On Reality Asserts Itself, Mr. Pollin says Germany runs its economy at twice the energy efficiency as the U.S.

This is an episode of Reality Asserts Itself, produced January 8, 2015.

STORY TRANSCRIPT

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay, and we’re continuing our series about how do we get to a green economy with Bob Pollin. Thanks for joining us, Bob. So, one more time, Bob is codirector, distinguished professor of economics at the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. And he is the author of two reports on going green. One’s called global green growth, a forthcoming report with the United Nations [Industrial] Development Organization. So we’ve been talking about why we need to and what it might look like. And watch the first segments and you’ll know why and what. But now we’re going to talk about what can we learn from other countries. So, first of all talk about some positive examples. Are there models in the world that could be applied in North America that make some sense?

PROF. ROBERT POLLIN, PERI CODIRECTOR: There’s a lot of positive evidence from other countries. We can start with Germany. So Germany is a country that is roughly at the U.S. living standard. So they’re not sacrificing anything.

JAY: On the whole, probably a little–in many ways higher. But go on.

POLLIN: Well, you know, roughly at the same. In terms of what we talked about in the last segment on energy efficiency, they’re running their economy twice as efficiently as the United States. So this notion that it’s really hard for us to achieve efficiency gains is completely contradicted by the fact that Germany is running their economy today at twice the efficiency level of the United States.

JAY: And have they sacrificed anything in terms of productivity?

POLLIN: No. I mean, they’re running an economy at per capita GDP the same as us, as a higher level of average productivity growth that is much more successful in terms of–.

JAY: So how’d they get there?

POLLIN: Well, they’re committed around issues of starting again with energy efficiency. So you can operate the U.S. economy tomorrow at the German level of efficiency if we made the investments. Their buildings are way more efficient, their cars are way more efficient, they use a lot more public transportation, and their machinery is more efficient, because they think about it. Now, not only that, because one of the arguments as well, how could we ever get to the German level, well, not only are they twice as efficient now, but their plan for 20 years is they’re going to double their level of efficiency over the next 20 years.

JAY: So what’s the big difference? Why was Germany able to do it and not here? POLLIN: Two big things. One, they’ve had a Green Party for 40 years. And I don’t necessarily agree with everything the Green Party’s done, but they have been successful. I mean, when they got first elected in the 1970s, they were a bunch of crazy hippies. That’s how they were perceived. But they were in the Bundestag, they were part of the political process, and they won. And they–well, I don’t know the vote they get. It ranges–10, 15 percent. But they have power. And that has forced the mainstream parties–no matter which mainstream party is in power, they do not openly defy the Green Party. And number two, they don’t have any oil. JAY: No big oil companies.

POLLIN: They don’t–they’re there, but they’re not based–and Germany doesn’t have the resources. So you don’t have that resistance from the fossil fuel industry that you do in the United States. I would say those are the two big factors.

JAY: Yeah. Well, in some ways, maybe the second even the most prominent, although I wouldn’t underrate the first. But they don’t have the Koch brothers and all the others like the Koch brothers actively fighting any kind of legislation.

POLLIN: That’s right.

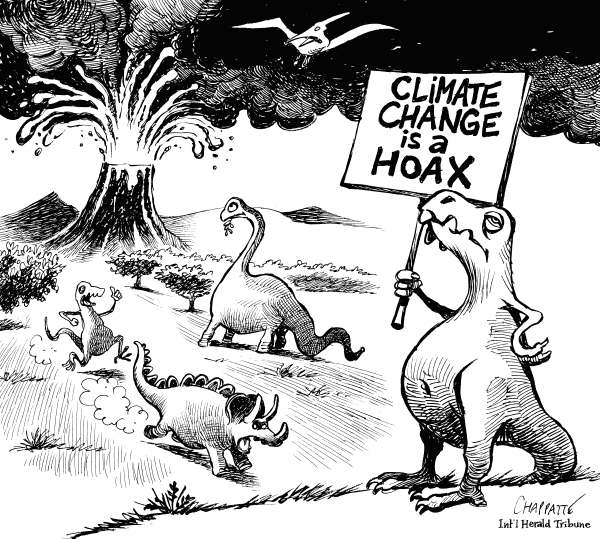

JAY: And I assume the preponderance of Germans believe there actually is such a thing as climate change.

