally don’t think Malcolm had all the answers. I think he was trying to figure it out as he went. But I think, again, one of the things that were his most sort of interesting or important about Malcolm is that he tried to build a black organization of some consequence that was working-class and poor in terms of who its membership were, that talked about ideas around black self-determination and control, and then that later also talked about ideas of working with all sincere people to solve issues and problems. I think that roadmap that was set out was something that’s broad enough for a lot of us to sort of, like, say, hey, that’s something that we can follow and get behind, but obviously not specific enough for us to sort of resolve all the issues that are about society.

JAY: You wrote a chapter in a book that Jared Ball and Todd Steven Burroughs did, a collection of articles in the title: A Lie of Reinvention. And in your article you have–. I don’t know if you would call it criticisms. It’s more things you consider either weaknesses or limitations of where Malcolm was at. So let’s talk about some of them. So you write: some of the more humanizing aspects that Marable–and your chapter’s essentially–the whole book’s actually a critique of Marable’s book on Malcolm–Marable could easily have explored include the following: why Malcolm continually allowed himself to be sidetracked and drawn into a fight with the Nation of Islam. After leaving that organization, that no-win situation distracted him from his work and increased hostilities on both sides. So talk a little bit about that. I mean, what were examples of that, and why did he?

FRANKLIN: Well, I’ll start on why he did it: because he got into a personal war with Elijah Muhammad. I mean, as some folks who would now write, Malcolm discovered or found out that Elijah Muhammad was having affairs with young secretaries and having babies. And Malcolm’s first instinct was to try to protect the Nation of Islam and its leader by coming up with a story, based on biblical text and the Quran, as to why this was acceptable. But once it was found out within the Nation that Malcolm was talking about this, trying to figure out plans to sort of in some ways cover it up, to be honest, that it was looked upon as none of Malcolm’s business, and particularly for those who were looking for a way to either punish Malcolm or move him out of the Nation anyway ’cause they felt he was trying to take the Nation in a direction that they did not want the Nation to be taken into. And what I mean by that is that Malcolm wanted to take the Nation to be on the front lines of black struggle, as opposed to being sort of a prototype capitalist organization in which some of the money sort of went up to the top. But what happens with it, who knows? People benefited from it, people got big houses. Some folks wanted that to stay. Right? So that became a basic feud. And that feud was exacerbated, obviously, by government infiltration and the FBI, which they take credit for, the split between Malcolm and Elijah Muhammad, of helping to keep it going.

JAY: They put some fuel of the fire, but there was stuff there.

FRANKLIN: No, there was real stuff there. And I think part of what the distraction that it became for Malcolm is that instead of building new organization that he wanted to build, he got into this back-and-forth with this powerful organization where he had little resources to sort of defeat it and/or to protect himself.

JAY: Well, it’s also, is it not–I can’t–me sitting here psychoanalyzing Malcolm X, but I host the show, so I will. Part of his own separation, it’s not that much time since he thinks Elijah Muhammad has a phone to God, I mean, is God’s representative on earth. So unpacking that relationship from him is not an easy thing when you’re so far into it.

FRANKLIN: No, not at all. But, again, by being stuck in it, by engaging in it to the degree in which he did, I don’t think he started it, but I think because of Malcolm’s personality he was willing to sort of end it, right? He was willing to go blow for blow, and he was not willing necessarily, even if one day he might have decided he wasn’t going to pursue this sort of fight or struggle anymore, the next day he was back into it. And I think obviously the Nation did things to prod and to keep it going. The Nation of Islam called Malcolm’s home and threatened his wife and threatened his family with death. They refused to let him keep the home that he lived in for probably ten years, in terms of his work with the Nation, because the deed was never in his name; it was in the name of the Nation.

JAY: And they probably figured, well, we gave you the platform to get famous, so you owe us.

FRANKLIN: Yeah. Yeah. So they–.

JAY: And we gave it to you, we can take away.

FRANKLIN: Yeah, and we can take away your life, too. And so in some ways, obviously, that puts you in a certain psychological mode of protecting yourself and your family. But I also think that it’s a destructive mode when it sort of hampers this person who was thought of as a leader of a larger community who actually had larger duties to take care of, not only family duties, but community responsibilities in terms of what he was doing and was professing and the role that he was on. I think this sort of being stuck in that fight–and I’m not saying it was easy get out of it, but being stuck in that fight was sort of detrimental to what could have happened.

JAY: Alright. You go on to write, why Malcolm believed that Elijah Muhammad or any human being was more than human, and in fact divine. Indeed, Islam may have offered him a spiritual path out of the muck and mire of drugs and street life, but it also blinded him from drawing needed conclusions earlier and led to his downfall.

FRANKLIN: Yeah. I mean, I think–this is my own personal opinion, right? I’m not someone who subscribes to any religion or spiritual practice. But I think–and I think Malcolm in his autobiography talks about this a lot in this final chapters, that he puts so much faith in another human being, so much of his will and his time and his devotion was not just to the organization, but to the single individual and what he thought this individual meant in a spiritual way, that it blinded him to the faults of this particular individual, which made it so much more startling or dramatic for him when he thought that this individual was somehow–when he figured out that this person was not as divine as he had once thought he was. And for someone like me that’s–it sort of–it makes sense in a–you know, it’s like, why would you think of that in the first place? But when someone is looking for a way to survive and to sort of pull themselves out of a situation–someone once, I remember, quoted as saying that if you’re drowning, you’ll grab on to the sharp edge of a knife if you can get pulled out. And this is not to suggest that the Nation of Islam has not done what I would consider really good work in the black community, but I also think there is a limit to what it can do because of some of its spiritual beliefs about what the religion of Islam can do for us and/or any religion.

