Oppenheimer warned of a world with an unrestrained nuclear arms race on the edge of catastrophe. We are there, says Matt Korda of the Federation of American Scientists. Hosted by Paul Jay.

Oppenheimer: U.S. Developed First-Strike Weapon and Used Japan to Prove It – Kuznick and Jay

Paul Jay

Hi, welcome to theAnalysis.news. I’m Paul Jay, and we’ll be back in just a few seconds with Matt Korda to further analyze and discuss the film Oppenheimer. Please don’t forget we are only able to keep doing this because of all of you who have donated. If you’re somebody who’s regularly watching and has yet to donate, you can go over to the website and donate.

Last week, I published an interview with Peter Kuznik, the historian. We discussed Oppenheimer, the movie, and we discussed a few things that we thought were flawed in the movie, although it’s an incredibly great piece of filmmaking and, on the whole, a pretty good piece of history with some serious errors or flaws.

One of the most important, I guess, is while there’s a little bit of discussion that the atomic bombing of Japan wasn’t necessary militarily, the preponderance of the arguments in the film justifies the bombing as having saved American and even Japanese lives. There are other critical issues that could have been dealt with, we think better, and I suggest you watch the interview with Peter.

Now we’re going to talk a little bit more about what the Oppenheimer message was certainly after the war and what it means for today.

Now joining me is Matt Korda. He’s a senior research fellow at the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists, where he co-authors The Nuclear Notebook, an authoritative open-source estimate of global nuclear forces and trends. Matt’s also an associate researcher with the Weapons of Mass Destruction Program at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, SIPRI, and co-authors the nuclear weapons chapters for the annual SIPRI yearbook.

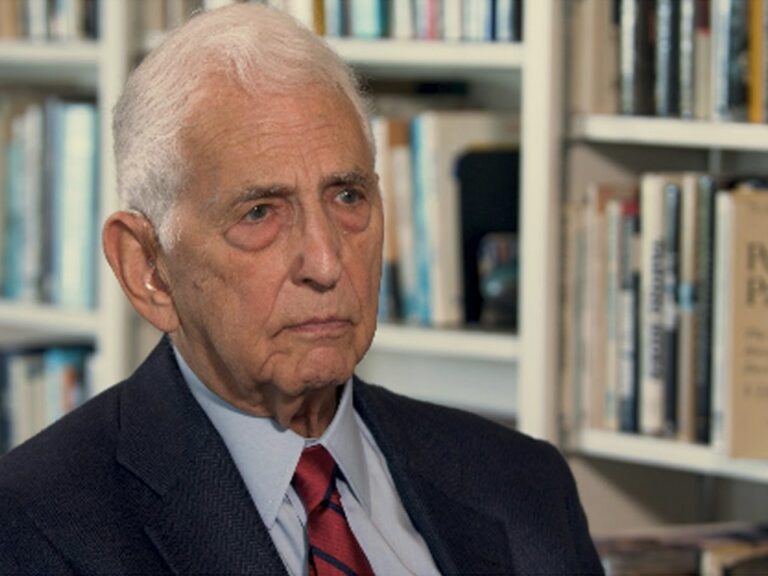

I should also mention that Matt is going to be in our film How to Stop a Nuclear War, based on Daniel Ellsberg’s book The Doomsday Machine. He’s also consulting with us on the film. Thanks for joining us, Matt.

Matt Korda

Thanks so much, Paul. Excited to be here.

Paul Jay

First of all, what’s your overall impression of the film, especially looking at it through the frame of the danger of today?

Matt Korda

Yeah, so a great quote that I thought really summed up my feelings about the film came from an interview that I saw with the historian Alex Wellerstein after the film was released. He basically said, “We’re living today in Oppenheimer’s worse nightmare,” which I thought really characterizes very accurately the state of global nuclear forces today.

