Max Rameau and Netfa Freeman argue that defunding the police could lead to more private police forces protecting private property, with even less accountability to the public. They say Community Control is a transformative demand that changes who has power over policing. On theAnalysis.news podcast with Paul Jay.

Transcript

Paul Jay

Hi, I’m Paul Jay. Welcome to theAnalysis.news podcast.

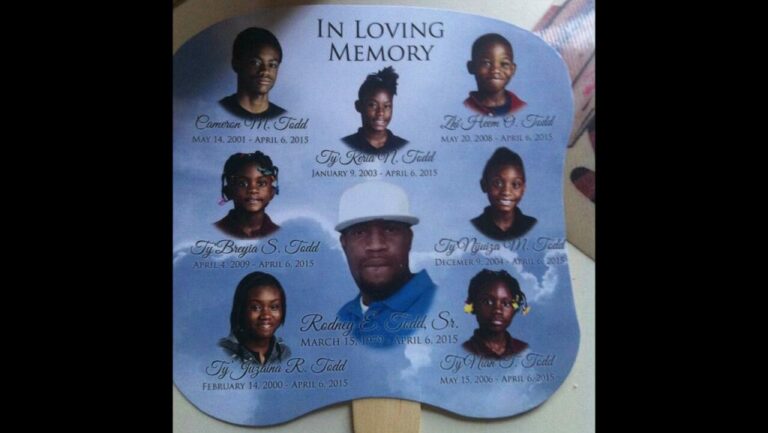

I was in Baltimore during the Freddie Gray uprising, after the brutal murder of Freddie Gray, when he was put in a police van, knocked around so much in the van—and beaten before he was put in the van—that his neck was broken, and he died. There was a large uprising from the community: thousands of people in the streets, led by young black activists, then young black workers, joined by white students. It became a serious spontaneous movement. In fact, there was very little organization: People just hit the streets.

The demands that came out of that movement—to do with arresting the police that were involved, first of all; then civilian review of police, civilians on disciplinary boards, more training of police, community meetings with police—well, all of that happened, and nothing much changed. The basic role of the police in Baltimore and most cities across the country is to act as a buffer between people who own stuff and people who don’t and to act as a hammer, especially in communities that are in deep poverty, which is much of Baltimore, but not all.

So what would have changed things? At the time, there was some discussion about community control of police, not just reviewing, not just oversight, but control. Now in the streets, a new demand has risen after the death of George Floyd. That demand is defunding the police, and it’s catching on in most of the cities where protests are taking place. It’s becoming one of the principal demands, but is defunding the police enough? Does it really address the problem?

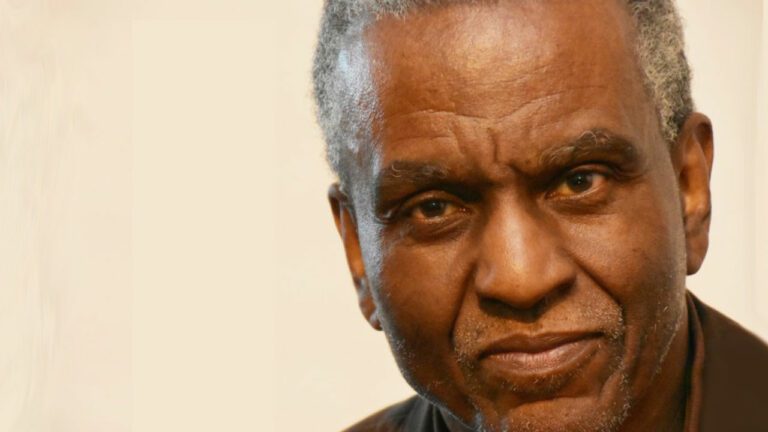

Now joining us to discuss this issue from Washington, DC, are Max Rameau, who’s a Haitian-born Pan-African theorist, a campaign strategist, author, and organizer with Pan-African Community Action (PACA), and Netfa Freeman, who’s on the coordinating committee of The Black Alliance for Peace and an organizer in PACA, as well. They’ve coauthored recently an article, and soon to be a book, titled “A Critical Analysis of the Demand To Defund the Police.” So, Max, kick us off.

