Israel struck Iran — but could this war set off something far more dangerous?

Middle East scholar Nader Hashemi joins Paul Jay to break down what’s really behind the so-called ’12-Day War.’ Far from a clean victory, Hashemi warns the strikes have likely strengthened Iran’s hardliners, accelerated the push toward nuclear weapons, and crushed the country’s democratic opposition. But this may not be a simple case of Western overreach — it may reflect a deep strategic split between the U.S. and Israel.

As Jay argues, Trump may be seeking to normalize relations with Iran, not to promote democracy, but to pry Tehran away from China and regain leverage in the great power rivalry — especially with most of Iran’s oil flowing to Beijing. Israel, on the other hand, appears willing to risk regional chaos to achieve regime change and eliminate its last major regional adversary.

What’s lost in the Western media narrative is the reality that the Iranian people — not the regime — are paying the price. And what’s collapsing before our eyes is not just diplomacy but the very idea of a rules-based international order.

This war may be just beginning — and its consequences could reshape the global balance of power.

Paul Jay

Hi, I’m Paul Jay. Welcome to theAnalysis.news. In just a few seconds, I’ll be back with my guest, Nader Hashemi. We’re going to, of course, discuss Iran and the war between Israel, Iran, and the United States, what Trump wants us to call the ’12-day war.’ That’s because history always starts from wherever Donald Trump says it does. Be back in just a few seconds.

So, joining me now to discuss the war against Iran is Nader Hashemi. He’s an associate professor of Middle East Studies and Islamic politics and Director of the Alwaleed Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding at the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University. Thanks for joining us, Nader.

Nader Hashemi

Good to be with you, Paul.

Paul Jay

Nader, the ceasefire is on. Trump is doing victory laps, supposedly, at the NATO meetings. To some extent, in my opinion, it is somewhat of a win for Trump for now. I don’t know how long any of this lasts. It also does seem a bit of a win for Israel if you look at the world through their eyes. Although, the Supreme Leader in Iran declared victory. Who should be declaring victory in your mind? What’s your take on the whole situation?

Nader Hashemi

Yeah, I can understand why Trump and Netanyahu are taking a victory lap. I think clearly, if one looks at who came out better on the other side, it’s the Israeli and the Americans. Iran, in many ways, revealed itself to be a paper tiger in terms of its military preparedness. It was completely taken aback by this attack. Most of Iran’s senior military leaders were assassinated, and many of its top nuclear scientists. Iran didn’t even have an air defense system that could protect its own skies. The Israelis and the Americans had almost complete access. Much of Iran’s nuclear program has sustained serious hits. We don’t know how big of a hit it is.

There are reports saying that the American strikes on the nuclear facilities have been very limited. It’s only pushed it back a few months. I just saw a report from the head of the International Atomic Energy Association, a man by the name of Rafael Grossi, saying that, no, the damage is actually quite significant.

At least in the short term, it looks like Iran now is a much weaker state in terms of its overall military potential and that they sustained a major hit. But, I think what’s going to happen from this moment is a series of events that have been now unleashed that there’s no stopping. And that’s going to, I think, fundamentally undermine the American and Israeli position. I’m speaking specifically about the predictable response from the Iranian regime now is going to fast-track and incentivize them to prepare and obtain a nuclear weapon. They’re going to make the case that look, that’s the only way we can protect our national security. That’s the major takeaway. They’ll have a lot of public support to do so because there’s a perception, at least among many Iranians, even those who despise the regime, that their national territorial integrity and independence have been severely jeopardized by these series of events over the last 10 days. So that’s not a net gain for Israel or the United States.

Also, the talk of regime change, I think if one looks at it, has actually emboldened the Iranian regime. Clearly, in my view, as someone who studied internal Iranian politics very closely, it’s actually weakened the internal prospects for democracy and human rights from within the human rights community in Iran. That’s not a net gain for the Americans and the Israelis.

Finally, the point that I think is one of the big takeaways is the biggest loser here is international law and what’s left of the so-called rules-based-

Paul Jay

That was my next question.