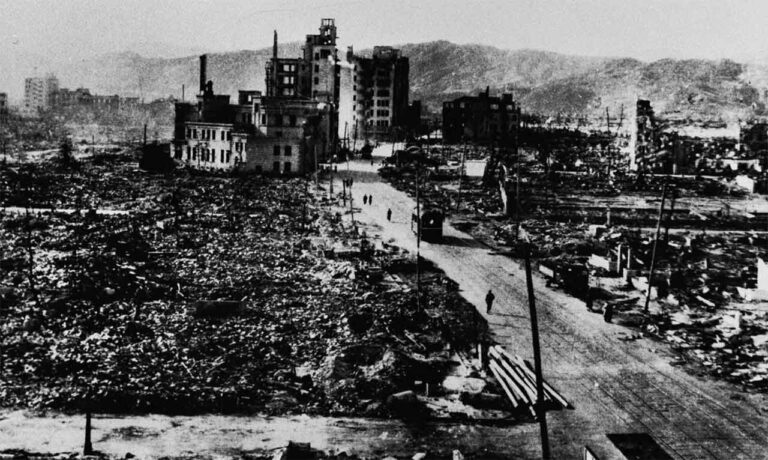

Back in 1945, when a lot of the film was taking place, you’re dealing with these weapons that are of a very different character than the ones today. The doctrines around which they would be used are very different. But today, there are really significant changes. One of which being that the number of countries that have nuclear weapons has grown substantially since the time of Oppenheimer. The number of weapons in the world has also grown quite significantly, and then the weapons themselves have become a lot more powerful.

Today you wrap all of these things up, and you position them at a time of pretty significant geopolitical tension, and you see that the last scenes of the film where Oppenheimer is talking about the state of the world and you see these images of the missiles flying and things like that; this is the world that we live in today, and that’s the really worrying thing.

Paul Jay

Oppenheimer supported the atomic bombing of Japan and even, to some extent, suppressed or didn’t push as much as he could have. Reports from his fellow scientists, some of his fellow scientists who really opposed dropping nuclear weapons on Japan. At the very least, they said you could drop it on some uninhabited island. Oppenheimer said, “Well, if you do it, it’s going to terrify everyone. It will lead to some rational opening up of nuclear arms talks and reduction,” and quite the opposite happened. You say it’s his nightmare. What was his dream?

Matt Korda

That’s a great question. He was certainly someone who was a supporter of international control over nuclear weapons. In the movie, they talk about this a little bit, where he mentions that he wants to make the secrets of the atomic bomb more public, and there are these great letters. Our organization was founded by many of the same scientists who worked on the atomic bomb.

Paul Jay

Do you mean the Association of American Scientists?

Matt Korda

The Federation of American Scientists, yeah. We used to be the Federation of Atomic Scientists, and that’s how it was founded, and then it became the Federation of American Scientists. There were these great letters from Oppenheimer talking about nuclear transparency back in the mid to late ’40s, where he’s talking about how if we keep the secrets of nuclear power locked up just for the United States to understand, it’s only going to do a disservice and lead to an arms race. He has these great documents that are incredibly relevant today, especially when we think about how all countries, including the United States, are taking very serious steps back in terms of transparency.

We just published a piece a few days ago about how the Biden administration refused to declassify the number of nuclear weapons in the U.S. stockpile. That was something that the Obama administration used to do, the Trump administration stopped it, and the Biden administration is also no longer continuing with it.

Paul Jay

Now, this is the guy who ran as president saying he would declare no first strike and then changed it once he became president and has refused to say no first strike.

Matt Korda

Yeah, this is the situation that I think a lot of presidents get into. No matter what their personal feelings are about nuclear weapons, they get into office and, in many ways, get briefed to death about what’s feasible, what’s not feasible from, I guess, a military standpoint, what the allies will and won’t like. It becomes easier to do nothing as opposed to making a significant change towards policy. It is really unfortunate because we’re seeing that, in many ways, pretty much every nuclear-armed country, but it’s most disheartening in the United States, is taking very serious steps back when it comes to things like transparency and being publicly accountable with regards to their stockpiles.

Paul Jay

I don’t think people understand how the danger has increased as compared to decades ago. To some extent, what Oppenheimer hoped for, to some extent, limited extent, did happen. [Richard] Nixon and [Leonid] Brezhnev negotiated an anti-ballistic missile treaty in 1972. [Ronald] Reagan and [Mikhail] Gorbachev, and even before that with [John F.] Kennedy. There were real negotiations that at least showed some rationality to limit nuclear weapons. If I understand it correctly, we’re now living in a period where there are virtually no treaties that mean anything anymore and no negotiations.

