As the U.S. and Russia discuss a possible ceasefire, what role do the Ukrainian people—especially the working class—have in shaping the outcome? Paul Jay speaks with Ukrainian political scientist Denys Gorbach about the war, class dynamics, and the neoliberal assault on workers’ rights during the conflict—a rare, progressive, class-conscious look at the war in Ukraine.

Paul Jay

Hi, I’m Paul Jay, and welcome to theAnalysis.news. In just a few seconds, we’ll be discussing the current negotiations going on to either get a ceasefire or perhaps some “peace.” I’d put quotation marks around that because we’ll see in whose interest the peace is. We’ll be back in just a few seconds with Denys Gorbach.

As the negotiations are getting going, mostly between the United States and Russia, it seems very generous of them to include Ukraine in these discussions because it seems like it’s almost an afterthought what Ukraine wants. But it’s even more an afterthought– I shouldn’t say an afterthought; it’s a non-thought. What do the Ukrainian working class and people want out of these settlements? When Western media and I suppose most media in the world, discusses the situation in Ukraine, you wouldn’t know it’s a class society. Of course, you wouldn’t know it’s a class society in the United States or Canada either because it’s almost never talked about.

Today, we’re going to talk about Ukraine. We’re going to talk to someone who’s been studying the Ukrainian working class, who is Ukrainian, now living in Sweden, but has a take on this, which we often don’t hear a progressive left take on what the Ukrainian people really want and need at this moment.

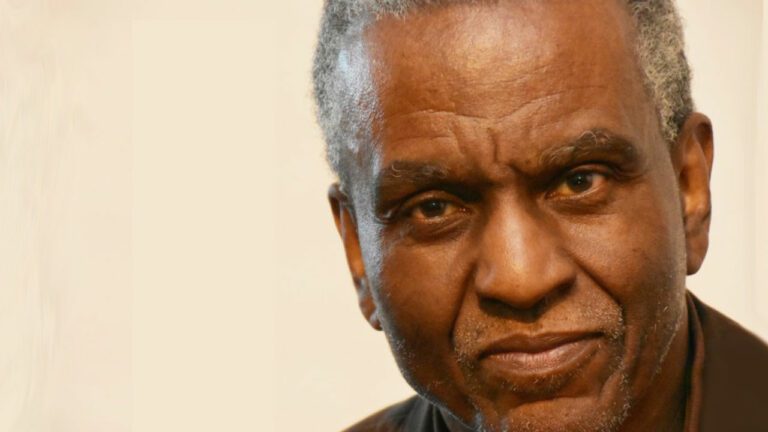

Now joining us is Denys Gorbach. He’s a Ukrainian political scientist. He studies the working class and national populism in Ukraine. He earned his Ph.D. in 2022 and is currently a postdoctoral researcher at Lund University in Sweden. Thanks for joining us, Denys.

Denys Gorbach

Thank you. Thanks for having me.

Paul Jay

Let me just say that I interviewed Denys in 2022, and we did a three-part [interview], I believe, where we talked about some of the current modern history, what happened in 2014, and we discussed a lot of the backstory to where we are now. Of course, a lot has happened since then. We’re going to start with the current moment and then dig a little more into the history and also, you could say, the balance of forces within Ukrainian society.

Denys, start with this: to the extent the Ukrainian working class can express itself as a class, which I expect is not all that much, and honestly, it’s not all that much in a lot of countries, never mind a country that’s been invaded. Let me just start by saying that I know some progressives in North America don’t come out and say this very explicitly, but let me say it explicitly. The Russian invasion, in my opinion, was a total violation of international law, the UN Charter, and the conclusions of the Nuremberg trials that found wars of aggression the highest crime. I think that’s what we are dealing with, with the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Not to say, the expansion of NATO wasn’t a provocation, but it doesn’t matter. Provocation or no provocation, defending a sphere of influence is not justifiable under international law. I’m trying to make that utterly clear from the beginning. I’m guessing you agree with me, Denys, if you don’t say so. Otherwise, let’s talk about what the Ukrainian people, the working class, want and need out of these negotiations.

Denys Gorbach

Yes, thank you, Paul. That was probably a useful caveat in the beginning. Yes, it is indeed true that the working class is not prominent in all these discussions, which are mostly about geopolitics, international relations, and so on. If we put the simple question, what do the workers want, the answer would be just a simple, yes, they want peace. If we try to unpack what peace does one want, in every occasion, that might be a bit more complicated.

