This interview was originally published on October 7, 2013. In this episode, Frank Hammer tells Paul Jay about being inspired by the national liberation movements and the struggle against concessions as a response to the outsourcing of jobs.

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay in Baltimore. And welcome back to Reality Asserts Itself.

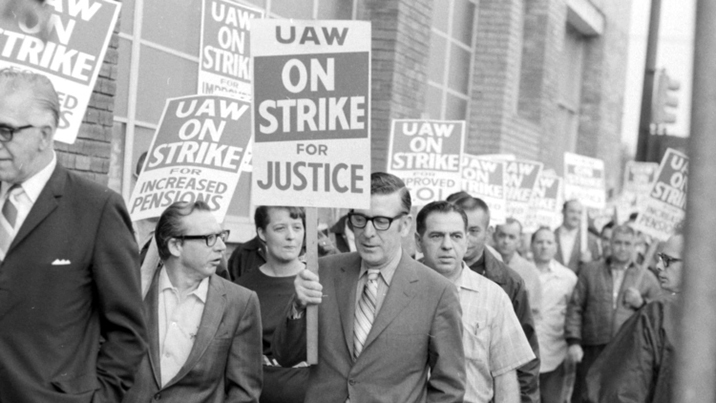

We’re talking today with Frank Hammer, who now joins us in the studio. Frank’s a retired General Motors employee. He worked at GM for 32 years. He was the former president and chairman of the United Auto Workers Local 909 at the GM Transmission Plant in Detroit. He’s a adjunct faculty member at Wayne State University.

Thanks for joining us again.

FRANK HAMMER, COFOUNDER, AUTOWORKER CARAVAN: Thank you again.

JAY: So if you haven’t watched part one, I think you’ll want to, because part one kind of tells us who Frank is. And just to sort of quickly recap, Frank was at Berkeley in the early ’60s on his way to be an architect, and with the Free Speech Movement, the Vietnam War, and other factors, I’m sure, kind of left that track and decided to get a working-class job, and not long after was working at General Motors in Detroit.

So just a little bit more on that decision. Like, was there a day where you really made–there had to be a day where you actually made the decision, this I’m changing the course of my life.

HAMMER: Yeah, there was a transition for me coming out of the University of Michigan. Of course, I wasn’t by myself. There were many other students who wanted to become activists in the working-class movement. I had already been at picket lines while I was in grad school, and I and many others gravitated in that direction.

So I started to work for a agency that produced material for community newspapers. I got that close. And I decided, no, I really needed to get right into the factory and become one among the people that wanted to organize. And that happened, like, in 1972.

JAY: There does not seem to be so much of that going on anymore, you know, people getting politicized, the sort of–and deciding that where the fight is is in the working class, as you say, and then going there. That seems to be something not on activists’ minds these days. I know there’s some, but not as it was in the late ’60s and ’70s. Even there was–even amongst, I remember–there was a trend within the Catholic Church: the priests were going to go to factories. And many did. There was a real focus on the working-class movement. And since that time, there actually seems to have become almost a detachment for much of the left from what goes on in the working class.

HAMMER: Well, I think that at that moment in time the working class looked rather strong. One of the things that drew me to Detroit and to the auto workers movement was the insurgence that was going on, especially with the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, who were really rattling cages in Detroit and building a working-class African-American movement. This was very inspirational to many of us. And that was one of the reasons that my wife and I came to Detroit and why I decided to get an auto job, because there was an element of conscious resistance to the way things were and a movement for change that really at its core was revolutionary in its direction.

JAY: We were talking in between breaks. You know, I asked you the question, you know, why aren’t more people making this decision. And, you know, there’s been a lot of talk that during the Vietnam War, more now as compared to during the Vietnam War, and some again–always, I should say, some are, but not on the scale that was happening during Vietnam. And the conventional wisdom is that it was about the draft. But a lot of people back in those days, like you, they actually put themselves in harm’s way in terms of the draft, and it wasn’t to avoid the draft. Certainly a lot of students were drawn into the fight because of the draft. But there seems to have been some other factor. And we were talking about the mood. There was kind of a global revolutionary mood in the 1960s. I mean, how much that did that sort of affect you?

HAMMER: Yeah, I think that–very, very important. I think the context for somebody like myself at that time was defined by liberation movements in Africa for independence and for anti-colonialist struggles. There was a very inspiring struggle going on in the Middle East with the Palestinian liberation movement. You of course had the civil rights movement in the South. There was also a source of inspiration. And also the Latino movement in the United States. You had the women’s movement in the late ’60s. So all these movements that were moving in the direction of liberation and away from accepting oppression. And I think a lot of students were inspired. There was also a fairly active working-class movement. I mean, you had miners in Harlan, Kentucky, for example, that were waging a heroic struggle, that this is one example.