Matt Korda

Yeah, that’s completely right. The last bilateral strategic nuclear treaty that limits the number of weapons that countries are allowed to deploy, that last treaty is called New Start. New Start is effectively dead. Russia, under a very poor legal basis, announced that they would be suspending the treaty. There isn’t a provision for a suspension in the treaty. As a result, the U.S. took reciprocal measures and also said that they’re not going to be providing data to Russia anymore. The treaty is effectively non-existent at the moment. It doesn’t really look like there’s much of an opportunity to resurrect that because Russia, from the U.S. standpoint, is still in violation of the treaty. There really is not much ground between the two countries anymore to really be particularly interested in arms control.

I think, more broadly speaking, something that’s quite frustrating is that we’re seeing that our arms control is very much falling victim to what I think is happening in a lot of cases, which is ultimate domestic politicization. Arms control used to be something that could be supported by both sides of the aisle here in the United States. It was something that was supported. It was understood to be something that you could negotiate an arms control treaty with an adversary that you hated because it was very important to do so, and it tangibly reduced nuclear risks.

Today what we’re seeing is that there’s this very emotional and knee-jerk reaction to the idea of even talking to Russia or even talking to China because these are the bad guys, quote-unquote, the bad guys. It’s very domestically quite difficult. Whenever you have politicians who say we should be engaging with Russia, engaging with China on things that would tangibly improve the state of the nuclear order, very quickly you hear calls for saying, well, now is not the right time for that because China is doing X, Y, and Russia has invaded Ukraine, which is true. That being said, you still have to engage with these countries because otherwise, you have a global arms race. It’s frustrating to see that.

Generally speaking, when you look in Congress right now, there are very few individual politicians who would really go out on a limb to support arms control anymore.

Paul Jay

I think it’s important because, in mainstream media, it almost never gets talked about. Probably the most destabilizing thing in terms of the demise of nuclear treaties and proper negotiations was the abrogation in 2002 of the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty. I don’t think most people understand that the treaty was negotiated, if I understand it correctly, in ’72, and it was a great achievement. The Vietnam War was raging. The Cold War was raging. Still, Nixon and Brezhnev make a rational deal. They know that if any side gets an effective anti-ballistic missile system, it destabilizes the parity that the other side is going to think a first strike is coming, and they’re going to launch the first strike.

What happened? It’s an interesting history, just quickly. In 1990, Charles Krauthammer, one of the fathers of neo-conservatives, called for abrogating the treaty. In the Project for New American Century, which was all these neo-cons that wound up being around [George W.] Bush, [Donald] Rumsfeld, and [Dick] Cheney, the Project for New American Century document called Rearming America’s Armed Forces, the number one proposal is abrogating the ABM treaty with this massive buildout of a global ABM force.

After 9/11, what’s one of the first things these guys do? Abrogate the ABM treaty. Why? Because it’s a damn money pit. How much does it cost to build an effective ABM system? It’s how long is a piece of string. Whatever you can bloody get Congress to come up with, that’s what it costs. It’s a money pit.

We’re now living in a period where the Americans are rebuilding a serious ABM system, I got to say, with the support of Canada. I mean, how dangerous is this piece of it? How dangerous was the abrogation of that treaty?

Matt Korda

It’s very, very difficult at this point to ignore the very real connection that exists between offensive systems and defensive systems. The defensive systems; it’s hard to even call them defensive systems because, as you mentioned and what many Cold War realists understood during the Cold War was that these defensive systems, in many ways, support an offensive posture. If you have a good enough defensive system, it allows you to engage in potentially a first strike, knowing that you can mop up what’s called the ragged second strike that comes back at you, and therefore you increase your invulnerability. These are very destabilizing systems when deployed at scale.

When the abrogation of the treaty happened in 2002, this was something that was done very much; as you mentioned, certainly, there’s a financial component to this, but also for very emotional reasons at the time— 9/11 had just happened. I think it was Rumsfeld at the time who said, “Deploying something is better than deploying nothing.” I think many folks would suggest now that that’s actually not true. Deploying nothing would have been much better than deploying something, especially since the system that was deployed was such a poor system. So much money was put into it, and the test record is so terrible.

You run into this situation where at the time, you had Russian diplomats and Chinese diplomats who engaged with the United States and said, “If you are serious about deploying these systems, we are going to take steps to deploy offensive systems to circumvent your defensive systems.” That’s classic action, reaction, arms race dynamic. The U.S., at the time, basically wasn’t particularly interested in engaging with those viewpoints by virtue of the administration that it had at the time and what those priorities were. We’re seeing now, 20 years later, what the result of that is.

