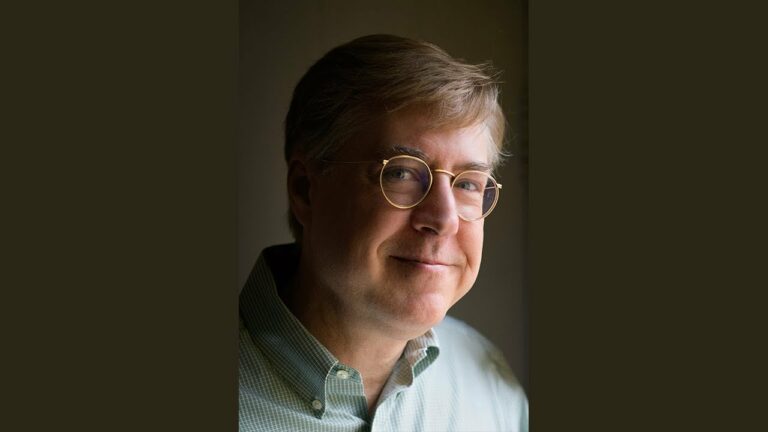

As Trump vows to resume nuclear explosive testing, Hans Kristensen — Director of the Nuclear Information Project at FAS, the world’s most authoritative source on global nuclear arsenals — joins host Barry Stevens for an urgent conversation. Kristensen calls the move “chest-thumping,” with no strategic justification, warning it would likely trigger a disastrous chain reaction of testing by China and others.

Barry Stevens

Hi, I’m Barry Stevens, and welcome to theAnalysis.news. In a few moments, I’ll be speaking with Hans Kristensen, and we’re going to be talking about nuclear weapons, Trump’s promise to resume testing nuclear weapons, and what’s behind the current nuclear arms race. So don’t forget the donate button and to subscribe to our channel. Thanks.

Joining me now is Hans Kristensen. Hans is the Director of the Nuclear Information Project with the Federation of American Scientists in Washington, D.C.. His work focuses on researching and writing about the status of nuclear weapons and the policies that direct them around the world. He’s co-authored the Nuclear Notebook since 2001, which you can see in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

I’d say that his work is the definitive source for up-to-the-minute information on nuclear weapons around the world. He does this along with his colleague, Matt Korda, who actually has appeared on theAnalysis.news with Paul Jay. I believe that Hans’ team was the first researchers to spot by satellite new ICBM silo construction in China. So, Hans is also a frequent advisor to the news media on nuclear weapons and policy. So welcome, Hans.

Hans Kristensen

Thank you very much. Thanks for having me.

Barry Stevens

Now, a couple of weeks ago, around Halloween, Donald Trump posted that the U.S.A. was going to begin nuclear testing. I’ll read his post. “Because of other countries’ testing programs, I have instructed the Department of War to start testing our nuclear weapons on an equal basis. That process will begin immediately.”

Now, it wasn’t clear to me whether he meant explosive testing or delivery systems, because President Putin, of course, had just made a big public splash about testing some of his wonder weapons delivery systems. But then, President Trump seemed to double down on explosive testing. So, if so, what was your reading about that? Does it worry you? Is it a bad idea?

Hans Kristensen

Yeah. So, for the first three days after he said what he said, people in the administration and everyone were trying to figure out what he meant. So this is sort of a trademark of Trump that he says something, and then people have to figure out what it means. In this case, now, after some time, it seems that he was indeed talking about some degree of nuclear testing in the sense that not the way we tested nuclear weapons during the Cold War with a full-scale nuclear explosion, but some degree of testing that produces a small yield. Because this has been the U.S. moratorium since 1992, that has self-imposed this moratorium, that it would conduct nuclear weapons experiments, but it wouldn’t conduct them in such a way that they created any form of yield of nuclear material, fission.

Barry Stevens

When you say yield, you mean explosion?

