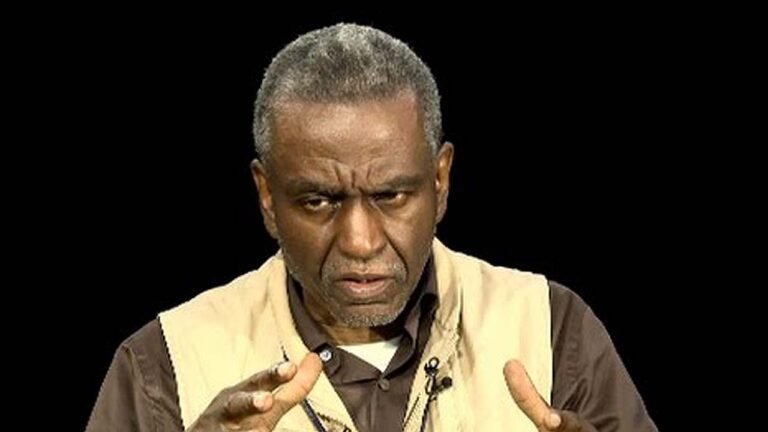

U.S. President Trump has extended the aims of his first presidential term’s “maximum pressure campaign” by slapping additional sanctions on Iran. Djavad Salehi-Isfahani, Professor of Economics at Virginia Tech, describes the detrimental effects of U.S. sanctions on Iran’s economy and society. Salehi-Isfahani illustrates how the sanctions’ differentiated effects often result in them being “invisible” to certain segments of Iranian society, leaving some Iranians convinced that their government is solely to blame for the country’s economic woes. In addition, he asserts that the combined effects of U.S. sanctions and Iran’s policy choices continue to hollow out the Iranian middle class: while the government has assisted the poor with large direct cash transfer programs, it has largely ignored the demands of its middle class.

Can Iran Kick Its Oil Addiction? – Djavad Salehi Isfahani Pt. 2/2

Talia Baroncelli

Hi. You’re watching theAnalysis.news, and I’m Talia Baroncelli. Today, I’ll be joined by economist Djavad Salehi-Isfahani. We’ll be speaking about the effects of U.S. sanctions on Iran. If you’d like to support us, you can go to our website, theAnalysis.news. Hit the donate button at the top right corner of the screen. Make sure you’re on our mailing list. That way, all of our content can get sent straight to your inbox. You can also watch us on YouTube. Make sure you hit the bell. That way, you get all of our notifications or listen to us on podcast streaming services such as Apple or Spotify. All right, let’s get into it with Djavad Salehi-Isfahani.

Joining me now is a Djavad Salehi-Isfahani. He’s a Professor of Economics at Virginia Tech University in the U.S. and is also a research fellow at the Economic Research Forum in Cairo and a research affiliate at the Middle East Initiative at the Harvard Kennedy School. He recently co-authored a book called How Sanctions Work: Iran and the Impact of Economic Warfare, which he co-authored together with Narges Bajoghli, Ali Vaez, and Vali Nasr. Djavad, it’s really great to have you here today. Thanks so much for joining.

Djavad Salehi-Isfahani

Thank you very much for inviting me. I look forward to our discussion.

Talia Baroncelli

U.S. President Trump recently slapped additional sanctions on Iran. He said that he hated doing so but just had to do it in order to prevent Iran from developing nuclear weapons. In response, the Iranian Supreme Leader Khamenei said that Iran would not be threatened or coerced to come to the negotiating table. The foreign minister, Araghchi, recently echoed this sentiment, saying that Iran would not enter into direct negotiations with the U.S. on the nuclear issue as long as they were being threatened with sanctions. I wanted to speak to you about the general effect of U.S. sanctions on Iran and whether sanctions actually have their intended effect, which is something you discuss in your book, How Sanctions Work?

Djavad Salehi-Isfahani

Well, there’s no mystery that the U.S. has economic power. Iran has a particular weakness in that it is an oil exporter, one among many. When its oil exports are curtailed or banned by U.S. sanctions, it will take a hit. The economy will take a hit. Iran depends on oil exports to run most of its production. Capital goods, intermediate goods, and manufacturing suffers. But there are also food imports that are curtailed. The way to think about this is that you have an external shock. A lot of countries do. It’s not something that developing countries are unfamiliar with. Every now and then, their export revenues go down. They lose foreign currency because of capital flight, and they have to adjust to that. It’s called austerity. Iran has experienced austerity, and to the extent that that was the goal of the sanctions. The United States and Europe, they succeeded. They’ve hit the economy relatively hard.

