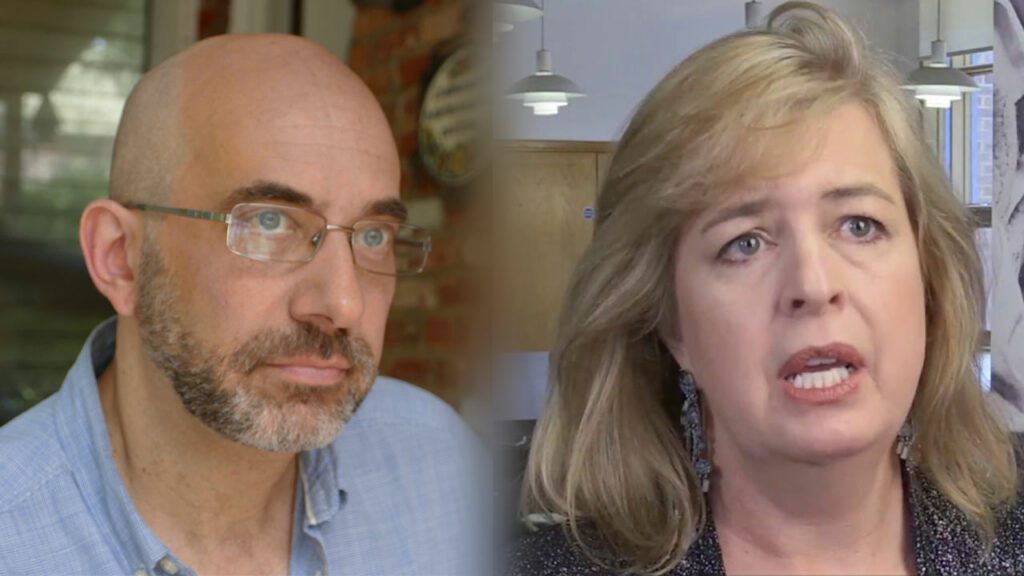

Katheryn Ledebur, of the Andean Information Network, based in Cochabamba, Bolivia, talks about the consequences of the on-going repression of the right-wing coup government. On theanalysis.news podcast, with guest host Greg Wilpert.

Transcript

Greg Wilpert

I’m Greg Wilpert, guest host for the podcast theAnalysis.news. The situation in Bolivia at the moment is

quite tense. On one hand, Bolivia is dealing with the coronavirus pandemic just as everywhere else, but

on top of that, about nine months ago, Bolivia went through a coup that deposed the leftist government

of President Evo Morales and replaced him with a far-right president Jeanine Áñez. Evo Morales’s

opponents, including the Organization of American States (OAS), accused Evo Morales of having

committed fraud in the election last year.

Morales had agreed to new elections though, but that wasn’t good enough, and the police and the

military intervened, forcing Morales and his vice president, Álvaro García Linera, to resign. Since then,

numerous protests in support of Morales have taken place, including a recent general strike in the

second week of August. Joining me today is Kathryn Ledebur. She is the director of the Andean

Information Network and a researcher, activist, and analyst, with over two decades of experience in

Bolivia.

Thanks for joining me, Kathryn.

Kathryn Ledebur

Thanks so much for having me, Greg.

Greg Wilpert

So let’s start with the political situation in Bolivia at the moment. I mentioned in my intro that there was

a general strike, so let’s start with that. And the situation of course, with the general strike and the

political situation that is, mixes with the situation of the coronavirus. And that’s one of the things that

actually came up in the news recently, that the government has accused protesters of hindering

shipments of medical supplies, and that could cause deaths.

But before we get into that, I want to just ask you about, well, who was organizing, who was behind the

strike, how long did it last? How effective was it? And how many people basically supported it? I mean,

was it a general strike? What was the situation?

Kathryn Ledebur

The general strike was quite broad through most of Bolivia’s rural areas. It was an amalgam of different

social movement actors, the COB (Bolivian Workers’ Center, the largest labor union in the country),

mining unions, rural farmers, coca growers from both regions, Bartolina Sisa (National Confederation of

Campesino, Indigenous, and Native Women of Bolivia). And there were non-violent blockades. In some

cases, there were sections of the road blocked with dirt, or hills knocked out. But for the most part, it

was a very strong protest against the changing of the election date for the second time, this time

without any legislation, and after the threats, the Áñez government made against the head of the

electoral court. The Áñez administration said, and later the electoral court parroted the same version,

that the elections scheduled originally for next week, September 6th, would occur at the peak of the

pandemic, and that there would be too many health risks to carry it out successfully.