This demand to defund the police has really caught on. You got people chanting it in cities across the country. You have even some city councils considering it. Bill de Blasio of New York, at one point said, he was supporting it—but how much, and what it actually means? But you think there’s real limits to that as a demand. What are they?

Max Rameau

If we remember back when Michael Brown was killed and Freddie Gray was killed—very close to one another, Mike Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Freddie Gray in Baltimore—there were the same kind of uprisings that we’re seeing today and the same kind of anguish and people being really upset with not only the specific case, but, overall, with the oppression that black people are facing in this country. And yet the demands that came out at that time were very different than the ones that we’re seeing right now.

The demands were: police say the slogan “Black Lives Matter,” which was an incredible cultural point, but it was not particularly effective as a demand; and, then, the other one was that police should be wearing body cameras. And so it really was giving—We were demanding as protesters, as organizers were demanding, that the State get the right to videotape us all the time with every interaction. And, then, they could keep those videos, and we’ve had all kinds of problems with those.

And now, fast forward 5 years: the demand has leaped from “repeat a slogan” and the police should be wearing video cameras, to abolition of the police. This is an incredible leap forward. So even though I have some concerns that this is not where we should end up, that’s what evolution really is about, that there are constant changes being made, but that doesn’t mean that this is the end. So I think, evolutionarily, this is a tremendous leap to have happen in a really, really, short amount of time. And that means, I think, that we are headed for some significant changes and some uncompromising movements in the very, very, near future.

In terms of what some of the limitations of it are: The real issue—at least as far as I’m concerned, our organization Pan-African Community Action—the real issue is not how much funding the police department gets, whether it gets too much or should get a little bit less or whether it should get none at all. And, then, what should the alternatives be? The real question is: Who has power, who is in control? And if we’re not in control, then it doesn’t matter if it gets a little bit of funding or a lot of funding. We’re not in control of it—and we want to be in control of it so that we have the power to tell whatever the safety forces are in our society and our community, we have the ability to say to them: “This is what we want you doing; this is what you cannot do; and if you do those things that we don’t want you doing, then you’ll be out of a job or you’ll be arrested.”

Paul Jay

Netfa, in Baltimore, it was so much focus on the police during Freddie Gray and there was almost no focus on who’s in control, who actually is—was in control of city council politics, of State politics. And obviously, I’m talking about the 1–5 percent who actually own stuff and really dominate the politics of the city. Are you finding a change in that now? Are people in the streets seeing beyond the police?

Netfa Freeman

Well, I think, to some degree, that is true, that people are seeing beyond the police; however, it’s not enough. It’s more than—just like what Max and we’re having to deal with the question of power and not abdicating the decision to those who have it, but also saying that we actually be able to have the control and the ability to implement and enact certain things—our own beliefs and our will and our plan, those kind of things—and then be empowered to protect that implementation.

And so while there’s a little bit of understanding of that, that the powers that be are the problem. Like, for example, and it is kind of easy to do—like, for example, here, a lot of the local in Washington, DC, where we are. That move that Mayor Bowser took to paint “Black Lives Matter” on the street and everything, that wasn’t lost on all these activists who’ve been trying to struggle with the administration here, the local administration, to recognize the people who have been killed in Washington by police in Washington, DC, and recognize that it is the local governments in DC that has blocked their ability to get any type of redress or information around the people who’ve been killed by police here.

So they know that those issues are—those gestures of painting things in the street are really just symbolic and meaningless. It might even have more to do with local and Federal contentions and Democratic versus Republican types of contentions than it has to do with really getting them some redress. We really have to have another type of transformation where we realize that unless we’re organized and fighting for the ability to have more transformative or power-shift kinds of demands and structural changes that will give us the type of ability to manage our own communities, then we’ll just be appealing to the very same powers that need the police and appealing to them for some type of redress or restructuring of the police, which won’t—that just won’t happen.