Nader Hashemi

Yeah, rules-based order, because now it’s just a laughing joke. I mean, it always was on tenterhooks with US policy in Gaza and European policy with respect to the horror show in Gaza, the contrast between Gaza and Ukraine. But if three weeks from now or a month from now, China decides to invade and occupy Taiwan, claiming they are posing a national security threat, the West doesn’t have a moral leg to stand on.

So, in many ways, we are in this new Hobbesian world, the rule of the jungle, where the UN charter, the rules of the international system that countries, such as Canada, at least theoretically, used to pay lip service to, no longer really exist. And you saw that most dramatically when, even at the G7 summit, the European countries, including the Canadian government, effectively adopted a position that was strongly supportive of the Israeli military attack on Iran, blaming Iran effectively for this crisis and saying things that were just completely ridiculous that Iran had to return to the negotiating table when they were at the negotiating table and the Israelis blew it up. So I think the long-term repercussions of this do not bode well for American and Israeli interests, and certainly not for the interests of those of us who believe in a more just and equitable rules-based order.

Paul Jay

Yeah, I think it’s important to say that there are no good guys on any side of this if you’re talking about the government ruling circle level, and that includes the Iranians. But what the Israelis have done in terms of crimes against humanity and what the United States has done, which even surpasses the Israelis, and of course, the Israelis couldn’t have done what they did in Gaza or in Lebanon without the United States. But whatever crimes the Iranian state has committed, and it certainly has, they don’t come close to the crimes of the Israelis in the United States. So there’s no good guys here.

The way the media covers this, it’s all about state versus state. It’s ruling circles versus ruling regimes. The people who have been attacked here are the Iranian people. One of the principles of international law is not collective punishment, but that’s exactly what’s going on here. They don’t like what Iran did in terms of supporting Hamas and Hezbollah, but it’s the Iranian people who are paying the price. So, dig into more of this whole issue in terms of international law. What’s at stake here?

Nader Hashemi

Yeah, I completely agree with that characterization; both the Iranian regime and the Israelis are nasty regimes. The old argument used to be that, well, Israel, even though it has a massive nuclear arsenal, could be trusted to behave in a responsible way because the nature of that regime was not as draconian and as horrific as its adversaries. But now, if you just compare the human rights record of the Islamic Republic with the human rights record of the state of Israel, there’s not a lot to admire there. I mean, now we’re talking about a Netanyahu government that is widely viewed around the world by the human rights community as presiding over an Apartheid state. Now, it’s a genocidal state. It has nuclear weapons. It has the support of many Western governments. The Iranian regime is brutal, authoritarian, and repressive; it executes more people than any other country in the world after China, and they’re told that they can’t have a nuclear weapon. So when you look at it from a human rights perspective, there’s not a lot there to admire on either side.

When it comes to international law, it’s clear that what we’re seeing here is we’re being exposed to, I think, a great teaching moment in terms of how international law is selectively invoked by great powers when it serves their interests, and they just throw it away when it doesn’t serve their interest. This gung-ho support from the European Union from Canada in support of this Israeli attack on Iran, which was a clear violation of the UN Charter, the rules of the international system, clearly an act of aggression based on concocted evidence that no one believes existed in terms of Iran about to have a nuclear weapon, thus necessitating an Israeli strike.

All of those arguments and principles that we saw that the West invoked so passionately when it came to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, claiming that we had to stand up for this rules-based order. We had to condemn aggression. We had to oppose the occupation. We had to go after war criminals. And then, Gaza happens, and all of those principles are tested. And the same countries who are speaking with such robust certainty about the sanctity of international law, throw those principles away when it comes to the Palestinians. And then again, in the context of Iran. So what it does is it actually creates a big fissure. It widens the chasm between the global north and the global south. In North America, what I’m talking about doesn’t resonate in terms of mainstream media analysis. There’s just an assumption that look, the Middle East is ours, and we’re going to support our friends, and we’re going to go after our adversaries.