This was something that the head of the electoral court just two weeks earlier had said was doable, and

that there was a clear plan. So there’s a lack of clarity of where we’re going here, or of following rules.

And people were very, very concerned, and began to block the roads. It’s also important to know that at

the same time, the intense political persecution has continued of social movement leaders, of hundreds

of MAS (Movement for Socialism–Political Instrument for the Sovereignty of the Peoples) public officials

at all levels, or former officials.

And the concern was building because there has not been a response to a request for dialogue on the

other side, flexibility, or any sort of retreat in this process.

It’s amazing that just last night the Áñez administration said they’re going to be loosening the public

health and safety regulations they had put in in response to the pandemic, which completely contradicts

their argument about why elections should be postponed. I think it’s key to understand that this

government does not want elections. This government has a lot to lose because of the poor handling of

the pandemic, corruption, and other scandals, so they seem to be seeking strategies to maintain

themselves in power.

It’s important to note that these blockades, which lasted approximately 10 days, began to evolve past a

request for moving up the election date and other measures, to a very strong movement to force Áñez

to resign.

It’s pretty important to remember that Áñez does not have a constitutional right to be president.

She appointed herself in an almost empty Senate chamber, and the excesses and the irregularities from

that point on have just continued to get worse.

Greg Wilpert

So before I dig deeper into the political situation at the moment, I just want to ask you about the

situation with the pandemic in Bolivia now. Recently, there was an article in The New York Times that

painted a pretty dire picture, saying that the death rates were something like 15 times higher in Bolivia

at the moment, or I guess it was at the height of the situation, which might have been in late July, early

August or so, way higher than they normally are.

And that people were having a hard time finding places to bury the victims, and that that there weren’t

anywhere near enough tests to find out what the situation actually is like. From what you’ve been able

to see, what is going on in terms of the pandemic?

Kathryn Ledebur

Well, I agree that the situation is quite severe and that the official statistics don’t at all capture the

severity of the crisis, and I think that there are several reasons for that. One is that the government has

no public health approach, has no real way or need to gather statistics.

It’s not as if there’s some sort of strategy to lead to a solution or containment of the pandemic. Finally

now, there’s greater access to tests, although test results take a long time. Finally, there is some access

to health care, but many, many people couldn’t get a space in the hospital when they needed one. Many

people went to the hospital, didn’t receive appropriate medical attention, and became a lot worse. So

we are beginning to relax the quarantine regulations, but when they lasted, we were in full quarantine

for two and a half months here. And that on the part of the central government, although they’ve

received hundreds of millions of dollars of international aid, there was no key policy or strategy put in

place, and no money disbursed to the local governments to carry out any of these efforts to trace

contacts or have any valid, coherent strategy to address this pandemic.

Greg Wilpert

Now, one of the things that you mentioned also was that the government itself had been accused of

corruption in relation to the pandemic response. Just tell us briefly what that is about.

Kathryn Ledebur

Well, there’s a wide range of corruption charges, from the phone company, to the hydrocarbons

company, and then a very key case of over 100 respirators that were purchased from Spain at three

times the going price that are still not functioning. They don’t have functional software, they don’t have

the elements that they need to work, nor are they appropriate for what is most needed, and that is

respirators within the context of an intensive care unit. And this is something that has been reproduced

in another case of the purchase of respirators from China that has just come to light. But also really

important to point out that millions of Bolivianos, several million dollars, were spent on anti-riot gear,

equipment for the security forces, at a time when the Áñez administration knew that the pandemic was

inevitable.

So we have a problem with priorities. You have cronyism in terms of the companies or the shell

companies that are chosen to buy this equipment and health equipment, and an overall scandal and lack

of accountability and transparency on where this massive amount of international aid is ending up,

although I have my suspicions.

Greg Wilpert

Yeah, your mentioning of the use of money for repressive measures brings me to the next topic, which is

precisely what’s been going on in terms of repressing of the popular movements in Bolivia, and the

election campaign that is supposed to be kind of happening, I guess. I mean, the elections have been

postponed, as we mentioned several times now. And of course, with the pandemic, it makes it almost

impossible to campaign.

But talk a little bit about what has been happening in terms of the repression and how the campaign is

going. And then, of course, what the candidate of the MAS, the movement toward socialism, which Evo

Morales heads up, but which Luis Arce Catacora is the candidate now, what does that look like?

