This is an episode of Reality Asserts Itself, produced on January 17, 2017. On Reality Asserts Itself, Nina Turner, former Ohio State Senator and leading Bernie Sanders surrogate during the primary, tells host Paul Jay that she grew up poor, believing in the Democratic Party and the Clintons, but she came to understand the failure of the Party to serve the needs of the African-American community and poor white workers.

PAUL JAY: Welcome to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay and welcome to Reality Asserts Itself. One of the breakthrough personalities of the 2016 election campaign was a former Ohio State Senator, Nina Turner. She appeared on behalf of Bernie Sanders in hundreds of events and more or less became the main face of the campaign after Senator Sanders himself. Nina is a college professor, a public speaker, frequent media commentator and author. She’s worked in the leadership of the Ohio Democratic Party and is an elected member of the Cleveland City Council. She was the Democratic candidate for Ohio Secretary of State in 2014 and, more recently, as I said, a national surrogate for Senator Bernie Sanders during the 2016 Democratic Presidential Primary. Today she appears regularly as a political analyst on national television and radio networks and she’s been recognized by “The Root” which listed her as one of the Top 100 Most Influential African-Americans in the United States in 2014, and by Cleveland’s “Inside Business” magazine as one of the top 25 most powerful people in Northeast Ohio for 2015. And I should also say we’re in the midst of discussions with former Ohio Senator Nina Turner for hosting a show on The Real News Network. So, if that’s considered any kind of conflict of interest in this interview, well, it’s now transparent. And Senator Nina Turner joins me in the studio. Thanks for joining me.

NINA TURNER Thanks, Paul Jay.

PAUL JAY: So, on Reality Asserts Itself, as people know, we always start, or usually start, with a person’s biography… growing up. We’re interested in how people’s political opinions, world view, were formed and then we start getting into the issues of the day and that’s what we’re going to do with Nina. So, first of all, thanks again.

NINA TURNER Thanks for having me.

PAUL JAY: So, talk about growing up. What were sort of the conditions you grew up in? And to what extent was there political discussion in the household? And if so, what kind of… what were the ideas?

NINA TURNER Yeah, conditions were not ideal, in the sense economically, but certainly my siblings and I knew that we were loved — and that should be the foundation of any family. I’m the oldest of seven children. It’s hard to believe when I look back on that to say I’m the oldest of seven children. And my parents got married really young. They were 17 and 18 when they got married, and just kind of had this relationship on and off and eventually got divorced. My mother was married three other times beyond my father, but the majority of my life grew up in a single-parent household. And unfortunately my mother died at the age of 42 years old. Aneurism burst in her brain, totally unexpected. She was in a coma for a little while and I, you know, like it was yesterday, just as the oldest child, had to make the decision about when to pull the plug. And I often have flash-backs about a woman who tried really hard, my grandparents were solidly middle class. My mother was an only child. But, you know, life happens to lots of people and it certainly happened to my mother but it wasn’t… She loved her children very, very much. And one of my biggest heartbreaks is that she did die so young. I was 22 and my youngest sister was 12. And not only did my mother die at a young age, you know, I think about the poem by Langston Hughes, “What Happens To A Dream Deferred,” or his “Mother to Son” poem — “Life ain’t been no crystal stair.” I think about that when I think about my mother who never lived to see her daughter become a first generation college graduate or take oaths of offices, becoming a City Councilwoman and a Senator, or working in an administration. And by all measures that social scientists put out there when they study what is the likelihood, you know, my siblings and I were at an disadvantage from the beginning.

`PAUL JAY`: Yeah, the family was poor? I think you’ve told me before.

NINA TURNER Oh, yeah, no doubt about that.

PAUL JAY: Sometimes there was no food.

NINA TURNER Yeah, there were times that there was not food. My mother struggled a lot on and off. My mother died at the age of 42 on the system of welfare. And she didn’t have a life insurance policy, so here I am at 22, have my son, my husband, we have now six people that we are responsible for, plus our son, and we’re 22. That’s a lot. That’s a big, big burden and I had moments of, “How in the hell am I gonna make it here?” You know, but my mother was a spiritual woman, she was an evangelist. So, I think, a lot of my passion and energy I certainly attribute to my experience in the black church but it was really that faith in God that really drove and pushed me. But also the influence of my grandmother, my mother’s mother who died four months after my mother — that was a hard year for my family and I. My grandmother died of lung cancer.

PAUL JAY: What year was it?

NINA TURNER It was 1992, so it was… it was a year like no other, so. But I do thank God and I do attribute a lot of hard work but also faith.

PAUL JAY: You went to work young?

NINA TURNER I did.

PAUL JAY: How old were you?

NINA TURNER I was about 14 — not so sure it was legal to do that — but I did and I helped my mother. I would supplement the family’s income.

