On Reality Asserts Itself, Chris Hedges tells Paul Jay about his criticism of the Iraq War and the events that led to him leaving the New York Times – “great reporters care about truth more than they do about news”. This episode was produced on July 17, 2013.

TRANSCRIPT

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay in Baltimore.

Welcome to part two of our series of interviews with Chris Hedges on our new show, Reality Asserts Itself.

Chris is a Pulitzer prize-winning journalist, a senior fellow at the Nation Institute. He spent nearly two decades as a foreign correspondent in Central America, the Middle East, Africa, and the Balkans. He’s reported for more than 50 countries for The Christian Science Monitor, National Public Radio, The New York Times, for which he was a foreign correspondent for 15 years. You can read more of Chris’s biography now below this video player here. And we’re going to go right to Chris.

Thanks for joining us again.

So pick up the story at this Rockford College speech. Now, just to remind people that don’t know the story, Chris made a speech critiquing the Iraq War which led to him and New York Times going in their own directions, in different directions. As you’re about to make this speech, do you realize, one, how controversial it’s going to be at the moment of making the speech, and do you realize you’re going to have this big fight that results in you leaving The Times?

CHRIS HEDGES, JOURNALIST AND WRITER: No, and yet I had spent my career as a foreign correspondent. And Sydney Schanberg, who worked for many years for The Times, was eventually pushed out of the paper as the metro editor for taking on the developers, who were friends with the publisher and who were driving the working and the middle class out of Manhattan (so now Manhattan’s become the playground of hedge fund managers primarily), says correctly that your freedom as a reporter is constricted in direct proportion to your distance from the centers of power. So if you’re reporting from Latin America or Gaza or the Middle East as I was, or the Balkans, you have a kind of range that is denied to you once you come back into New York and into Washington. So, for instance, I could go on National Public Radio and offer a very frank critique about Slobodan Milosevic and what he was doing in Bosnia, what the Serbs were doing in Bosnia. But to come back to the United States and be that candid about George W. Bush was to get me in deep trouble.

And yet, having spent seven years in the Middle East, having been the Middle East bureau chief for The New York Times, an Arabic speaker, months of my life in Iraq, I understood, like most Arabists, that the invasion of Iraq was based on a fantasy, the idea that we would be greeted as liberators, that democracy would be implanted in Baghdad and emanate outwards across the Middle East, that the oil revenues would pay for reconstruction. All of this was absurd, and all the Arabists knew it. They knew it in the State Department. They knew it in the Pentagon. They knew it in the CIA. And certainly those reporters who had spent time in the Middle East knew it. And yet to speak out was a career killer.

And yet I knew, as subsequently happened, that people I cared about would die in Iraq and other places because of this policy, and I felt that I had a kind of moral imperative to speak, even at the expense of my career. When I went to Rockford College, I knew nothing about the college except that Jane Addams, a socialist and a pacifist who had been booed off the stage of Carnegie Hall for denouncing World War I, had been a graduate. I did not know that subsequently the trustees had tried to posthumously revoke her diploma. And so I spoke as I had been speaking about the war. It engendered a very negative response.

JAY: Paint a picture of where you’re at, who’s there.

HEDGES: It was the commencement address, and I think they thought they were going to get the “follow your dreams” speech, which is what every commencement speaker is hired to give but I was not prepared to give. And so it was 1,000 people. I began my speech. People started booing and hissing. My microphone was cut twice. At one point the crowd got up and began singing “God Bless America”.

JAY: But where is Rockford College?

HEDGES: Rockford, Illinois.

And then two young men in robes from the graduating class got up and tried to push me away from the podium. I had to cut my speech short. The security came and removed me from the podium before the awarding of diplomas. I remember getting down. I had an academic gown on. And I said, well, my jacket’s in the president’s office, and they said, we’ll mail it to you. They took me to my hotel, watched me pack my bags, and put me on a bus to Chicago.

JAY: Why did they invite you?

HEDGES: I don’t know. Because I–.

JAY: Did they not read your columns?