JAY: There was a sense–’cause, you know, I grew up in the same period–there was a sense that you could actually fight for something. You know this idea. There’s this slogan a better world’s possible. But it really actually felt that way. And maybe for a lot of people, young people now especially, it kind of doesn’t feel that way. And they want a better world, but it’s not–there wasn’t a mood of the ’60s where it actually felt like you could touch it.

HAMMER: The movement in the ’60s was very much affected by the example of the Cuban Revolution, which was 1959. I mean, I remember young people that I was with that made trips to Cuba that went there to cut sugar, cut sugarcane, and came back with, you know, a very–with a great zeal about the socialist revolution that was going on in Cuba. The fact of the National Liberation Front in South Vietnam was a great inspiration to many of us. It wasn’t just that we were against the genocidal attacks by the U.S., but also we were inspired that such a people that was not particularly technologically advanced could actually mount an effective resistance was an inspiration. You had the revolution that happened in China, which was, you know, 1949 and was developing from the ’40s through the ’70s. And so I think all these gave you the idea that not only did we want a different world, but that a different world was in fact possible.

JAY: And then things didn’t seem quite to turn out the way a lot of people thought they would. You had a situation in China where, you know, the Cultural Revolution seemed to have caused a lot of disruption. And eventually, you know, you have the rise of what–as we know now, a very capitalist China. You know, I think in the ’60s a lot of people had already lost any kind of illusions about what the Soviet Union had become, and certainly by the ’70s and ’80s, most of the left that might have thought the Soviet Union represented some kind of new world–and I think maybe a lot of people thought at one stage it did, but by then didn’t. And for a lot of people, they got cynical, and a lot of people kind of gave up, and a lot of people said, well, you know, I might as well just find a career and make money and build a family, ’cause there’s not much we can do anymore. And you didn’t. You were–continued–you were–you became president of the local, and you were–you know, I don’t–as far as I understand, you didn’t miss a beat in terms of the level of intensity of your activism.

HAMMER: Right.

JAY: Why?

HAMMER: Well, I think that–first of all, I think we have to understand that the world of the autoworker in the early ’70s, when I first started in, was very different from the one we have now. Then you could literally walk out of one factory and walk into the other and pretty much get a job. Okay? That’s not–the material reality is very different these days. Right? My union in the ’70s was 1.5 million strong. Today it’s 400,000.

JAY: Yeah, I had the same experience. I went to Windsor in–I guess it was the early ’70s, and within three days I had a job at a punch press factory.

HAMMER: Yeah. It’s very different, and from the point of economics, and in the United States in particular, very different world.

So, you know, I went into the factory. And I think part of what happened is that, you know, I joined. There was a sort of a generation of workers that went in at the same time that I did who I got to really, really, really appreciate and become one with them, and they became one with me. And this has sort of kept me motivated and very interested in trying to continue to fight for change.

JAY: My experience working in big plants and big–you know, I worked as well. I mean, it wasn’t so much a conscious decision to go get a working-class job. I just needed a job, and that was the only job I was qualified for. But, you know, I worked on the railroad, I drove a truck, and all this. But walking into one of those big–like the punch press factory, one of these big industrial places, you understand class and class struggle in a completely different way. It’s not some abstraction. It’s not a theoretical concept. It’s like every single moment the intensity of, you know, can they make you work this much faster, can the foreman breathe down your neck this much more. But it’s big. Like, I think the one I was in must have been about 1,500 or 2,000 workers, the scale of the whole thing.

HAMMER: Yeah. Yeah. I think that that’s part of where the strength of the working-class at that moment in time that we could–you know, that you could experience. I mean, my factory, the second factory I worked in, was 4,000 workers. Well, that’s massive. And not only that, but we worked shoulder to shoulder on some of the departments in the factory. I mean, we worked on assembling rear axles. And, you know, we were–literally were rubbing elbows. So there is a certain element of strength that we see collectively in numbers. Right?

Today I visited my factory, not too long ago, and if you look down the aisle, you don’t see workers; you know, you see machines. And we’re down to 400 people. So we’re–it’s a different–.

JAY: Four hundred.

HAMMER: Four hundred, down from 4,000.

JAY: Four thousand to 400.

HAMMER: Yeah. And that’s not unusual. That’s actually typical for the plants that have remained open. Yeah.