Some countries in the Middle East can have nuclear weapons; in other words, our allies and our adversaries can’t. And if they try to do it, we’re going to bomb them. And that’s the way the system works. But in the global south, people see the hypocrisy, see the double standards, see how this looks like and smacks of another 19th-century imperialist moment, where the West and its allies are just going to use their military muscle to impose their will on parts of the world that they view as an adversary.

And so I think fundamentally, what’s happening today, and I wrote about this in my Guardian piece a few days ago, the fundamental reason why I think the bombing of Iran happened is because Iran in the Middle East represents a country that has an independent foreign policy separate from the great powers. And when I mean it’s an independent foreign policy, I don’t mean it’s a good foreign policy, but it’s separate. It works outside of the orbit of Western interests. And it has challenged American and Israeli interests in the region. And now, Iran is very weak because of its losses in Lebanon, primarily, and in Syria. And now there’s a sense that we can take this regime down if we just hit it hard enough.

I think that fundamentally explains the why now question. There’s a sense of having defeated Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in Lebanon. And now that the Mossad regime is gone, if Israel were to just now expand its reach and defeat its one regional adversary, it could establish full hegemony over the Middle East. The West, of course, has backed that. That works with Western interests. And so that explains, I think, why the West is behaving in this way with respect to this conflict. And also explains the double standards that we’re seeing.

Paul Jay

So I think most of our viewers know what I’m about to say, but I’m going to say it anyway, just because it needs to get said. In mainstream media, you don’t hear what we’re talking about very often. The only reason Iran doesn’t have “a right to enrich uranium” at almost nuclear weapon levels, the only reason Iran doesn’t have right to build a nuclear bomb is because it signed the Nonproliferation Agreement and said it wouldn’t. Otherwise, it has every right as much as Israel, the United States, or any other country to have a nuclear weapon. So the way this whole thing gets reported on is somehow there’s some underlying reason in terms of international law, other than a treaty that Iran voluntarily signed and can voluntarily leave anytime they want, and have chosen not to.

Number two, there was no imminent threat. They didn’t have a nuclear weapon. Nobody, neither Israel nor Trump, is saying they’ve got one, and they more or less admit it isn’t imminent in the way within weeks or days or something; they try to say that, but everyone knows it’s nonsense. Under international law, if the threat isn’t imminent, you’ve got no right to a preemptive strike. Even on CNN, you can hear people say there was no right under international law, nor was there, even in terms of American law, a right to declare war without an act of Congress.

Okay, all that being said, and let me just even say again, the criminal Israeli regime, because if we’re going to call Iran a regime, I might as well call Israel one, too. We might as well say that about the United States, too. So, let’s call them all governments for now.

All that being said, why the heck was Iran enriching at 60%? Assuming they were. I don’t think they’ve denied it. I think it’s pretty well clear that they were. And it makes me think this is a bit like Saddam before the invasion of Iraq, where he was bluffing about having a nuclear weapons program. All the inspectors said he didn’t have one. Everyone who knew anything for real knew he didn’t have a nuclear plan or a biological weapons plan. All the UN inspectors were saying so. But for some insane bravado, Saddam was bluffing that he did. Why on Earth did he think that would work? it helped feed the argument of the Americans that there was some justification for the invasion. This almost feels something similar to me.

Why enrich at 60%? I see Marco Rubio on TV, and as much as I can’t stand Marco Rubio, and I can’t stand the Trump foreign policy, and so on, and so on, it’s not a bad question. Why are you enriching at 60%? Why are you shoving it in some mountain? If it’s really for making medical isotopes, which is the only possible reason to go beyond what, 4 or 5%, what’s needed for nuclear power, you don’t need all these shenanigans to make some isotopes.

Nader Hashemi

Right. It’s a great question. I think we need to just roll back the clock a bit and understand how this all evolved. Recall that in 2015, Iran struck a nuclear agreement with the West, principally the United States. It was called the JCPOA. It’s widely viewed as one of the most significant and comprehensive arms control agreements ever negotiated. The world effectively celebrated that event. There was talk of a Nobel Peace Prize for the Secretary of State, John Kerry, and his counterpart, Javad Zarif, the Iranian Foreign Minister. Iran put its nuclear program basically under international inspection and rolled everything back. Things were moving forward.