If they wanted to get some foreign policy outcome from it, which is their stated objective to stop Iran from enriching uranium, then they failed miserably because enrichment has increased significantly since sanctions began. The latest wave of sanctions or the ratcheting up of sanctions in 2018, when President Trump, during his first term, left the then agreement, the 2015 nuclear accord between Iran and the world powers, the economy took a dive, but Iran was defiant and was able to increase it’s enrichment so that now it’s reached a very critical point. They have enough nuclear material with 60% enrichment that they can make several bombs, according to the news reports. In that sense, yes, it has failed, I would say, overall.

Let me tell you something, the way I look at this, because you mentioned President Trump again in false sanctions. This has become a habit for U.S. governments. When they find Iran not responding to their initiatives, they find something new to put on the news cycle, like, they have more sanctions. I think of it sometimes as something we are all familiar with when you are at a bus stop, and the bus is not coming. At some point, it becomes very difficult for you to leave because you think you have accumulated enough credit or waiting time that you shouldn’t be leaving now. I think that’s what’s happening with sanctions. Their understanding, American understanding, is that we have hurt the economy so much, and the other stuff is happening, like the war in Gaza and so on. So they think this is now the time when the bus will arrive. We can reap the benefits from sanctions. I don’t see that on the horizon right now. All I see is waiting or Iranian suffering without the bus arriving.

Talia Baroncelli

That’s a good point. People are waiting, and there’s a person who was interviewed in the book, a woman who spoke about sanctions being so present in her life as if it were the weather. The weather is something that’s always in your life. It’s something that you expect to face every day. It’s something that you can’t get rid of. So, in her life, sanctions, always played a role. They were always a factor that she had to deal with. What is the actual punitive or threatening effect of sanctions at this point if they’ve been around for so long? And given that there’s really no prospect for them to be removed, how does that factor into the decision-making? Because if the threat no longer really has the desired effect– I mean, of course, it impacts people’s lives. People have been suffering. People don’t have enough food. There are effects of the sanctions, but if there’s no possibility for them to really be removed, then how does that crystallize over time? And what is the result of that?

Djavad Salehi-Isfahani

That’s a very good question. One of the things that surprised me watching the sanctions over time is that the sanctioners know how to impose sanctions, but they don’t know how to remove them. It’s one of those things. It’s very hard, too, after you have threatened lots of banks and lots of importers not dealing with Iran, to tell them that things are okay now and they can do trade with Iran. That’s partly because when you impose sanctions, it’s not all a legal matter. There is a whole host of NGOs and right-wing think tanks who come in and want sanctions to continue.

Obama removed the sanctions or eased the sanctions, but these NGOs, like United Against Nuclear Iran, FDD– these are think tanks– or groups in Washington would tell other countries, “Don’t get too cozy with Iran. This will not last. Obama is not going to be…”. That was the last term of Obama, so it was obvious that Obama wasn’t going to be around for very long. So removing sanctions is very difficult, and it now has become the main issue because Iranians now have experience with Americans trying to remove sanctions, but they can’t. When Trump says, “Make a deal with me,” it’s not clear what he means.

Talia Baroncelli

Right.

Djavad Salehi-Isfahani

The subtext is that if you make a deal, reduce enrichment, do this or that, then we will remove sanctions, but everybody knows that Trump is very bad with detail. He doesn’t know what it is like to remove sanctions. I’m sure that people who are around him are not the type who would say, “Yeah, that’s a serious issue. Iranians know about it, so we can’t just talk to them like they don’t know anything. Keep saying we have to make a deal. We have to come up with specific proposals. We have to address the shortcomings of the JCPOA.” Trump has been very vague on what was really wrong with JCPOA, other than, “It wasn’t my deal. It was Obama’s deal, so I don’t like it.” But he never specified what it was that was wrong except that it didn’t completely bring Iran to its knees.

