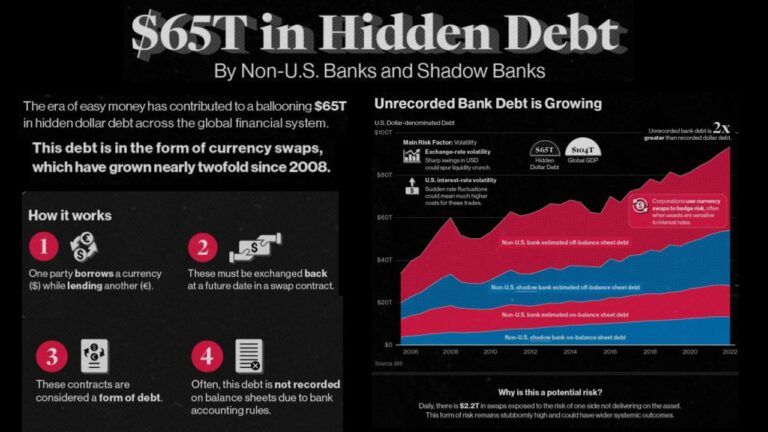

In this video, we explore how Wall Street firms, REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts), and private equity giants are reshaping housing markets—treating homes as hedge funds and tenants as revenue streams. The result? Displacement, skyrocketing rents, and the collapse of housing as a public good.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. What if we took housing out of the hands of corporate landlords and made it public infrastructure—like schools, libraries, and transit systems?

Paul Jay

Hi, I’m Paul Jay, and welcome to theAnalysis.news. This is an essay I’ve been working on, which is about how big banks in the financial sector have made rental housing across North America so unaffordable. Be back in just a second.

Homes or Assets: Why Housing has Become a Playground for Global Capital

Across Canada and the United States, housing is not treated as a basic human need. It has been reimagined as an investment vehicle, a speculative asset class, and a profit machine for institutional investors. This transformation, what housing experts call the financialization of housing, sits at the heart of the affordability crisis gripping cities across North America.

From Toronto to Atlanta, apartment towers and suburban homes are being snapped up, not by families, but by real estate investment trusts, hedge funds, and private equity firms. These financial landlords rarely set foot in the properties they own. For them, rent is revenue, eviction is a business strategy, and maintenance is a cost to be minimized.

The fallout is clear: skyrocketing rents, deteriorating housing quality, and communities hollowed out for the sake of investor returns.

The Rise of Corporate Landlords

After the 2008 financial crisis, Wall Street found its next gold mine in housing. With interest rates near zero and stock markets volatile, investors poured billions into residential real estate. In the U.S., major players like Blackstone began buying foreclosed single-family homes by the thousands, bundling them into securities and renting them out through subsidiaries like Invitation Homes.

Since 2010, institutional investors have acquired over 80,000 homes, though they still own only about 3% of the total single-family rental market nationwide. But in some cities, their presence is far more concentrated.

In Atlanta, institutional investors now control an estimated 27% of single-family rentals. That’s based on data from the Urban Institute.

In Canada, the story centers on apartment buildings. REITs, R-E-I-T-S, and other institutional players now own roughly 25 to 30% of the country’s purpose-built rental stock, according to the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation. CapReit, that’s C-A-P-R-E-I-T, alone manages around 64,300 suites nationwide. That’s a number from 2023, so we can expect it’s larger now.

These landlords run their operations like corporate balance sheets. Rents are algorithmically organized, repairs are deferred to cut costs, and tenants are churned to maximize profits. Ontario’s policy of uncapped rent increases between tenancies actively encourages this cycle of displacement.

The Human Cost

The wave of financialization isn’t just abstract economics. It’s shaping lives. In Canada, 22.1% of renter households are in core housing need, meaning they spend more than 30% of their income on shelter or live in overcrowded or substandard housing. That’s the CMHC number from 2022. Again, likely worse now.

In the U.S., nearly 49% of renter households are cost-burdened, with about 12 million paying over half their income on housing. Again, a 2023 statistic. Highly unlikely to be better, more likely to be worse.

Buildings owned by REITs or private equity firms are more likely to have pest infestations, broken elevators, and mold because maintenance is treated as an expense to suppress. Meanwhile, renovictions, where landlords evict tenants under the guise of renovations, only to relist the units at higher rents, have become a favorite tactic for driving out lower-income tenants.

