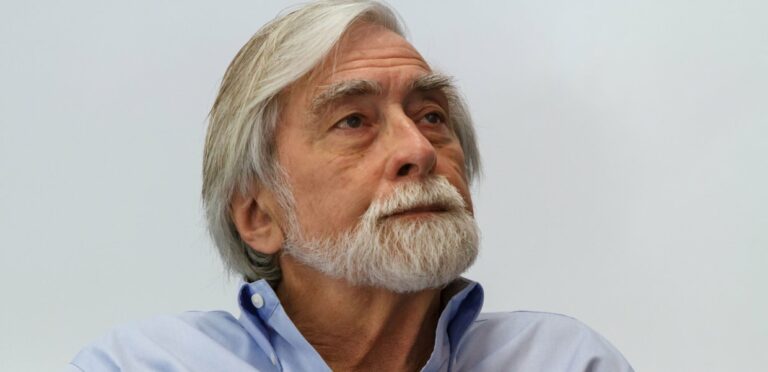

Bill Ayers tells Paul Jay the Weathermen were delusional about armed struggle because they mistakenly thought the American people were in a revolutionary crisis during the Vietnam War. This is an episode of Reality Asserts Itself, produced November 8, 2016, with Paul Jay.

STORY TRANSCRIPT

PAUL JAY, TRNN: Welcome back to Reality Asserts Itself on the Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay and we’re continuing our discussion with Bill Ayers. Bill joins us again in the studio. Thanks for joining us. BILL

AYERS: Thank you Paul.

JAY: And just to remind everybody. Bill is a social justice and education activist based in Chicago. For his whole biography, you can look down below the video player. You should watch part 1 where we do the whole biography. So let’s continue. So we were talking about what happened in terms of the internal fight within SDS and the birth of the Weathermen.

AYERS: What I’m pointing to is the fact that it wasn’t just a matter of our nievaty or our various kind of orientations or experiences that created some of the tensions in SDS. The real tension was caused by the fact that we had mobilized primarily around the war in Vietnam and we thought we had won by 1968, that the war would end as the President of the University of Michigan predicted it would, as we all thought it would when Lyndon Johnson stepped aside. But then it didn’t end. It escalated. That created a crisis.

JAY: With Nixon as president.

AYERS: With Nixon as president. And with Henry Kissinger as his Vice [inaud.]. So here was the situation. I’m the middle, as I said, of 5 children. Within my own family, we split into different ideas on what to do. One of my brothers joined the democratic party and tried to build a peace wing within it. One of my brothers went to Canada with the great migration and organized a home for deserters in Vancouver. One went to work in the steel mills to organize the industrial working class. One went to the communes. And I did what I did which is to be part of forming an underground armed struggle organization. Our idea was that all these choices were being made because of what we couldn’t end the war and people were thrusting about trying to figure out what do we do? How do we do it? This mirrored the society as a whole. But here was the situation. The situation was that every week that the war went on, 6,000 people would be murdered. Every week. And there was no end in sight. We can now look at it and say it was 10 years 3 million people were needlessly thrown into the furnace of war. We can say that now. But in 1968, all you could say for sure was that a million people are dead and 6,000 people a week are being killed. What do you do? How do you live your life in a way that it doesn’t make a mockery of your values? None of us knew. But we went our way.

JAY: So there’s obviously an enormous debate over armed struggle versus mass organizing.

AYERS: That was one struggle. But there were struggles as long as I was in SDS. I joined in 64. There were struggles. So, struggles about national demonstrations versus local demonstrations. Struggles about how much to put the African American freedom struggle in the center of things. How much to organize around student power? These were arguments that went on forever. They’re not wrong. These are arguments we should have and debates we should have. On the question of armed struggle there was of course a fierce discussion and debate within ourselves and I’ve written a lot about it in terms of trying to make sense of it for myself.

