This interview was originally released on April 23, 2014. On Reality Asserts Itself, Mr. Lander assesses Chavez’s attempt to establish a participatory democracy that changed the structure of power and decision-making.

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay, and this is Reality Asserts Itself. We’re continuing our series of interviews about Venezuela.

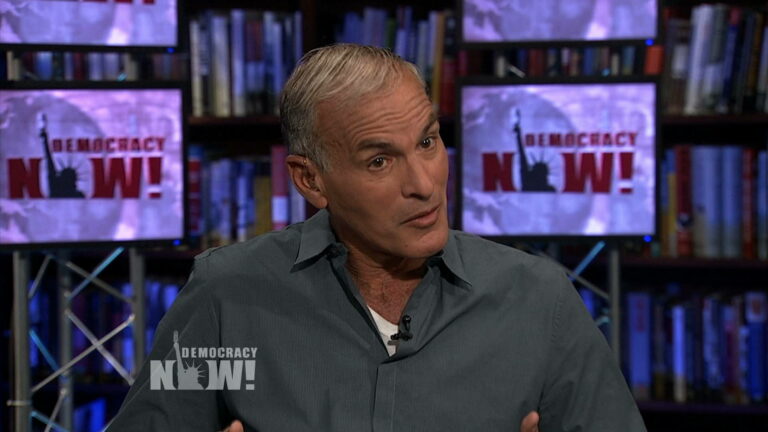

And now joining us again in the studio is Edgardo Lander. He’s a sociologist and professor at the Central University of Venezuela in Caracas.

Thanks for joining us again.

PROF. EDGARDO LANDER, UNIVERSIDAD CENTRAL DE VENEZUELA IN CARACAS: Thanks for inviting me.

JAY: So there’s formal democracy, and then there’s the actual real practice of democracy in any country, and the United States is a pretty good example which looks like there’s supposed to be formal democracy, but the reality of it is quite different. But the promise of the Venezuelan revolution was to really deliver participatory power to ordinary people, that the whole structure of how decisions were made was going to change. So how successful have they been?

LANDER: The results are mixed. On one hand, it’s obvious that there has been a huge transformation in popular political culture in the sense of empowerment, in the way people are able to organize and deal with things in their own lives. There have been many, many instances of mechanisms of participation relating to water issues, to health issues, to transport issues, to zoning issues in the barrios, etc., that have been quite successful. And Venezuela has a level of grassroots organization that it never had before. And that’s a plus. I mean, that’s–and that change in political culture is enormous, and it’s there, and people are willing to fight for it.

But, on the other hand, there’s many obstacles, there’s many limits. One limit has to do with a sort of a conception of socialism, a state-centered conception of socialism, which leads to a very vertical type of decision-making, both in the party structure and the state structure. That has to do with something we talked in another segment, about the economic base of democratization. If you don’t have a transformation in the economy and democratize the economy as such, then there’s serious limits to what participation is about. You can have a lot of participation and decisions made elsewhere, which is not–.

JAY: So, I mean, we’ve talked about this on The Real News a lot in regards to the United States or relation to the United States: a concentration of ownership leads to concentration of power. But that can happen even in a place where you–if you wind up with a state owning the only business in town–and that’s the oil business–then you wind up having a somewhat similar concentration of political power.

LANDER: Yeah.

And there’s also another very important issue in Venezuela that helps to explain why the Venezuelan society is so divided politically, apart from the class issues. It’s the fact that many of the proposals of participatory democracy that had been sort of experimented or carried out had been very sectarian. And I’ll explain myself.

If you were going to create a communal state and have communes and communal councils as the sort of base of a new model of democracy as an alternative to representative democracy, you have to guarantee that this is a mechanism of belonging and participation that’s open to everybody, because it’s the base for the whole of society. But for a lot of government officials and party officials, their vision of the communes and the communal councils is that they’re Chavistas. If you have a deeply divided country and you create the mechanisms for a participatory democracy that from day one excludes, say, 40 percent of the population, there’s no way you can possibly construct democracy on that basis, and there’s no way you can sort of have stability and continue it in the long term, because you left a whole proportion of the population out. And that’s been a constant debate within the government and within the party, and a lot of social movements have really been very active in reacting to this sectarian vision in which you have to be Chavista to participate in what’s supposed to be the universal base of the new society.