HEDGES: Well, you know, I think they thought that most commencement speakers bend to the occasion and give the usual soporific, boring, and instantly forgettable commencement address. And I just wasn’t interested in playing that game. I did tell them–I remember at breakfast that I was going to speak about the Iraq–. I don’t think any of us knew. They probably didn’t know how frank I was going to be. I think there was–I think we were all sort of clueless as to the reaction.

JAY: Yeah, you must have been surprised yourself at students reacting this way.

HEDGES: Well, sure. It was very hostile and frightening. I mean, when you have a thousand people who really don’t like you, I’m not going to pretend it’s easy.

JAY: This is 2003.

HEDGES: Two thousand and three.

JAY: So there is a big antiwar movement all around the world.

HEDGES: Right. But you have to remember that in 2003 it was “mission accomplished”. We were celebrating the fall of Baghdad. People were reveling in the power and virtues of the American empire. And it was very lonely for those of us who were speaking out against the war. There were very few voices. We’ve rewritten that history pretty well. But there weren’t a lot of voices.

JAY: Yeah, the big protests are before the invasion.

HEDGES: Yeah. And the general public is deeply sympathetic to the war effort, and most of the intellectual class are either silent or complicit.

JAY: So what goes through your mind as you decide to make this speech? You must have had some sense in that postinvasion period that this was going to be controversial and The Times may not like this.

HEDGES: Yeah, I’d been booed, and–well, because my career was never the point. I mean, you don’t volunteer to go to Sarajevo if you’re a careerist. I mean, you can get killed. I mean, I was never trying to build a career. That isn’t why I was a journalist [incompr.] again sort of makes you an anathema at a place like The New York Times, where for most people it’s all about the career. So I didn’t care about my career. I didn’t take those [crosstalk]

JAY: So it wasn’t a big decision. This was the next thing you were going to do.

HEDGES: Well, I didn’t know I was going to part ways with The Times. But at the same time, I wasn’t about to be silent. I was certainly willing to accept whatever costs came with speaking what I thought was the truth. And those costs did come, because what happened was that you got the home movie footage that was picked up by Fox and all these right-wing trash talk cable shows, and they loop them. You know, they run them every hour. They pull out a little bit with the, you know, loudest parts of the boos. And that pressured The Times to respond.

And so the way The Times responded was to call me in and give me a formal written reprimand for impugning the impartiality of The New York Times and that I was guild, your union. So the process is you give the employee the reprimand in written form, and then the next time they violate, under guild rules you can fire them. So it was clear that we were headed for a collision. Either I muzzled myself to pay fealty to my career, which on a personal sense would be to betray my father, or I spoke out and realized that my relationship with my employer was terminal. And so at that point I left before they got rid of me. But I knew that, you know, I wasn’t going to be able to stay.

JAY: This decision that it was never about career, as we said in part one–and if you haven’t watched part one, you really should watch part one and then watch part two–was in the beginning you were a religious man, and this self-sacrifice had religious roots and religious grammar to it. Did it still at this time?

HEDGES: Yeah, and it still does today. I mean, you can’t grow up as I grew up, in the church, you can’t graduate from divinity school as I did and not have that way of looking at the world and looking at your role in the world deeply ingrained within you. I have great problems with institutional religion, but the religious impulse, the moral imperative is something that I hold fast to, and that I think comes out of my roots.

JAY: So which leads you to not compromise with The Times.

HEDGES: Right. Or anyone else.

JAY: So what happens? You realize this is going to part ways. So what happens?

HEDGES: Well, I had written a book called War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning, which I was pretty certain no one was ever going to read, especially with a title like that. And I was cooked. I wasn’t going to get a job anywhere in journalism in American journalism.

JAY: You were already out of The Times then.

HEDGES: Yeah, when I left. So I thought I was going to teach high school and coach track. I used to be a runner in college.

JAY: Did you actually get fired by The Times? Or you decide to leave ’cause you’re–.