PAUL JAY: Now, you told me off camera that–

NINA TURNER You can’t talk about what we talked about off camera. (laughs)

PAUL JAY: Oh, I can — that your brother…

NINA TURNER Yeah.

PAUL JAY: …votes Republican.

NINA TURNER He does. My brother, not only does he vote Republican, Paul, he is a Conservative, exclamation point, Republican.

PAUL JAY: So, and you’re only two years apart in age. He’s two years younger than you are?

NINA TURNER Yeah.

PAUL JAY: So, explain how you come out of the same conditions, the same household, similar experiences, I would guess.

NINA TURNER Yeah.

PAUL JAY: And at least, on the face of it, polar opposites on politics.

NINA TURNER We are. I’m still trying to… I want some DNA testing actually (laughs) because my brother… But I joke on the campaign trail that I come from a mixed family — my brother’s Conservative Republican. But he helps me to have insight and to have more compassion or at least… You know, Steven Covey said, “Seek first to understand and then to be understood.” He broadens me in that way and I try to have more understanding, even when I don’t agree with the other person. And my brother is just flat-out brilliant. I’m going to say it here first, though, over the news… (laughs) that he is, But yeah, sometimes I question our interpretation of our experiences.

PAUL JAY: So, how do you account for your own politicization? And let’s kind of go through that. You told me again, off camera, that you supported the Clintons and you used to — and you’ve been fairly open in the election campaign — of being very critical of Hillary Clinton. But you used to… you bought into the Democratic Party and Clintonism.

NINA TURNER I did, yeah. I was younger then also and, usually, you know, my mom who was, you know, not necessarily… I mean, her and my dad, I just found out from my dad, actually campaigned for Mayor Carl B. Stokes before he was Mayor Stokes and he was the first African-American mayor of a major city. And they would hand out leaflets. So, you know, I kind of feel like I’m coming full circle. But in my household, you know, my mother would say, “Okay, we’re going to go vote and this is who we’re voting for.” You know? And so, like a… I listened to my mom. I believed in what she had to say and was really glad that she was engaged, but a lot of African-American community just really believed in the Clintons. But now that we know, in terms of the Crime Bill, Welfare Reform, there were a lot of policies that were pushed that were detrimental to the African-American community. Not for one snapshot in time, but generationally. And so, when you know more, you know, you should definitely do more and analyze differently. And so, now I look at the Clinton years through a different lens. That doesn’t mean that President Clinton didn’t do some good things but overall some of those policy positions that were taken by Democrats — and even African-American Democrats, co-signed the Crime Bill. And looking back on that, generationally, how it has upset the fabric of the African-American community, and we look at whether or not we should take low-level, non-violent, particularly drug offenders, whether we should put them in an entire system that really makes their lives worse, or whether we as a country should treat those types of people, especially if you’re addicted to drugs, as if it is a medical situation instead of a criminal situation. So, I’ve, you know… I’ve come… Muhammad Ali used to say, “When I was 20, you know… If at the age of 50 I still think the way I did at 20, something’s wrong.” And so that’s how I feel, I have more knowledge and insight and information and I’m a different kind of a Democrat.

PAUL JAY: Did you, when your mother dies you’re 22, your brother is 20…

NINA TURNER Yeah. My baby sister was 12. We just go down the line.

PAUL JAY: So, you become… you have some of the responsibilities of mom for your…

NINA TURNER: A lot, but I’ve always had that, even when my mother was alive. She really leaned on me and I remember her saying to me, “I’m so glad I had a daughter first.” And that means a lot to me, especially when I reflect on my mother’s life, and my grandmother had such influence on me. My grandmother was born in 1913. She didn’t have a formal education. She was born at a time where blacks, and in particular black women, you know, were not treated well in this country. I often say she was robbed of opportunity, even though she never once complained and she was one of the smartest women I’ve ever known. So, when I tell lots of the stories, and the strength that I get, it really does come from the spirit and the fight of my grandmother.

PAUL JAY: When do you start to be kind of cognizant or aware of politics — that there is such a thing as a Democratic Party? When does that become on your radar?

