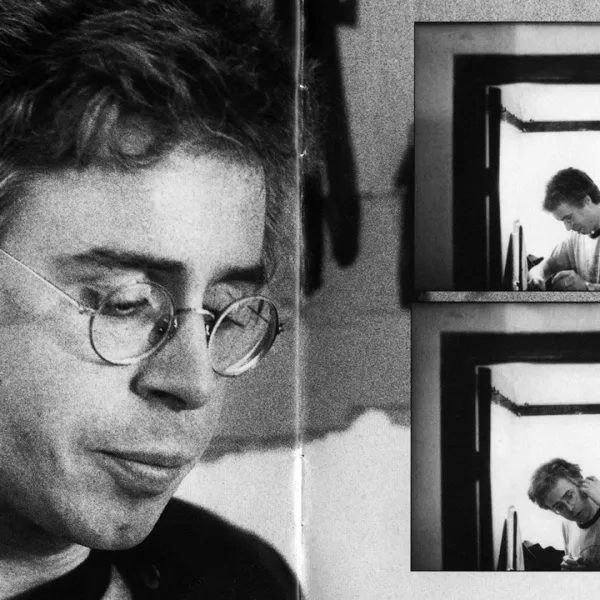

This interview was originally published on May 28, 2019. Songwriter Bruce Cockburn speaks with host Paul Jay about whether his music is ‘anti-American,’ and about his early spiritual influences.

PAUL JAY: Welcome back to Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network. We’re continuing our discussion with singer-songwriter virtuoso guitarist Bruce Cockburn. Thanks for joining us again.

BRUCE COCKBURN: Thank you.

PAUL JAY: Your dad, as your music unfolded and got more and more political, thought you were anti-American, or accused you of being anti-American.

BRUCE COCKBURN: He did.

PAUL JAY: It seems like you followed the path recommended by your teacher, perhaps, a little more than your dad.

BRUCE COCKBURN:Well, maybe, but I mean, I didn’t- I didn’t- I didn’t think about it much. I mean, I- to me that, that comment of his came up in a context of things I would say sometimes between songs or by way of introducing songs more than about the songs themselves.

[Clip of Call It Democracy – Bruce Cockburn]

That I’d be … I remember playing in Ottawa, an outdoor show that- within sight of the American embassy. And I could see the big- they had the biggest flag imaginable hanging on top of the embassy. And the embassy is like an armed camp, right. It was not like the- all the other embassies in Ottawa, which were just nice houses. The U.S. embassy is like this- this big fortress-like building.

And you can see it. And it- like, I’m looking over the heads of the audience and there’s this enormous American flag waving. And I made some crack about it. And it wasn’t intended to be, you know, a major statement of any sort. But is anybody noticing the fact that the American flag is waving bigger than everything else around here right now? Something to that effect. And I don’t know if that set my dad off or something, but he did comment on the fact that I was somehow anti-American. And he mentioned that a couple of times. And I heard it from other places, too. But I only ever heard from Canadians. No American ever accused me of being anti-American.

[Clip of Listen For the Laugh – Bruce Cockburn]

The Americans are- one of the wonderful things about this country is people are capable of self-criticism. And I mean, even-

PAUL JAY: Some.

BRUCE COCKBURN: Some. Well, even the people who vote for Trump are capable. I mean, theoretically, at least. I mean, they’re individuals. You have to be careful with any generalizations. But I think it’s one of the one of the really healthy things about American culture, is that capacity. So you know, you can criticize things- and it’s true, in this very polarized atmosphere we’re in right now, it’s a bit dicier. And it was probably this dicey in the ‘50s, if you said certain kinds of things. But in between-

PAUL JAY: People lost their jobs for-

BRUCE COCKBURN: –this golden age where- that we’ve lived in between, you know, 1950 and a year ago, we’ve been able to say pretty much whatever we wanted to. And I mean, people look askance at it, or they agree with it more than you wanted them to, or- I mean, there’s- there’s every shading of of reception [crosstalk].

PAUL JAY: But during the Vietnam War, there were certainly- people lost jobs, and-

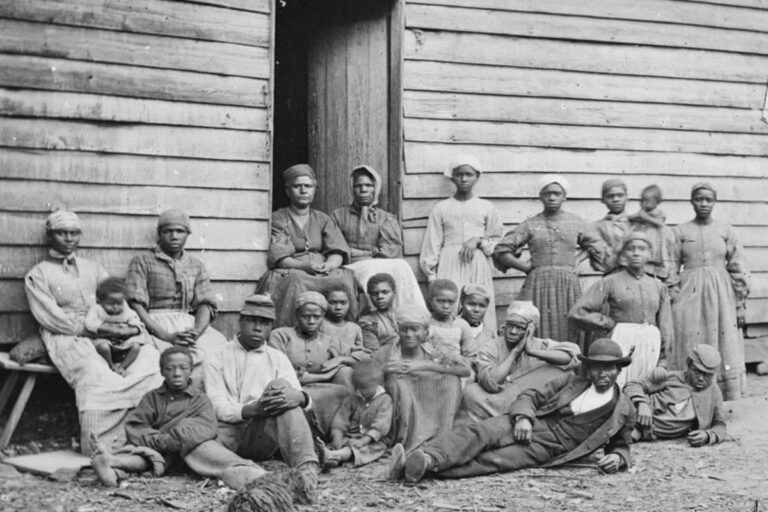

BRUCE COCKBURN: Yeah, I mean, stuff happens. People lost jobs- a lot of people lost jobs and lives during the struggles of the ‘20s and ‘30s and- and before.