When you listen to the right-wing opponents of the nuclear deal or critics of Iran, that’s what they want. They don’t like a state that’s relatively powerful and is defiant in a neighborhood, meaning the Middle East, where the U.S. wants to project its power and keep Israel safe, keep Saudi Arabia-UAE safe, and so on.

Talia Baroncelli

Right. Of course, the U.S. neocons, people such as John Bolton, don’t even want Iran to be a regional power. They’d like to see regime change, and they weren’t in favor of the Chinese-brokered rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Iran. But Iran is in a slightly different position now. Its regional influence has been curtailed to a certain degree, given that it’s not able to fund organizations such as Hezbollah and Hamas to the degree it was before. If you look at the sanctions, would you say that they benefit a certain segment of Iranian society, that they don’t have the same effect across the board, and that perhaps the IRGC, the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps, is able to benefit from the sanctions to such a degree that they don’t even want the sanctions to be removed, they’d actually like to see them continue?

Djavad Salehi-Isfahani

Yes, there’s no question that there are people in Iran, some powerful entities in Iran, that oppose the negotiations with the U.S. I wouldn’t say they are pro-sanctions. They are not opposed to removing sanctions. I think they recognize that Iran’s economy has suffered because of sanctions. They would like it to get better, but they are not willing to pay the price, and they don’t trust the United States. I hear a lot about this term that’s become very popular in Iran, [foreign language 00:11:03], meaning the beneficiaries of sanctions. I don’t know exactly who they are and how it is that people benefit. There’s no question when the government cannot use the market system, global markets, to sell its oil, move products, and bring the money back, that people come in and say, “I can do it for you.” They are protected because of the level of secrecy that’s necessary to evade U.S. sanctions. They can then pilfer some of the money, cheat, and corruption arises. Those people have incentives to keep sanctions on.

People who have developed a specific capital, like Iranians, we’re very good with flying to Frankfurt, making business deals, and coming back with both business and pleasure. Now they have to go to China, and they have difficulty with that. Other people have invested, and they have developed relationships with China. That’s a specific trading capital that they will lose if trade moves back again to Western Europe. I think this focus on the economic benefits of sanctions for specific groups misses the point that overall, the Iranian elite or political elite sees this as a struggle the way anticolonial movements have fought. It would be a mistake to focus too much on this.

I know President Rouhani, who was the president about four or five years ago; he faced a lot of opposition to the agreement he had signed, which I thought was a very good agreement because it allowed Iranians to sell oil, do trade, and so on. I was upset that Trump exited that agreement. But he popularized this term, the beneficiaries of sanctions. I think that’s a simplification. I’ll make one more point besides the fact that there is an anticolonial sentiment in Iran. It’s been there since the British and the Russians were taking liberty with Iranian soil. It was there when the CIA and MI6 deposed the popular Prime Minister Mosaddegh, and it was there when the West, especially the United States, supported the Shah, who had a very elitist group.

Now, the point I’m adding, actually, is during the Shah, globalization relations with the West became synonymous with a large section of Iranian society with rising inequality. This issue hasn’t been addressed. I’ll give you a simple example of the JCPOA. When the JCPOA was signed that week, the Rouhani administration announced agreements to purchase 200 new planes, a very large order. I wonder– by the way, I agree, Iran needs planes. Nobody disagrees with that, but if you look at it from the point of view of the Iranian poor who saw sanctions as higher food prices, as inability to get a job and repair their homes, and so on, the airplanes seem a very loud way of saying, “This is not for you. JCPOA is not for you.”

I would say successive Iranian governments have blamed failure of their economic policies, especially failure to do global trade or come to an agreement with the United States and the West, on these profiteers of sanctions. Not addressing the fact that a lot of Iranians are not quite sure if they’re going to come on top, if relations with the West are resumed or smoothed and Iran becomes, again, like under the Shah, which is the ideal of many Iranians. That’s how they see economic conditions before the revolution and so on.