NINA TURNER: The party, in terms of the structure and what I’m engaged in now, that was not my orientation at a younger age. I remember being a junior at Cleveland State University with a couple of friends of mine and we started an organization called Students for Positive Action. We were gung ho. We believed in the power of the ballot box and we wanted to empower poor people to take control of their lives through making sure that they vote, that that is the key — that all paths lead to the ballot box. And we went out to a community in Cleveland called Hough. You may remember some of the Hough riots that happened in the ’60s, but Huff was a very economically-poor — and I put the emphasis on that, because a lot of time people look at poor communities, particularly African-American communities and think that those communities are lacking in love and hope and dreams and desires. And that’s not true. It’s one thing to be poor economically. It’s another thing to be poor in heart and spirit. And what I find in these communities, just like in my household, there was lots of spirit. There was lots of love. But what was missing is access to opportunities. And we know that things are not equal in this country and we’re still fighting. “Working poor” means something — it means people are working yet they are still poor. But my orientation was not necessarily to a party structure. But my commitment was to the people. And my belief that the Democratic Party offered that stronger pathway in that. Now, sometimes I question that to this day, especially what happened in 2016. But working and registering people to vote, was really my first orientation to grassroots. A Councilwoman by the name of Fannie M. Lewis in Cleveland, who was a legend, she’s since deceased, but she was born in 1921 and she just really believed that her community deserved uplift and they deserved leadership and she was a fighter. So, my friends and I had the opportunity to work side by side with her. That was really my first kind of grassroots display of really working politically.

PAUL JAY: To what extent, I mean, I call it… you know, I grew up in Canada and to me this is, Americanism I’ve always seen as a kind of a religion. When I was young, my grandfather was dying in Los Angeles and I went to… my mother went down to be with him, so they put me in an American school, a school in LA. And for the first time there, I looked around in the morning, everyone puts their hand on their chest and I…

NINA TURNER: Yeah, I pledge allegiance…

PAUL JAY: …couldn’t believe it.

NINA TURNER: …to the flag of the United States of America.

PAUL JAY: I was Canadian enough that I didn’t want to do it.

NINA TURNER: Yeah.

PAUL JAY: But the idea of Americanism, and growing up surrounded by that, I know most of the… all the schools in Baltimore pledge allegiance in the morning. But to grow up in that black…

NINA TURNER: Yes.

PAUL JAY: And as you start to become conscious of white supremacy and that’s part of Americanism.

NINA TURNER: Uh huh.

PAUL JAY: When does that become real for you? When does that become a part of your awareness?

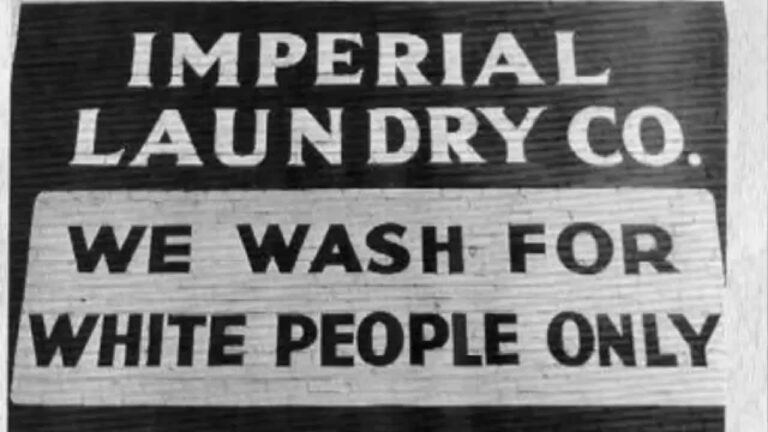

NINA TURNER: It’s always been a part of my awareness. It’s deeper now but, you know, just looking at my grandparents. Both my grandmother and my grandfather, they never really complained but they had it hard. You know, my grandmother grew up, you know, understanding very well that some of the deficiencies she had — I mean, imagine not only having a third-grade education but she really made the best of a bad or an imperfect situation. I would have to say my consciousness really peaked during my college years when I’m taking African-American History courses. I’ll never forget my first class at Cuyahoga Community College, where I am a professor there today, and I’m looking at my schedule and I walk into my Black History class and I see a white woman with blonde hair in front of the class and I’m looking at my schedule and I’m looking at her saying, “This can’t be real,” because, of course, a white person could never teach black history. But it was Dr. Dorothy Salem that really opened my eyes to the beauty and the prowess and the tradition of African-American History and that African-American History is America’s history. And it was there that I was able to overlay some of my experiences with some of the academic realities, that generation after generation of African-Americans were chattel in this country. That African-Americans were considered three-fifths of a human being in this country. That this country was built on the backs and the sweat and the blood and the tears of African-Americans — and that, even today, there is some connections. There was an article just in the New York Times this week about how New York Life, a mega insurance company, insured slaves for white slave owners and they were not the only insurance company. But just think about that — the United States of America, these things happened. So, it was the melding together–

PAUL JAY: Like you insure property.