Hans Kristensen

Yes. A nuclear explosion where the power, the explosive yields come from the fission process. This is what makes nuclear weapons so unique. They can produce an enormous amount of power from the fission process and fusion. So, after a while, it became clear that what he was coming from was that there had been intelligence reports back in 2019 that Russia, at some point before then, and they were not explicit when it was, after the 1980s up till 2019, Russia, supposedly or allegedly, had conducted a small number of nuclear tests. Not full-scale nuclear test explosions, but smaller-scale tests that had produced small yields.

This is not new, and he has not presented additional information. You haven’t heard anything from the intelligence community that substantiates these claims back from then, since. They also express some concern about more activities at the Chinese nuclear test site, but they didn’t say explicitly, “The Chinese are doing this, too.” So, this is where we are.

We can imagine that what he’s been given is a briefing about Russia doing this, and China potentially might conduct some experiments, too, or something, and then he’s gone off from that. Because you have to remember, this was a statement that was given during his trip in Asia, right before he had a summit with the Chinese leadership. So you could imagine that he felt it was necessary to appear strong before that meeting in some shape or form, but like you said, he’s doubled down on this after.

Barry Stevens

So, just to sort of jump from this thing, so Russia, is it true? I mean, you would-

Hans Kristensen

We don’t know.

Barry Stevens

We don’t know because, I mean, I would have thought that seismic readings and the other ways that one measures whether a test has taken place would be available outside the intelligence community, or am I wrong about that? Are we just taking the word of the U.S. intelligence community, or do we have evidence outside?

Hans Kristensen

No, there’s a public, so to speak, a global network of seismic stations that have been built since the early ’90s to do this, to check nuclear tests. Are there any seismic signals coming from them? They’re very good, these networks. They can detect seismic tests down to a nuclear explosion that is one kiloton less than one kiloton, just below one kiloton. In comparison, the nuclear bomb that destroyed Hiroshima was 15 kilotons. So, just under one kiloton is a very small yield.

Barry Stevens

So it is true that Russia did this?

Hans Kristensen

Well, so that we don’t know. There’s no seismic information that says, “Whoa, look at this. The Russians did something at Novaya Zemlya.” There’s nothing that has been recorded that I’m aware of that we have seen in public.

From a technical perspective, a military perspective, a very low-yield nuclear test like that is no big deal. I mean, it’s not like this is an experiment from which they get significant new scientific or military valuable information. It’s important for maintaining their nuclear weapons and also some basic physics science. But it’s not like they, therefore, take a secret leap in nuclear weapons technology or something like that. So, this is the status we don’t know more than we knew in 2019, I would say.

Barry Stevens

Right. So, how much of this is propaganda displaying like an elephant pawing the ground and putting out its ears? “Here I am. We’re so tough. We’re exploding nuclear weapons.” How much of it is something that the military is actually saying, “Jeez, we need to test these weapons to make sure they work?”

Hans Kristensen

Yeah, let’s make it clear. The military is absolutely not saying we need to test nuclear weapons with an explosion, nor is the nuclear laboratory saying that that is necessary to maintain the safety, security, and effectiveness of the weapons we have in our stockpile. There’s no technical or military reason to do this. This sounds like it is entirely a sort of political chest-thumping from Trump.

So, that would be a big step back from the United States if it stopped its moratorium, of course, and started producing experiments that have a yield, a small yield even. It’s not like the United States would get some significant new science from an experiment like that that would make it worthwhile. On the contrary, the cost-benefit analysis here quite clearly is that it would be extraordinarily counterproductive, because there’s no doubt that if the United States violated its own moratorium, all the other nuclear-weapon states would start testing nuclear weapons as well, and they would not necessarily keep them at very, very low yield.

Other countries would have a significant interest in resuming nuclear testing. China, because it tested relatively few compared to the United States and Russia. So they have a real interest. India and Pakistan also very much so. They’ve only conducted a small number of nuclear tests, and would definitely want to test more weapons to develop more advanced nuclear weapons.

Barry Stevens

So you’re saying that there is a reason for China, India, and Pakistan to test, but not for the United States? I mean, technically and militarily?

Hans Kristensen

Yes, they would gain something significantly from more tests.