Paul Jay

Max, you’ve written in your article, “Community Control Over Police must be the central demand of this moment.” So what’s the basic thesis of why that demand is transformative?

Max Rameau

That’s the way that we shift power. So, again, our main concern is not with the exact amount of funding, although we do have opinions about how much funding one part of a society should get, public sector should get versus another. We think there should be more money spent on housing than there should be on arresting people or caging people, for example. But we really—the core issue there is not how much funding it gets, it’s who’s in control of that agency that does get the funding, however much the budget ends up being. And we think that by creating a plan and a way of achieving community control over police—a real practical, pragmatic, plan for doing that, which we have done—and we think we can get to community control, and this would be a way of getting to community control that is limited. In other words, it deals with the police, but it does not deal with some of these other entities of the government or the system as a whole.

But it is also very real and very tangible and creates a direct line from impact to people: low-income black communities in particular, and, then, inside of those communities, women and LGBTQ folks in particular. It creates a direct line from directly impacted people to the halls of power, even though it is the halls of power just dealing with the police. Our theory is that once people taste a little bit of what it feels like to be in control, to have power over the institutions that shape our lives, they’re going to want control after getting community controlled police—they’re going to want control over the school system; they’re going to want to have control over land, housing, farmland, public land; they’re going to want to have control over the economic system; they’re going to want to have control over everything. That’s really where we’re going with this, ultimately. But we think we can do that, given how important of an issue police brutality is right now, we think we can start with police brutality

Paul Jay

Netfa, the article connects policing to private property ownership, as I was saying in my introduction. You can see it clearly in Baltimore, but you can see it everywhere. Police are this buffer between people that own stuff and people that don’t. But you raise a very interesting question there—and this relates to some of the people who are talking about defunding and abolishing—at this stage of things that it might just give rise to private policing. What’s your point there?

Netfa Freeman

The analysis of it there is that the police—the emergence of the police, the creation of the police, or even the most—the earliest forms of police were around private property and the ability to protect that private property from those who didn’t have. And in fact, the earliest forms of property were African people, you know. And, then, the slave patrols and the private security agencies a little bit later are the earliest forms of modern—what we now know to be police. And, then, all— reading a little time later, transforming where they got together and realized, well, this could be that the State could run this institution. And, then, we also relieve those who are paying the private entities, paying for this protection. And they put the burden of that on taxpayers, on the public. And, then, now what that did, it didn’t change the essential function of the police, was just really—when we say systems, we’re talking about white supremacy, capitalism, and patriarchy as the systems right now. We’re hearing systemic change, but the systems aren’t being named. The police actually serve as occupying armies to protect that same relationship.

African peoples—as a result, black communities in the United States are domestic colonies. And so, what happens if we are looking at the neoliberalism and the track of neoliberalism, the tendency to privatize things and doing those kind of things really just falls into play with neoliberalism and austerity. Private police actually still exist. They’ve always coexisted with the public police. And now if we really just talk about defunding and abolishing the police, the ruling class will only revert back to their original formations of the forces that they used to protect it.

There’d be nothing—they would not just say, “OK, there’s no police.” There would actually be a different form of new police in the form of mercenaries. They may most likely be even more vicious because they don’t have any public accountability to which they have to adhere. The only law and only thing that they have to deal with are the bosses who hire them

Paul Jay

Max, as I said you linked this issue to the defense of private property, which I think is quite right. I once talked to a cop in Baltimore, and he said, “What do you want us to be?” And by “you,” I take it, he meant people who actually had power in the city. “You want us to hand out flowers, or you want us to be the hammer?” And clearly, the elites want police to be the hammer. They don’t like it when it gets so abusive that people rise up in response to it. But they want the hammer there because they want to contain the consequences of poverty, one of which is crime and domestic violence. They want that contained in the poorest neighborhoods.