NINA TURNER: Right, because they were chattel, like your cat, your dog, your car, you know — they were. And there are remnants of that today that, in many ways, this country does not want to admit. That it would not be America without that kind of labor, and what we did to Native Americans. And only because of Standing Rock have our Native American brothers and sisters, are at the forefront of a fight, when their land was taken from them and the Trail of Tears and all the other bad things, horrible, inhumane, immoral things that we have done to people of color in this country. And it is because of Dr. Dorothy Salem that I decided to even major in History with a concentration in African-American History and that is the reason why I teach it today. It just drives me crazy sometimes, you know, getting to the political realities of the day. I believe it’s easy to point the finger at Mr. Trump and, yes, he has said some awful things during the campaign that he has to be held to account. But if we really want to get at the root of institutional systemic racism, it’s bigger than Donald Trump. It’s bigger than any one person.

PAUL JAY: As you become politicized in Cleveland, if I’m right about this, it’s also at a time of the emergence of more black politicians getting elected.

NINA TURNER: Yes.

PAUL JAY: And some people call the emergence of a black political elite.

NINA TURNER: Uh huh.

PAUL JAY: And within the Democratic Party, I often hear this notion of, you know, we need to get the Democratic Party back to the party of the working people. Or, I mean, we know the Democratic Party was the party of the slave-owners.

NINA TURNER: You bet. My brother reminds me that every conversation. (laughs) Honestly. No, it was, and we’ve got to confess that. Yeah.

PAUL JAY: And you… I guess what I’m getting at is, as you become more active and involved in municipal politics and in state politics through the structure of the Democratic Party, it starts to become part of your identity, part of your loyalty.

NINA TURNER: Yes, very much so. And I often say I’m loyal but I’m not blindly loyal — and you have to be able, if you love a thing, to critique it. You know, one of the things James Baldwin, the novelist, the great American novelist, activist, when he said about this country, he said, “I love this country more than any other country in the world,” and I’m paraphrasing him. He said, “And because of my love for this country, I have the right to critique it.” And so I take that and I overlay that over Democratic Party. I’ve been a life-long Democrat. I’ve given all of my service to this party, under the banner of this party — and because I have, I have a right to critique it. And it was really my entree into the Sanders campaign that really opened my eyes more than ever, and so, I do critique the Democratic Party even more because we are supposed to be the party of the working class, that we owe it to make sure that we are — that we’re not just whispering sweet nothings in people’s ears. The fact of the matter remains that it is true, that most of American cities, urban area cities, where other people live other than blacks, because that’s a pet peeve of mine — people say “urban,” they think I’m saying “black”. No, it means “city” and the last time I checked white people live in cities, Hispanic people, but we… But we owe it, if crises are happening in urban America, and most of the mayors are Democrats, then Democrats need to take responsibility.

PAUL JAY: Yeah, and we’re in Baltimore and Cleveland…

NINA TURNER: And I’m in Cleveland. And, you know, you and I talked about this, which just drives me mad. You know, there was a Fight for $15 in Cleveland that was pushed by SEIU, trying to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour. The Cleveland City Council manipulated the system — the body that I served on, that is all-Democrat. And Democrats are not homogenous, so I get it. If you believe that the Fight for $15 will hurt the city, I get it. Let’s debate it. But they manipulated the system to prevent it from getting on the ballot this November. So, it’s supposed to go on the ballot next year. And Democrats asked the Republican Legislature to place an amendment on a bill to prevent this from even getting on the ballot next year. Not just for Cleveland, but now the way that it is written, that no municipality can force a minimum wage increase above and beyond what the State does. Democrats did that. So, back to your point about, I am going to call out Democrats when they’re wrong, praise them when they’re right — and the same way I’m gonna do Republicans. I’m not going to be one-sided. But because Democrats enjoy the majority of the votes from the African-American community and we are in worse conditions economically for a party that says it stands up, but we don’t see the real practical results of that, people have got to be called out for that, Paul Jay. And then we have left behind working class whites. There is no doubt about it, that it can be both. I remember Reverend Jesse Jackson saying that the Democratic Party has to talk about both class and caste. They go hand in hand. We can both say that poor working class whites are being left behind and poor blacks and poor Hispanics and poor Asians, and Native Americans, but disproportionately people of color suffer the burden the most. But then we have to fight. What are we going to do? When you’re in power, do something with that power. And stop worrying about the next election, more than you worry about the next generation.

PAUL JAY: Okay, we’re going to pick this up in part 2.

NINA TURNER: Okay.

PAUL JAY: So, please join us for part 2 on Reality Asserts Itself with Nina Turner, on The Real News Network.

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter

“Nina Turner is an American politician and television personality. A member of the Democratic Party, she was a Cleveland City Council member from 2006 to 2008 and a member of the Ohio Senate from 2008 until 2014. Turner was the Democratic nominee for Ohio Secretary of State in 2014 but lost in the general election against incumbent Jon Husted, receiving 35.5 percent of the vote. Her politics have been variously described as progressive, left-wing, or far-left.”