POLLIN: Well, if you talk to–you know, anecdotally, as I’ve done, if you talk to Germans, and if they say, you know what, it’s going to cost us $1,000 a year to do this, which I don’t necessarily think is true–and we get into that–but they say, so what if it costs us $1,000 a year? We’re a rich country on average. We can afford $1,000 a year. I mean, there is a rural town in Germany whose name I can’t remember right now. They are operating on 100 percent green energy. And it wasn’t because they were ultra-greens. It was because they figured out, by operating at high efficiency and relying on wind power, in their case primarily wind power, they could do everything they wanted, and they didn’t have to spend a lot on bringing oil and bringing utility-based electricity into the community.

JAY: What are some other global examples?

POLLIN: Brazil is another. Brazil is a great example. If we talk about the global situation, right now, globally, on average, every person emits or generates 4.6 tons of CO2 per year. Now, of course, there’s massive differences, but on average it’s 4.6.

JAY: Yeah, it’s because if you live in the United States, you’re doing a heck of a lot more than–.

POLLIN: Now, the United States is 18. Okay? But, anyway, the average is 4.6. Brazil is at 2.4.

JAY: Highly industrialized country.

POLLIN: And it’s a growing industrialized country. Now, they have big advantages, in that they have a lot of hydro resources and they utilize hydroelectric power. That’s a big part of it. But they also are running an economy at a much higher level of efficiency than the United States or other newly industrialized–.

JAY: For example?

POLLIN: Okay. So let’s take another example. South Africa.

JAY: No, stay with Brazil. What are they doing that’s more efficient?

POLLIN: Oh. Well, the efficiency is not, like, any big deal. You have more efficient buildings, you have a more efficient transportation system, you have smaller cars, and you have more public transportation. That’s all there is to it.

JAY: I mean, and it would be relatively simple to put it in the building code. I mean, you have one thing is retrofitting, but there’s very–I don’t know if there’s anything in the building code that’s actually–assists on efficiency, is there? I mean, not where we are.

POLLIN: Well, there are. For public buildings now–.

JAY: No, I mean for private buildings.

POLLIN: No. I mean, of course it varies by community, but the basic answer is–.

JAY: In California I think there is for public buildings. Is it national?

POLLIN: Well, public buildings, yes. In the U.S. now we do have standards. We are getting to more efficient buildings, but not efficient enough. Like I said, Germany’s standard is zero emissions. And we can get there. Like I said, I myself am involved in putting up a building now in Amherst, Massachusetts, that will be zero. There’s no reason why every new building can’t be there. Yes, we have to think more, we have to spend more up front, but we’re going to make it back within a couple of years.

JAY: And, of course, if everybody does it, it gets a lot cheaper to do.

POLLIN: Yeah, and then it just becomes part of common conventional wisdom how you put up a building.

JAY: So South Africa.

POLLIN: South Africa is really bad. South Africa is extremely inefficient, and they are very high emissions because they rely on coal. They’re a big coal exporter. They consume coal. Coal is the most dirty burning fossil fuel. Oil and natural gas are cleaner–they’re not clean, but they’re cleaner. So if you compare Brazil and South Africa, where, in those two countries, the per capita per person GDP is roughly the same, Brazil on average is–the average Brazilian is emitting 2.4 tons per year; in South Africa, it’s more like 14.

JAY: And this is public policy is the difference.

POLLIN: Well, it is resources. I mean, you know, like I said–.

JAY: Hydroelectric.

POLLIN: Hydro is big. But hydro can–small-scale hydro has a lot of promise. And people think hydro is a disaster ’cause you put up these massive dams, you displace hundreds of thousands of people. That’s not the only way you can do hydro. You can do smaller-scale hydro. There’s, for example, a lot of opportunity in India. Indian small-scale hydro could be a major new resource. And renewable energy on average–so we’re talking about hydro, solar, wind, geothermal, and clean bioenergy–their costs are now at close to parity with fossil fuels. Solar is not. But the others, on average you can put them up and run them, and nobody’s sacrificing anything in terms of the costs.

JAY: Now, if you’re talking globally, the other country that kind of really matters is China. What’s going on?