So yes, in the very simplest terms, peace is indeed the term and the word that everybody has on their mouth in these times. Everybody is extremely tired of the war, morally, if not physically; I mean, those people who are still alive and are not injured. There are not so many. Peace, in its simplest meaning, is the cessation of hostility.

Now, and this is true to the extent that when Trump won the elections but had not yet become President of the U.S., according to what people have been telling me and what I have been able to observe from afar, there was a renewed hope that finally it will somehow end. There is this saying in Russian and Ukrainian that a horrible end is better than a never-ending horror. But then, when Trump did actually assume the presidential title and unfolded his vision of how peace should be concluded, that gave a second thought to many people. As much as everybody wants people to stop getting killed on the front lines and people to stop getting killed by missiles in their hometowns, as much as that is true, the caveat about the stability of that peace is not only something that you can hear among journalists or elite actors. This is something that is understood by so-called ordinary citizens, ordinary Ukrainians, and working-class people.

I can speak about the city that I happen to be a native of and also happens to be the native city of Zelenskyy, by coincidence, which is called Kryvyi Rih, in the southeast of Ukraine. The city has not been touched directly by the war. The front line is 100 kilometers away from it. During the first two years of this ongoing war, the city has been relatively spared. The bombing that did take place during the first half of the war was more destructive in Kyiv, for example, in the capital, than in Kryvyi Rih. During the last roughly year or so, there has been a systematic, much more destructive bombing campaign of hotels and other civil infrastructure.

People, first of all, naturally don’t like this situation. They’re not big fans of this way of living. They are anxious about the front line and land hostilities creeping closer and closer to the place where they live. The big fear is that today we sign a peace on whatever conditions. For that peace, frankly speaking, most people, in my opinion, would be completely, well, not completely, but would be fine with losing, in reality, the territories that have already been occupied. This sacrifice that they are ready to make is… I mean, they want to get something in return, namely the guarantee that this war will not be reignited anytime soon. This is the big question. Yes, people want the war to end, a peace or ceasefire, you name it whatever you want, because that’s not the main preoccupation of the diplomatic framing. The peace would be stable, and that’s a big question.

Paul Jay

Do we have any sense of what the people who are living in the occupied territories want? Obviously, the Russian propaganda is such that the people who speak Russian want to be part of Russia. It wasn’t really the history of Donbas and those areas. They originally wanted autonomy within Ukraine. They didn’t want to be subject to a right-wing rule from Kyiv. At least before, if I understand it correctly, it wasn’t that they wanted to be part of Russia. Do we actually know what people want? The thing I find a little peculiar from the Ukrainian side, unless I’m missing it, there’s no demands for a UN-supervised referendum, something where we actually find out what do people want, because it seems to me it should be more than a consideration.

Denys Gorbach

Yes, from the point of view of the Ukrainian government, there’s no need for a referendum. They argue from their legal position, from the point of view of international law, they have this sovereignty, and they don’t want this sovereignty to be challenged. From the point of view of radical democracy, whatever you might call it, sure, it’s not a crime for me to imagine a referendum, which would not be a mock referendum that Russia did hold in various territories that it occupied, but under completely transparent conditions with possibilities for all refugees to participate. For me, it’s fine. It’s true that maybe you cannot hear it from the Ukrainian side because this would undermine the Ukrainian side’s legitimacy from the outset. But yes, as a leftist activist from Ukraine, I personally don’t have a problem with that.

Paul Jay

If they’re going to accept a peace agreement that essentially allows the annexation of Donbas by Russia, they’re giving up on the sovereignty argument anyway, or they’re not. But if they’re not, it sounds like there isn’t going to be an agreement.

Denys Gorbach

That’s where diplomatic framing comes in, because if we’re speaking about peace in its full legal term, that’s indeed impossible. I would bet any money, almost any money, on the impossibility of peace, strictly speaking, precisely because of that. Politically, that would be unthinkable for the Ukrainian government to sign a peace [treaty] that would acknowledge Russian sovereignty over Crimea, much less over the territory it’s conquered lately.

What they are discussing now, I’m pretty sure, with Trump is something more akin to the Korean scenario, where the war has never concluded. We have a 70-year or however many year-long ceasefire without the necessity, hence, for South Korea to recognize officially the existence of North Korea and vice versa. So that is the realistic formula of, well, not peace, but a ceasefire, a cessation of hostilities. That’s why I was talking about that. That, yes, would allow Ukraine to preserve its face.