PAUL JAY: Some went to prison.

BRUCE COCKBURN: There’s- you know, it’s- it’s not a monolith. And that’s one of the healthy things, too, that I think when- once something becomes monolithic then it becomes easily manipulated in the other way than dividing and conquering creates an ease of manipulation. So that’s- it’s nice that the- that we have the contrast and the variety and the tensions that we have to- up to a point. At the moment I think it’s gone a little too far in the direction it has, but a dialogue, a, you know, a dialectic, dare I say, is healthy. You’ve got to have this going, this back and forth, to have- to have a healthy culture and country.

But … so, you know, I pointed this out to my dad-

PAUL JAY: You think think this- you think this is a healthy country?

BRUCE COCKBURN: I think it’s it’s one of the healthier countries in the world. Not in terms of healthcare, certainly, but in terms of the ideals on which it was based, and the degree to which people are still willing even now to try to adhere to those ideals. I mean, it comes and goes. It’s stretchy. It’s ugly at times and-

PAUL JAY: Because your music is is mostly a savage critique of U.S. policy.

BRUCE COCKBURN: Well, I wouldn’t say mostly. Well, I don’t think that’s true. I don’t think that.

PAUL JAY: The political [inaudible].

BRUCE COCKBURN:I think mostly my music is about God. But- but I- certainly there are those songs that are very critical of certain United States … certain events that involve the United States and certain attitudes that I’ve run across. Yeah. But those attitudes are not exclusive to the United States, and the events are … you know, they- I mean, you can take America to task for its international actions in lots of areas, but it’s not unique in that respect. History’s full of countries taking advantage of other countries that were less strong. So when I criticize the United States, it’s an act of love, really, because having grown up as a Canadian with the United States- we’re always are more or less good neighbors. I mean, there were times when it wasn’t so good, the Bomarc crisis and stuff, where American missiles were discovered to have been secretly placed- nuclear missiles- on Canadian soil without asking anybody. And you know, there were moments like this.

PAUL JAY: Or they, did they- Kennedy steps in and actually helps overthrow Diefenbaker as prime minister.

BRUCE COCKBURN: Yeah, because he was really upset because Diefenbaker wasn’t going to have any of that. And Diefenbaker- that was the only thing about Diefenbaker that I liked. I thought he was terrible prime minister.

PAUL JAY: Well, he also kept- opened up that- opened up and allowed relations with Cuba. Even though Trudeau gets credit for that it was actually Diefenbaker.

BRUCE COCKBURN: Yeah. I don’t think I even knew that. I was in my teens, you know, when Diefenbaker was in power. I wasn’t paying that much attention. But I kind of- My parents didn’t think much of Diefenbaker, so I didn’t either.

[Clip of Open – Bruce Cockburn]

PAUL JAY: You described school as a prison.

BRUCE COCKBURN: High school became a- I look back on that as feeling like a prison sentence. Public school is not … I liked public school, I liked going, I like learning, I liked all the stuff. You know, I liked the relationship between me and the teachers for the most part, some better than others. But in spite of being terrified of Ms. Beachum, I was- I liked most of my teachers, and even her, at moments. You know, I saw a side of her that was likable. But by the time I got to high school it was a combination of me hitting the kind of hormone-driven period of my life that adolescence is, and of the school itself, perhaps. So all of the social stuff, it was- it was not a good time. I learned a lot, still, but I kind of learned it by default. I wasn’t motivated to work very hard, or anything, and I was uncomfortable most of the time when I was in high school.

PAUL JAY: You said just a few minutes ago- couple of minutes ago- your songs are mostly about God. And we’ll get into the music. But your relationship to God and religion- you write in the book that you were kind of intrigued by some of the, in my words, crazy bible stories. Some of the bizarre stuff that’s on the Old Testament.