But there—in Baltimore, there—most black families, most black people are workers. They do have jobs. Many live in relatively stable neighborhoods. And they’re also threatened by the consequences of the deep poverty and the crime that outflows from those sections of the city. And some of the elites in Baltimore, not much, but some, are black. Certainly the political stratum elites are black, and some of them have private property that they want to defend. So it’s a complicated question.

But even some of the activists in Baltimore were very big promoters of black capitalism, black private property. So it gets contradictory here. Does this suggest there needs to kind of be a more holistic approach as well, in terms of dealing, obviously, with the poverty, at the same time as the issue of community control of the police?

Max Rameau

I don’t think that it is that contradictory. I think it’s only contradictory if we’re only looking at one aspect. In other words, if we’re only looking at capitalism, but we’re not looking at white supremacy or patriarchy, or if we’re only looking at white supremacy, but not considering capitalism or patriarchy. And by the same token, if we’re considering only patriarchy but not the other two—capitalism or white supremacy—then that seems—can appear to be contradictory because of the high correlation between race and class. But really, the issue here is class. There’s oftentimes some confusion and overlap between the two. And of course, there are times when wealthy black people—black people in a certain class position—are also victimized by police brutality because race and class are conflated.

But overall, I think the real issue is that you’re going—anytime there’s a group of people, anytime there’s a class of people, who have a certain interest, and they feel like that interest—in order for them to maintain their privilege or maintain their wealth—they have to prevent other people from realizing their rights, then you’re going to have some form of police in order to keep those who are being oppressed from rising up against it. And that’s not only so with people who have money and want to continue to exploit us and can only do that if they have some way of preventing us from organizing or otherwise rising up. That’s also true with men who want to hold their position over women. And that’s why the police historically have policed women’s bodies and kept them from moving where they wanted to move and doing what they wanted to do with their bodies.

So, yes, I think all those things are in play and I don’t find it contradictory. I think we just need to develop a comprehensive understanding of the three aspects of the system—capitalism, white supremacy, and patriarchy—and how they all work together.

Paul Jay

Well, I guess what I mean by contradictory—or I mean everything is going to be somewhat contradictory—but in Baltimore, sections of Baltimore, one of their complaints about the police is they don’t get enough policing. I’m talking about black working class areas that look at the way white areas—there’s a relatively smaller white working class in Baltimore, so you’re talking about white areas that are more professional, somewhat more wealthy—get all kinds of policing. And in fact, Baltimore, if you’re white, is probably one of the safest cities in the country. The murder rate is almost one a day. It’s like 348 murders in a year, often. But less than 3 or 4 percent of that will be white people who are murdered. Sections of the black community—actually, it’s contradictory for themselves because, as you say, they are attacked for just being black, regardless of what their economic situation is. So they understand the problem of the racist structure of the police. On the other hand, they want to walk to the store without getting mugged because there’s such terrible addiction problems in the city and not being treated as health-care problems.

Max Rameau

Yes, I hear that. And thank you for clarifying that. Yes, so—of course, the fundamental root of what we call street-level crime, as distinguished from other kinds of crime, is poverty. So whenever you have poverty, you are going to have people who want to eat or need to eat and who need someplace to live and who need clothing and who are going to try to take something from those who have who are near them.

And the reason why really low-income black people, of course, don’t steal from higher-income white people is they don’t have access to those neighborhoods. And so they end up stealing from people who they are near. And of course, that threatens the day-to-day security of other low-income black people who are in those neighborhoods.