I guess I’m done with that point that Iranians are not convinced that a nuclear deal will deliver benefits in terms of more oil exports and in terms of freer global trade. They also don’t know if those benefits that are accrued, they go to them, to the section of the population that’s always felt economic growth. Western styled, capitalist growth favors the rich, and they pick up their crumbs. They are now rallying around– some of them are rallying around this movement that we don’t want to negotiate with the U.S. I think that’s a very dangerous situation because, yes, it’s okay not to negotiate with the U.S., but it is very bad not to recognize that trading globally is essential for economic growth. That the people who promised that we can close all the borders and have a robust economy are promising them something that’s not achievable, at least in historical experience.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, some people must be basing their viewpoints on historical factors which you already mentioned. For example, under the Shah, there were wider ties with the Western world. Then prior to that, you had companies like the British Petroleum Company, essentially stealing all of Iran’s natural resources, which led to Mossadegh actually becoming democratically elected because he was opposed to that resource stealing. Of course, they don’t necessarily trust Trump because of his discontinuities when it comes to foreign policy and they obviously don’t trust the U.S. administration under Biden. When said that he would bring the U.S. back into the JCPOA, then never actually did so never actually had an executive order to bring the U.S. back into the agreement. There’s obviously distrust on the part of many Iranians when it comes to the U.S. upholding their side of the agreements they’ve ratified. I’m assuming that plays into the rationale of arguing that Iran should not negotiate with the United States.

But my next question would be, does this mean that some Iranians are more willing to have agreements with China, with Russia, for example, or with other countries who have been sanctioned, who are also at the other end of U.S. sanctions? My last question is also, is this something that’s perhaps affected or motivated the rapprochement between Iran and Saudi Arabia, given that things are always changing, that maybe to have another friend in the region again is something which is perhaps welcomed given aggressive U.S. foreign policy?

Djavad Salehi-Isfahani

Those are several good points, good questions. Let me just make one quick remark about resource looting. Resource looting stopped when oil prices quadrupled in 1973 under the Shah. I think since then, it doesn’t make sense for countries that export oil to equate that with countries like in Central America or Africa, like the Islamic Republic. There’s a lot of resource looting that’s associated with colonialism. Oil-exporting countries got free of that because of stuff that happened in the world oil market around early 1970s. What they are now concerned about is who gets the benefits of the oil. For example, if you live in Iran’s rural Sistan and Baluchestan, a disadvantaged province, there has to be a lot of money coming into Tehran before some of that trickles down. So they are naturally not very enthusiastic about removing sanctions. If you live in Tehran and you have connections with the government, yes, you know, as soon as dollars become available in the central bank, you’ll be one of the first to get it and you could do stuff with it. That brings a heterogeneity in level of enthusiasm about sanction relief and this negotiation with America.

Djavad Salehi-Isfahani

You raised another point about Russia, China, and then Saudi Arabia. Actually, those are very different points. Russia and China are powerful countries and Iranians, I think, are quite aware that becoming a sole client for either one is not good for them. I think one of the reasons why the leadership in Iran is interested in keeping some kind of an agreement with the nuclear watchdog and with the Europeans is because they know China and Russia are better partners for them if they can also deal with Western Europe. Now, when Saudi Arabia comes in, it’s the opposite way. It’s exactly trying to walk away from this dependence on China and Russia that Iran tries to become friendly with his own neighbors. I thought that was a very good move because you have Saudi Arabia during the JCPOA negotiations as vehemently against negotiations and sanctions relief as the Likud in Israel.

Now, they have been able to reverse that. How they have done it, I think, is in part by brandishing their military power and hitting targets inside Saudi Arabia. Saudis recognize that you have to be okay with your neighbor, especially if it has weapons and countries thousands of miles away, like the United States, can’t quite protect you. I think this is a very important understanding. Iran did use China to get the agreement to establish diplomatic relations with Saudi Arabia, but I feel that Iranians are with the Chinese with an understanding that China is also in some sense, an Imperial country. It throws its weight around in Africa, in South Asia, and it’s not going to be the best friend with Iran. Iran is a weak country. Both China and Russia, I think, if they find a profitable way to use what people call the Iran Trump card, that’s not Trump, it’s capital T, is selling out Iran in order to get something.