JAY: You also write: –why Malcolm made so many openly contradictory statements on the way forward for black people in America and the world. For example, although publicly he would say he was willing to work with a wide array of groups, he was continuously bashing those groups–not a very good way to create unity. A lot of people kind of speculate that he looked like he was on the path to maybe where he and Dr. King might have even teamed up in some way.

FRANKLIN: I think there was a possibility of that. I think Malcolm started doing things like–he went to Selma in ’65, he had conversations with Dr. King’s wife. I think he wanted to be more involved in the traditional civil rights movement, but on his own terms. Right? So, for Malcolm that wasn’t necessarily just about passing legislation, although he thought that was a part of it. It was more than just sort of breaking down laws for sort of equal treatment. It was about what the resources are that are going to be coming into the black community and who controls those resources, what are the institutions that need to be built within the community.

JAY: And we’ll get into that more later. But you write, while he talks about that, he continues to bash. What is that?

FRANKLIN: I think he couldn’t help it. I think it’s just part of his personality. I think, for Malcolm, he had such a problem with what he thought was the sellout position of many folks in the civil rights movement who were willing to–either wanted to become prominent people or get paid by sort of the state or not [crosstalk]

JAY: It wasn’t just bashing. There was truth to all that.

FRANKLIN: Yeah, there was a lot of truth to it. But on the one hand, if you’re going to say that you want to work with some of these folks, if one day you’re trying to work with them but the next day you’re calling them Uncle Toms, it’s going to be a hard-working relationship.

JAY: Did he stop critiquing King?

FRANKLIN: No, I don’t think he ever really did. I think he tried, right, I think he made probably an honest and earnest effort to try, but I think he fundamentally had different beliefs than King. Even the practice of sort of nonviolent civil disobedience was something that for Malcolm X, sitting down to get fire hoses blasted on you or potentially getting hit over the head was something that he just could not sort of sustain or fathom or figure out. It was: you are a human being, and if someone tries to attack you, you don’t sit there and take it; you either respond in kind or you get out of the situation, right, that that’s no way for any human being to try to gain their quote-unquote freedom or liberation. And only in America would someone suggest that black folks, based on our treatment here in America, need to, again, continue to sort of succumb to that kind of treatment in order to get our freedom. I think it was antithetical to anything that he believed in and continued to be until his death.

JAY: Although it’s kind of interesting. Near the end of Dr. King’s life, at least in terms of his analysis and public positions, he becomes far more radical. The end of Malcolm and near the end of King, they feel like they’d be a heck of a lot on the same page.

FRANKLIN: I think when you think about foreign policy, and even some domestic policy issues, they may have had different tactics about where they wanted to go, but I agree that politically they both started thinking about some similar things. And I think Dr. King was influenced by the black power movement to a degree that’s underplayed today, because everyone is stuck on trying to present a 1963 version of Dr. King in the March on Washington, for obvious reasons, right? Those in charge don’t want you to see a radicalized Dr. King who’s challenging–.

JAY: Yeah, but the revolutionary King, who essentially denounces–connects the war abroad with poverty at home and capitalism.

FRANKLIN: Yeah. And they don’t want you to see that King, right? And that King matches up well with Malcolm intellectually. You could see those folks joining together with a whole bunch of other people in some stated purpose.

JAY: And that would be a threat, a real threat.

FRANKLIN: Yes, that was definitely a threat.

JAY: And you can imagine why people would want those two guys dead.

FRANKLIN: Yeah. I mean, there is an important FBI COINTELPRO document that talks about–again, that takes credit for exacerbating the feud between Malcolm and the Nation, basically destroying the closest thing to, like, the leadership of a black militant movement, and then making suggestions of who could follow, and then, later on, them talking about who they should put in not only Malcolm’s place, but Martin’s place, as to who should be leading the black movement. So they took–obviously, they took these folks seriously in terms of what they could do in changing, in bringing people out into the community and having people be a force for trying to change what their conditions were.

JAY: And if you take your point, how much the black power movement influenced Dr. King, and the black power movement is so much an outgrowth of Malcolm,–

FRANKLIN: Yes. Exactly.

JAY: –you wind up with how much Malcolm influences King.

FRANKLIN: Yeah. I think many people say that the movement came into the ’60s belonging to Dr. King and his–those related to him, but it certainly exited the ’60s a lot closer to Malcolm X’s position, line of thought, and sort of personality, sometimes, again, to, I think, our great advantage, but also sometimes to our detriment. I think sometimes those of us who get politicized in that way are so interested again in re-creating sort of the rhetoric of Malcolm that we forget about the strategies and work that not only Malcolm, but the largest civil rights and black power movement had around changing conditions.

JAY: Okay. In the next segment of our interview, we’re going to talk a little about self-determination and its relationship to the people’s movement. Please join us for the continuation of Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network.

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter

“Kamau Franklin is the founder of Community Movement Builders, Inc. Kamau has been a dedicated community organizer for over thirty years, beginning in New York City and now based in Atlanta. For 18 of those years, Kamau was a leading member of a national grassroots organization dedicated to the ideas of self-determination and the teachings of Malcolm X. He has spearheaded organizing work in various areas including youth organizing and development, police misconduct, and the development of sustainable urban communities. Kamau has coordinated and led community cop-watch programs, liberation/freedom schools for youth, electoral and policy campaigns, large-scale community gardens, organizing collectives and alternatives to incarceration programs. Kamau was an attorney for ten years in New York with his own practice in criminal, civil rights and transactional law.”