Kathryn Ledebur

Well, I think we’re looking at a straight forward, blatant, aggressive political persecution, you know. At

the request of the MAS leadership, and in coordination with the MAS Congress, a law was passed

sanctioning this October 18th election date, and the protesting sectors retreated and voluntarily lifted

blockades.

But it’s important to note that even that didn’t slow what has been a consistent series of attacks on MAS

leaders, both social movement leaders and public officials, and trumped-up charges against some, very

public announcements of this. So we are going into an election period which supposedly will be free and

fair, although right now the only confirmed significant set of electoral observers are the Organization of

American States, and we’ve seen how questionable their electoral audit and some of the key areas that

they face are.

But right now, you have the presidential candidate, the vice-presidential candidate, key Senate

candidates, and other congressional candidates with terrorism, sedition, a violation of public health

charges layered on sometimes simultaneously in four different jurisdictions. And this is something that

the international community has yet to speak out about for the most part. We really have had silence on

the part of key actors, such as the European Union. The United Nations High Commission on Human

Rights put out its first report on human rights violations in Bolivia and highlighted this political

persecution.

But this idea that we are going to be able to have elections with this severe political persecution, it’s

very hard to imagine how that will turn out. Remember, at the same time that we still have these

paramilitary para-state organizations like the Cochala Youth Resistance, the motorcycle gang that works

sometimes in tandem with the police, but obviously with the permission of the police, and with links to

the Áñez government in Cochabamba at least, and the Santa Cruz Youth League, remember, they do a

Nazi salute, and this is another organization that is a para-state organization, and very violent. They

were implicated along with the police, in the shooting of 47 citizens in

San Ignacio de Velasco, Santa Cruz Department. That was two weeks ago. Still, some of these people

have not received medical attention, and have bullets, buckshot, and rubber pellets inside their body. So

we have these other actors where the state has deniability, but they have consistently since the October

20th elections, and at other times where key decisions are being made in Congress or in rural areas,

consistently harassed and threatened MAS supporters and other social figures with no legal

consequences.

Greg Wilpert

Now, it seems like two major questions are looming over the elections if they were to happen. One is

basically if they’re going to happen, and secondly, if they do happen, will they be fair at all, given all of

the repression that you’ve been talking about? But a third question that I’d like to raise, which is, let’s

assume that all of this does happen, that is first of all, that there is an election, maybe in October,

maybe later, and that after the candidate, Evo Morales’s candidate, is able to campaign properly, what

do you see his chances as, let’s say, factoring out the repression aspect, but in terms of just the

popularity of the MAS, and of Arce as the candidate, who I should mention used to be the finance

minister under Evo Morales, what does it look like in terms of their popularity at the moment in Bolivia?

Kathryn Ledebur

Well, I think that it’s important to note there was a significant sector of people who had previously

supported MAS that were discontented with Morales’s decision to run for a fourth term. But at this

period of time, when the right maintains a very racist, anti-indigenous, discriminatory discourse, and the

level of human rights violations, remember, we’ve had two massacres, and the consistent attacks, have

really torn people more in favor of the MAS government. It’s really hard to know. According to the polls,

most polls list Arce with a slight lead over Carlos Mesa, and other candidates trailing.

But within the situation of a pandemic, we don’t know how profound polls are. Their methodology is not

transparent. Polls always, and especially during this period of time, prioritize urban areas, and rural

areas are often a MAS stronghold.

So I think that there’s concern that MAS might win, and I think that probably in a fair and clean election,

they would. It’s not clear at this point in time when the votes are counted, and the way we’re going, and

with little what I would say independent or credible oversight. We don’t know what’s going to happen

and we don’t, you know. It’s an election with a very short turnaround time, October 18th, and if no

candidate gets a ten-point majority, a second round, and my assessment is if it goes to a second round,

all the candidates on the right will again jump into the same basket.

Carlos Mesa, the former president, has done very little to denounce human rights violations or the

impropriety of the current government. And I think there’s this idea that anything’s better than a MAS

return in the mind of the far-right. And remember that the Trump administration fully supports the Áñez

government. And we’re looking at a whole series of oligarchic figures that really want to return to

power. At the same time, you have an international community where the upper echelon seems to be

relieved that, you know, you really no longer have to take social sectors, unions, and grassroots

seriously, or include them as sectors in a debate or mediation. What I perceive is, and when I hear the

discourse from the international community, it’s very paternalistic, it’s very neo-colonial. Deciding

what’s best for people who were in government for a very long time, who have very clear proposals and

projects. And I think this is really a setback from the level of engagement that existed during the

Morales administration.