In 2018, Donald Trump tore up the agreement at the encouragement of Israel and its allies in Congress. And then Iran still, for one year later, adheres to the agreement, and then it starts to enrich uranium at 20%, then at 60%. It was doing that, I think, primarily as leverage to get sanctions lifted. That’s the key, I think, incentive and motive here. Iran had given up its whole enrichment program. Under the terms of the nuclear agreement of 2015, they agreed to keep it at very low levels for nuclear energy under 4%. So that, I think, is an answer to the Marco Rubio question: why are you doing this at 60%? And I think Elon was always trying to compromise.

Paul Jay

Okay, so let’s be clear. Supposedly, it gives them leverage in negotiations when, in reality, it seems to me it makes them a target.

Nader Hashemi

Yeah, well, that was the risk they were playing, right? Because their bluff was called, right? As Rubio pointed out, why are you doing this? You must be wanting a nuclear weapon. So that’s the only leverage they had. Iran doesn’t have many cards to play, but I think it was constantly using the threat that it’s going to keep enriching uranium. It’s going to get close to nuclear weapons-grade material, but it never really crossed that line. So it was playing a very risky game because I think it had very few cards to play.

I think the other element here is that Iran wanted to produce a nuclear weapons program. So it could be in a moment of crisis at a situation where it would be a nuclear threshold state, that if ever there was an existential threat to the regime, it would have the capacity and the infrastructure to quickly move toward a nuclear weapon as a last resort to save the regime in this case. I think that was very much the calculation, which explains why they’ve invested so heavily for such a long time in building this extensive nuclear program. They gave it up in 2015 because they had to in order to get a deal to have sanctions lifted. And then they started to go back to what they were planning when Trump tore up the agreement and started to impose heavy sanctions on Iran.

So, this is the game that the regime was playing. But now all of that is yesterday’s news. As I said earlier in our conversation, I think I think the proponents within Iran, the hardliners, are going to now make a very convincing case, and they’re going to have much more public support than they did before, that the recent attack leaves Iran with no other choice but to try and develop a nuclear weapon.

Paul Jay

But that’s going to be crazy. Now, the Americans and Israel will bomb Iran with impunity anytime they feel like it. If they get the slightest win, that there’s another nuclear program going on, they’ll be worse than it was before. I just don’t get the entire thing makes no sense to me. I think they did have a choice not to do it before. They claimed they didn’t want to do it. If you want to do it, then bloody do it. Get out of the nonproliferation agreement and go for it.

Nader Hashemi

Well, that’s what they’re doing. If you’re following the recent news, Iran’s parliament is very much of a rubber stamp parliament. They passed legislation to suspend their relationship with the International Atomic Energy Association. There’s talk of pulling out of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty.

I agree, it’s high risk. But I think the other option is to simply adhere to what Donald Trump has said, “explicitly, unconditional surrender,” to give up its nuclear program. For the Iranian regime and for segments of society, it’s a source of national pride. They’ve invested heavily in it. They make the arguments that we were just talking about a moment ago. Why can Israel have a nuclear weapons program? Why can Pakistan have a nuclear weapons program? Why can’t we?

This is going to be a big internal debate. I agree, it could invoke another military assault on their program. But I think one of the key lessons that this moment teaches countries, including Iran, is that if you don’t have a nuclear weapon, you’ll be subjected to this type of intimidation and bombing. Look at North Korea. North Korea had developed a nuclear program. They can’t touched in this way. Look what happened to Libya. Libya had a nuclear program. It gave it up because the West wanted it to give it up. When the moment of truth came, and the regime was about to fall, they had no cards to play.

In fact, there was a very famous statement that Iran’s Supreme Leader made at that time when Gaddafi was toppled. He basically said, I’m summarizing, but I remember it very well. He was saying, “You know, Muammar Gaddafi, you stupid idiot. Look what you did to yourself. You gave up your nuclear program because the West gave you these assurances. Now, in your moment of need, you have nothing to protect yourself.” So I think that’s going to be one of the big takeaways. And yes, it is high risk. It is stupid. But I think this is the big debate in Iran right now. There’s going to be a pushback.