Barry Stevens

You said this was chest-thumping. Well, what’s the harm of a bit of chest-thumping? Do you think it makes the world more dangerous?

Hans Kristensen

Yes, it does. If the chest-thumping leads to a resumption of nuclear testing in other countries, for example, China, which is now high on the U.S. potential threat agenda, that would have real implications for their capabilities and their ability to build more advanced nuclear weapons in the future. It’s also an issue for India and Pakistan because, of course, they’re in their own arms race. This sort of bilateral arms race between the two of them. That could take off and enter a whole new dimension if they started developing more advanced nuclear weapons.

Combined, these developments would add to the pool of things that are not going well on nuclear and international security issues. They would help fuel the fan, if you will, fuel the fire that’s already going.

Barry Stevens

Yes.

Hans Kristensen

That is one that has been evolving significantly over the last decade and a half, to such a point that we are now in an openly adversarial military and political environment with China and Russia. That’s taking extra steps every week where they’re turning up the heat on each other. So this would be a problematic thing to throw into that pool of troublesome developments.

Barry Stevens

Yes, and the Trump gang or the Trump advisors, they’re thinking is that we have to display strength so that they back down, but of course, in an arms race, the opposite can happen.

Hans Kristensen

Yeah. Well, when the other countries are demonstrating strength, that doesn’t mean that the United States says, “Ooh, we’re now scared. We will back down.” Why would they do it? They’re large military and economic powers. They have no reason to back down whatsoever. So no, that’s not how it works. It may feel good for a little while. You can go home, and you can give some interviews and say, “We showed them. We’re standing up to them, la-di-da.” But the outcome of this, cost-benefit-wise, is big. That’s like shooting yourself in the foot, literally.

Barry Stevens

Yeah. There’s been a film recently on Netflix called A House of Dynamite. I’m sure you’re aware of it. I couldn’t stand it myself, but the metaphor of A House of Dynamite was interesting. I think it actually came from Carl Sagan’s metaphor of we’re living in a gasoline-soaked room and are arguing over who has more matches. That I think was more or less what he said, which I always thought was quite evocative. I think Oppenheimer’s metaphor was two scorpions in a bottle.

At any rate, it does seem that these people don’t realize the consequences of a global thermonuclear war, which seems incredible because I would have thought everybody does, but to take that risk seems extraordinary. You talk to these people. What’s on their mind? Why aren’t they more scared of an arms race that they’re initiating?

Hans Kristensen

They are scared of nuclear war. They’re scared of nuclear weapons. That is one common theme. The problem is that people react differently to that scare. Some people say that, because nuclear weapons are so terrible and dangerous, we really need to get rid of them fast. Other people say, “You’re right, they’re really scary and dangerous. That’s why we need to keep them as long as others have them.” So, you end up in two very different camps coming out of the same fear.

With the chest-thumping and the nuclear posturing that we’re now seeing taking off on all fronts, the theory is that by doing that, by making yourself stronger, by standing up to the adversaries, by threatening them more, because that’s what deterrence is, and strengthening deterrence is about threatening more, the theory there is that then they will behave. They will not use nuclear weapons. Of course, that’s the same message we gave them 10 years ago. It didn’t make them stop. It didn’t make them back down.

On the contrary, everything we did 10, 20 years ago fed into their perception of us being a threat to them and so forth. So, this treadmill of threatening action, reaction, we’re on that, all these countries. It’s not like two scorpions in a bottle. It’s more like three large nuclear-weapon states with 15,000 nuclear weapons on a small planet. Good luck with that.

So, that’s just where we are, but this is the big dilemma of deterrence. That if you don’t have a grand strategy, if all you really have is just chest-thumping, deterrence, more weapons, more offensive operations, and more posturing, then all you accomplish is just turning up the heat. At some point, I think somebody will look at it and they will say, “Gee, this is not really giving us this outcome we were hoping for.”

On the contrary, things have gotten a lot more dangerous. That is how people started thinking twice about the Cold War, because, of course, this basic mentality was the same back then. “Just build some more stuff. Threaten them more, then they will think twice.” It didn’t happen. Instead, it produced more and more scenarios, situations that were more and more dangerous. We are reliving that bad movie from the old days.