In March 2018, Putin gave this speech, and it was very well covered in the media because, at the time, he introduced six new systems. What a lot of folks in the media called exotic strategic systems. It was these weird things. One was this underwater nuclear torpedo. One was a nuclear-powered cruise missile that could circumnavigate the globe. One was this laser.

Paul Jay

Hypersonic.

Matt Korda

A hypersonic glide vehicle. Five out of those six systems were specifically designed to circumvent missile defenses, and Putin said so during his speech like 20 times. He mentioned the ABM treaty, and he said, “The U.S. didn’t listen to us then, so listen now.” You can see these threads that go between 2002, the decision that was made and what we’re seeing today.

Certainly, I don’t defend Putin here, but you can see that countries react to things all the time. The deployment of those kinds of systems, I’m sure there are lots of other drivers for those because, just as in the United States, there are financial drivers for these things. There are prestige drivers. Hypersonics are a big deal, and all these things. It’s impossible to ignore that there is at least some driver that relates to missile defense in some way because that is the public justification that he uses for deploying those systems.

It’s the exact same with China. China, we are also seeing, is deploying ICBMs at scale. They’re very likely putting multiple warheads on those ICBMs. These are things that you do.

Paul Jay

Up until recently, they had not been doing that. They had kept their forces, nuclear forces, relatively modest.

Matt Korda

Yes.

Paul Jay

Now they’re going to catch up.

Matt Korda

Just like with Russia, there are a lot of reasons why China might choose to do these kinds of things. I don’t think all of them are a reaction to the United States. But certainly, I think it’s very hard to ignore that they’re looking around the world, seeing what other countries are doing with regards to their defensive systems, and saying, “Okay, we need to build around that,” because that’s the nature of the arms race.

Paul Jay

If you’re sitting in the American military-industrial complex, which is exactly where the guys that wanted to abrogate the treaty in 2002 were, I mean, Cheney was Haliburton. Everybody knows all the deep contacts of Rumsfeld and the people around Rumsfeld, Cheney, and the military-industrial complex. They must have been grinning ear to ear when they abrogated the treaty. I would guess the same thing is true in the Russian military-industrial complex and the Chinese military-industrial complex.

Matt Korda

Yeah.

Paul Jay

But the Americans go first. The Americans are the ones that are the far bigger threat of a first strike than the other way. There’s no evidence there’s ever been a day where the Soviet Union or Russia ever planned a first strike against the United States. We know there actually were plans by the United States to have a first strike. A lot of that came out of Ellsberg’s work, but other work as well. How can they not respond? How can money-making not be one of the main driving forces on the American side? Because if it made sense to have an ABM treaty in ’72, why all of a sudden didn’t it make sense in 2002?

Matt Korda

Yeah, it’s a good question because, in 2002, the stated response or the stated justification was to be able to respond to what they called rogue states, specifically Iran and North Korea. The concept of an Iranian nuclear-armed ICBM, I think, is nowhere on the horizon anytime soon.

Paul Jay

The American national security estimate in maybe 2003 or 2002, but right around that period, maybe 2004, was that there was no Iranian nuclear bomb program, certainly no evidence of one, and certainly not enough evidence of one to abrogate the treaty, which was clearly done on a scale that had nothing to do with Iran anyway.

Matt Korda

I think the problem that we often see is that it often feels like multiple sides are talking past each other. With regards to the U.S., what they often say when they try and talk about their defensive systems is they say these systems are not postured towards Russia and China because they can’t. They can’t be. Technically speaking, they are not capable of shooting down the types of missiles that Russia and China have, which is true.

But that being said, Russia and China don’t accept that justification because they look at what a future U.S. missile defense architecture could look like, and they say, you know what, right now, maybe in this particular year, this isn’t going to be effective against our deterrent. But maybe in 10, 20, 30 years, if the U.S. keeps building and the messages that they hear; for example, when President Trump unveiled his missile defense review, he said, “This is designed to shoot down any missile from any target from any country.” It was very clear that these lines that used to exist where it was like before it was much cleaner when they said, “This is specifically for third countries. It’s not for Russia and China.” Now everything is blurring together. It makes it a lot harder for the U.S. to go out and say, “No, we’re not trying to undermine your deterrent Russia. We’re not trying to undermine your deterrent China,” because these countries are getting these messages that basically say, “Yeah, we are trying to undermine everyone’s deterrent by deploying missile defenses at this large of a scale.”