That’s the same thing with the Cyprus situation if you are familiar with that. Again, the Republic of Cyprus has not acknowledged the Northern Republic since 1974, since its inception. That does not, in fact, have big repercussions for everyday life. I was there. I visited this island a few times. You can cross the border almost as well as you might cross any other border. Officially, there is still this subtle difference. Kosovo was the same thing. This is what we’re talking about now in terms of possibilities legally.

Paul Jay

Yeah, but it winds up de facto being a Russian annexation of Donbas. And whether the Ukrainian government recognizes it or not, they’re going to be having Russian identity papers, Russian passports. The schools will be Russian. In all likelihood, there won’t be much of a Ukrainian language left. So as you say, the Ukrainian government gets to sort of save face.

This is why I started this interview by asking what does the Ukrainian working class want? Right from the very beginning, I don’t know if you remember our last interview, but I always actually, and it’s hard for someone sitting in a comfy Toronto to say anything about a people that have been invaded and are being slaughtered. And I have to say, I’ve always been almost as concerned about the slaughter of Russian workers as I have been about Ukrainian workers. There’s no reason why Ukrainian and Russians should be killing each other like this. But we have to separate the Ukrainian oligarchy and Russian oligarchy and look at these things from a class point of view.

I actually never understood why some of the Ukrainian left supported a conventional war in defense of Ukraine, meaning this, First of all, it was justified. In every respect, the Ukrainians have a right to fight any way the Ukrainians decide to fight. It doesn’t mean a conventional war was the right way to go.

In Canada, I believe, and in fact, even under Canadian law, Quebec has the right to self-determination. There have been referendums, and the independence movement narrowly lost. But, as an English-speaking Canadian, while I recognize the right of Quebec to separate, I really wish and hoped that they didn’t, and I still do because I think Canada would be a far more right-wing country without a Quebec in it. I think it’s better for the working class of Quebec and all of Canada that Quebec is part of Canada. That doesn’t mean they don’t have a right to leave, but I don’t think it’s the best choice. I felt somewhat similar about the invasion.

Why fight a conventional war against the Russians when there could have been mass protests right from the beginning? There could have been general strikes and ways not to empower the Ukrainian oligarchy and be dependent on the Americans. Now, maybe I’m dreaming in technicolor because certainly it never happened. Even now, at this moment, there needs to be a discussion about what’s good for the Ukrainian working class and people, and not just hand whatever’s left back to the oligarchs again.

Denys Gorbach

Well, that’s several questions that you have here. Conventional war, I don’t know; to me, frankly, I don’t find a lot of other options. Given the situation in which you find yourself on the morning of the 24 of February, 2022, what else do you have as a choice? There is already a war. That is to say, you are already being invaded. You can either ignore it, so keep being invaded, or you can try to prevent it by whatever means possible. That is, yes, participate. Take your turn and participate in the conventional war. So a general strike, yeah, as an idea, politically, I come personally from anarcho-syndicalist tradition, so I’m all for eternal strike as such. But it is a weapon, like you said, against the Ukrainian oligarchy, Ukrainian bourgeoisie, and the Ukrainian ruling class, not against the foreign army that progresses through your territory. The real dilemma, as I can reconstruct it, is, are you going to fight or are you going to sit at home and see what happens next?

Paul Jay

Let’s just be clear. Listen, what I’m suggesting clearly wasn’t possible because that wasn’t where the balance of forces was. But I’m not suggesting staying at home. I’m suggesting imagine when the tanks are coming up the highway to Kyiv right from the beginning, hundreds of thousands of people sit down in front of those tanks, millions of people protest against the Russian invasion because the Russians were trying to claim there is no Ukraine. They’re trying to claim that people wanted Russia to come in. But anyway, that’s maybe a little abstract at this point now because it didn’t happen, and I guess it didn’t happen for reasons. Go ahead.

Denys Gorbach

I mean, in fact, that didn’t happen in the very first hours and days. But in the first weeks that took place, so there was a natural experiment of that sort in cities occupied by the Russian army. Namely, there were several such instances, but the clearest that I can remember is Kherson, so the regional center, the regional capital that the Russians took very quickly. For a while, for several weeks, maybe a month, the first month of the occupation, the Russian army, unlike those places around Kyiv, in Kherson, they were more or less cautious, at least publicly. They tolerated public protests against the occupying army, and public protests there were. People did come marching, and marched along the central streets of the city, swearing at the soldiers that stood nearby. There was something going on along the lines that you have just suggested. But then, as soon as the general situation in the war allowed the army, the occupying army, to behave more freely, they proceeded with their typical arsenal, that is, riot police, and then all kinds of unpleasant places like torture chambers were activated.