Paul Jay

Let me say, yeah, well, I think it’s not high risk. I think it’s suicidal. But I think there’s a reason why it’s suicidal. And tell me if you think I’m right. Almost, I think, for every country, foreign policy starts with domestic politics. It’s been true for the United States. And it’s true, half of the Cold War had nothing to do with a real Soviet military threat, which they knew there wasn’t one. But it was part of the narrative of the anti-communist campaign and the campaign against Socialists, progressives, and trade unions in the United States. And it’s part of a narrative to impose a global hegemony of US capital.

But in Iran, the narrative is that this government, but I’ll say regime because we go beyond the government. It’s all the religious, political, Revolutionary Guard, and this whole architecture. Their raison d’être, their justification, is that they’re the defender of the faith. They’re the defender against the great Satan. They’re the defender against imperialism. They’re the leader of the resistance, as much as a lot of that is not true. But still, some of it, I guess, to some extent, as you said, they do have a foreign policy that the United States doesn’t like, and that’s a sin in American eyes.

But when I’m asking in terms of Iranian domestic politics, the class struggle in Iran, where there’s a very, very wealthy elite, and much of the country lives in poverty, and the working class is suppressed, and unions are illegalized, and women’s rights are suppressed, it’s a very sharp class struggle. I think it’s very similar to Israel.

I was at a film festival in Israel about 25 years ago or something. And someone told me that if it wasn’t for the Palestinian struggle- and at that time, there weren’t terrorist attacks going on at the time I was there, but it wasn’t that far back. What I was told was if there wasn’t an existential threat from the Palestine question, from the Palestinian struggle, there’d be civil war in Israel between the secular and the Orthodox. And it’s the same thing, the same issue in Iran. If Iran doesn’t have this existential threat of Israel and doesn’t have the existential threat of the West, how does class struggle in Iran evolve? Don’t they need this super enemy just as much as the Israelis do?

Nader Hashemi

No, I would agree with that framing, which is one reason why I was such a big proponent of the nuclear agreement in 2015 because it diminished the international hostility and context that enveloped Iran up until that point. It removed the threat of an external attack, which then created better internal conditions for the forces of democracy in Iran to coalesce themselves. Also, sanctions would be lifted, and that would give people purchasing power where they weren’t struggling to survive day, which would allow them to better mobilize. So that was my primary reason why I was so supportive of that nuclear agreement because it would have positive consequences within Iran for those progressive forces.

I don’t think the Iranian regime, obviously, benefits from this external context, but it’s also a risky game for them because they don’t want to push things to the point where there’s regime instability and the regime faces an external crisis, as we’ve just seen. So they’re playing a very careful game.

But I think what we’re seeing right now at this moment is this attack is allowing the regime to do several things: one, to have what’s called this rally around the flag effect, where people who, even if they hate the regime, they’re upset over how Israel has so brutally attacked Iran and killed mostly civilians. That’s point number one.

The regime is also using this national security crisis to round up people in the name of going after these Mossad agents and to silence any and all critics. I’m just reading reports today that there’s been six executions over the last couple of days. Prisoners are being moved around to create more room in prison. And that’s, I think, going to be an opportunity for the regime to say, “Look, we’re in full control now. Anyone who dissents on any of our policies, you’re going to wind up in jail.” So this is something we’ve seen before: when there’s a national security crisis, repressive regimes take full advantage to consolidate their control. So that’s playing itself out, and it’s going to have negative consequences and connotations for the Iranian people.

They don’t have a lot of choices. I think the Iranian people I often describe as caught between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand, they’re living under a brutal authoritarian regime that has a lot of repression and is willing to use a lot of bloodshed to stay in power. On the other side, they’re caught between the West and its sanctions and US foreign policy that really has never really, I think, been interested in supporting the forces of democracy in Iran. They’ve all been really interested in just containing Iran’s regional outreach, Iran’s challenge to America’s allies in the region, not really trying to take the question of democracy seriously. The prospects don’t look good for the Iranian people. They don’t have a lot of choices or options to work with as well. It’s a very dark picture. I’m very skeptical that this moment is going to, unlike what some people believe in the West, that regime collapse is imminent, and maybe if Israel just would have continued bombing a bit more, this would have led to the collapse of the regime. No, that’s not what’s going to happen. It’s going to actually have the opposite effect. It’s going to strengthen the regime and actually probably continue its shelf life because of the points that I just made.