BRUCE COCKBURN: When I was young, we- yeah, I mean, you know, I was introduced to Christianity through Sunday school, and basically by rote, because that was the culture. We said the Lord’s Prayer every morning in school. That was just what we did. I mean, Americans stood up and had the Pledge of Allegiance. We said the Lord’s Prayer and we sang God Save the Queen. It was- it was very British and very, kind of, Victorian Christian, I think, might be a way to characterize it, just in the culture. I mean, I had lots of Jewish friends, I had Jewish- lots of Jewish classmates who seemed to … nobody ever complained. Nobody minded it. They did their own thing. And the one Jehovah’s Witness girl that I remember being in class didn’t have to stand up for the national anthem. But you know, that was- and she wasn’t very friendly. I mean, she seemed nice enough, she just wasn’t friendly.

[Clip of Put It In Your Heart – Bruce Cockburn]

PAUL JAY: But you write about the sort of salacious parts of the Bible intriguing you, from incest to murder …

BRUCE COCKBURN: Yeah, this is- this became, you know- when I got old enough to kind of go beyond the, you know, the pious stuff that we were getting in Sunday School and the- pious isn’t even a very good word for it because it mostly was just like, well, you know, this happened, and then this happened, and then this happened. And it never- I never really understood why we were paying attention to this stuff, particularly. But it’s what everybody was doing, so I did it, too. But later on, I needed to start- I don’t remember what triggered it, but I remember discovering something in the Bible. Maybe it was the story of Lot, or maybe- you know. But, you know, start digging through the Old Testament-

PAUL JAY: You write about Sodom and Gomorrah.

BRUCE COCKBURN: Well, yeah, I mean, there’s- and that’s, like, nothing compared to some of the other stuff that’s in there in terms of sex and violence and, and whatever, right. There’s- there’s really terrible things. And- that, of course, were exciting to discover back then. It’s like, oh yeah, then they did this, and then they did that, and look at this, holy- who knew that was in the Bible? You know, we were going- my friends and I just started doing this.

And so that became my way of relating to the Bible for the long- well, not for the longest time, I guess, but for a long time, until I was led elsewhere. But it- but it- it was just … you know, I mean, I rejected the conventions that I’d grown up with, like everybody does when they’re an adolescent. And part of the rejection was the enjoyment I got out of pointing out to my friends these outrageous things.

PAUL JAY:So, I mean, did you grow up in your own mind as sort of a believer, and then you get disenchanted, and then become a believer again?

BRUCE COCKBURN: No, I grew up as a kind of bystander. And when I got into that part of it I became an interested bystander. But it wasn’t till kind of in my mid-teens that I began to have a sense that there was a spiritual element to life that should be paid attention to. It had nothing- well, it had no direct relationship that I recognized between the Christian teachings I was given as a kid and that sentiment. But I, maybe there- I mean, it’s hard not to think that there was some connection. But I wasn’t aware of it. And so, you know, it was more from reading beat writers, reading about Buddhism and stuff, and you think, well, these guys are really interesting guys, and they’re talking about this stuff that- I started paying attention to that.

[Clip of One Of the Best Ones – Bruce Cockburn]

And you know, the word ‘existentialist’ got tossed around in those circles, so I started reading existentialist philosophers and I, you know.

So I’m wading through Martin Buber, and I’m reading, you know, for fun I’m reading Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac. And it really started with that. And then- things move fast at that age. There is- when I look back at it I think, in a given year, so many things happened. Like, nowadays it seems like- it’s partly the internet culture, but mostly it’s just age- that everything happens fast. So I look at a year, and like, what happened in that year? Oh yeah, Iona was born in that year. Well, you know.

PAUL JAY: Iona is your- your daughter.

BRUCE COCKBURN: My 6-year-old.

PAUL JAY: 6-year-old.

BRUCE COCKBURN: So. You know, that- I mean, I can look at events. But when I look back at what happened the year I was 18 or 19, there’s all these things that happened. It seems like- like how could all that stuff have happened in only one year? So what I’m- why I’m saying that is that somewhere in that very few years, that two or three years of teenhood, and late- the second half of being a teen- I discovered the idea of spirituality. And I went through a whole lot of angles of approach to that, from rudimentary- I mean, I never became a Buddhist, but I paid attention to Buddhist stuff and I read Buddhist literature and I, and I- I read Alan Watts, and I- and the beat writers. And I took it seriously. And I read these philosophers, and I took that seriously. And I got into a kind of flirtation with the occult, and I took that seriously. And all of this was about finding out what spiritual reality might be, and if- and how I should relate to it.

I’m still, you know, working on that. But it’s a bit clearer now than it was then. So I went through all these- all these different things. And it’s not like I looked at Buddhism and then put that away. They synthesized. So my understanding of spirituality was shaped by exposure to all these things. And you know, that’s- the book talks a lot about that.

[Clip of Night Train – Bruce Cockburn]

PAUL JAY: Please join us for a continuation of our series of interviews on Reality Asserts Itself with Bruce Cockburn.

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter

“Bruce Douglas Cockburn OC is a Canadian singer-songwriter and guitarist. His song styles range from folk to jazz-influenced rock, and his lyrics cover a broad range of topics including human rights, environmental issues, politics, and Christianity.”