JAY: So, I mean, obviously your life story is a long story, and we can’t do the whole life story. But one thing that happens to you as an activist in the union which I think is sort of critical to understanding you and the politics of Detroit is that you start coming more and more into conflict with the leadership of the United Auto Workers and you start–essentially your fight is almost, sometimes, if I understand correctly, as much against the UAW leadership as it is against GM, ’cause I guess you saw them as an alliance with each other. When does that become clear?

HAMMER: Probably the day I walked into the factory. And I had some understanding of the role of the UAW before I went into the factory. So it wasn’t news for me. But, you know, I think that the UAW had, even under Reuther–and I think it’s very important to understand Reuther correctly–had embarked on this social compact with the employers. And the theory was you scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours. And I think that maybe for a time that was operative. And I don’t know. From early on in my life, I believed in really practicing democracy and democratic practice. And that’s where we bumped heads.

JAY: Yeah. We’re in Baltimore, so if you’re hearing a siren, this a part of being in Baltimore. We have a–we’re building a new studio, and once we do, you won’t hear all of this, but right now, lots of sirens in Baltimore.

HAMMER: Yeah. So, anyway, so a lot of the fights were about involvement, participation by the rank-and-file. The UAW has, from the time that I’ve been in the factory, wanted to run an operation sort of like as a service model, so that, you know, you leave it to us, we take care of it, and you, in the meantime, you just do your job, and so on.

And my concept of unionism was very different. It was no, no, we are the union, and if we’re going to be the union, we have to be engaged in the decisions of the union. And through education we become much stronger and much more committed as a union to the concepts of solidarity, to the concept of militancy, to the concept of fighting for one’s rights collectively. So that’s where we run into conflicts. And I became kind of a thorn in the UAW’s leadership side, and we did have ongoing wars. And oftentimes I would encounter the war more with UAW leadership than I would with the company, although never mind I was always in the fight with management.

JAY: Now, there’s–one of the critiques of not just UAW but to some extent many if not most autoworkers themselves is that they had it pretty good, I mean, even though there was an intense fight. And one of the reasons autoworkers had it pretty good is ’cause autoworkers, you know, got organized early, you know, in terms of 1930s and such, and there was a massive fight to establish the Auto Workers Union, you know, including gun battles and such. And, you know, if people want to look into that history, it was a fierce war to establish the unions.

But by the time you get into the ’60s and ’70s, autoworkers are amongst this privileged tier of the working class that do have well-paid jobs and good pensions and good health care. And it’s, you know, normal for an autoworker to afford a cottage and know their kids are going to go to university.

On the other hand, you get elected as president and chairman of a local for nine years, and you’re a pretty open lefty. So how does all that jive? ‘Cause you would think there’d be more conservative politics amongst the autoworkers, given how well they were doing.

HAMMER: My plant had a fairly conservative tradition before I arrived. So you’re absolutely on point, ’cause there are UAW locals that have a history of militancy, and it would have been much easier to understand.

I think that it had a lot to do with really being in tune with workers’ interests and understanding what they were and understanding how to sort of give it back to them in a way that they understood it. And I think that we ran into this problem in regards to, for example, the divisions between production and skilled trades, so that skilled trades were certainly the more elite element of the autoworkers movement. And there was a lot of conservativism there.

JAY: Now, for autoworkers on the whole, I mean, you know, I knew–as I say, I worked in a punch press factory and I got to know a lot of autoworkers. In fact, I guess I was one for a while. There wasn’t just–we were making floor panels, you know, and punching holes in them. The place was known as the finger factory, because it used to be you put a thing in and then you hit the button, put a thing in and hit the–and then one time you would do this and lose a finger, and then you get to be a foreman, because instead of paying workmen’s compensation, they promote you to be foreman. There wasn’t a foreman in the place that had ten fingers.

Generally speaking, the autoworkers I knew–and this is both on the American and the Canadian side–they thought this gravy train was going to go on forever. And, you know, there were militant in terms of fighting for their own interests–not everybody, but many. But it was still about, you know, what’s good for autoworkers. When does it start become clear to you that this gravy train isn’t going to last forever, that this actually, at least the way the industry was being run, was going to be going into decline?

HAMMER: Well, it was already in the early ’80s that the UAW leadership said, oh, we have to reopen our agreements and we have to begin to make concessions. And, in fact, very early in the ’80s, it was already a movement, of which I was a part, that said, we have to [incompr.] was opposed to concessions. We had to oppose these concessions. But you already begin to see this–as you mentioned, this gravy train begin to change.

JAY: And this is the idea that American wages are so high, they’re going to force these jobs overseas, you can’t compete with Japanese imports, and so on and so on.