Paul Jay

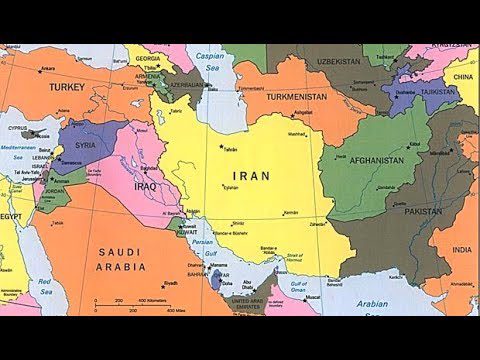

I’ll give you another possible way this goes. And I don’t know if this is Trump. He’s got some smart people around him. I think probably the biggest objective of the Americans right now is and should be, from the point of view of American imperialism, from their point of view, is to cry Iran away from China as much as they can. It’s very difficult because they put Iran in a situation that I think it’s 94 % of their oil goes to China. But if they can actually tell the Iranians, You can come back and do business again in the West. It’s an American interest to keep this class in power in two ways. Trump made an interesting comment on the airplane on his way to the NATO meetings. They said, Are you for regime change? And instead of saying, Well, it may happen, it may not. It’s not up to us. Someone talked to him, and he got the point. He said, No, because it will lead to chaos. And I think most people don’t understand how easy it would be for Iran to become what happened to Iraq. What is it? 30, 40 % of Iran, if I have my numbers right, is Suny, even if the majority is Shia.

There is so much opportunity for a brew of fishing in troubled waters of Civil War. If this government fell into the state of collapse, not because there was a movement ready to take over, but just falling into factions and fighting, it could be real chaos in terms of post-Saddam-Iraq. Am I right about that?

Nader Hashemi

No, you’re right. The figures of Sunni-Shia are a bit different than the ones you stated.

Paul Jay

Correct me, please.

Nader Hashemi

You’re actually absolutely accurate in terms of the possibility of the breakup of Iran, specifically along a more ethnic line. The United States would have, and they’ve already, I think, planned to pry the Kurdistan region out of Iran’s control. There has been a separatist movement among the Arab province of Khuzestan in the south, and also on the Pakistani border, the Baloch community has been persecuted and discriminated against.

If the central regime collapsed or was weakened, and I think there’s actually been discussion of this in right-wing circles in the United States and in Israel, this one way of pressing forward is to precisely try and weaken Iran that way. So these are very much options. Then it would lead to the type of chaos that you’re talking about that would make, I think, in many ways, Iraq look like a picnic because Iran is a much bigger state and has a greater population and huge refugee flows. I mean, even if 1% of Iran’s… even if 0.1 % of Iran’s 90 million people were to become refugees, that’s 900,000 people moving into Europe with huge destabilizing consequences. So, yes, things could get bad very quickly and have huge regional destabilization consequences.

Paul Jay

I don’t think the Israelis give a damn if that happens.

Nader Hashemi

Oh, I know. I think that’s very much their goal.

Paul Jay

It’s not good for the Americans. It’s not good for Europe, as you say. It’s not good for anybody, really.

Nader Hashemi

I agree. The thing about Trump [crosstalk 00:33:32]. Yeah, the thing about Trump, you’re right. What was so shocking about this attack and America’s support, Trump’s support for the Israeli attack was up until the day of the attack; Trump was actually talking about diplomacy. He was actually even saying things about the possibility of economic relations, and that was being reciprocated in Iran as well, that we could perhaps even see American companies coming and investing again, which is one reason why everyone was so shocked by the attack because everything seemed to be pointing in the direction of diplomacy and accommodation.