We think a couple of things. One is that the real way, if you want to solve those problems, if you really want to solve those problems—now, if all you’re trying to do is keep the people who have a little bit feeling as safe as they can, then you can do that without solving the underlying problem of poverty that compels someone to steal for food—but if you really want to solve the problem, then we have to address the issue of poverty. And that is, again, tightly related to the issue of private property. And then the second aspect then is even to the extent that we have a transition period when we’re trying to address the issues of poverty, but we’re not quite there yet, then we have to have a safety force, a security force—or what we now call police force or we think at the end, we’d have to change the name of the force—who can respond in a way that makes sense. Someone who is hungry and who is stealing because they are hungry must be put in a different position than someone who is stealing because they’re greedy. And one of them is considered a crime; and one of them is not considered a crime. So we want the forces to behave and to respond accordingly and to respond with some kind of care or with some kind of compassion and dignity for the person who is both a perpetrator in that moment, but also a victim in the broader sense of things. And we’d like to be able to do both in this society that we will control.

Paul Jay

Netfa, what does the model look like?

Netfa Freeman

That of community control of police?

Paul Jay

Yeah.

Netfa Freeman

Basically we’re talking about communities being organized so that they can come together in people’s assemblies or some type of forums and those who participate in it, and we’re trying to have some mass participation. There should be political education. We have to have ongoing political education so we’re understanding in detail a lot of the stuff that we’ve laid out just now, the implications of things.

And, then, those peoples’ assemblies would inform a community control board that would be randomly selected and be rotating, have some temporary term limits. And, then, that community control board would deal with the priorities and policies and the practices of the police—and, then, so, yeah, on the day to day. So that means they’d be able to hire, fire, determine who gets what the consequences are if something’s wrong, put all those things into being, and also determine how much money is spent, all that kind of thing. And, so basically, we are talking about a participatory democracy model where everyone weighs in and, then, randomly selects—much like a jury selection—people to serve on the control board and to execute the mandates of the people.

Paul Jay

Randomly selected or elected?

Netfa Freeman

We say randomly selected. We think it’s important, particularly in this stage, the way the country currently is. There’s too much disproportionate power and wealth to effect—that we see too much is in elections right now. They actually only control elections because of their money. So we don’t want a situation where—and especially, where—we’re dealing with a lot of working class people who might do anything. We don’t want it to be co-opted. And so if people are, you know, randomly selected—one, it also gives equal access to everyone no matter what. And so, yeah—so that’s basically why we say randomly selected.

Paul Jay

Max, doesn’t that allow for randomly getting people who are completely unqualified to do it? Just because someone’s a worker doesn’t mean they’re qualified to run this kind of a body.

Max Rameau

Oh, of course. If the argument is that randomly selected people are not qualified to make certain decisions, then we should today empty out all of the prisons and all of the jails because randomly selected, completely unqualified people, are the ones who give life imprisonment to suspects against whom there’s no physical evidence. They’re the ones who let people go, people who have all kinds of evidence against them. Random selection is the way jury systems in the United States are run.

And if that’s good enough to send someone—if those people are qualified enough to send someone to prison, then they’ve got to be qualified enough to say: “This is my tax money. And if I’m going to be paying my tax money, this is what I want the people who are getting my tax money to do.”

Paul Jay

Maybe the assumption should go the other way? Maybe juries aren’t qualified to be sending people to jail?

We’re down with either one. Like, if we choose one, if we say that randomly selected people are not qualified to be jurors, then I would accept that they are not qualified to decide how their tax money is spent. I would accept that—but I’d say that those same people can’t decide that. That means anyone who is in prison now, who was put in prison by some completely unqualified people, should be let out.

Paul Jay

Well, we know how manipulated juries get by prosecutors and especially, you know, so it’s not a good system, I don’t think there is any question.

Max Rameau

But the point is that they have the power in spite of not having any qualifications. Otherwise, they have the power to put people in prison. And they’re doing that right now.

Paul Jay

Yeah, and look, with terrible consequences.