JAY: Here’s a quote from Chomsky about this whole period. I’m sure you’ve heard this quote before: “Weather Underground didn’t think through what they were doing. I spent a lot of time trying to convince young people not to join the Weather Underground. I mean, you can argue about whether the Catholic Left had the right tactics or not, but the Weather Underground was, I think, no justification for their tactical choices. I mean, you can understand their mood, there was a mood of real desperation, especially among young people feeling like we’ve tried everything, nothing’s worked, we’ve got to go all out. The actions were completely counterproductive for themselves, for their effect on others. Remember, such actions are, and a lot of ’em really thought they were bringing about a revolution. They were living in a delusional world. The U.S. was not in a state where it was going to be a revolution. They were living in a completely delusional world, of a kind that teenagers might live in, very desperate, very angry, and picked tactics that were harmful, and caused themselves lots of harm as well”. What do you make of that? You were living in a delusional world and that it did no good.

AYERS: Probably so and saying we were like teenagers. We were teenagers so that makes sense. Yea there was a certain amount of delusion and I would say that the main delusion was we thought that the American people were in a revolutionary crisis with the American government and that turned out not to be true. There was a lot that was powerful for all of us and not just the Weather Underground about believing that we could bring about a radical change that we actually thought it was on the agenda. That gave us a confidence that is necessary to reignite. I think that you have to believe that another world is possible and see it somewhere hazily on the horizon. In order to act in order to take risks. I disagree with some of what Noam Chomsky says there. But I admire him so much and he’s said so many things and many of us have been friends with Noam for many many years. It doesn’t either surprise me or dishearten me completely.

JAY: But you must’ve heard arguments like that at the time?

AYERS: Oh yea, the one thing Noam doesn’t say and that other people have said is that not only were we counter productive to ourselves but somehow that we damaged the anti-war movement. I in many ways reject that. We were part of the anti-war movement. So much a part of the anti-war movement that we were protected for 11 years I was underground. No one ever saw fit to turn me in. Even though I was recognized on the street consistently over those 11 years. People I worked in places where I ran into old SDS people. Nobody ever said that, ‘you should be in jail’.

JAY: I guess the argument for what would’ve been counterproductive would be one in terms of winning over more American public opinion. It kind of played into the hands of the pro-war forces.

AYERS: I don’t buy it. I’ll tell you why I don’t buy it. Because I don’t think anybody at that point when the war was so exposed, so naked in front of us and so many people had moved against it. Let me back up for one second because the reason people moved against it wasn’t just the anti-war movement. In fact I don’t think that was the primary energy that moved people against the war. The people moved against the war because the Vietnamese had a just and righteous struggle and they were winning on the battlefield. Three things happened in this country. I mentioned anti0war organizing. What I didn’t mention was that the black movement moved not unanimously but forcefully against the war. That really undid a whole lot.

JAY: But all that can be true and still those tactics could be counterproductive.

AYERS: It could be but what I’m saying is-

JAY: Like imagine today if, and there’s even some signs but you can see what happened if some organized black militant group went around assassinating or blowing up police stations. I know you weren’t trying to kill people.

AYERS: Without speculating on that I mentioned the black movement only to say that there was a social force in the United States that opposed the war.

JAY: I’m just saying you could see how it could be counterproductive in playing the hands of now they can go out and arrest all the leaders of black lives matter.

AYERS: It could be but in the couple of places where things have happened with justifiable rage on the part of undoubtedly people who were in some ways delusional. But the justifiable rage has not actually set the black lives matter movement back at all. In fact they’ve been very sophisticated.

JAY: You’re talking about the shootings of cops that have happened?

AYERS: Yea in Dallas for example. It didn’t actually.

JAY: Yea because it was clearly not an organized movement but you guys were.

AYERS: No I don’t agree. You’d have to show me. First of all I think it’s very very difficult to make a causal claim about what the anti-war movement did and what the Weather Underground did and say this caused that. It’s very hard to do that.

JAY: I’ll give you one more argument I’ve heard people make which is not that COINTELPRO needed – there would have been a COINTELPRO with or without the Weathermen because they were trying to get rid of the whole leadership of a generation. Particularly black leadership. But others as well. But it did help justify COINTELPRO.

AYERS: To somebody. But not to you and not to me and not to most people. I don’t think so. I actually don’t think so. You’d have to show me. As I say I think causal claims are a little bit sketchy at this point. Partly because it all happened a minute ago. I’m reminded of [inaud.] when he was asked by a French journalist at the end of World War 2 what the impact of the French Revolution of the 18th century was on the Chinese Revolution of the 20th century and [inaud.] said too soon to tell. So, I think we do a lot of crazy.

JAY: I’m not so sure. Looking at the way China’s going I don’t know if it’s so doomed to fail.

AYERS: What I’m saying is that I think that these things whatever the 60’s was and incidentally I reject the idea that there is anything called the 60’s except a myth and a symbol. But whatever it was, it was prelude to what’s happening now. It wasn’t a thing in itself. Nobody looked at their watch in 1969 and said it’s almost over.

JAY: Was there anything positively achieved over the tactics of blowing things up?

AYERS: I think so.

JAY: What?

AYERS: I’ll tell you but you’d have to show me. I was starting to say, you’d have to show me somebody saying you know I was against the war and the Weathermen put a bomb in the Pentagon and now I’m for the war. Just never happened. It’s a preposterous idea.

JAY: I’ll give you an example okay? A current example. Which is somewhat similar. During the Toronto G20 when there were large protests, 20-25 thousand people on the streets against the G20 neoliberal economics and all this. I would bet, I can’t prove it but there would’ve been widespread sympathy for unemployment and free trade that didn’t work and so on. What happens is and partly through police infiltration, partly through their own agenda, black block tactics break off in the main demonstration and several police cars get caught on fire. I think most people think those cars were left there deliberately so they would be lit on fire. Whether a provocateur did it or whether someone spontaneously did it, the only image on television from that point on is a burning police car, which becomes the justification for mass arrests. They arrest a thousand people. They beat the hell out of everybody in sight. They ride over people with horses and the public mood after that is all based on well they burnt police cars down, what do they expect?

AYERS: You know, not being tactician, then or now, it’s hard for me to talk tactics with you except to say this, that the way you figure out tactics is never perfect and you do it within the struggle itself. So, the people who do not like what the black block does or what certain people did during Occupy, and some have to go down and be in line and be in the microphone. I mean we learned through struggling. Do we make mistakes on the left? All the time. Every successful revolution has made terrible mistakes. You take South Africa, the anti apartheid movement. The whole purpose of the truth and reconciliation process was partly a process of re-healing the society to some extent. But it was partly a process of the ANC itself. The Revolution itself. Clearing up what it did that was wrong and it did plenty wrong.

JAY: I think it’s any question that the armed struggle in South Africa if there hadn’t been one, there probably would’ve never been an end of apartheid.

AYERS: Exactly and so we-

JAY: But that was a mass struggle more or less.

AYERS: But I’m arguing to you that there was a mass struggle here. For black freedom and against an unpopular war. We had two simple goals in the early 1960’s. One was to end this particular war and one was to end segregation. We failed on both. We failed on both. We did not end segregation. We did not take a deeper course, we did not end white supremacy. But we did end this war and we then wanted to end the basis of war. I get a little uneasy about claims that people make about the 60’s about how great it was and what we accomplished. We accomplished a lot. Part of what we accomplished was we learned to fight by fighting. We learned to struggle by struggling. We tore ourselves away from the scripted lives that we were destined to live. I think that is a victory in itself. But it’s a modest victory and I wouldn’t claim too much for it. But we memorized in great detail, Nelson Mandela’s speech at Rivonia. We knew that argument and we were part of that argument. When Nelson Mandela – I’ll tell you a quick story. When the Weather Underground film was released at Sundance, a film by Bill Siegel and Sam Green, and we were there and we went into the Green room to meet with the press and a lovely reporter from the LA Times said, why couldn’t you have been nonviolent like Gandhi and Nelson Mandela? And Bernice and I, my partner and I said to the reporter, well what was Nelson Mandela in prison for? And the reporter said, well for opposing apartheid. And my partner said, yes opposing apartheid and building an army. Starting an armed struggle. He was tried for treason. Not for sitting in at a lunch counter. And at his treason trial, he stood up and gave this famous speech called the Rivonia speech. And his life was hanging in the balance. He could well have been killed for this speech. But he made a justification for armed struggle and he made a distinction between destruction of property and killing of people. Between armed struggle against machinery and terrorism against people. He made a very strong distinction and he said it may come to that. But we’re not there yet. But we are going to destroy property. And that’s what they set out to do. Did they make mistakes? Lots of mistakes. Did they do stupid things? Yes. But the cause was just and it was part of a mass movement. What I’m arguing to you is the Weather Underground for all of it’s weirdness, the Black Panther Party was part of the movement. We were part of the movement, meaning we weren’t the leaders of the movement or the center of it but we represented a part of the struggle against the war against white supremacy.

JAY: I don’t think too many people would argue against that. But certainly there’s a difference between armed struggle in South Africa which is supported by I would guess a large section of South Africans would have supported that armed struggle. Many many participated, were sympathetic.

AYERS: Yes and a lot of people opposed it.

JAY: I’m sure. I’m sure there’s always this fight. Exactly. But certainly here there was the possibility of igniting any kind of armed struggle with the mass character. I mean did you really think thousands of people were going to join this armed struggle?

AYERS: Yes.

JAY: Then you go back to Chomsky’s delusional goal.

AYERS: They were delusional exactly. And guess who else was delusional? John Brown was delusion when he raided Harpers Ferry. Now we can see that he was delusional. If you or I had been in conversation with Fredrick Douglass and John Brown, I think we might well have joined the struggle at Harpers Ferry. It was delusional. It didn’t work. He was hanged.

JAY: But certainly when you’re at the level of muskets it’s a little bit more reasonable.

AYERS: Yea but the argument was made that he set back the abolitionist cause. Did he? I don’t think so. I think he united the Civil War. You don’t know in advance. You know after the fact and you can say – so my argument isn’t that we were great or brilliant or it was the right thing to do. That’s not my argument. My argument is I have no apologies for that part of what we did. In other words, 6 thousand people a week are being murdered by our government. We’ve done what we were told we must do by ourselves and others. We built a mass movement. We built a majority opinion not just to us. The black movement as I said. Vets coming home, very important. Telling the truth about what they saw. That was a huge energy that turned the country against the war. But now here we had a country against the war and the war couldn’t end. 6 thousand people are being murdered and it’s blatant. It’s obvious. People know it and the anti-war sentiment is growing. Black freedom movement has reached certain goals but the goals deepen. Just like every other struggle, when you win through struggle, when you win reforms, your mind goes to a deeper possibility. When I say Martian Luther King was a radical, what I mean is he was going to the root of things by the end of his life.

JAY: Looking back, I’m not arguing whether it was part of the movement or not. I think most people.

AYERS: I don’t know about most people.

JAY: Anybody who was an activist during that time debated the issue. And it wasn’t so outlandish to talk about it or think about it.

AYERS: It’s hard to believe today but it’s true.

JAY: I mean this is at a time where there’s national liberation movements and you know arm struggles at very high levels around the world.

AYERS: Everywhere. Canada, Europe.

JAY: Looking back, was there anything productive from blowing – you just told me off camera there was maybe 30 thousand bombings during this time. I don’t know what number of that would’ve been directly part of the Weathermen network.

AYERS: A tiny number.

JAY: There was a lot of people who jumped in and did it.

AYERS: Yea and ROTC buildings were burned down and Banks of America were bombed, yea. So it was happening spontaneously.

JAY: I honestly can’t remember. Were people killed in any of that?

AYERS: The one in Madison killed a researcher. The Army Math Building. Terrible, terrible tragedy. Very well-known at the time. Terrible. So yes, people were killed.

JAY: So now looking back, is there anything that was accomplished out of this tactic?

AYERS: I think that

JAY: Chomsky calls it counterproductive. Is there anything productive?

AYERS: I’m not sure. I’m not sure I could say that there was except to say that what the bombings did and they were like the Catholic Left. I mean Chomsky references the Catholic Left too. They were destroying property. They were burning draft files. IT was a form of kind of excessive vandalism against property with a very direct political focus. And did it change hearts and mindsets? I bet it did. I think it did in the sense that people saw that here was not just a small group of people but many people willing to put their lives on the line, having the courage to risk their lives in order to do this madness, this war. What I regret about those days, since I’ve said I don’t really regret the destroying of government property. I don’t regret the destroying of police property in the aftermath of the killing of Fred Hampton or the killing of other African Americans around the country which you have to remember that the black panther panty was founded 50 years ago. Because of police violence. It’s not like this is a brand-new phenomenon. This is the oldest phenomenon in race relations in the country. But what I do regret is a kind of arrogance and self-righteousness. A kind of sense of certainty and dogma. A sense that if you weren’t with us you were against us. And that infected the movement generally. That was a catastrophe. That if I could back and rewrite something, I would still destroy property but I would not destroy friendships and relationships.

JAY: One of the critiques of the tactics and not only the tactic of blowing up building I think reflects itself in other tactics and parts of the movement. And it’s partly people coming from a life of privilege but not only, that their search for their personal significance, their personal feeling of I have to do something to make my life meaningful. Sometimes becomes more important than the objective assessment of whether the tactic’s actually going to be good for the well-being of most people or not.

AYERS: I couldn’t agree with you more in that I think one of the things you learn if you stay with the struggle is that you learn that there’s a simple metric to figuring out tactical questions and simple to state and excruciatingly difficult to enact. But this is what you should be majoring your tactics against. You should say, did I learn? And did I teach? If I learned and I taught, then it was a good thing. If I didn’t learn and I didn’t teach but I looked great on the nightly news, not good enough. So I would argue that but you can’t always know going in and that’s also worth remembering. So, we’ve talked about South Africa, we’ve talked about Black Lives Matter. We’ve talked about the anti-war movement. But you don’t know when you stand up. I would also just quibble slightly with the search for personal meaning is a good thing. Trying to live a purposeful life is a good thing. So let’s take a current example. Colin Kaepernick takes a knee against the Star Spangled Banner. He had no guarantees. He had no sense that there was any social movement involved in that. He did it as an existential act of protest. Look what it’s created. I mean I immediately bought my Colin Kaepernick jersey, I hope you did. I could be wearing it right now. But everywhere you look now, things are popping off in opposition to the Star-Spangled Banner and I’ve tried to be aware of a lot of things. I had no idea that there was even a third stanza to the Star-Spangled Banner until Colin Kaepernick brought it to my attention. Everyone should Google, third stanza Star Spangled Banner. It’s not only a war anthem written by a slave holder. It celebrates the murder of African Americans. It’s a disgusting song. We should never sing it. I’ve always sat my whole adult life but now I’m wearing my Kaepernick jersey when I sit, at the Cubs game for example.

JAY: And I don’t think we should go back just to end this segment and remind everyone again that just about everybody involved in this are essentially teenagers in the early 20’s and number 2 a whole generation of leadership had been wiped out during McCarthyism and the house of unamerican activities committee so many people had been purged that had experience from the 30’s and the 40’s. And the same thing happened with COINTELPRO. It wiped out a whole generation.

AYERS: Without a doubt and it happened with the Phoenix program in Vietnam. There’s always a counterinsurgency against leadership. So, one of the things about us in SDS and in SNICK in the early 1960’s is that we called ourselves the New Left. That was both a great strength and a terrible weakness. The strength was that we were breaking from the hopelessness of the communist party left and we were saying this is new, this is energized and of course it also meant we didn’t have things to learn from the communist of the previous generation. That was mistake.

JAY: Okay please join us for the next part of our series on Reality Asserts Itself with Bill Ayers.