HEDGES: No, I left to go to the Nation Institute because I didn’t stop speaking out against the war. And so it was only a matter of time. Now, with the written reprimand, it was clear that the next time there was a blowup, they could get rid of me. And so I wasn’t going to wait. I mean, I was going to be proactive. I was going to arrange for a transition to get out before I was fired, but it was clear that I was going to be fired.

JAY: Now, this has got to be a big cut in pay.

HEDGES: Yeah, you know, what–the irony is that–.

JAY: You’ve got kids.

HEDGES: Yeah, that–well, the big thing was the pension, you know, and medical. I lose medical, I lose pension. But my book sold–War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning sold 300,000 copies. So it was on the basis of that that I could–I didn’t get much of an advance for that, but on the basis of those sales, I then could get a substantial advance to keep writing. And I really didn’t take a deep economic hit at all, because I was able and I’ve been largely now over the last decade to sustain those book sales enough that I can live on it and I can do another book. I’ve not sold–no book I’ve written has sold 300,000 copies, but they’ve sold significantly. But I didn’t foresee that at the time. I didn’t know what I was going to do.

JAY: So what do you make of–I guess, The New York Times charge against you would have been that you’ve crossed the line from journalism to activism. They’re accusing Glenn Greenwald of that with his coverage of Snowden. And, of course, at The Real News we get that often enough. What do you make of that whole line of argument?

HEDGES: Well, let’s–I mean, let’s look at what I was being reprimanded for. I was being reprimanded for challenging a non-reality-based belief system perpetuated by the Bush administration, and in particular figures like Dick Cheney and Richard Perle and Paul Wolfowitz who don’t know anything about the instrument of war, which I happen to know very well, or about the Middle East.

I was speaking out of a body of experience. I was speaking out of a cultural understanding, a political understanding, a religious understanding that they didn’t have. And this wasn’t a political opinion. This was based on years of experience in the region, and in particular in Iraq. But it was a counter-narrative that challenged a narrative that was complete fiction. And so what I was being reprimanded for, if you really want to boil it down to its simplest element, was for speaking a truth that was at that moment unpalatable.

JAY: I was going to mention at that moment, ’cause is there also not something specific about that moment? It’s just it’s not that long after 9/11. It’s just after the invasion. And it’s at these moments the American media, which under–in other moments might have actually maybe not have made such an issue of what you said–they collapse, they cave that these moments as much as they did during the house of Un-American Activities Committee.

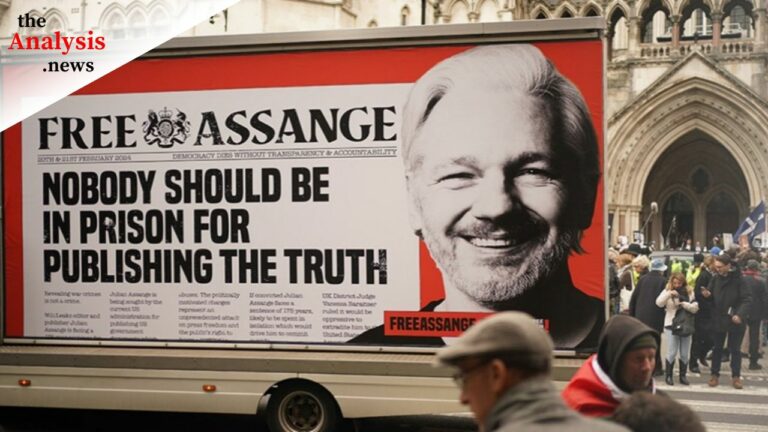

HEDGES: Yeah, but they’ve also caved on Bradley Manning and Snowden and Julian Assange and WikiLeaks. I mean, and I think the media, the American media at its best, which is, you know, institutions like The New York Times had become anemic, and at its worst, which is the commercial airwaves, have just become tools of corporate propaganda. And there’s a crisis within the media establishment that is very, very profound and very frightening.