Barry Stevens

So sooner or later, they’ll figure out that it’s not a good idea, and they’ll back down. However, in 1983, one of dozens of examples, the military exercise Able Archer made the Soviet leadership think that the Americans were using the military exercise as a cover for a genuine nuclear strike on them, and they were preparing to strike themselves. There are so many instances of this, as you well know. 1962, of course, and the October Crisis with Cuba, came very close to a worldwide nuclear war. At any rate, you can imagine this happening again, these kinds of very close calls or even disasters, catastrophes?

Hans Kristensen

Oh, yeah. There’s no reason to assume they will not happen again. Every time you make your military and nuclear posture more aggressive, a quicker reaction, or more in your face, you make it harder to manage those situations if they happen because timelines for reaction are shortened. Threat perceptions are overblown. Worst-case scenario assumptions are all the time.

So, that’s one of the problems here, that too much deterrence paints you into a corner where you have to act or react in a certain way. It’s important to find a balance where you’re not rattling the nuclear sword more than absolutely necessary. We’re going beyond that point now. I would say we, it’s not just the United States, it’s the United States, China, and Russia. So, it’s a big problem, how you stop that dynamic.

Barry Stevens

How would you suggest stopping it? What can we do in the political West?

Hans Kristensen

Well, so the first step for stopping it is not to continue to take extra steps. I mean, we’ve made our point. We don’t have to field more nuclear weapon systems or make them more capable of destroying them before they can destroy us. We’ve made that, the arsenal. We’ve done that. We’re in each other’s faces. We have those capabilities. Adding new technologies will not help improve the security situation, but it will turn up the perception on the other side that you’re out to get them. You’re looking for new ways where you can win, we can get an edge, and they have to take their countermeasures to it.

So, the first step is to stop taking more steps. That is hard to do when you’re in a national security environment in which your entire foreign policy, certainly international security, conversation builds on being able to repeat the word strengthening deterrence. We’re strengthening deterrence. That is the entire mantra right now.

Barry Stevens

Isn’t it also true that there’s always been a faction within the U.S. military that has believed that it was possible to fight and win with nuclear weapons?

I’m thinking of back in the ’50s, Curtis LeMay, who was head of Strategic Air Command, had a plan to attack the Soviet Union and China first, just kill 600 million people out of the gate. Nuclear warfighting has been discussed in various ways, and the idea that they’re now building theater nuclear weapons. I believe there’s a cruise missile on a submarine that’s going to be built.

Hans Kristensen

That’s the next one. Yeah.

Barry Stevens

Yeah. So, doesn’t that indicate that some people in the Pentagon and maybe in other centers believe they can fight and win a nuclear war? Am I wrong?

Hans Kristensen

Yeah, it depends on what you mean by winning, because the problem here is, of course, that it’s easy for planners to draw up scenarios in which we don’t start the nuclear shooting, but if the shooting starts, we will respond in ways in which we can terminate the hostilities on terms that are to our benefit. That means, to a large extent, hunting down and destroying an adversary’s nuclear forces before they can use them. There are other targets, groups, and sets, but that’s the sort of core of it.

That’s how nuclear warfighting can get you into an autopilot mode where you have to get better and better and better all the time to be able to execute that strategy. Because the essence of it is that you have to be able to get the adversaries’ nuclear forces before they can use them. There is no one that I’m aware of in the U.S. military today who believes that the United States can execute a decapitation-first nuclear strike out of the blue against Russian nuclear forces or even Chinese nuclear forces.

Barry Stevens

But it is their doctrine to use nuclear weapons first in a conflict, or at least-

Hans Kristensen

No, not necessarily.

Barry Stevens

I mean, it’s not definitive, but they’ve never ruled it out using nuclear weapons first.

Hans Kristensen

Yeah. In the United States, the nuclear planners and policy doctrine wonks don’t like to rule out scenarios. So, their theory is, if you avoid ruling out scenarios, then the adversary, at least, will not be able to say, “We can confidently conclude that they’re not going to do that over there. So let’s focus on the other things.” It keeps other countries on the edge. They’re uncertain about what exactly it is we would do. Therefore, the theory goes, they would be less hesitant to try to take the step that we don’t want them to take.