Max Rameau

With terrible crimes—but here, we’re saying two things: One is that if they’re doing—if you’re saying—if this society is saying they’re OK to do one, then they should be OK to do the next. And the next is, actually, making decisions about how their own tax money is used. And if you’re—if we’re saying, then, they’re not qualified to do that, to say: “OK, this is my tax money, I’m going to pay someone to carry a gun in my neighborhood and give them the right to shoot people in my neighborhood.” If they’re not qualified to do that; then, they probably shouldn’t be qualified to vote either.

And I think there’s certainly a strong argument that people are “qualified” to vote based on the number of votes that Donald Trump has gotten. But I think we have to wipe the slate clean, which we’re down with doing also, by the way. But “whatever,” as they say, “was good for the goose, is good for the gander”—if it’s good enough to lock people up and is good enough to elect Donald Trump, then it’s got to be good enough to say, “This is your tax money. These are people who are interacting with you. You have the right to say, “‘This is the way they should be behaving, and this is the way they should not be behaving.'”

Paul Jay

Well, let me argue with you here. I think, it would be good to have a fight, an electoral fight: It keeps the organizing and the community going. I can’t see how this really works, unless it’s connected with a campaign to takeover city council in the cities to elect progressive slates.

What do police do? They enforce laws. Now, most of the laws are not created at the city level, and so, this is currently a problem of State and Federal. But at least as a place to get started, if you can start changing the laws that the police are going to enforce. I think it’s a critical piece of this, don’t you?

And if you have to fight it out—certainly with limits on—maybe if you can get some power at city council, you could say nobody can buy TV advertising. You could have very serious campaign-kind of spending limits. But doesn’t the community have to learn how to organize and win elections? Because in the final analysis, that is where power is.

Max Rameau

Well, right now it doesn’t look like that is working too well. We certainly, at least on paper, have the power to do that now. And yet even in areas where when the electorate of that area, that city or that State, is questioned and saying, do you want for example, do you think people should get security in their home instead of being evicted? Do you think people should get their Social Security money that is enough to live off of?—and things like that.

Even though they say that they believe one thing, the elections turn out in a completely different direction, and that’s because money actually controls the elections. So this would take the money out of the elections and take the democracy that, where now the power of the vote is given to someone in order to give a third party power over them. They would be able to exercise some of this power directly. And I think, it would—as soon as we recognize what having power meant in a real, tangible way, as soon as someone sat in the seat and made a decision and they saw that decision implemented, I don’t think they’d be at a stop there—I think the very next thing they would say is, “We need to take over the school board. We need to take over the city council. We need to take over all these other areas as well.

Paul Jay

I don’t have any argument about that. And we don’t have to keep arguing about the randomness.

But there are places—as terrible, on the whole, electoral democracy has been for people, especially for people of color. There have been recently some breakthroughs. And there may be, and I think partly because the technology has changed. The political system and the parties were never created, thinking that people could raise money without billionaires, without the multimillionaire class or billionaire class. This ability to raise money online, I think it’s changing things.

And there’s been some breakthroughs. I know, in San Francisco, because of the ability to have referendums that are binding, they’ve been able to create Medicare for all in the city; they’ve had free college education. There has been some breakthroughs in places. And I think we’re in a somewhat different time here, at least for now, as long as there still are elections. I mean, it may be, once elections become really effective, we’ll find martial law or something. I wouldn’t rule it out. But I think it does have to be pushed to the limits.

Netfa Freeman

I think that’s what we’re suggesting, is that we’re pushing, because one of the examples you cited about ballot initiatives and referendums are exactly what we’re suggesting for the community control of the police to win community control over the police. And the other part is us being organized, the communities being organized, which we really think is the essential aspect of it, that all of the people, particularly the most impacted, adversely impacted people, having formations that they lead and leading the whole struggle is really what transform things.