Another geographical point in Ukraine in that period of the beginning of the invasion was Kharkiv, the northeast of Ukraine, which was not finally taken. But it was very telling how one of the groups of armored vehicles that were hit by a Ukrainian artillery missile. It turned out that the vehicle contained ride police and the tools that they use, especially the anti-crowd dispersion stuff, all this. So not military, not equipment for the warfare, but the equipment for dispersing crowds violently within the city they already control, which means that I would not really bet on the possibility of such peaceful protests.

Paul Jay

I’m not saying it has to be peaceful. I was about to make this point. I’m not in any way suggesting it shouldn’t have been armed. I guess what I’m getting at and trying to bring it back to today… and I’m saying this and acknowledging that it wasn’t possible because of the balance of forces, but the question of which class is going to lead the resistance.

The oligarchs of Ukraine, in my opinion, I don’t know if you agree, they did to some extent contribute to facilitating at least the excuse for this invasion, if not, to some extent, allowing Russia to justify it to the Russian people in the sense that the Ukrainian government could have taken the NATO issue right off the table. I know there were Ukrainian voices prior, and then in the lead-up to the invasion, academics, intellectuals, and others saying, “Just declare neutrality. No NATO for Ukraine.” Instead, the oligarchs didn’t do that. The government didn’t do that. And they put all their eggs in the American basket. It wound up that the whole war became dependent on the U.S. And then, of course, we know what’s happening now. You get a shift in what the Americans want, and then the Ukrainians are going to almost be watching this from the outside. They’re going to wind up with a settlement, by the sounds of it, that could have been had three years ago.

Denys Gorbach

Frankly speaking, I would not even bet on this settlement being achieved even now with Trump, very soon. Because for now, it seems that, to me, neither party, meaning Ukraine or Russia, is actually willing or ready to stop fighting. Well, Russia is advancing, so there is no reason why Putin would want to stop advancing. The Ukrainian elite also still believe they can somehow change the situation in their favor on the battlefield. They are not really that desperate to conclude this. Yes, it’s true that with the time that passes, Ukraine’s negotiating position probably risks things getting worse and worse. That’s true.

Paul Jay

I think Trump seems absolutely, overtly committed to this world. A world of big powers having a sphere of influence. Russia’s sphere of influence is based on how they assert it, more or less. Eastern Ukraine is going to be theirs, and Western Ukraine is going to be “ours.” Trump is going to find a way to plunder the resources of Western Ukraine overtly. They’ve got this mineral deal they want, and that’s just the beginning because clearly, they’re going to try to bleed out of Western Ukraine everything they can because America first and Ukraine and everybody else way later.

Denys Gorbach

Yeah, this thing about the minerals is especially outrageous because the initiative, in fact, came from Ukraine. This was a very clumsy attempt on the part of Zelenskyy’s team to somehow ignite the interest of Trump for Ukraine.

In December last year, they saw that there was going to be this power shift in Washington, D.C. What are we going to do about that? We know that Trump is a businessman. He doesn’t care about big ideas. He cares about money and similar things. So let’s interest him in something material. So, yeah, oh, rare earth minerals sound exciting or sounds exotic. Then they didn’t expect this idea to reach Trump, and he jumped on it, and then he started actually demanding excruciating conditions. Currently, the same history is being repeated with nuclear power stations.

Again, as far as I am aware, the initial idea came from the Ukrainian side, and this was a way to convince the United States. Let’s have them on our side, at least for this big Zaporizhzhia power plant that’s currently controlled by the Russians. Let’s have the U.S. help us liberate at least that by having them interested materially in it. And then, well, better for Americans to take some profit from that power plant than the Russians completely controlling it.

Yes, now it’s growing out of proportion. Trump already said that he has to control all the generated capacity, nuclear capacities of Ukraine. Yes, it’s bad diplomacy. I don’t necessarily agree with you about NATO in the beginning, but that’s, again, in any case-

Paul Jay

Let me just say, whether one thought NATO might protect Ukraine or not, it’s almost irrelevant because Ukraine wasn’t getting into NATO. It wasn’t going to happen. It was all nonsense. Germany and France had made it clear. They kept using this word as an aspiration, some phony way to acknowledge it because they didn’t want to give up NATO’s right and supposedly Ukraine’s right to be in NATO, so they wouldn’t technically acknowledge that. But the truth of it is they all knew Ukraine wasn’t getting into NATO anytime soon. It was a ridiculous thing to put your stake in the ground about. It all started with the Bush administration saying this. The Germans and the Turks, they can’t believe it would ever have actually happened.