Paul Jay

For people who don’t get the ABM logic and tell me if I’m correct, the threat of if the United States had a relatively effective ABM system, it’s not that it defends the United States. That’s not a threat to Russia or China. The threat is that the United States could launch a first strike and then so degrade either the Russian or the Chinese capability of a retaliatory second strike that the ABM system then would be able to deal with a significant amount of that so that the second strike, retaliatory strike, wouldn’t have as much effect. In other words, it would embolden the U.S. to have a first strike. In some ways, I think the American military even talks about wanting that. They want an overpowering nuclear presence to intimidate the other side. What it really does, if I understand it correctly, is it makes the other side say, “Shit. If we see anything coming, we better preemptively strike.”

Matt Korda

Yeah, it’s interesting. In this sense, I guess it’s important to note that the U.S. is certainly not the only country that is deploying missile defenses at scale. That is the logic of how a defensive system can support a first-strike posture. We’re seeing Russia also make pretty tremendous strides with their missile defenses. China is also doing the same thing. I want to note that this is something that is happening all across the board.

Paul Jay

But triggered because the Americans abrogated the treaty.

Matt Korda

Perhaps, yeah. I guess it’s interesting to think about what the drivers are specifically for each individual country. There are so many reasons why countries choose to build up their forces. A lot of it is mirroring, too. It is a great question. What would happen if the U.S. did not abrogate the treaty in 2002? Does all of this happen anyways, or do we have a much more stable world? I tend to think the latter, but there also are a lot of other drivers for why these things happen.

Paul Jay

There’s a recent speech by Jake Sullivan— he’s the national security advisor—where he says, “In the past, Russia and the United States were able to negotiate nuclear arms limitation treaties even at times of great stress and so on, even when the world was very dangerous. He said something which I thought was good because that hasn’t really been the language coming out of Washington since the Russian invasion of Ukraine. He said, “In spite of that, there still could be negotiations.” That was, at least in language, a good statement.

Let’s take him at his word for the sake of argument anyway. I don’t know if it’s just rhetoric at this moment, but if it is, it’s better rhetoric than previous rhetoric. What do you think should be the agenda for such talks? Obviously, it has to be U.S., Russia, and China, at least, if not all of the nuclear-armed countries, but certainly the three major ones. What should they try to do? Is it a new ABM treaty? What is it?

Matt Korda

Yeah, so that’s a great question. Certainly, it’s difficult between Russia and China because there are such different histories there and such a different level of experience when it comes to arms control. The U.S. has more than 50 years of dealing with Russia on matters of nuclear weapons. As a result, there is a shared language. There’s a shared understanding of how deterrence works. There’s a shared understanding of which things are important to put into treaties. I think the U.S. has a good understanding of what Russia’s priorities are, and Russia has a good understanding of what the U.S. priorities are. It’s just a matter of trying to make those fit.

With China, it’s much harder because there is zero history of negotiating with them at all on matters of nuclear arms. It’s really complicated, right? The Trump administration, I think their instinct was good when they said, “We want to do a negotiation with the U.S., Russia, and China.” I think the way they went about it was, to be frank, pretty sloppy and was probably done not in the best of faith because it was done in the context of trying to expand New Start, which was something that was never going to happen. The idea of bringing China into negotiations is a good impulse. The problem with that is that you have to start from square one, very much so. Even just thinking about what concepts mean, what deterrence means. These things mean very different things in U.S. strategic culture than they do in Chinese strategic culture. That makes a really big difference.

When the U.S. goes and says, “Hey, we want to do an arms control treaty with China,” I’ve seen some interpretations in which China, even the term arms control, can have a very different connotation. It can mean much more, I guess, an idea of the U.S. controlling China’s arms rather than a mutually constructive deal. Even the language that we use has to be decided and agreed upon way in advance. We are, I think, a decade at least away from a treaty with China. Even happening at a non-formal level, like a track two with just civil society or just academics to understand what it is that China wants. Are they willing to be transparent about their nuclear forces? China is very opaque about what it plans to do with its nuclear arsenal. If you want to do a treaty–

Paul Jay

Well, the thing is, with China, they’ve got experience, including 1958, where the United States said to China, “If you use conventional forces against Taiwan, we’ll use a nuclear bomb against you.” [Dwight D.] Eisenhower actually okayed it. There are minutes of a meeting of the Joint Chiefs of Staff discussing using a nuclear bomb against China in 1958. The only reason it didn’t happen is because I guess Mao [Zedong] knew of the threat and pulled back and stopped shelling those islands. I always screw up the names of these islands right near the Chinese Coast— the Taiwanese islands.