Right now, they’re very afraid. A lot of people in Iran are afraid that with Putin and Trump talking that on the table is the Iran card. Americans may say, “If you let go of Iran, don’t support it. We will let you have Ukraine.” That’s always a suspicion they have. That’s probably why Lavrov traveled to Tehran last week to assure them that’s not the case. I would say this fear that Iran is becoming like North Korea, a client state very close to another big power, it’s misunderstanding Iran. Iran is a fairly pluralistic country with multiple interests, multiple views. So far, they have managed to keep a little bit of the neither East nor West slogan that the revolution came with 45 years ago. Y

Talia Baroncelli

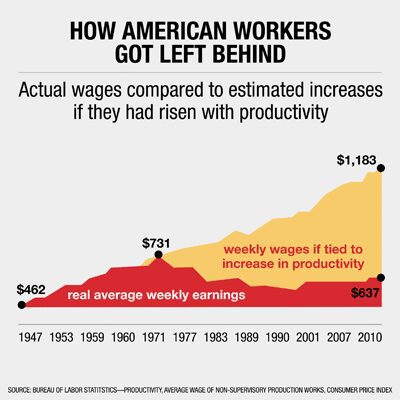

You make a very good point that a lot of Iranians are skeptical of Imperial powers. That’s partly because of the history. I mean, the Imperial Russia, was also involved in looting Iran’s resources over a century ago. So that’s still in their minds, obviously, but it’s also not Russia or China who are sanctioning everyone at the moment. I think there still is a clear understanding of who is the potential, quote unquote, enemy in the sense of who is launching the sanctions which are hollowing out the middle and the working classes, right? Could you explain a bit, at least based on some of the work that you’ve done, how the sanctions are currently hollowing out the middle classes and perhaps impoverishing Iran more, where you have people who maybe were previously more middle class, falling into the working classes?

Djavad Salehi-Isfahani

I don’t want to lose the trail of thought regarding the last question, the last sentence, which is very good, and I want to come back to it, but I thought I’ll make a point that’s useful for this discussion we are having. The point being that Iran’s relations with Imperial Russia and maybe Colonial Great Britain and so on is different from the relations Iran has with the U.S. and sanctions. Iranians all agreed that losing part of the caucuses to the Tsarist regime was bad. They blamed the Iranian government– some of them– they blame the Iranian government for having lost that territory. Colonial powers in general, the way they hurt Iran was visible to everybody. They would be inside the country with their guns, throwing their weight around. We’re talking about Great Britain, south of Iran.

Now, the U.S. hasn’t done that. What the U.S. has done with sanctions is what we call in the book, the invisible war. The invisible war is also invisible to a lot of Iranians, which allows people to think that maybe America is not at fault. Maybe the Iranian government is at fault for being belligerent and not agreeing to things. That is a fundamental change in the anticolonial experience. When the colonial power comes with obvious offensive measures and people rally behind the government– I’m thinking of Algeria, Vietnam, and so on. In the case of sanctions, because they are like a Cold War, people can disagree whether the U.S. is justified or not justified, which is why Iranians are divided on whose fault it is. You see people come, protest in Iran, and blaming their own government. The slogans being, “Give up on Gaza. Give up on Lebanon. My life sacrifice for Iran.” The slogan that has been coming up every time there’s big protests.

I explain that by the fact that sanctions are an invisible war. The government has difficult time rallying people around the so-called flag. Iranians are not strangers to austerity, which is now hitting everyone, almost everyone in Iran. They fought the war. It was very austere times during the war with Iraq in the 1980s. Then there was a [inaudible 00:28:07] structure adjustment. There was, again, austerity, prices rising, 50% inflation, and lack of jobs. They tolerated that at the time because they saw Saddam was the culprit in the war. Then they saw the logic behind moving back towards markets from the coupon system, rationing system during the war. They tolerated the loss of living standards much better than now. Sanctions had their own media support being that its your government that’s causing the problem. It’s not sanctions, it is mismanagement, it’s corruption, which we show in the book that that’s not really true.

Talia Baroncelli

No. I mean, you’re making a good point about Imperialism and the different forms of Imperialism as well. But you’re also– my question was about the hollowing out of middle classes. I guess that’s perhaps one reason why during the protests in Iran, the Mahsa Jina Amini’s protests for women like freedom, that maybe there weren’t so many people from all aspects of society taking part because if people are so affected by sanctions, and there’s this hollowing out of the middle class and people are becoming more impoverished, then they can’t just give up everything to go out on the streets and protest the regime. They’re not able to organize to the same degree as they perhaps would be if they had more economic prosperity or better living standards. So the sanctions have perhaps impacted the middle classes and working classes in that way.