It’s not just symbolic. It’s about you’re offending the Russians’ right to a sphere of influence. So if you believe in spheres of influence, which progressive people shouldn’t buy into, but if you do, then you can say, “NATO is a threat to the Russian sphere of influence.” Okay, take the damn thing off the table because it ain’t happening anyway. But no, that wouldn’t have pleased the Americans. This is where I come back to, is that the Ukrainian oligarchy and government put all their eggs in this American basket, please the Americans, and of course, you wind up in a situation where now they can do whatever the hell they want to, including selling you out on the peace agreement.

I must say, it’s not like I’m arguing against the peace agreement. I’m very much for getting the damn thing, getting a ceasefire any bloody way possible, and then continuing the struggle in other ways.

Denys Gorbach

Yeah, the eggs, anyway, already had been in the same basket even before, so I would say-

Paul Jay

Then I come back to what shape is the Ukrainian working class in? What does it take to have a more independent, its own interests? Obviously, the big contradiction right now is between the Ukrainian people and the Russian invasion. But the contradiction between Ukrainian workers and the Ukrainian oligarchy is still very much in operation here.

Denys Gorbach

Yeah, of course. First things first, just to be clear, because still today, I read once in a while that the war is being waged exclusively by the ruling class, and defending Ukraine does not correspond to the interests of the Ukrainian working class. I don’t understand how the Ukrainian working class might not be interested in defending its livelihood.

That being said, of course, I will be the last person to affirm that Ukraine is a homogenous society. So sure, especially starting from ’22, in fact, the neoliberal offensive, it might be counterintuitive to many people, to me as well, it was a bit unexpected that during this war, the government has proceeded with the most intensive attack of neoliberal reforms against labor law, against the protection of labor, so the industrial relations, basically.

Paul Jay

Hold on, let’s get clear on that. You’re saying in spite of the need, you would think for national unity and maybe a time where they would be less aggressive against working class rights, they’re actually more aggressive. They use it as an opportunity to assert even more power over Ukrainian workers.

Denys Gorbach

Yes. If we try to explain it, we might, in fact, refer to your co-patriot Naomi Klein with her shock doctrine because it seems like the case.

In the spring and summer of ’22, when the Russian attack is everywhere, the Ukrainian Parliament, pressed by the government, passes one after another, three or four laws, consistently deregulating industrial relations, allowing zero-hour contracts and so on, explaining that this is allegedly all in the interests of European integration, which it is not, because zero-hour contracts are explicitly outlawed in the EU. In the European continent, they only exist in Belarus and in the United Kingdom.

Yes, there is this offensive that is not encountering any resistance because it’s difficult to mount resistance given the circumstances. Martial law outlaws public protests. Well, in reality, public protests do happen. They are tolerated. But precisely, if the government decides not to tolerate them, if they are contested, if it is an anti-governmental protest, then they might actually implement martial law and disperse it.

This means that if it was peacetime, for example, the Federation of Trade Unions of Ukraine it’s the largest one that exists in the country. It’s not super militant, not militant at all. It’s the legacy union structure from the Soviet Union. But to such a legislative attack, they would be able to respond by impressive mass mobilization. That’s what happened in 2011 when they were raising the pension age. So that’s why I’m talking about that possibility.

But yes, now the most that they can do and that they did was issuing a number of outraged appeals saying that, “Yeah, you guys in the government are not really nice. You’re not being nice to us. We should be all in this together.” So besides that, the only thing that they can do is appeal to the international community, which is good, but it’s not really working. It’s not super efficient.

Paul Jay

Let me ask you: you said early on in the interview that you thought most ordinary Ukrainians are ready for this to be over, ready for a settlement that maybe doesn’t recognize Russian annexation but de facto will live with it, to have it over with. But you also said that the Ukrainian government is not convinced that it has to be over, they still think they have a chance of gaining more territory back. I don’t know. But is what really is going on here that the Ukrainian oligarchs in government are afraid of what comes next within Ukrainian society if there isn’t a war? Meaning, is there going to be some accountability for all this? Is the working class going to perhaps wake up and say, “Okay, now who the hell got us into this mess? Why did we lose hundreds and hundreds of thousands of people for what?” Is one of the reasons the Ukrainian government may not be in to settle this because they’re afraid of their own necks and what comes next? Or am I dreaming?