The threat of an American first strike in defence of Taiwan has been a real thing in history. Even then, for decades and decades, the Chinese didn’t do this buildout to try to get the nuclear weapon parity that they’re doing now. Surely they have people that study the history of these kinds of treaties. What they’ve said, like they’ve said this on climate, and I’m guessing they might say the same thing on nuclear arms treaties: how do we expect cooperation with you? They’ve said it on climate like I said, but if I were them, I’d say it on nukes.

One, we don’t know who’s going to be president in two years. If it’s someone who wants war with China over Taiwan, and certainly, the rhetoric coming out of the Trumpest forces is even more aggressive than the Biden rhetoric. Although I think the Chinese understand that Biden’s rhetoric is to do more with domestic politics. Don’t look weak on China. Like all the big corporate leaders that recently went to China, Larry Fink from BlackRock and Apple was there, and [Bill] Gates from Microsoft was there, and now they sent [Antony] Blinkin and [Janet] Yellen.

I think the Chinese understand that the Democrats, more or less, are going to leave the status quo with Taiwan, but they don’t know what to expect from the Trump administration. It’s the Republicans in the House that established this committee to go after anything to do with China.

Part of the problem, as you alluded to earlier, is that the Republicans take this big step, and then the next Democratic administration doesn’t undo it. So even though Bush abrogated the treaty in 2002, nothing stopped Obama from re-installing the ABM treaty, as Biden did with the Paris Accord. The Republicans take a big Cold War-ish step, and then the Dems leave it.

Matt Korda

Yeah. This is a big problem. Certainly, when it comes to China, these types of academic exchanges that used to happen all the time between American academics and Chinese academics, and these are real opportunities to be able to engage with China and understand at least what it is that is the dominant line of thinking when it comes to nuclear weapons. A lot of those things have been restricted now. You can’t do many of those types of academic exchanges anymore. That restricts our ability to understand and prepare for a potential new treaty. It can be quite frustrating.

Paul Jay

Well, the Chinese had said on the climate thing when [John] Kerry went, “It’s great you’re here, and yes, we should be talking about climate, but how do we take you seriously when you’re still restricting and waging chip wars against us? You’re even sanctioning technology to create better batteries for solar power, which essentially would help in dealing with the climate crisis.” I think the onus really is on the U.S. to take more seriously the risk of nuclear war and climate crisis and have to make some steps to make it look like negotiations are for real. As I said, Sullivan’s words about the negotiations are good, but it’s not enough if you don’t take some concrete steps, certainly on the Chinese side, to drop some of these sanctions.

Matt Korda

It’s really difficult. The point you made about not knowing who is going to be the president in a couple of years and having a potential tremendous reversal in policy or, I guess, accelerating what would otherwise be a destabilizing policy; that’s really serious. It comes into play with Iran. It comes to play with Russia. I think what we’ve seen is that many countries don’t view the United States as a particularly stable negotiating partner anymore. This is a huge problem. The U.S. needs to be a leader in arms control and disarmament. It’s really difficult to do that when you could have all that progress undone in a matter of four years.

Paul Jay

In terms of Russia, people that watch theAnalysis know I’ve denounced the Russian invasion of Ukraine hundreds of times. That said, I’ve also said, and many of my guests have said, there needs to be a negotiated settlement, and you can’t underestimate the danger of nuclear war. The U.S. position seems to ignore that risk. I don’t know how serious the risk is of a deliberate use of a tactical nuclear weapon by the Russians. There are some serious people in the foreign policy circles in Russia that have talked about using a tactical nuclear weapon against Poland as a shot across the bow of NATO. I don’t know how seriously one should take that.

The danger of miscalculation is that Russian, not Russian, the missile that did land in Poland and turned out to be Ukrainian; what happens when one of those goes astray and lands somewhere near Moscow in such a situation? I don’t get that there’s a serious consideration of the risk of accidental nuclear war as a result of Ukraine.