Djavad Salehi-Isfahani

Well, they definitely have impacted all classes. My concern about the middle class that I’ve written before and it was also in the book is because of the particular role they have. Everybody knows that the real suffering is with the poor because they have nowhere to go, lower. The middle class can fall to lower middle class. They can cut back on the food consumption, on the vacations, and so on, and keep their daughter still in school. But if you’re very poor, you lose your job, and you can’t buy food, then sending your daughter to wash clothes in the neighborhood and so on might seem like a very good option than letting her go to secondary school.

With that point made that the real suffering is with the poor, the middle class suffering has a particular cost in terms of long term social and political growth. The poor look to the middle class to strive to make their lives better. The middle class, where countries have prospered, has also looked back at the poor and tried to level the playing field and level the path for them to become middle class, like electing governments in Europe that vote for social protection. It’s the middle class that champions the cause of the poor that becomes legislation that creates a social democracy that a lot of Europeans are proud of.

Unfortunately, in Iran, that hasn’t happened. First of all, the middle class is weaker. We know at least 5 to 6 million, maybe 10 million who were middle class by income measures are no longer middle class. By every other measure, they’re still middle class. The way they treat their kids, schooling of their kids, and lifestyle and so on. They are middle class, but they have become very weak, and they are more concerned with, for example, buying enough dollars, putting it away so that when their son or daughter reaches college age, they can go abroad for schooling or for a master’s degree and so on. For them, the calculation is very complex about regime change versus taking care of themselves.

The Iranian government is very good with protecting the poor, relatively speaking. They have one of the most effective cash transfer programs. That’s off and on. It came in 2010 under Ahmadinejad who was a populist. He tried to use the savings from increase in the price of energy and bread to give as cash to the people. They set up a system that continues to this day, although the money that was allocated at the time has become really nothing because prices have gone up by 20, 30 times. The Raisi government added to that cash transfer. He removed the subsidy for food through the concessionary, a subsidized exchange rate. He used that savings to increase cash transfers, but those are now three years old and have lost two-thirds of their value. Essentially, the Iranian government has the electronic address of every person in Iran and can deposit money in their accounts to make sure they can buy bread, which is still very cheap in Iran relative to the neighborhood. So I would say the poor are easier taken care of than the middle class.

The way I describe the middle class and their aspirations is not where the Iranian government is good at. Provide hope for the young people so they study hard, they want to go to college, they want to form families, they want to stay in Iran. Sometimes I feel like the Iranian government doesn’t like the middle class because the middle class has demands on the government, like social freedoms, political freedoms, that the government is unable to provide.

You hear in Iran that if you don’t like it here, leave the country. That is a very bad way of trying to encourage a section of society that in every historical experience is the engine of growth, are the people who invest, are the people who demand services from the government, and are the people who help the poor join them in a generation or so. So that’s what I can say about the way sanctions have created divisions within the society. The poor feeling that the government can take care of them, although not all of them are being taken care of, but the middle class feeling like this government is not for them.

I think the last round of elections, we saw a little bit of movement in that direction. I would say the election of Pezeshkian who is probably the best representative of a pious middle class in Iran. He’s sophisticated, he’s a surgeon, he believes in individual freedoms, but he also understands that the Islamic Republic is in a very difficult geopolitical situation. I know he’s not doing too well with the promises he made, but he’s the best hope for the middle class at present. Much better than Ahmadinejad, who is also a middle class type of a representative, a populist, because Pezeshkian understands the value of education and understands that a middle class family primarily is interested in having a good future for their children. He knows, just to go back to sanctions, that without some sanctions relief, some access to global markets, that dream of the middle class cannot be fulfilled. Now, I’m happy to go into that a little bit more because I discuss in the book or we discuss in the book, there are two kinds of sanctions, sanctions on oil and sanctions on financial exchange that have different effects on the middle class.

Talia Baroncelli

That was part one of my discussion with economist Djavad Salehi-Isfahani. Make sure you look out for part two. See you next time.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | TuneIn | Deezer | RSS

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter

Djavad Salehi-Isfahani is a professor of economics at Virginia Tech, and a visiting fellow at the Middle East Youth Initiative at the Wolfensohn Center for Development housed in the Global Economy and Development program at the Brookings Institution.