Denys Gorbach

It is true that on the level, at least of representations of the discourse of popular imaginary, this is indeed a very recurrent motive that our guys should now come back from the frontline and turn their guns and their skills, their military skills, newly acquired against those in the high-placed cabinets in Kyiv. So that is almost commonplace. I mean, it’s a very typical element of popular discourse. Whether this is a real possibility, that I’m not sure. Because yes, Ukrainian workers do like to be very braggish about how they are going to overturn every government and so on. In reality, the pragmatic possibilities, mobilizational capacities are not the same as the desire to do that. But it is true that the continuation, basically, of the current situation with the war might objectively be in the interests of those who are currently holding power in Ukraine. That’s true.

Paul Jay

Because they also, I’m assuming, make money out of this. People get their taste of all these billions of dollars of arms sales back and forth. I’m guessing there are members of the Ukrainian oligarchy who are doing quite okay in the midst of all this, and they’re not the ones dying on the battlefield. The same goes for every war the United States has waged and then some.

Denys Gorbach

Yes, you have to… I’m trying to be careful not to overstate this because it’s difficult to place yourself in their shoes. To what extent does this seem to be fun, and does this become actually difficult to cling to the power with this whole war situation? But well, at least not being a specialist or not being a political scientist in that sense, I can say from my relatively unenlightened perspective that the ongoing situation does play into the hands of Zelenskyy and his team in terms of preserving power in their hands.

What happens after the war is less clear in terms of whether they will be able to cling on to their current positions or to cede them peacefully or less peacefully. And here, actually, we are coming to the typical post-Soviet power dilemma. Previously, it was already manifested in Russia. It was manifested in Kazakhstan. In some other places, once you construct an authoritarian regime, and currently, in fact, well, thanks to this war, Zelenskyy’s regime is quite on the way to becoming authoritarian, more than the previous ones, the previous presidencies. Once you construct this authoritarian regime in the post-Soviet space, at least, you have trouble securing ways of retreating. There is a systematic lack of possibilities of undoing your domination, peacefully. So you are either being violently deposed or you have to keep being this dictator because otherwise, there’s no way for you out of this.

Paul Jay

People are going to say there was a deal like this available and discussed three years ago, and apparently, there’s the story that Boris Johnson came. I think there were negotiations going on in Turkey, and they scuttled the deal. Once this thing is over, assuming we see the outlines of what this looks like, I would think people are going to say to Zelenskyy, what the hell did hundreds of thousands of people die for when you could have had this deal three years ago?

Now, I do want to add one more thing because I’m spending a lot of my time critiquing the Ukrainians, and I said something off the top, and I just want to reassert it so there’s no confusion. In my opinion, and I’ve looked at all the available evidence I can possibly look at, there was no imminent threat to Donbas. There was so no imminent threat to Russia. The Russian invasion of Ukraine was an out-and-out war crime. Period. Full stop. Under every single piece of international law.

Let me add one thing, which everybody knows that’s watching this, but I’ll say it anyway. The door to this was opened by the American invasion of Iraq, which was an absolute war done under a pretext, as was this one. Nobody suffered consequences. Bush and Cheney were never prosecuted as war criminals, which they should have been. Kofi Annan said this war was a war crime, but there were no consequences. President Obama had a legal responsibility to prosecute Bush-Cheney and did not, in fact, rehabilitated them and actually teamed Bush up with Clinton on a special mission to Haiti, as if now the guy that invaded Iraq is now some humanitarian. The door to all this was opened up by the Americans, and the Russians look at that and say, “Hell, they got away with that. Why can’t we?” It became a war of spheres of influence.

The realists, like Mearsheimer, a lot of people on the left want to quote, we don’t need to accept that world. That’s bullshit. This is a world of inter-imperialist rivalry, and we’re supposed to pick the horse we want to ride. That is not our job as progressive people.

Having said all that, to get back to where we are, what is the state of the Ukrainian working class now? Is there the potential, let’s say this agreement takes place, will there be a radicalization or, and this takes me to another point, one of the supposed big objectives of the Russians was the denazification of Ukraine, which, one, how about denazify Russia first and then talk about somewhere else, but set that aside. What has actually happened? Is the far-right, Nazi-ish far-right of Ukraine stronger or weaker? Now, three years later.

Denys Gorbach

Okay, I have several answers to this. So, first of all, just a quick note about the April ’22 situation because I feel it still remains a bit unclarified. I mean, up to you to cut it.

Paul Jay

I don’t know either. I read the mainstream press, and this is what people seem to say. It sounds like there could have been a deal, maybe.

Denys Gorbach

According to my best knowledge, what happened back then was Boris Johnson came to Kyiv and indeed talked to Zelenskyy. It’s not as if he said, “Yeah, I order you to keep fighting.” It was more like Zelenskyy and his team asked the British, “Are we going to have guarantees if we sign this agreement now?” And he said, “No, you’re not.” This is a different thing. It means that, basically, again, like today, it is the same dilemma. Either they sign, and the ceasefire is enacted, but then there are no guarantees, and that’s not something that they were willing to sign back then and not something that they’re willing to sign now. It’s different. It is about the West not being willing to extend their guarantees. So that’s a different light in which we can see that story.

Having said that, the working class, if you ask about the potential for mobilization, to me, it looks, in fact, rather low. Well, before the war, already, the working class… it was already legitimate to ask the question to what extent it exists if we understand class in the sense of not just category, not just the number of people working in such and such professions, but as a social issue, social fabric consisting of associations, trade unions, and horizontal/vertical links.

This is my research, what I was pointing out in the book. There is plenty of politics, obviously, going on in the working-class milieu, but it is very ephemeral.

For example, before the war, I was observing and then described a number of wildcat strikes. A wildcat strike has its repertoire of actions. It’s very fascinating that people already know what to do, who does what, and so on. But then, once the crisis is solved, the strike ends one way or another with a defeat or victory, and all the structures are dissolved. If there is anything resembling more or less permanent social structures, political structures, this is suspicious in the eyes of the post-Soviet workers because to them, this is what they call political, which is a bad word that is associated with corruption, with treason, and so on and so forth. There is this self-defeating dynamic that I was describing for Ukrainian workers, which self-sabotage by refusing to organize in a more durable way. To them, any durable organization would mean politics in the bad sense of the word.

Then when the war comes, when the Russian invasion comes in 2022, there is this hope. Well, there is, first of all, this surprise that the workers also, against all that we could have expected, in fact, do come, do go and join the army or join the forever volunteering efforts. Somehow, this strikes the right chord. There is this mass spontaneous reaction. This gives hope that, what you’re saying, that after the war, these structures will remain in place and will be serving the political purposes of the working class. So self-organization, not against the foreign army, but against the local elite.

Paul Jay

Well, let me say one thing. It’s not like the Ukrainian working class lack of class consciousness, lack of organization is something unique. We’re seeing that all over the world. Look at Canada, these threats of tariffs, Trump saying all these things about how Canada should join the U.S., and these big tariffs. Where is the Canadian working class having any independent position? Well, nowhere. Everything’s being expressed through the Liberal party and the Conservative party. The NDP, which is supposedly the Workers Party, is going to get demolished in this election. It is the same thing in the U.S. Where is there any real independent American working-class position? The UAW, one of the more progressive unions, the Auto Workers Union, winds up supporting Trump’s tariffs against Canada.

Denys Gorbach

Oh, yeah?

Paul Jay

Yeah. When I’m asking about the Ukrainian working class, let me say I’m in no way trying to be particularly critical of the Ukrainian working class. There’s only one real big difference at the moment about the potential between the Ukrainian working class and many other countries, which is that they’re armed. All the Ukrainian workers have guns now, and that’s not normal in a relatively advanced capitalist country. The oligarchy, the ruling circles, the government, I would think, when the dust clears, are going to be very discredited and have very little moral authority. I do return to a question I asked, which is it doesn’t have to go in a left-wing direction, meaning the Russians supposedly denazifying Ukraine. But have they actually strengthened the Nazis in the course of all of this?

Denys Gorbach

Yes. There are basically two fantasies about the armed working class. Either they turn their weapons against the elites. This is the Trotsky fantasy, anarchist, of course. The opposite scenario is that this will give a potential to what you’re saying for a right-wing coup or something like that. I would say that certainly not the first one, but probably the second one is likely; for now, I would say, it is not imminent.