Greg Wilpert

I think it’s very interesting that you mentioned that Carlos Mesa is not denouncing the Áñez government

because clearly he probably is hoping that Áñez and other opposition candidates will support him in the

second round. Now, of course, one of the big weaknesses of the opposition seems to be precisely that

they’re so divided right? I mean, what does it look like? You mentioned that, of course, a winning

candidate could either win with 50% outright, but also if they get less than 50 percent, they have to

have at least a 10% lead over the next closest candidate, which, of course, gets more difficult if there are

too many candidates, if the right is fractioned among too many candidates. I guess my question though

is, how does it look for Carlos Mesa, what does he stand for, and what is he saying in his effort to win

over the population?

Kathryn Ledebur

In all fairness, I don’t know what he stands for because it’s been very fluid and he’s been very vague.

And, although in the October 20th elections he was perceived and presented as a middle of the road

candidate, a moderate, maybe as a version of a US mainstream Democrat for a US audience to

understand, he really has not held up to any of those principles. He’s often sided and gone to political

summits with the far, far authoritarian right, and I include both Áñez and Fernando Camacho of Santa

Cruz in that category.

So I think it’s so ironic that he pulled away from Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada in 2003, citing human rights

violations and an unwillingness to be complicit, yet he has not acknowledged the two massacres, nor

asked for investigations or respect for human rights. So I think that he’s kind of amorphous, and that the

apparent differences in the right are not as acute as one might think because their idea is kind of a

return to this pack, to the power that we had before MAS first came into office.

This idea of making an alliance and dividing up the state into different quotas, or different sectors, or

different ministries for parties to divvy up the spoils. And so you don’t have a clear set of proposals, you

don’t have a clear set of programs, and you have from no candidate besides Arce, a discourse of there

needing to be investigations, needing to be transparency, needing to rein in these paramilitary groups

that act with impunity at any time. Those are all things -proposals for reconciliation, proposals for

investigations, proposals for police reform, and for armed forces reform- no one’s putting that on the

table. I mean, it seems very much an election about capturing power, and, on the right at least, keeping

power away from MAS, and having their own little fiefdoms within the Bolivian state.

Greg Wilpert

I want to turn now to, for our listeners who haven’t been following the situation that closely in Bolivia,

to the coup, I mean, what brought us basically to the situation in Bolivia right now. As I mentioned

earlier, it took place last year. In October, October 20th, as you said was the election I mean, and then

eventually, formally what happened was Morales resigned. But let’s reconstruct briefly for our listeners

what happened more or less in a nutshell. That is, there was the election, and there were questions

raised about the election. What were those questions, and how did that then lead to Morales’s

resignation?

Kathryn Ledebur

Well, in the end, on October 20th, they had two things, they had a rapid count of the election that gives

you preliminary numbers, and that rapid count froze for a period of about 18 hours.

This is within the framework of a riot that had been calling fraud even six months before the election.

So that gray area of the count freezing, and then the assessment on the part of some sectors, and the

doubt that it created for international observers was a suggestion that the trend jumped dramatically in

favor of MAS, which is not something that is actually shown by the statistics. It wasn’t a significant jump.

And because of the pressure of all the other sectors, MAS agreed to an audit by the Organization of

American States of Electoral Results, and promised it would be binding, as none of the other sectors or

the other parties agreed.

Mesa, who had initially promised the OAS and had promised the United Nations that he would engage in

the audit, pulled a 180 and rejected it. So you had a period of time where an audit was being carried out

after elections.

The right and upper-middle-class Bolivians had blockaded roads in urban areas for a period of

approximately three weeks. But what you saw during this period was an escalation in the demand. So

first the right and the more conservative forces were demanding a second round in the elections. They

quickly moved away from a second-round in elections to demanding a new election. And after the

hastily presented OAS results, which we’ve now seen have some very significant methodological

problems, and I would say some other problems in terms of the interpretation of the data, though

certainly, this isn’t my area of expertise. But when Morales agreed to a new election on November 10th,

just 15 minutes after the OAS announcement, the sectors continue to attack MAS politicians, burnt

down their houses, and tortured some of their family members. But eventually, the Bolivian armed

forces suggested that Morales step down. We aren’t that far off from the dictatorships in the 80s to

understand that that suggestion, it’s not a suggestion.