The other part about it, in terms of elected officials—the way this country is configured, particularly with the duopoly of the Democratic and Republican Parties, that those parties are and individuals are run as individuals who actually accept money and they’re not really beholden or accountable to anyone except for who can fund those campaigns. So right now, we’re suggesting that the participatory democracy model be exercised and that even if people do—like was suggested—opt for actually running candidates to go further, beyond the issues of the police, then we actually see an alternative model that we’re constructing, right there in the various communities, as opposed to the structural issues that we have with this so-called democratic system, which is beholden to money, to individualism, and to personality contests, here in the United States.

Paul Jay

Max, how does it work in communities or cities where the black population is a [majority], like in Baltimore? If you have a random method or even if you have an elected method, you’re likely to get a majority-black control commission or whatever. Do you have a name for what you call this, or just the community control commission?

Max Rameau

It’s the Civilian Police Control Board.

Paul Jay

Right. But if you’re in a city where the black population is a minority and if this is a citywide random or elected—you’re not likely to get a majority-black control. So how does this structure work?

Max Rameau

So our proposal actually calls to divide up the city into policing districts. And so there are several cities where I think we have a good sense of where those districts would be, but they could either align exactly with the existing political districts or wards or they could differ significantly. Those policing districts would be contiguous, and they would be reflective of the social and economic reality of that city. So, in Washington, DC, we could probably do it along the lines of the eight current districts; in Miami, we could do it close to the lines of the five districts—although I would do it a little bit differently from the ones that are there, for a couple of reasons.

And anyway, there’s a number of different combinations that can be used. And, then, we would call for a referendum. Everyone in the city, of course, will be voting, but each district would get its own ballot. The ballot would have the same question, of course. Do you want to keep your existing police force or do you want to replace the existing police force with your own community controlled force?

And those districts that vote for their existing police force, they like what they’re doing—great, keep them! You keep them. And, then, those districts, on the other hand, that don’t like what the police are doing in their neighborhoods—and you can imagine that in the same city, residents living in a wealthy neighborhood might like their police; and residents living in a low-income neighborhood might not like the police—then, those districts would vote independent of one another. So, in the same way that you have single-member districts right now in most cities, where those who are living in district 1 or ward 1 could vote for an elected official, and those who are living in district 5 or ward 8 could vote for another official.

And the votes in district 1 have no impact on district 5. And the votes in ward 8 have no impact on the votes in ward 2, because each, then, has independence. So at the end, we could have in a city—the city could maintain significantly run by the existing police department, but it could also, then, have one or two districts that are run by this new community controlled force. So, the way that would be handled, in terms of having not a high percentage of black people in a city and other cities like Madison, Wisconsin, or some other cities, is that the way the districts are drawn up would then reflect the social and political realities of those cities.

Paul Jay

So it would wind up community control of the district?

Max Rameau

That’s exactly right. That’s what we mean by community. Community would have to be smaller than a big city. You can imagine how unwieldy that would be in a city like Manhattan, for example, and all of Brooklyn or even in all of Washington, DC, for that matter.

Paul Jay

But there’s still going to be a command, isn’t there? The logic of the elites, at the very least, the logic of private property—they’re going to have to have a police force that can move from one end of the city to the other and organize resources and who’s getting what.

Max Rameau

Right now, even in the District, of course, while the District police, or in any city, the city police, are the police for the entire city. There are stations, and there are police districts, and police generally stay inside of their own district. They don’t cross across the district. They’re responsible for patrolling and responding to calls in their district. In addition, most cities have more than one police department. Washington, DC, has 33 separate police departments, and some of those police departments have jurisdiction over all of Washington, DC. Some of them have it only over a certain territory.

So, for example, the [National] Park Service only has jurisdiction over the Federal parks that are in Washington, DC. There’s a railroad police department that only has it over the railroads, and there are some police departments that have jurisdiction over a broader area than just DC. So the Federal Government, the FBI, etc., they all have jurisdiction over a much broader area. So going to a city and saying, look, these are the boundaries of this city, then, that would seem like that wouldn’t be a difficult thing to do.