But no one imagines that you can sort of decapitate the adversary. A smaller nuclear country like North Korea, okay, yeah, absolutely, but large nuclear weapon states, no. The objective here is not to do it in that way. The objective is if it starts happening, and frankly, I don’t know people in the United States military that I’ve talked to who are in favor of using nuclear weapons first out of the blue. Not at all. That’s not the intention.

The intention is that if hostilities happen, and it reaches a level where escalation to nuclear is beginning to happen, or where we are just fundamentally losing a conventional war that is important enough to us, in that case, they want to reserve the ability to use nuclear weapons first. They also want to say, suppose someone has a biological attack or a large-scale chemical, but mainly a significant biological attack that is killing hundreds of thousands, millions of people, the United States, according to this thinking, would want to keep the option to use nuclear weapons. That nuclear weapons used would, by definition, be first because the adversary would have done a biological attack, not a nuclear.

Barry Stevens

Yeah, but other countries have had a no-first-use declaration. China, I believe, has.

Hans Kristensen

Yeah, China has one, and India has some sort of no-first-use. For a period after the end of the Cold War, Russia also had one, but that didn’t last long. So today, it’s only China and India that officially have nuclear no-first-use policies. Of course, the problem with no-first-use is how can you trust it? I mean, it’s a good gesture, but so what?

I mean, if you got into a war and that country was about to lose or were being attacked in a way that hadn’t gone nuclear, but they were still losing, why would they not use nuclear weapons to defend themselves? It’s not like they would say, “Oh, gee, we have to lose now because we can’t use nuclear weapons first.” I mean, all countries will use the means at their disposal if the future of the state’s survival is at stake.

So, in my view, the value of no first use is not the constraints it puts on what a country will do in a war. The value of it is the less military requirements for what the military has to plan for. Because the official policy is that you do not have to plan our nuclear forces to be able to go first. So, our alert level can be a lot lower. Our capabilities to strike this and that don’t have to be as advanced. I think it can have a calming effect on a country’s posturing in peacetime, but we shouldn’t have any illusions about it if war breaks out that is at a level where nuclear weapons come into use.

Barry Stevens

Yes. Let’s talk specifically about China because it’s pretty apparent that, since and maybe before the second term of President Trump, there’s an increasing belligerence towards China and perhaps vice versa. But you hear even serving officers saying, “We’re already in a war with China,” and some very loose talk. And the Secretary of Defense… should I call him the Secretary of War?

Hans Kristensen

No, he’s still the Secretary of Defense.

Barry Stevens

Yes. But he said some very belligerent things. And there are people in the Pentagon, I think Elbridge Colby, the Deputy Secretary for Policy. A number of people have talked about, or Steve Bannon said, “Our goal is the destruction of the Communist Party of China.” And of course, it’s the U.S. Navy that drives up and down the East Coast of China, not the other way around. You and your colleagues spotted these silos, and that has been mentioned quite a lot by the Pentagon, this buildup. What’s your view of this particular arms race? Do you see the U.S. as being belligerent here, or do you see China as being equally belligerent? How do you see it?

Hans Kristensen

Yeah, I think both countries play their dirty game. The point being that each has their perspective on why what the other is doing is a danger and a risk, and they have to take military and other steps to counter them. Out of that mindset comes the need for new force structures, the need for new operations, what have you. China, today, is not the China that it was 30 years ago by any stretch of the imagination.

Barry Stevens

Okay, listen, we’re going to be back in a moment with part two with Hans Kristensen. So, watch for that, and thank you very much.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | TuneIn | Deezer | RSS

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter

Hans Kristensen (born April 7, 1961) is director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists. He writes about nuclear weapons policy there; he is coauthor of the Nuclear Notebook column in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, and the World Nuclear Forces appendix in Stockholm International Peace Research Institute’s annual SIPRI Yearbook.