It’s a clear violation of Bolivia’s constitution, a clear violation of international law. And what we saw then

was Morales having to go into hiding in the Chapare region before he left. And so even as the sectors

achieved Morales’s resignation, the violence continued, and they went after other key people in the

succession. The vice president had to flee. The head of the Senate, who was also a MAS person, had her

family threatened.

The head of the lower house of Congress’s brother was tortured and his home was burned down, all to

create a powerful way in which they could insert someone. Morales made many errors, but in this

period, he followed and kept his promises to the international community, and he did not bring the

armed forces out against the civilian population. As soon as Morales resigned, the military went out on

the streets the next day and started pumping bullets into people, we had seven dead.

There were retaliatory attacks on the part of grassroots supporters and MAS supporters, but, you know.

Several days later, the government passed a supreme decree guaranteeing, illegally again, impunity for

the security forces, and they began to pump bullets into the crowd in a period of violence that was

sustained, and that we haven’t seen since October 2003.

Greg Wilpert

Now, I guess the two main catalysts or incidents that brought about this coup were, first of all, the

accusations of fraud that were supported by the OAS, and then of course the military asking, or

supposedly asking Morales to step down, although I think it should be clear, as you suggest, that it’s not

really asking, it’s really more extortion than anything else. But let me just briefly get to those two

aspects.

I mean, one is the OAS count. That was really used, it seems, to justify the opposition’s maneuvers, and

also the military’s maneuvers to oust Evo Morales. But much later, the Center for Economic and Policy

Research had a detailed analysis showing that that OAS count was misleading, that, as you said, didn’t

lead to this huge jump that they claimed after the interruption. As a matter fact, just a couple of days

ago actually, there was a report that CEPR (the Center for Economic and Policy Research) released that

stated they finally got access to the official data analysis of the OAS, and it showed that they had a

programming error which caused the data to leap, and that’s why nobody was able to replicate it. And

as a matter of fact, MIT research researchers said the same thing, that the OAS analysis was faulty. So I

guess my first question in this regard is, what has been made of all of this? I mean, in Bolivia itself, have

there been any repercussions in terms of these analyses that were made outside of the country?

Have they reached the Bolivian people? Has anybody paid attention to it? Have there been any calls to

reflect on what actually happened?

Kathryn Ledebur

Well, I think there have been a lot of calls and this is something that we’ve gotten a lot of news about in

Bolivia, people are very concerned about it. With the high level of polarization, there are people who

dismiss it completely, some in the middle that will look at the data, and then some that felt from the

very beginning that the study was off, you know, the blip.

It’s interesting because I talked to somebody at the attorney general’s office who said we’re doing our

own investigation, and we found lots of errors in the OAS report. It’s interesting to note that they’re

prosecuting Morales officials, they certainly are not skewed in favor of MAS, but it really sets up this

whole dynamic where we have to look at something that was hastily done with a lack of clarity. And

then look at the ongoing role of the Organization of American States, and I find that so worrisome. You

have Almagro after this, although he had said that Morales should continue and finish his third elected

term through the 21st of January, as soon as Morales left, he said Morales was carrying out a coup.

He had very public meetings with members of the far-right, including Luis Fernando Camacho, a very

good rapport with Áñez officials, many of whom are also Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada officials, and very

clear bias. He even attacked, for example, when The New York Times presented another study, an

independent study critiquing the OAS electoral audit, attacked The New York Times, and insulted them

on his Twitter page. So you have this explosive figure allied with the far, far-right in Bolivia and the far,

far-right in Brazil and a lot of things, the Trump administration’s pick showing bias towards Bolivia, and a

lack of clarity. And then, you know, at the end of last week, his shocking intervention in the Inter-

American Human Rights Commission, refusing to renew the contract of Paulo Abrão, the executive

secretary, even though he had been reelected by the commission. So you don’t only see questionable

acts from the OAS in terms of electoral observation, but also an intervention in the Inter-American

Commission, which is supposed to be autonomous and move independently.

The Inter-American Commission, unlike Almagro and the greater OAS, has been quite critical of the gross

human rights violations, and has been quite pointed in their reports about them and their

denunciations. And I think that it’s quite telling that immediately after the news came out that Almagro

was inappropriately blocking and saying there were administrative denunciations, but being very vague

about it. This was simultaneously on the part of the Bolivian right a move to attack Abrão and to present

formal denunciations against him for not prioritizing things.