Matt Korda

Yeah, I certainly think this is the case in a number of hotspots across the globe, too; you mentioned the case in Ukraine. We saw, I think it was just last year, India accidentally launched a missile into Pakistani territory. This is the first time in decades that a nuclear-armed country accidentally launched a missile into another nuclear-armed country’s territory. There are a lot of very serious incidents like these. You mentioned the one in Ukraine, in Poland, the one in India. But these kinds of incidents happen more often than people think. The danger here is that I think many folks who work in this field and think about deterrence a lot consider that perhaps escalation can be controlled a little bit better than it can be in real life.

We have no idea what happens when a weapon goes off. We don’t have a realistic way of estimating what will happen. In terms of how the conflict will change, we can wargame things all the time and imagine what might happen if a weapon accidentally goes off in a particular context, but we have no idea. It’s going to be a very degraded information environment, and decision-making is going to be really confusing. People will be trying to attribute what happened, and there’s going to be misinformation and conspiracy theories and all these things. It’s going to be an incredibly muddy situation. I think presuming that we are able to control the after-effects of a nuclear detonation is dangerous. It leads to very risky and, I think, perhaps, overconfident thinking.

I certainly think you’re right. I think that probably in every country, not just the United States, I would imagine this is certainly the case in Russia and China, India, Pakistan, North Korea, that there is this presumption that we can control escalation and we can control how a nuclear war is going to play out. I certainly wouldn’t want to gamble on that. I don’t think that that’s particularly realistic.

Paul Jay

It’s nuts.

Matt Korda

Yes.

Paul Jay

Ellsberg called it institutional madness. It’s institutional madness fueled by money-making.

Just finally, you’re in D.C. I’m not sure how much you, but a lot of people working on these issues interact with congressional staff and members of Congress. It’s like this topic is practically taboo. I mean, nobody talks about it.

Matt Korda

The number of people in Congress who I would say really pay very close attention to nuclear issues is very small. Perhaps a dozen really dedicated folks who really think about these things a lot. This is not nearly enough. Certainly, during the Cold War, even immediately after the Cold War, Congress took its role in foreign policy, but really in nuclear policy very seriously. You would have these teams of Congress people who would travel to Russia to supervise and advise on negotiations. They participated in New Start negotiations in 2010. This is something that you don’t see anymore. I can’t imagine another real serious congressional engagement on arms control because, I guess, for many reasons, Congress, in general, I think is very much not particularly interested in exercising foreign policy power anymore.

Paul Jay

There was some initiative by Ed Markey and a couple of others, but it didn’t seem to go very far.

Matt Korda

I mentioned there are a few Congress people who are really interested, and Ed Markey is certainly one of them. They have a really dedicated nuclear team there, and they’re focused on issues like no first use and trying to reduce the number of weapons in the U.S. arsenal, promote arms control, and things like that. These are really productive steps, but they are very much operating with very few allies in Congress. It’s difficult. This is the job of many folks in DC to try and go to the Hill and educate and explain a little bit more about why these issues are so important, why we should be engaging in arms control, reaching across the aisle to try and make arms control a little bit more, I guess, less politicized and a little more domestically palatable again.

It’s really difficult because, just like every other issue now, it has a bad taste to it, especially following the invasion of Ukraine. No one wants to be seen engaging with Russia anymore, which I can understand, at least very much on an emotional level, because of what’s going on in Ukraine. At the same time, these are exactly the moments when it’s really important to be engaging in arms control because, unfortunately, by the way and how the world works, you have to deal with all of these other very intense and serious nuclear powers because the alternative is so much worse.

Paul Jay

All right, thanks very much for joining us, Matt.

Matt Korda

Yeah, my pleasure. Thanks so much.

Paul Jay

Thank you for joining us on theAnalysis.news. Please don’t forget there’s a donate button at the top of the website. If you’re on YouTube, hit subscribe. If you’re on all the podcast platforms, come on over to the website, check it out, and hit the donate button. Thanks for joining us.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | TuneIn | Deezer | RSS

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter

Matt Korda is a Senior Research Fellow for the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists, where he co-authors the Nuclear Notebook––an authoritative open-source estimate of global nuclear forces and trends. Matt is also an Associate Researcher with the Weapons of Mass Destruction Programme at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) and co-authors the nuclear weapons chapters for the annual SIPRI Yearbook.