Let’s put it that way because you and I might discuss how Zelenskyy is concentrating power, and we might not like his authoritarian tendencies. It remains a fact that his popularity among the actual working class, the actual existing working class, is quite high. Trump, if anything, made him more popular than ever with that recent exchange in Washington, DC. Which means that the far right, the Nazis, sure, they do exist in Ukraine. They do participate in the war on Ukraine’s side. Between the brackets, we can mention that part of Russia’s neo-nazis who chose the Ukrainian side and who are now fighting side by side with Ukrainian soldiers under the supervision of the Ukrainian secret service. I don’t know what they’re betting on. They want both Russians and Ukrainian neo-nazis to fight as much as they want. And with any luck, they will die. At least many of them will. So that might be a calculation. I don’t know. Maybe there are more sinister calculations. I don’t know about that.

The fact is that those of the far-right who have actual political ambitions or potential political ambitions in Ukraine, currently, I do not. It’s hard for me to envision them staging some coup or challenging the current authorities, the authority of Zelenskyy, because they do possess… yes, they are now being trained in weapons and so on and so forth. But politically, in terms of their popularity, in terms of the penetration of their messages, I mean, luckily, we are not there yet. They remain marginal in the sense of… I mean, paradoxically, or maybe not paradoxically, they are much more popular among the Ukrainian intellectuals, the public sphere, among the journalists, the intellectuals, than among the actual people, like the masses, so to say, the workers.

Paul Jay

Why is that?

Denys Gorbach

Well, historically, Ukrainian liberals were quite close to nationalists because of this history of subjugation. It’s a collaboration between the two political traditions that span the whole Soviet period. The composition it were for national Democrats, does not probably make much sense in other contexts. But in Ukraine, it means, yes, good guys who are for democracy, but also that includes nationalists, which is not evident everywhere, for other countries.

Paul Jay

I was reading an analysis somewhere that said while the Nazi far-right forces are not necessarily stronger in any official political way, Nazism, the Azov battalions, and such have become normalized, even somewhat heroic, because they have been fighting. Instead of denazifying Ukraine, this war has given them, in a weird way, more moral authority. Is that true?

Denys Gorbach

The normalization, yes, unfortunately, it happened. This process started even before that, before ’22. Yes, there was one big… how would you say it? The critical juncture was the Mariupol siege, which I don’t know why. To me, it’s just sheer stupidity. The whole state propaganda machine decided to concentrate solely on Azov. Although there were just as numerous or more numerous than them. There were Marines. There were other detachments that were not political.

Paul Jay

If I understand correctly, a lot of the left socialists joined the army and were also involved in that, no?

Denys Gorbach

In the Nazi-

Paul Jay

Defending and fighting the Russians in Mariupol?

Denys Gorbach

In the army, yes. But yes, precisely. Luckily, the army still does not equal all those elite detachments with neo-nazi political profiles. I don’t have the exact figures. It’s like a million people, I think now, in the Ukrainian army. On that wide background, we’re talking about, what, thousands? I doubt it’s even tens of thousands of Nazis. They are very prominent. Unfortunately, yes, now it is much more difficult, if not impossible, for example, to speak of Azov critically because everybody just forgot what they were, what they are politically, because now they are, in the popular imagination, only associated with the image of the heroic defender of the motherland. That is a problem. Their access to elite equipment and so on is probably a problem.

Paul Jay

We have lots more we can talk about. Let’s organize another session, but let me end with one question. What are you hoping for now?

Denys Gorbach

Well, I’m with the workers. Yes, I’m also totally behind this demand for peace, that is, cessation of hostilities without fighting for the 91 borders. I think that is something that everybody has already accepted, more or less in the depth of their heart, that this is not going to happen tomorrow or the day after tomorrow. Cessation of hostilities on more or less decent conditions, that is to say, guarantees that this will not start all over again tomorrow. This is the best thing that I can wish for this country because the endless war is not… I mean, it will end sooner or later, and it is better for it to end sooner than later because, every day, the economy and society pay a huge price. That being said, I really wish and I really hope that Europe is able to come up with some guarantees since we cannot expect any more from the United States.

Paul Jay

All right, thanks a lot, Denys. Hey, just tell people the name of your book. I forgot to mention it.

Denys Gorbach

Yes, the book was published in 2024, and it’s called The Making and Unmaking of the Ukrainian Working Class.

Paul Jay

Cool. All right, thanks. Thank you all for joining us on theAnalysis.news. Don’t forget, there’s a donate button up there. If you want more of this content, we need you to support us. Bye-bye.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | TuneIn | Deezer | RSS

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter

Denys Gorbach is a Ukrainian political scientist who studies the working class and national populism in Ukraine. He earned his PhD in 2022 and is currently a postdoctoral researcher at Lund University, Sweden.