On Reality Asserts Itself, Mr. Pollin says there’s no evidence technology will make fossil fuel clean, and it’s more cost-effective to achieve energy efficiency and produce alternative energy.

This is an episode of Reality Asserts Itself, produced January 9, 2015.

STORY TRANSCRIPT

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to The Real News Network and welcome back to Reality Asserts Itself. We’re continuing our series with Bob Pollin from PERI institute on how we get to a green economy. And he joins us again in the studio. Thanks for joining us.

PROF. ROBERT POLLIN, PERI CODIRECTOR: Thanks, Paul.

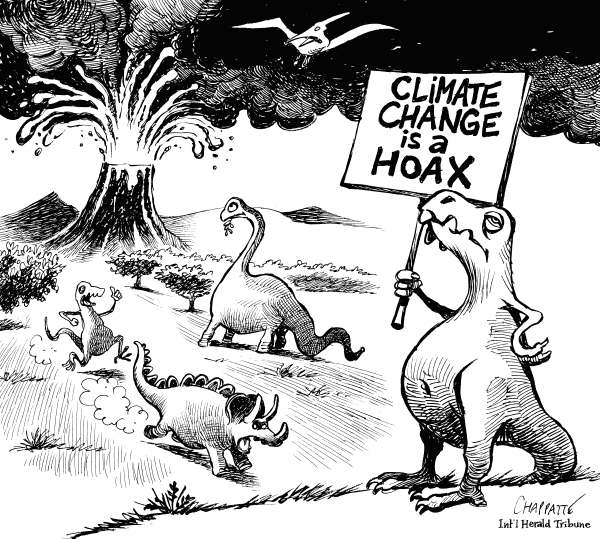

JAY: So I’ve done this introduction. You really should watch all the various segments. But Bob is codirector of the PERI institute in Amherst at the University of Massachusetts. And he’s got a new big–two big reports on how to go green. One’s called global green growth, and he did that with the United Nations. So watch the other segments and you’ll know how we got here. We’re going to talk this time about some other options. And one of the biggest option–let’s back up. One of the biggest problems in terms of carbon emissions in the United States–many scientists have said this–is coal. And Jim Hansen and others have said, if you’re going to start anywhere, start on coal and reduce the use of coal, get to zero, phase it out, but coal should be our first target. The coal industry’s answer to that–and President Obama, to a large extent, has echoed this, even though he’s introduced some regulations to diminish coal use in the United States–is there such a thing as clean coal? And we will get there. So what do you make of that? What’s wrong with clean coal?

POLLIN: Well, okay. Clean coal means using this technology called carbon capture and storage, which literally captures the carbon emissions as they get generated by burning coal. And then there’s a transportation system with the carbon which figures out a way to move the captured carbon and store it underground permanently. That’s basically the idea.

JAY: So we’re talking about, like, big electrical stations that use coal to generate electricity, that use massive amounts of coal. And what? They would use scrubbers of some kind and–.

POLLIN: Not scrubbers. They’d capture–there would be equipment that would literally capture the carbon and then store it. Maybe you would liquefy it so you could move it and then store it underground permanently. That’s the idea.

JAY: So President Obama’s looked at this, and he seems to think this is legitimate science and it’s going to happen.

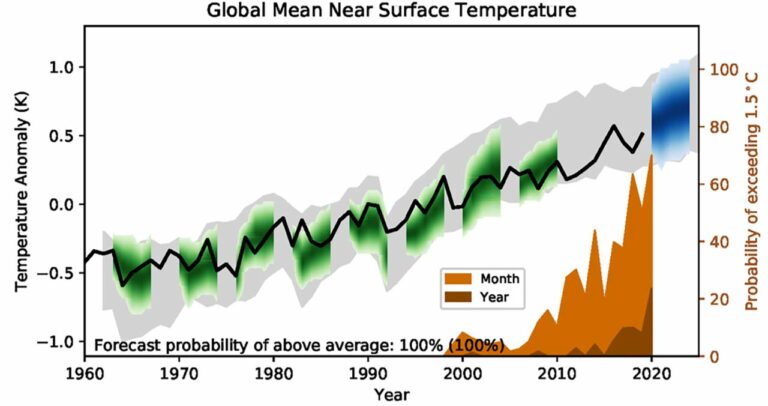

POLLIN: Okay. So what are some of the problems? Well, the simplest one is it’s very expensive. So if we are talking about renewable energy of solar, wind, geothermal as being expensive, if you were to introduce the carbon capture and storage technology, that would be much more expensive than any of these other renewable energy options. Number two, there is no evidence that we can get this built at commercial scale. And you said, yes, coal is a massive–this massive resource. Oil and coal are basically the same, globally, in terms of consumption. If there was really an easy way to do carbon capture and storage, it probably would have been done by now. But the fact is we haven’t got a single carbon capture and storage operation anywhere in the world after this has been talked about for decades. And third, what about this storage? Where are we going to store it? I mean, when you talk about capturing that CO2, maybe liquefying it, and storing it, you’re talking about an energy infrastructure that is as big as the entire oil infrastructure that we already have that pulls oil up from the ground, transports it, refines it, and so forth. You’re talking about something at that level of magnitude. We’re not going to get there in 20 years. We’re not going to–who knows if we can ever get there? So if we want to talk about things that are realistic, actually the more conservative route is invest in–spend the trillion dollars on energy efficiency, spend the trillion dollars on getting solar widely and cheaply available. So that’s what’s wrong with carbon capture. Now, of course, the reason why the coal industry likes it is because it keeps coal alive. But coal doesn’t have a future.