JAY: Chávez, in a few months before he died, when he came back from Cuba after being treated, he seemed to have actually–have done some reflection on this point and actually did a kind of self-criticism that some of the rhetoric had been–against the opposition had been, first of all, including too many people in the critique, calling people escuálidos and things. And he seemed to be aware that this had been a mistake and something should–it should be corrected, but it was not long after that he passed away.

LANDER: Yeah, nothing much has happened in that respect. I think the fact that the government continues with this discourse of calling the whole of the opposition fascist, for instance, doesn’t get them anywhere. It unifies opposition. There are obviously some fascists and U.S.-backed, very right-wing people who are active in the /mar?k?z/, that’s true. (b06:20) But if you lump everybody together and you don’t recognize that there’s widespread oppositions within the opposition, then you just lump the opposition together and it will eventually grow bigger.

JAY: Now, President Maduro had a piece in The New York Times just a few days ago which seemed to call for peace, call for negotiations. He actually–there’s none of that kind of tone in there of kind of just denouncing the opposition. I mean, do you think there’s a change of trying to be more inclusive? ‘Cause I know he was trying to have talks with the opposition. In fact, it was the opposition that was refusing to get involved in any of the talks.

LANDER: The thing is that Maduro’s leadership is weaker than Chávez’s leadership, and his capacity to lead this type of shift in policy is not what would have been the case with Chávez. There are many people in the Chavista movement that are completely against this type of negotiation or sort of soft position [incompr.] and consistently denounce Maduro for being too weak.

JAY: I think it’s a very important point that even under Chávez, he was managing a movement with many different groups and factions, political organizations, and ideological trends. It wasn’t like–I mean, he appeared to be fully in control, but, you know, he actually had to, you know, play to the base, in a sense. But it was a very complicated mix of forces on his side. He couldn’t just say, do this and do that.

LANDER: Well, more or less. But at the same time, once he decided something, he could sort of guarantee that he had consensus. And Maduro can’t guarantee that consensus. So Maduro has been giving very mixed messages [incompr.] this issue we’re talking about. One day he talks about the fascists in the opposition, and the other day he talks about the need to–he’s very spiritual when he’s–so he talks about spirituality and sort of the meeting of the opposites or whatever. I mean, he just talks on and on about this sort of–. And people make fun of that, some of the radical Chavistas. So it’s–you get a very mixed messages, and it’s not a consistent policy that you can say, oh, this is what has been decided and that’s what’ll be carried out.

JAY: Now, in the barrios, the pro-Chavista forces are far, far in the majority–at least–

LANDER: Yeah.

JAY: –they were whenever I was there,–

LANDER: Yeah.

JAY: –and I assume that’s still the case. So these–.

LANDER: In most places.

JAY: So these people’s councils–and I assume everyone knows barrios are these big, big areas of shantytowns, the poor. But many, many people are working-class there and have jobs and go to work every day.

The people’s councils, then, or these communal councils, while you can say they might be sectarian, it’s a very small amount of the people that actually would fall on the opposition side. So most of the people, more or less, could be included in these councils. Do they have any power? Have they changed the way decisions are made in the barrios?

LANDER: If you go to a barrio where there’s a council and you ask people whether they aren’t worried about the fact that they have no autonomy, that they depend on government financing, whatever, they will tell you: for the first time ever, we got together as a community; for the first time ever, we sort of set the limits–this is where a community starts and ends; for the first time ever, we had an assembly, communal assembly, and we elected our own leadership; for the first time ever, in assemblies, as a community, we decided what our problems were; for the first time ever, we decided what our priorities were; for the first time ever, we decided what investments would be necessary; for the first time we were ever able to talk to different government organisms [sic]–water, health, whatever–in order to solve those problems; in many cases for the first time we were able to carry out the projects ourselves, self-manage projects, financed by the government, but [incompr.]. What’s autonomy about? I mean, it doesn’t make any sense. What I’m describing is an ideal situation, which has happened in many places, but that’s not generally the case, necessarily.

So it’s very full of tensions, conflicts, and back-and-forths. Nowadays, even in the most Chavista barrios, you still get 20 percent, 30 percent people in the opposition. So it’s a big issue if you have a communal council where it leaves 20 percent or 30 percent out. And as a model for the organization of society, you need to have a situation where anybody can be included and the differences in Venezuelan society can be processed at every level, including the grassroots level.