Public Housing: A Neglected Solution

It wasn’t always like this. For much of the 20th century, Canada and the U.S. built public and non-market housing on a scale large enough to shape housing markets to some extent. In the U.S., the 1937 Housing Act created a foundation for affordable housing, which expanded dramatically after World War II. Public housing peaked at 1.4 million units in the 1990s before Reagan-era budget cuts and programs like Hope VI gutted the system. Today, only about 970,000 units remain, excluding another 2.2 million households relying on vouchers to supplement private market rents.

Canada’s federal government funded significant social housing from the 1950s through the early 1990s, when Ottawa withdrew and left provinces to pick up the slack. Now, social housing represents just 3.5% of Canada’s total housing stock, compared with OECD averages of 7%, and far behind countries like Austria at 23% and the Netherlands at 30%. Those numbers are from an OECD housing database in 2022. Where public housing was well-funded and well-managed, it worked. It works in Europe, and there’s no reason it can’t work here. Where public housing is neglected and stigmatized, it fails, opening the door to today’s speculative profit-driven model.

Public Financing: A Path Forward

Other countries demonstrate alternatives. Germany’s Sparkassen system of municipal banks funds affordable housing while keeping profits in the community. Norway’s Kommunalbanken supports low-cost housing and infrastructure. Even in the U.S., the century-old publicly-owned bank of North Dakota proves public banks can finance housing projects the private sector ignores. By providing low-interest loans for nonprofit, cooperative, and public housing, public banks can shift housing finance away from speculation.

Here’s a practical agenda for housing justice. To reclaim housing as a human right, both countries must embrace bold structural reforms. This can be done at the city level. In the U.S., of course, state governments need to participate. In Canada, provincial governments. But here’s what we need to demand:

– Robust rent protections, end vacancy decontrol, limit rent increases to inflation, and outlaw renovictions.

– Ownership limits.

– Cap institutional ownership per market and tax speculative vacant units.

– Massive non-market housing investment.

– Build new public, nonprofit, and cooperative housing.

– Retrofit existing stock.

– Public finance mechanisms.

– Establish municipal, provincial, and state public banks to fund affordable housing at scale.

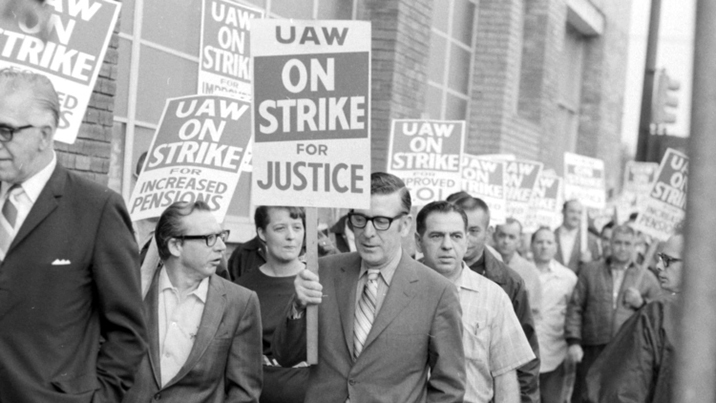

– Tenant empowerment.

– Expand tenant unions, community land trusts, and resident-controlled ownership models.

The Case for Full Public Ownership

But even these measures are just a start. While a minimum objective should be to bring Canada and the U.S. at least up to the levels of Europe’s most advanced models, where countries like Austria and the Netherlands provide 20 to 30% of housing as social or cooperative stock, even that would fall short of true equity. To address the systemic failures of financialized housing, we must think bigger.

All large-scale rental housing should eventually be publicly owned and managed. Small family homes and modest private investments can coexist. But the era of corporate landlords treating entire apartment blocks as speculative assets must end. A system where large rental properties are treated as public infrastructure, like schools, libraries, or transit systems, would ensure housing stability and affordability over generations. It’s the only way to end the extractive business models that have gutted communities for decades.

Homes Before Hedge Funds

The financialization of housing has enriched a small class of investors while impoverishing millions of renters. It’s not inevitable. It’s the result of decades of policy choices. It’s the result of the financialization of our whole economy. The power of big banks and the financial sector has never been greater, the concentration of ownership has never been greater, and the concentration of political power has never been greater. But it can be reversed.

The question isn’t whether Canada and the U.S. can afford to build public housing. The question is, how much longer can we afford the alternative? Housing is a fundamental human right, not just another commodity.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | TuneIn | Deezer | RSS

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter