In part two, journalist Jonathan M. Katz discusses the financial elite and fascist sympathizers who were conspiring to undo FDR’s economic reforms in what is known as the foiled Business Plot of 1933. Retired U.S. Marine General Smedley Butler, who outed the coup plotters in Special House committee hearings in 1934, subsequently published War is a Racket, a pamphlet critiquing the monied interests behind America’s imperial war machine. Katz describes Butler’s transformation from “racketeer for capitalism” to anti-war critic and underscores the political salience of working-class issues in the Great Depression’s aftermath, as demonstrated in the Bonus March of 1932 and in FDR’s New Deal.

Gangsters of Capitalism – Jonathan M. Katz Pt. 1/2

Talia Baroncelli

Hi, I’m Talia Baroncelli, and you’re watching theAnalysis.news. This is part two of my discussion with journalist Jonathan M. Katz. In part one, we were speaking about the legacies of U.S. colonialism. If you enjoyed part one, you could go to our website, theAnalysis.news, and if you’re in a position to donate, feel free to hit the donate button at the top right corner of the screen. Make sure you like and subscribe to the show on YouTube or on other podcast streaming services such as Apple or Spotify. Also, make sure you’re on our mailing list; that way, you’re always up to date every time we publish new content. See you in a bit with Jonathan M. Katz.

I’m very excited to be joined by Jonathan M. Katz. He’s a journalist and author of the book The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster. His second book, which we’ll be discussing today, is called Gangsters of Capitalism: Smedley Butler, the Marines, and the Making and Breaking of America’s Empire. So, thanks so much for joining us again, Jonathan. It’s great to have you back.

Jonathan M. Katz

It’s wonderful to be here.

Talia Baroncelli

I have two more broad-stroke questions. My first question would be, what was the role of class at that time? Reading your book, it seems like it was much more important and present in terms of how it was used in politics. So, for example, the assassin of President McKinley was a steelworker, unemployed in 1893 because of the Depression. Then he ended up killing McKinley, also partly in response to maybe some of the images coming out of the Philippines and all the atrocities in 1901. The class element is really present there.

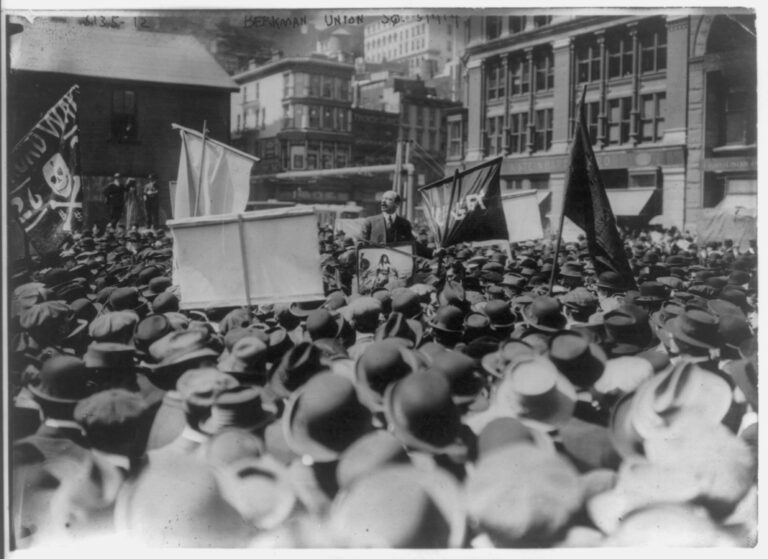

Then also, in the early 1930s, obviously, there was the Great Depression. Then, in 1932, you have the Bonus March on Washington, the bonus expeditionary forces. They were veterans. About 43,000 of them marched onto Washington. They wanted to get their bonuses paid out for having fought in World War I. The Senate was discussing this, but then I think they just ended the session and didn’t want to pay the veterans. Then, there was a huge encampment and protests, and General MacArthur was involved in ordering one of them to be shot, I believe. That also led to FDR becoming President and implementing the New Deal and essentially trying to avert– well, I think what he was trying to do was to avert people becoming Communists. He wanted to ensure that people had access to jobs, full employment, and better conditions so that they wouldn’t turn to Communism.

Why don’t we speak about the role that class played at the time in politics? My final question will be about the coup that Smedley Butler foiled.

Jonathan M. Katz

Yeah. Really briefly, class is extremely important in understanding everything that’s happening here. Butler’s class and his ability to move between classes in some ways, at least in terms of reputation, I think, has a lot to do with his politics and also what he ends up doing and what his reputation ends up being. Like I said, he’s a rich guy. His father was a very powerful congressman throughout Butler’s life. He plays a very important role on the Naval Affairs Committee, for instance. His mother’s family is very rich in banking and the railroads, but he doesn’t go to college, and he’s in the Marine Corps.

The time that he’s in it, it’s very much a working-class activity. It still is in a lot of ways. As he’s in there, there are efforts internally within the Marine Corps to professionalize, especially the Officer Corps. By professionalizing, that almost invariably means bringing in people who are better educated, better spoken, and have time in their lives to sit around reading theory. There become these internal struggles between the working-class Marines and what Butler ends up calling the swivel chair admirals, the people who didn’t fight their way up to the ground. They came in from the academy.

Butler very much takes the side of what he calls the roughnecks. These guys tend to be poorer, they tend to be less educated, and they went into the Marines for a paycheck or because it was one of the only avenues of access that they had to either escape the towns that they grew up in, to get any prestige, or a sense of accomplishment of having been part of a big national project in their lives.

Throughout this period, he’s on the side of the working-class Marine. This ends up, I think, translating to an appreciation of the struggles of the working class in the United States in general. Butler also ends up– when I talked about counterinsurgency and the ways in which he’s able to see the people that he’s dominating as people, but he really does absolutely horrific things. He also is able to see some of the people who he’s dominating or who he’s serving among as people as well. He develops some sympathy, at a minimum, for impoverished Haitians, impoverished Hondurans, Nicaraguans, Filipinos, and things like that. All those things, in a lot of ways, come together for him at the end.

Another big radicalizing moment is World War I. There’s obviously a lot to say about it, but he is based in the rear in World War I. He oversees initially a disembarkation and then an embarkation camp, same camp. He spends a lot of his time trying to care for the needs of the rank-and-file soldiers who are especially coming back to his camp, having gone through the horrors of the trenches and the gas in that war.

All those things, in a lot of ways, come together, as you note in the Bonus March. Very briefly, what happens is it’s the depths of the Great Depression. Servicemen had been promised as a way to sell the draft because there hadn’t been a wartime draft since the Civil War. Woodrow Wilson, the way that he gets men and their families to allow them to submit to the draft is he promises that they could get back pay for the time that they were away from the factory or the fields while they were at war. This is an enormous bill, and Congress keeps putting off any payment for it. Finally, an agreement was made in the ’20s under Calvin Coolidge to pay out the bonus as it’s derisively known because opponents of this compensation, of this backpay, call it a bonus because they’re like, “You had the privilege of going to war and getting blinded by gas for your country, and now you want a bonus?” This becomes the common name for it.

The agreement that’s arrived before the Great Depression is that this will be paid off in 1945 or on the death of the soldier, the veteran, whichever comes first. In 1945, at this point, by the way, nobody knew that it was going to be this extremely significant year in history. Yeah, they’re just like, “1945, that’s far enough in the future. It’s like 1925 or whatever. It’s far enough in the future that we can deal with it in 20 years.” During the Great Depression, poor working-class people, and a lot of people have been thrown into the working class, a lot of people have been thrown out of the working class into the non-working class. Actually, 25% of the planet is a significant portion of the population.

For veterans, the only thing that they have in their lives that has any monetary value attached to it is this bonus certificate that they were issued in the ’20s. So, 10’s of thousands converge on Washington, D.C., and set up a tent camp. We’re getting a little old now, but for those who remember Occupy Wall Street, it was like Occupy D.C. in 1932. They hitchhike, they take trains, they converge on the capital, and they bring their families. They’re there demanding that Congress, the Senate, specifically, pass a bill paying out the bonus immediately. The establishment is very threatening to the administration of Herbert Hoover, who is an old frenemy of Smedley Butler’s. He got Butler shot in battle in China in 1900. You have to read the book to get all the details about this. Butler ends up getting court-martialed by or has already been court-martialed by Hoover for Butler’s insults against Benito Mussolini.

Talia Baroncelli

Yeah, because he said that there’s a case of Mussolini saying that a child was run over by a car. What is one life compared to the great life of the State or something like that? It’s nothing in comparison.

Jonathan M. Katz

Yeah, he spoke out of turn. He told the truth in an opportune moment. So, in this moment, in this bonus camp, it’s an enormous deal of the time. It’s basically an organic movement of just poor, out-of-work veterans, but there are different philosophies and different fringe elements that are trying to take advantage of this. There really is, like, the CPUSA, the Communist Party of the United States; Earl Browder really does send representatives to try to convert and to see if we can do a Communist infiltration of this thing. It doesn’t really work. There’s no evidence that that happened. There’s also a lot of sympathy, especially among some of the organizers of this, toward fascism, one of the organizers in particular. There’s a lot of fear.

As you noted, this ends up being– Butler comes to speak on behalf of the Bonus Marchers. It’s actually after the Senate has gone on vacation without acting on the Bonus Bill. They snuck out through the tunnels under the Capitol because they didn’t want to confront the Bonus Marchers. Butler goes and gives a rousing speech that’s just like, “Don’t leave. Stay here.” He understands organizing, and he also understands the power of location and holding high ground, both physical and moral. He’s like, “Don’t leave. Stay here because as soon as you’re gone, you lose your power.”

Nine days after this, Hoover orders Douglas MacArthur, the Chief of Staff of the Army, to basically invade and destroy the encampment, which he does with the assistance of his assistants, Major Dwight Eisenhower and Major George Patton, among others. It’s this very heightened moment. MacArthur sees that what he’s doing is he claims outright that he has stopped a Communist revolution in its tracks. Effectively, what’s happening at this moment, and this will, I think, lead us to our final destination, what’s happening at this moment in the early 1930s is that there’s a broad agreement across American society, across much of the West, that Liberal democracy has failed.

It’s like the two single accomplishments of Liberal democracy at this moment in this period are World War I and the Great Depression. The idea is clearly that this isn’t working. Some people are looking to the Soviet Union as an example to follow, and other people are looking to fascist Europe, especially Germany and Italy, as an example to follow. A lot of the people who are looking to fascist Europe tend to be Plutocrats. They tend to be the wealthier, the industrialists, and the more business-connected.

Talia Baroncelli

And the bankers, J.P. Morgan.

Jonathan M. Katz

And the bankers, exactly. They’re like, “Okay.” For a while– I’m not doing it justice here, but like, socialism has arrived and it has won a revolution. The Communists have won a revolution in Russia in 1917. People start looking at this and other class-leveling theories, including anarchism and proudhonism. There are other things that are in the conversation at the time, but there are a lot of people in the U.S., in particular, who are looking, and they’re like, “Look, this is the alternative that speaks to us.”

Then fascism comes around, basically as a direct response to socialism. Mussolini is an ex-socialist. Effectively, what Mussolini’s innovation is, if you can call it that, is it’s a way of reorganizing society in the sense that it is not a monarchy, although Italy still has a King. It’s not a Liberal democracy at all, obviously, but it’s also not Communist. Mussolini incorporates all of these ideas that are ways to defang and outmaneuver socialism by, for instance, creating what he calls corporatism. The term is often misunderstood, but what Mussolini means by it is essentially creating national workers’ guilds that involve both capital and labor. It’s a national labor union, kind of, but instead of having a labor union, you have a corporation, corporazione, which has the heads of the steel mills and the workers of all the steel mills together in one steel corporation. That’s just one example. There are others.

The other thing that his black shirts do, his street toughs, is they just go bash in the heads of labor organizers and Communists. Obviously, it imprisons people like Gramsci, who wrote his prison notebooks because of this. It’s basically like, from the perspective of people who want to keep their money and their class and their power in the United States, they look to Mussolini in particular as being this great modernizer who has found the solution to both Liberal democracy and Communism. Obviously, the Bonus March does not end up becoming either a Communist or a fascist revolution.

What happened is Franklin Eleanor Roosevelt, who was another friend of Smedley Butler. They hung out together in Haiti because Roosevelt helped oversee the occupation of Haiti as Assistant Secretary of the Navy. Roosevelt is in some way similar to Butler, obviously a little different, kind, and tender, but he’s a class traitor in some ways. He’s a very rich guy with a very powerful family. Very wealthy. The Roosevelt’s are both politically and economically powerful in New York. He’s the governor of New York at this time as he’s preparing to run for president. He looks at what happened in Washington in 1932, and he’s horrified. He sees both the brutality of MacArthur. He sees the imposition of fascist Mussolini-like tactics against American citizens. He also sees the threat. He shares Hoover’s fear of the threat of a Communist revolution in the United States. He’s like, “We need to do something about this.” His run around all of those ends up being effectively the New Deal.

His theory is, and I think it works, is let’s show people that a Liberal democracy can meet their needs. We will use the power of the state, we will use the wealth of the state, and we will use the collective wealth of the American people that we control through tax revenues to show that we can work in the interests of the working class. We can put people back to work, we can put the Plutocrats in check, we can raise taxes on the rich, and we can get money off the gold standard, which is something that the American working class had been demanding for decades at this point, well into the late 19th century.

There’s a whole suit of things: rural electrification, ultimately, social security, and all these different things. What he’s doing there with the New Deal, this is the purpose, really, of the New Deal– Eric Rauchway is a historian. He’s written about this at length. The real purpose of the New Deal is to show Americans that you can participate in a government organized under the U.S. Constitution in which you vote for leaders who will accomplish your ends, who will help you, and will help you in a lot of ways on a class basis against the wealthy.

Wealthy Americans are scandalized by this because they don’t understand what Roosevelt was doing. They don’t understand that Roosevelt is trying to short-circuit, effectively, Communism or any push toward socialism in the United States with social democracy. As they see it, he’s just a socialist. He’s effectively just a Bolshevik, and he’s going to turn the United States into the Soviet Union, which is ridiculous. It’s not what Roosevelt was trying to do, as Communists at the time would have very gladly told you. They don’t see it that way, and so they say, “Okay, well, if just reading Mussolini doesn’t work, we need to do what Mussolini did, and we need to stage effectively a March on Rome in Washington.”

They recruit a middleman named Gerald C. MacGuire. Jerry MacGuire, goes to recruit Butler in 1933 and 1934, using the bonus and his experience in the Bonus March as a wedge to basically try to denounce Roosevelt at the American Legion, which is a very reactionary force at the time. The American Legion, by the way, was inviting Mussolini to their conferences. This is not theoretical. In 1934, MacGuire started sending Butler a series of postcards from Europe. He visits fascist Italy. He visits Berlin, where Hitler has recently come to power, and is very fond of both of them, but he doesn’t think those models are going to work in the United States.

The model that he decides to adopt is a model that is being tried out in France, a country that, in a lot of ways, politically, has a lot more in common with the U.S. It has a much longer history of being a Liberal democracy. It hasn’t been a monarchy as recently as Germany and Italy both have been. On February 6, 1934, there was a far-right fascist riot, which involved one small group of revolutionary Communists because they always had to be there to basically storm the French legislature and prevent a transfer of power to a center-left government.

This is driven by anti-Semitism, it’s driven by conspiracy theories, and it is just generally driven by the fear in the French Right, as it is in the U.S., that this center-left government, which is the most milked out center-left government, but that they’re just going to be a stalking horse for Communism. That Communism is now going to come to France. They storm the French legislature. They get into a huge fight with the police. There are a lot of parallels between January 6 and February 6, beyond even the day of the month. The riot is a clown show. They don’t even reach the Palais Bourbon, which is where the French legislature sits, but they are able to intimidate the center-left government into not taking power. So, instead, a center-right government comes to power.

This is a very important event in France. It really, in a lot of ways, sets the stage for Vichy and the collaborationist regime, a lot of the French Right. This goes all the way up to today with the RN, the Rassemblement National. It goes all the way up to today; these genealogies in a lot of ways, but this is a very coalescing moment for the French Right.

MacGuire looks at this, and he appears to be acting on behalf of this consortium of American businessmen that was known as the American Liberty League, which involves the Duponts, the heads of some minor but important oil companies in the U.S., the McCann Erickson Ad Agency, General Foods, like a whole bunch of these different people. His boss, who is the treasurer of this group– his boss is like a shadow of Smedley Butler, who has traveled the world as an American spy in American military intelligence, operating intelligence networks overseas, sets up an intelligence network in Europe, and things like that. Grayson Murphy is his name. He’s also a financier in New York, but anyway.

So, MacGuire basically comes to Butler and is like, “We’re going to do what they did in France. I want you to model this effort. You’re going to use the American Legion, and we’re going to model it on one group in particular, la Croix-de-Feu, the Fiery Cross. We’re going to march into Washington, and we are going to intimidate. We’re basically going to surround the White House, show FDR that he doesn’t have control over the country or Washington anymore and that his life is in danger. Either he will resign entirely or delegate power to–,” and these are the years before the 22nd Amendment, so the order of succession is not fully established as it is in the U.S. now.

Basically, their plan is that they’re going to demand that Roosevelt name an Assistant President, as they call it, or a Secretary of General Affairs, but basically a guy who they will name to be this super cabinet position and to either delegate all of his presidential authority to this guy or resign in favor of this guy. This guy, who they’re imagining, will then become, effectively, the first fascist dictator unelected of the United States. Again, they’re modeling this off of the March on Rome when Mussolini and his black shirts converge on Rome and basically convince Victor Emmanuel, the King of Italy, to depose the Italian government, put Mussolini in as this assistant King, essentially, and then back off and not really have any political power anymore.

MacGuire even says to Butler, as Butler testifies in front of Congress, “Maybe we’ll do with FDR what they did with the King of Italy.” Butler doesn’t go along with this, thank God, and he instead blows the whistle, goes to Congress, and testifies about everything that he knows. Congress conducts a very brief and muted investigation that goes nowhere, and no one is held responsible.

Effectively, the only person who is definitively connected to the coup in terms of the– first of all, this is laughed at in the press. The Commission in Congress and it’s headed by John W. McCormack, who ended up becoming speaker of the House. He, actually, is the longest-serving speaker of the House of Representatives. Ultimately, they say, “Butler seems to have been telling the truth. Our very limited amount of research indicates that something like this probably was discussed,” but they don’t bring any of the Duponts or the heads of Phillips Oil or Sun Oil, they don’t bring any of these guys in to testify. Then MacGuire ends up actually dying a couple of months later at the age of 37. No evidence of foul play. It is interesting timing, though. MacGuire’s brother blames Smedley Butler. He blames him for all of the stress that he caused on Jerry MacGuire. That’s basically it.

For American history since then, this is sort of treated as this weird footnote, this weird afterthought. A lot of people to this day who have heard of this thing doubt that it existed. Some people claim that Butler did this as like, a self-publicity move. I don’t think that’s accurate at all. I see a lot of reason to believe that it happened. I also have not found a smoking gun, but nonetheless, Butler did not do himself any professional or personal favors by going up against these big guys like he did. He actually, in a lot of ways, becomes more marginalized in society, which then puts him in the position that he’s in the rest of the 1930s, which is just as a professional activist and gadfly, giving speeches like, War Is a Racket. Then he dies in 1940, having unsuccessfully tried to keep World War II from happening. I’ll get to that in one second. It’s the last little coda here. I don’t think he did himself any favors by doing this.

Basically, exposing this coup plot was enough to keep it from happening, and that FDR needs the oligarchs to go along with some of his New Deal reforms. He doesn’t really need their entire buy-in, but he also needs them in some cases to stand down against him because they still have senators in their pocket who could really cause trouble for his legislation, things like this. My guess is that it’s basically an agreement between him and the Duponts. I don’t know about this, but I’m just theorizing. It’s not a theory that’s unique to me, but it’s just like, look, I’m not going to try you for treason, but you have to let me do some of these New Deals.

The last thing I’ll just say about the end of Butler’s antiwar career is that the irony is that he’s trying to keep America out of World War II, but in a lot of ways, he’s trying to keep World War II from happening in the first place. He doesn’t really find himself on the side of the America firsters. He certainly doesn’t find himself on the side of the pro-Nazi, like Charles Lindbergh types. He’s much more concerned about a war in the Pacific because that is where his experience has been. He doesn’t like fascists. He denounces fascist, as we talked about. He got court-martialed for insulting Benito Mussolini. He’s not pro-fascist at all, but his feeling or his dream is that he can keep World War I from repeating itself and to keep another generation of American men, because they’re all men at the time, from going through the horrors, the psychological trauma, the PTSD, and the moral injury that he experienced. The irony is that he has done more, probably than almost any other single individual, to make World War II an inevitability.

He died of cancer in 1940, the day after the French surrender to the Germans in Compiègne in the Battle of France. In a lot of ways, that project ended up being a failure because, obviously, World War II did happen, regardless, and the United States did get involved. He remains a symbol and an important rallying point for somebody who learned from his own experience, who learned from his traumas, and who learned from the traumas that he put other people through to try to speak out. Maybe it was too late for him. Maybe it’s too late for us as well, but we can look back to him as a model of a deeply flawed, and deeply imperfect person who nonetheless, despite himself and belatedly, ended up speaking out.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, I hope people read your book because there are a lot of parallels between those times and how he was trying to fight the elite, the bankers, and the defense contractors, especially toward the end of his life. Now, we heard Kamala Harris saying that she wants to make sure that America has the most lethal military. Trump goes on about strength. I mean, both parties are essentially propping up war and ensuring that contractors just profit from it. There are a lot of similarities and parallels there.

Jonathan M. Katz

100%, yeah. His book, which becomes a slogan, War Is a Racket, what he’s identifying is what ends up being called the military-industrial complex. What he is identifying is that all of these interests, banks, especially in his view in his time, munitions makers, like arms dealers, people who make the weapons of war, that it is in their interest to make sure that war is happening all the time so they can make good on their investment.

I don’t think that he was even able to really pull back the camera enough. Oh, he did to some extent. Well, he did, actually. He did because he talks about it in a very famous essay that he writes for a magazine, which is sometimes confused with War Is a Racket, but he writes about all the things that he’d done on behalf of all these businesses. I’m in all these places. He says, “I made Haiti safe for the National City Bank boys. I brought light to the Dominican Republic for the sugar interest. I made China the–”.

Talia Baroncelli

The Canal in Panama, for example, that was directly benefiting J. P. Morgan and the [inaudible 00:34:21] brothers.

Jonathan M. Katz

Exactly. China for Standard Oil and Nicaragua for Brown Brothers. He talks about all these things. Then he says, “I was a racketeer for capitalism,” which is where the title of my book comes from. He says, “Looking back on it, I could have given Al Capone a few hints. The best he did was operate in three city districts. We Marines operated on three continents.” So, yes, he sees the way that these things fit together belatedly, but he calls them out, and it is as true today as it was then.

It doesn’t mean that the answer is the obverse of American imperialism or this negative American exceptionalism, as it’s sometimes referred to. That everything bad that happens in the world happens because of the United States, and that anything good that happens in the world will happen in the defeat of the United States. That Russia defeating the United States in a war or China defeating the United States will somehow make the world better. Butler didn’t believe that either because if Butler thought things like that, then he would have then been like, “So let’s team up with Nazi Germany and fascist Italy.” He was able to see around that as well, but it does mean that there are vested interests.

When you look at something like Ukraine, it’s very important to understand all sides of this. That Russia invaded Ukraine. They didn’t have to do that. They weren’t forced to do that. They may have been responding to geo-political pressures as they saw them, but there’s no excuse. Two wrongs definitely don’t make a right, and two war crimes don’t make peace. At the same time, it has been very much in the interest of the American military-industrial complex, in particular, Lockheed, Boeing, and these major corporations, to flood Ukraine with weapons and make sure that it’s bolstering their bottom line and to keep that fighting going for as long as possible.

Butler didn’t have any easy answers, and I don’t think there are easy answers, but I think it’s also just very important to understand how these things fit together and the ways that the past and past experiences can inform our understanding of the present.

Talia Baroncelli

Jonathan M. Katz, it was great speaking to you about this book. I really hope people read Gangsters of Capitalism, and thanks so much for joining us.

Jonathan M. Katz

Thank you.

Talia Baroncelli

Thank you for watching theAnalysis.news and for supporting the channel. See you next time.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | TuneIn | Deezer | RSS

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter

Jonathan Myerson Katz is an American journalist and author known for his reporting on the 2010 Haiti earthquake and the role of the United Nations in the ensuing cholera outbreak.