It’s really a part of this authoritarian far-right playbook that you see here in Bolivia with concerned

citizens denouncing blockaders and MAS officials for terrorism.

The concerned citizens in the end turned out to be the lawyer for the paramilitary motorcycle gang in

Cochabamba and other figures. And them being forced to prosecute, forced within quotes. And the

same thing happened allegedly with Almagro, there were other people who were concerned, and so he

is taking action, responsibility. But we see it over and over again, and we see that the moment it’s clear

that he’s pushing Paulo Abrão out, the security forces and citizen groups begin attacking all of the

people who have precautionary measures from the Inter-American Court, the violent civilian groups

storming into the Defensor del Pueblo’s office, threatening to hurt the Defensor and other employees,

kicking in doors, screaming racist chants, and other actions against officials who are withdrawing police

support.

So there’s a direct correlation between this blocking human rights investigations by Almagro and the

OAS towards the Inter-American Human Rights Commission, and at the same time using this as a way to

guarantee impunity for these far-right forces.

Greg Wilpert

It’s really amazing the extent to which Almagro, and we know that from lots of other cases, especially his

role in Venezuela, has been a factor for enabling the rise of the far-right in Latin America.

But let me just touch very quickly before we end on one other point that I raised earlier, which is the

role of the military. And one thing that, and this actually raises the question of the comparison again to

Venezuela, is that in Bolivia, the military decided essentially to side with the people who were trying to

overthrow Evo Morales. This is something that didn’t happen in Venezuela. And we all know why it

hasn’t happened that way in Venezuela, it’s because Hugo Chavez was a military person himself, knew

the military, and made sure that that wouldn’t happen if push came to shove.

Now, in Bolivia, what’s the role of the military? I mean, why do you think that they played along in this?

Was it that Morales didn’t pay enough attention to them?

Kathryn Ledebur

You know, it’s rather ironic because Morales paid a lot more attention to them than I thought they

deserved. They had salary increases, they received a lot of equipment, they received an increase in their

retirement to retirement pay with full salary. The other element in this that I forgot to mention is that

the police mutinied a week before Morales’s resignation, demanding the same benefits as the armed

forces.

I’m not sure whether the high command was offered money. The new high command certainly has, in

my assessment, personally benefited, although the armed forces have been in a very questionable

position.

It wasn’t a lack of attention to the military, but it was this inability to restructure or to make them a

citizens’ armed forces, and I think there are a couple of reasons for that. One, you have an old guard.

You have a lot of personal interest, you have temptations on the part of the far-right, or the suggestion

that the tide is turning and that there will be much less oversight, and we certainly see there has been

no oversight. The military high command promoted itself and other high-ranking officers without

congressional approval in violation of the Constitution. So you have a group that seems to want to gain

something, but you have the lower ranks of the police force and the military now wondering why they

made that decision.

They were put out on the streets in repressive control of COVID-19. Many of them got sick. The benefits

and the promises for the most part, beyond a small raise for the police, haven’t materialized. And

there’s a great deal of discomfort. So, you know, it’s clearly a coup, a textbook coup with this new kind

of Trumpian dimension of polarization through fake news. I read the other day on Facebook that I was

one of the people that supposedly was procuring underage girls to go out with Evo Morales.

You know, this wave of false information which has really affected public opinion. And denial of the

massacres, the Bolivian government says they shot themselves in the back of the neck. So we have this

element that’s facilitated a power grab and really authoritarian behavior that that is very similar to a

dictatorship.

And this new online movement and manipulation of the news kind of reinforces the authoritarian

behavior.

Greg Wilpert

OK, well, we’re going to leave it there for now. We’ve covered a lot of ground, but I think that’s really

great. So thanks again, Kathryn, for having joined us today. It’s been really great to have you on again.

Kathryn Ledebur

Thank you so much for having me.

Greg Wilpert

Again, Kathryn is the director of the Andean Information Network and a researcher, activist, and analyst

with over two decades of experience in Bolivia, specifically in Cochabamba. Thanks also to the listeners

for having tuned in to theAnalysis.news.

Which coup? There wasn’t any coup at all! You’re way too far from reality and seeing the international false facet of Evo Morales only. The 2019 elections were rigged so people did not like it and tried to kick Evo Morales out as he wanted to rule forever and ever like a true dictator. He escaped to Mexico then Argentina and made up the same story of the poor indigenous…I wonder who is using him in order to manipulate Bolivia and other leftist countries…