HAMMER: Right, all of that. So yeah. So the strategy that was chosen by the leadership of the UAW was in fact we’re overpriced, we’re overpaid, and they sort of bought into the argument that the employer’s were–you know, that GM and Chrysler and so on were putting forward.

JAY: So in retrospect, was the argument true or not?

HAMMER: I think the argument was more complicated. And I think that the leadership was so influenced by the way the employers looked at the crisis and the conflict that they bought into the assumptions that the company would make. And I think that the reason it’s more complicated is that with what we were talking about earlier, with the transformation of China into a capitalist economy, which opened up its workforce to global capital, the same with the Eastern Bloc, that all of a sudden capital had many more workers at its disposal than it had jobs. And you could see the jobs leaving the U.S. for lower-wage countries elsewhere. You could see all this work going to China.

And there is a certain reality that we don’t have the power to shut down General Motors, we don’t have the power to shut down these companies, because they can say, look, if you don’t want it, we can find somebody else to do it. So I think that’s–there is a reality to that. But I think that the response was mistaken, and I think the response, as you can see today–.

JAY: [incompr.] terms by the union leadership.

HAMMER: By the union leadership. And that–

JAY: What should have been their response?

HAMMER: Well, I think that if they understood that we were going into a much more global operation in terms of the way capitalism was operating, that we had to move very early on to globalize our struggle and to connect with these workers in these Third World countries, that, hey, we’re all one piece, we’re all–if it’s a GM worker here–as you know, I’ve been very active with GM workers in Columbia. We’re of one piece.

JAY: And it’s kind of ironic, ’cause how involved the previous leadership of the AFL-CIO was involved in assisting the CIA to actually undermine unions all through Latin America and elsewhere.

HAMMER: Right.

JAY: They helped dig their own grave.

HAMMER: Absolutely. The response–.

JAY: Same thing in terms of cooperating for crushing national liberation movements. I mean, all of these things would have actually given these other countries, many of them–I mean, China’s somewhat its own story, but other places, they would have actually had some sense of organization and unions and such. But, you know, between American coups and the trade unions helping with that–.

HAMMER: Yes. Yeah. I mean, a prime example is the AFL-CIO helping to overthrow a government in Chile. Well, how did that benefit the U.S. working class? It didn’t. On the contrary, it made it more lucrative for employers to go to Chile and to other countries in Latin America and undermine our own situation. We should–.

JAY: Yeah. If I remember correctly–I may be mistaken on this, but I think the average wage in Latin America before World War II wasn’t that much lower than–the working-class wage wasn’t that much lower than the American wage, that if the natural progression of Latin America after World War II had been able to take place without all the military and the generals backed by the U.S., you know, you would have had a much more unionized and more sophisticated workforce and not such a low-wage workforce.

HAMMER: There was a moment–I was involved in negotiations, national negotiations in 2003 when I was working in the GM department which I thought was very indicative of the predicament that the U.S. labor found itself in. I was in a committee that was dealing with outsourcing. And at one point, one of the reps complained about the work going to Mexico and workers getting $4 an hour or whatever it was in Mexico, and that we should do something to–you know, to do something about that. And the GM rep responded, well, when we do that, that’s how we are able to pay for your wages and benefits. And the room got silent.

JAY: What was the logic of that?

HAMMER: The logic was that in other words, if we continue to exploit Third World labor at cheaper rates, we can benefit the U.S. workers by giving them more.

JAY: Because they’re making–the companies overall are making more profit.

HAMMER: Right.

JAY: So they can share share some of the plunder with the work–with, you know, some American workers.

HAMMER: Exactly. And this was the hook. And this was the hook. This was the hook. And it seems to me that it was–of course, it was also while we were supposedly benefiting from this. Of course, the companies were using it to undermine our power.

JAY: And, of course, the other side of it is, you know, there wasn’t a heck of a lot going on in organizing unorganized American workers.

HAMMER: Correct.

JAY: So outside of this privileged tier, you know, it’s by the early 1970s, wages are stuck, stagnant, or going down, and you get this whole cycle of lack of purchasing power, which leads to lack of market for cars. But for a while it’s I’m all right, Jack.

HAMMER: Correct.

JAY: Okay. In the next segment of the interview, we’re going to pick up the General Motors conversation. And we’re kind of going to jump ahead and talk a bit about the real crisis, collapse of the industry, and President Obama’s bailout, and just who was that good for.

So please join us for the continuation of our discussion with Frank Hammer on Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network.

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter

“Frank Hammer is a retired General Motors employee. He worked there for 32 years. He is the former president of United Auto Workers Local 909 and also worked at the GM department of the United Auto Workers. He’s an adjunct faculty member at Wayne State University, and he’s a passionate defender of his adopted city, Detroit.”