I think the problem here is that Trump is so inexperienced and seems to make big decisions based on the last person that he’s spoken to. It looks like he’s moving in one direction, then all of a sudden, he does the opposite. We’ve seen that in the last few days where, just recall what Trump said after the Americans bombed the nuclear facilities in Iran. He gave that statement in the White House with Rubio and Hegseth on his side, sounding really determined, praising Netanyahu, talking about how if Iran popped its head up again, we’re going to hit it hard. Then the next day, he’s criticizing Netanyahu and blaming Israel for not adhering to the ceasefire and talking about how we’re going to bring these two sides together, and how Iran fought really bravely. It’s almost as if he’s bipolar, this man. The tragedy here is that he’s the President of the most powerful country in the world. When he has that type of influence and impact, someone who’s so erratic and unpredictable, it has these types of destabilizing consequences. You literally don’t know what he’s going to do next.

Paul Jay

Well, I think he’s got two different voices. He’s got a little devil on this here. On this shoulder, he’s got another one here. Over here, he’s got the traditional neocon Cold Warrior mentality, which is that support for Israel is a key component of that Cold War style. Then he’s got the new Cold Warriors. The new Cold Warriors, it’s all about China. Anything you can do to weaken China because of the whole coming war with China.

You can imagine if someone wants to completely destabilize Iran, you get the Baloch, which is a big section of Pakistan that’s very persecuted. They have tons of resources, and they’re right near the big port that the Chinese have invested tons of money in. There’s a section of Baloch people that live on the Iranian side of the border, but they really are against the Chinese. There are all kinds of potential levers to create different fractions of civil war. Whereas if the Americans can get the Iranians to say, listen, you really are about… You want to make lots of money. You want to have some respect in the world. Well, how about you try it this way? We’ll let you back into the global economy. We’ll pry you away from China. You keep your theocracy. Look, we get along with the Saudis. We don’t care about theocratic dictatorship. We do very well with them. And allow the Iranians back in. And it seems to me if the theocracy in Iran can figure out a way to explain that to the Iranian people, maybe they go that route. And then maybe the Israelis really don’t like that because then you have a powerful opponent, even if it’s partly more in the Western camp, it’s still not going to be something Israel likes.

Nader Hashemi

Yeah. No, I would agree with that. That’s where the way things were headed. I think because of this crisis, it’s going to be very difficult for anyone in Iran, particularly among the senior hardline leadership, to make the case that we can trust the Americans again after what they’re going to perceive as a series of betrayals. Yeah, we can strike these deals and move in that direction. But how do we know Trump’s not going to pull out again and listen to the person, the analogy that you used, the voice on his right side, whispering in his ear? So that’s a new challenge that I think is going to have to be overcome. I don’t think it can be overcome that easily. We’re going to have to watch how all of this plays out, Paul.

Paul Jay

Okay, give me another final little sentence. Just a little message to Americans and Canadians, how they should think about this, and then we’ll wrap it up.

Nader Hashemi

Well, I think this is a very dark moment. I think this is a turning point for the politics of the Middle East. Yeah, Iran is weaker, and the United States and Israel seem to have won. But I think this war, ’12-day war,’ is going to unleash a series of unintended consequences that are not going to lead to regime stability or regional stability in the Middle East, but more instability as Iran tries to figure out what it wants to do with its nuclear program and how it wants to proceed in response to these events that we’re talking about. So I think this story is just beginning. It’s not by any way over.

Paul Jay

Great. Thanks very much for joining us, Nader. Thank you for joining us on theAnalysis.news. Don’t forget, there’s a donate button. We can’t do this without you. Most importantly, sign up for our email list because YouTube and some of the other platforms are clearly suppressing what we do. If you get on the email list, you’ll know what we’re up to. Thanks again.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | TuneIn | Deezer | RSS

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter

Nader Hashemi is Director of the Center for Middle East Studies and Associate Professor of Middle East and Islamic Politics at the University of Denver’s Josef Korbel School of International Studies. He is the author of Islam, Secularism, and Liberal Democracy: Toward a Democratic Theory for Muslim Societies.