POLLIN: Okay. So China and the U.S. made this deal, you know, what, two weeks ago, that China promises that by 2030 they’re going to cap their emissions. That is progress. But that’s not nearly enough. The U.S. and China are responsible for 40 percent of all emissions, okay? So, yes, the rest of the world we’ve got to cover, ’cause that’s 60 percent. But the U.S. and China, both have to reduce their emissions by 40 percent within 20 years. And so it’s–China’s saying they’re going to cap in 20 years. So that’s not close to adequate. So China has to do–it’s the same thing: invest a percent and half of GDP per year in clean energy. In fact, China is investing significantly in clean energy, but they’re exporting all the solar panels. They aren’t keeping them in China.

JAY: Yeah, they’re, like, one of the world’s leader in the creation of solar panels.

POLLIN: Yeah, but they need to build it out in China. And in developing countries, in China, in India, in Indonesia, in South Africa, in Brazil, the other factor is investing in clean energy is a big source of jobs. And the answer here again is very simple. It’s because if you spend on the clean, green energy economy, it requires more people, and there’s more domestic investment than if you rely on fossil fuels.

JAY: But the other side of this, as you mentioned in the earlier segment: you can’t just make buildings more efficient and start using alternative energy; you have to start reducing the use of carbon-based fuels. And China’s arguing that for the foreseeable–you know, that 20, 25 years or whatever, you know, you guys have had, like, more than 100 years of industrial development, and you’re profiting from it, and you’re eating up the resources of the planet, and you have the highest standard of living.

POLLIN: Yes, true, true, true, true, true.

JAY: And now you’re telling us we have to get off fossil fuel–

POLLIN: True, true, true.

JAY: –before we get there.

POLLIN: Yes. That’s true. And it’s not fair. So we have to think of some standards of fairness that reflect the magnitude of the problem of climate change, again, if we take climate science seriously. So here’s another example. Indonesia. So Indonesia we’re talking about levels of emissions per person. Indonesia is at 1.7 tons per year per person. Again, the United States is at 18. China’s at about six. Well, Indonesia’s–they’re saying, well, we want to grow like China, and you can’t stop us, that’s not fair, because their standard of living is one-tenth or one-12th of the United States’. And, yeah, by that measure of fairness, they’re right.

JAY: And this is the fight that keeps taking place at all the international meetings is you rich countries have to subsidize this or we can’t do it.

POLLIN: Right. But even–so take the case of Indonesia. If they grow as they intend to grow over the next 20 years, their emissions per person is going to go up sixfold. And then you take the Indonesian case and you spread it throughout Asia, again we have no chance whatsoever of stabilizing the climate. So Indonesia also has to invest a percent and a half of GDP per year. Indonesia has massive resources of–.

JAY: And start reducing their carbon use. It’s not just the investment [side. (?)]

POLLIN: All them.

JAY: And they’re saying their development’s going to slow down if–

POLLIN: It won’t slow down.

JAY: –they start reducing the carbon side.

POLLIN: No, because the only reason it would slow down is if it costs more or if you literally have–you’re short of resources.

JAY: Because as you invest in the alternative energy side, you don’t need so much carbon.

POLLIN: I’m not going to say cut coal today. I’m going to say over 20 years cut it by 40 percent. And as that happens, you substitute green energy and efficiency. And when you do that, the green energy is not going to cost more. It’s at rough cost parity, other than solar, and solar is coming down very, very quickly. And so over the next 20 years, solar will be at cost parity with fossil fuel too. So there’s no reason to sacrifice. And on the jobs front, again, Indonesia, like China, would be a massive source of net job creation after allowing that the fossil fuel industry is going to contract by 40 percent.

JAY: So they’ve heard all these arguments.

POLLIN: I don’t think they have. That’s why I’m on your show.

JAY: Alright. Well, maybe they’re watching.

POLLIN: Yeah.

JAY: Okay. We’re going to pick this up. On the next segment, we’re going to talk about, well, there’s an alternative to what Bob’s saying, and that’s go nuclear, in terms of energy production, and to carbon-capture–this carbon stuff can be solved; it doesn’t have to be so dirty. So we’re going to see what he thinks of all that. Please join us for the continuation of Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network.