JAY: So what’s the reasons for such sectarianism? ‘Cause it seems rather obvious it would work better if it was more inclusive.

LANDER: I think it’s a very mechanical motion of class difference, even if in this case it’s not class. It’s a conception of politics that was very present in Chávez, in which you are either with me or against me–enemy/friend conception of politics. And this discourse of sort of separating the opposition was very useful for Chávez, because it led to the possibility of creating this enormous solidarity and this sense of belonging in the Chavista base. And it really helped the process. I don’t agree with it, but it really was useful for those political purposes.

But it tends to backfire eventually, because it not only solidifies support, but it solidifies opposition as well, actively.

JAY: So are there political forces in Venezuela that want to defend the gains of the Bolivarian Revolution who see or share some of the criticism that you have of how the revolution’s being led? Where do you/they go, in the sense that I assume, you know, the [kind of] people I’m talking about don’t want to join the opposition, because the opposition, you know, although it’s a mixed bag, the leadership of the opposition seems to want to take Venezuela more or less back to the Washington Consensus kind of neoliberal agenda in one way or the other? On the other hand, is there room within the Bolivarian movement to be able to say these things and contend on these issues?

LANDER: It depends on the political situation. In general, there isn’t that much space. There is a web page called Aporrea, which is sort of the web page for debate, for Chavista debate. And you could see sort of fluctuations at times, sort of looked into the content of the debates and correlate the opening or closing of the debate with a political situation. When there’s an extreme polarization and a sort of more dangerous situation from the point of view of the government, in terms of stability or threats, then debate really gets reduced. When there’s–after the political defeat in some election, or when there’s less threat, than there’s–tends to be more opening in the debate.

One of the things that I think is significant in the way social organizations have–react to the government is the degree to which these organizations preexisted Chávez or not. A huge proportion of the organizational process at the grassroots level in Venezuela has been created through the Bolivarian Revolution. So, for many people it’s their first experience in political [incompr.] organization. But at the same time, all the previous organizations that existed, people have experience and people have conflicts and people have political sort of conceptions of their own. There were struggles against the traditional labor unions or whatever. And people that had this previous experience tend to be much more critical and much more demanding of further democracy, of more autonomy for grassroots organizations and in general. Some people sort of grew up in the Chavista movement.

JAY: And I would think the kind of things that are happening in the streets right now make it far more difficult to actually have this kind of debate,–

LANDER: Yeah, of course.

JAY: –’cause it polarizes things so much.

LANDER: Yeah. That’s one of the main problems in Venezuelan society over the last 15 years, that there’s a lot of issues that are just left out because of polarization. I mean, in Venezuela the drug issue’s not debated. The oil issue’s not debated. Abortion is not debated.

JAY: And I know it’s not a–I don’t think it’s an apology for the government to say that while there’s lots of weaknesses and mistakes of the government, the Venezuelan elite and the Americans are doing everything they can to make sure all the focus is on this kind of disruption and [crosstalk] don’t get a chance to work out some of these issues.

LANDER: Absolutely. Absolutely. I mean, the role of the media–international media is just obvious, the way they handle the issues.

JAY: I said in the opening of the first segment that you can make all the critique you want, but the hypocrisy of the U.S. government having as an ally Saudi Arabia or Israel and other places–.

LANDER: Or itself.

JAY: That’s even–best, itself.

Okay. We’ll end it there. Edgardo has agreed–this is the beginning of a discussion. We are not going to unpack the whole of Venezuela in one series. Edgardo has to get back to Venezuela, but sometime in the next few weeks we’re going to pick it up again while he’s there, over webcam. And hopefully sooner than later he’ll be–we’ll get him back to Baltimore as well.

Thanks very much for joining us.

LANDER: Thanks for inviting me.

JAY: And thank you for joining us on The Real News Network.

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter

“Edgardo Lander (born 1942) is a Venezuelan sociologist and left-wing intellectual. A professor emeritus of the Central University of Venezuela and a fellow of the Transnational Institute, he is the author of numerous books and research articles on democracy theory, the limits of industrialization and economic growth, and left-wing movements in Latin America.”