JAY: And is there also something about The New York Times, The Washington Post, pretty much most, if not all, the mainstream media that there are certain things that are systemically threatening? They usually use the label national security to talk about those things. But when we’re in that area, that’s where they will really intervene editorially. And even if you have done what you said earlier–you’re fact-based, what you’re doing is refuting a mythology–but this has just gotten too sensitive, you could say, for the class interests of the people that are running these newspapers and their relationship to the state.

HEDGES: Yes. And I think that The New York Times–to illustrate the point that you’ve made, of course you have to go back and look at The New York Times coverage in the leadup to the war in Iraq, where they were fed bogus material by the Bush administration and printed it as fact. And then the administration would cite New York Times stories to bolster their case for war in Iraq in this kind of circular mendacity that was taking place between Washington and the part power elite at The Times.

And I was covering al-Qaeda out of Paris and working with French intelligence, who were going insane over this plan to invade Iraq, which–of course they knew the Iraqis had nothing to do with 9/11. And I would come back and meet with the investigative team at the paper and express to them what French intelligence was saying, and they would just dismiss it. I remember there was a kind of racism towards the French at the time, jokes about French culture and French identity. I mean, I heard them even in the newsroom of The Times.

So it was a kind of sickness. Nationalism is a disease. It really is about self-exaltation. And the flipside of nationalism is always racism. And we were self-exalting racists. And I’ve seen it in war after war, from the Falklands to Serbia to anywhere else. You drink that very dark elixir and you become insane. And we became insane, because, you know, I was in the Middle East right after 9/11, and the Muslim world was appalled at what had been done in their name, these crimes against humanity that had been committed on American soil.

And the way you fight terrorism is to isolate terrorists within their own society. And this goes all the way back to Sallust writing about the Jugurthine wars. It’s not a new understanding. And we had gone a long way to doing that because of the attacks of 9/11. And if we had had the courage to be vulnerable, if we had built on that empathy that was being poured out towards us, we’d be far more secure and safe than we are today.

Instead, we responded just the way al-Qaeda and these groups wanted, which was to invade and begin dropping iron fragmentation bombs all over the Middle East, which resurrected the jihadist movement.

JAY: And just to get back to The Times, The Times has the credibility to do this kind of stuff up to the war in Iraq because they do allow a fair amount of fact-based reporting that actually is legitimate. So you kind of believe what The Times says.

HEDGES: Right. Well, every article they wrote which was a lie about weapons of mass destruction, you know, being part of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq was technically fact-based. It was sourced, you know, senior intelligence officials say. I mean, it was double-checked with other intelligence officials. It was all within the rubric of American journalism, legitimate journalism. It just happened to be a lie.

JAY: And one could note, many people did know at the time.

HEDGES: Well, but those people we never spoke to, whether they were the French, whether–.

JAY: That’s my point. You can construct the verifiable stream, but you don’t talk to the people that threaten what you will say.

HEDGES: Right. And that is the difference between news and truth. And I think the really great reporters care about truth more than they do about news. They’re not the same thing.

Remember, as journalists, our job is to manipulate facts. I did it for many years. I can take any set of facts and spin you a story anyway you want. And if I’m very cynical, I can spin it in a way that I know is good for my career but is not particularly truthful to my reader. And I always attempted to convey to my reader the truth.

But reporters who keep hammering home the truth often become management problems and they don’t rise within the organization. You know within the institution what will advance you and what will not, and, you know, you don’t need a list of rules written on a wall so that the hierarchy of an institution like The New York Times is dominated by people who are careerists, whose loyalty is to their own advancement rather than to the truth. And yet all great journalistic institutions need those reporters who care about truth–David Cay Johnston, you know, Sydney Schanberg, who I mentioned before. I mean, they were there. What happens is that they often eventually have a confrontation with that institution. And because they have that kind of integrity, they’re often cast–usually cast aside by the institution.

JAY: Okay. In the next segment of our interview with Chris, we’re going to start the discussion about what should be done, and we’re going to talk a little bit about Christian anarchism and some of Chris’s philosophical beliefs. Please join us for this next segment of our interview with Chris Hedges on The Real News Network.