JAY: And it makes people think there’s not a problem. You see these endless amounts of television advertisements about clean coal–clean coal’s coming, we’re working on clean coal. I mean you get the impression it’s here.

POLLIN: It’s not here. There is no commercial operation, commercial-sized operation anywhere. And, again, if it could have happened, it would have happened by now.

JAY: Okay. The other question or argument is, well, what about nuclear? That’s another way to deal with this. Instead of so much effort on fossil fuel, develop nuclear energy and slowly start replacing fossil fuel with nuclear.

POLLIN: Okay. So–.

JAY: And even some environmentalists have been antinuclear for a long time. People like George Monbiot and others have been saying, well, maybe we’d better look at this, because the situation’s so urgent that it’s worth the risk.

POLLIN: Well, if there were no alternative, if energy efficiency and renewable were not viable alternatives, as I am convinced they are, then I would say, yes, then maybe we need to start thinking about nuclear. Nuclear power supplies about 5 percent of global energy supply now.

JAY: Now, the counterargument to you–and I can’t–don’t have the numbers at hand, but the counterargument I always hear is that the window for alternative energy actually being able to replace fossil fuel is much longer than 20 years.

POLLIN: Well, I don’t agree with that. And as I’ve been saying in the other segments, if you actually do the investments at roughly one and a half percent a year of each country’s GDP, we can build out a renewable energy sector and raise efficiency such that you can hit the emission reduction target.

JAY: That’s the point. When you hear these arguments, they don’t usually add to that, trying to get to zero efficiency–what is that?–zero energy loss buildings.

POLLIN: Net zero.

JAY: If you have such highly efficient buildings, then alternative energy [crosstalk]

POLLIN: That’s right. That’s right. And nuclear power is at 5 percent of global energy supply now. If we’re talking about increasing it five-, ten-, 20-, 30-, 40-fold, I mean, all the problems that exist with nuclear–radioactive wastes, the storage problem, the problem of proliferation–I mean, this was a big issue that–I mean, what if nuclear energy gets in the wrong hands? And it only has to happen once. We don’t have to deal with probabilities. Maybe there’s a small chance that somebody who knows how to deal with nuclear energy is able to use that nuclear energy and convert it to weapons. But what if it only happens once?

JAY: You know, it’s interesting. We were talking off-camera about the FEMA regulations. And if you’re in a FEMA floodplain, which we are in Baltimore, if there is a 1 percent chance in 100 years that you could have an eight foot–hit the height of the floodplain in our–where we are it’s, like, eight feet–they are making you do tremendous investment in flood proofing.

POLLIN: Good analogy.

JAY: And it’s a tiny, tiny percentage, but it’s enough to force you to completely flood proof your buildings. And many buildings in Baltimore now, new construction, are having to entertain massive costs on this. Well, you would think it’s 1 percent in 100 years you could get a nuclear accident.

POLLIN: Way more than that. I mean, look at what happened with Fukushima. Now, people have criticized the nuclear accident in 2011 in Fukushima, Japan, because they said, oh, the regulations weren’t good enough. It was this tsunami that set off the nuclear meltdown of the plant. Well, both things are true. But first of all, as you said, that kind of climate event is happening more frequently. And then, secondly, you could say, well, okay, the regulations weren’t that good at Fukushima in Japan. But Japan has the best regulations in the world. I mean, of all countries, the one country that has suffered the most as a consequencee of nuclear energy, if they can’t regulate adequately their nuclear energy system, do we really think that other countries are going to do it a lot better? I don’t think so. And look at–what’s happened in Fukushima is that even two and a half years later–the accident was in March 2011–by August 2013, the nuclear regulatory agency in Japan has said that we have underestimated the extent to which there has been water contamination resulting from the accident. So, again, we don’t really know the full extent of the health risks at Fukushima. Now, again, multiply that 40-fold. We are facing a very unsafe situation, and we’re just inviting the kinds of disasters that nuclear power can bring. Now, again, if that was the only alternative, maybe. But it is not the only alternative.

JAY: So you’re a why entertain any risk if there’s an alternative.

POLLIN: Right.

JAY: And that’s the one we’ve been talking about.

POLLIN: Right.

JAY: Okay. In the next segment of our series, we’re going to talk about some people are proposing zero economic growth is really the only solution. This idea of building a green economy and still continuing to grow GDP is an illusion, they say. You can’t really get to the necessary targets through growth. You’ve just–the only way to really cut carbon emissions is stop growing. And that’s what we’re going to take up next on Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network.