Most cities also are encased inside of a county; and the county often has more than one city in it; and, therefore, the county police, generally speaking, have jurisdiction over the entire county. But, again, as a general rule, [the county police] don’t police inside of a city that has its own police department. So you can think of the city, then, would basically look like a county where it would have general jurisdiction over the entire city, but wouldn’t be responsible for policing over those police districts that have their own independent, community controlled force.

Paul Jay

Netfa, one of the things that impressed me about the document that you both wrote is how you’ve traced this issue of policing to private property and to the whole relationship of who owns stuff and who has power. How do you encourage more of that kind of discussion and consciousness in the movement that’s taking place now?

Netfa Freeman

I think it has to do with writing papers like this and, then, engaging the people around the ideas and having developed some kind of critical analysis of it. And Pan-African Community Action, we have what we call Assata Shakur study groups that are open to the community right now, and we had to revert to doing them online. But those type of things, and, then, having topics around where people are able to see more clearly the issues interconnected with community control of the police or policing, in general, or power, in general.

And so mass political education, basically is it, having things where people actually can exercise their own thought processes and not just be told what to think about things. And then we also have to engage in media campaigns, broad-based media campaigns. Going on this radio show or doing social media and, then, having people having to look at and be introduced to certain ideas is the first step in doing that. And, then, actually advocating for political education is an essential part of the movement.

Paul Jay

Max, when I was in Baltimore, with the Freddie Gray uprising, the elites were able to give a few concessions: They arrested the cops, charged them. There was a lot of talk about police reform. There was a Department of Justice (DOJ) investigation of the Baltimore police.

The report that the DOJ wrote, I thought, was actually quite good. It said that not a day goes by without the people of the poor communities and working-class communities and Baltimore’s constitutional rights are not being violated.

But there was no second act to the movement; there was no next demand. Do you think what’s happening now—do you see a second act, a third act? Is there a direction? Or, will there be some compromises and kind of get all subsumed, I guess, in the November elections?

Max Rameau

After the Ferguson uprising and right at the beginning and in the midst of the Freddie Gray uprising, we wrote a piece that is called “Forward from Ferguson.” We talked about what urban rebellion was and what role it had in the movement and what other parts of the movement were. And so we’re really looking at three phases here. The first is just raw outrage, and that outrage is what most people call riots: what we will call rebellions. And that is spontaneous expressions of outrage, not only at this specific incident of the murder of Freddie Gray or Mike Brown or George Floyd, for that matter, or Breonna Taylor.

But there was a there was a raw outrage. And that has a particular type of expression, and that’s by people who were really angry, but may not be that well connected to organizing or to what movement building means. By necessity, that, then, has to evolve into something else.

That something else is attaching to that anger a list of of things to which we are opposed: We are opposed to police brutality; we are opposed to mistreatment of people; we’re opposed to the people’s rights getting violated. And that, then, led to the second phase, which was mass mobilization. And mobilization is a particular type of thing. And, usually, it’s characterized by making a list—whether it’s one thing or series of things that we are against. And, then, we mobilize in order to put pressure on those who are in power, to tell them, “This is what we’re against, and we want you to change that to which we are opposed.”

And that’s mobilization, and it reached that very quickly. And the real question was for us, then, and remains today is, do we get them to the third level of evolution? And that is towards organization, and organization would not just be identifying those things that we are against, but clearly envisioning, articulating, and fighting for those things that we are for. Not just mobilizing against something of which we disapprove, but organizing towards something that we want to see come into reality.

And that is what we think would be represented by community control—not just saying , “We don’t like the way police handled this particular investigation, and we want them to do do it differently,” in some abstract sense, but saying, specifically, “Here is a system that we want to put in place that would put us in charge of the forces that are walking around our neighborhood, of the forces that are impacting our lives.” If we can’t evolve to the level of organizing up from mass rebellion, up from even mass mobilization, into mass organization, then we’re not going to be able to turn some of this raw anger into real changes that shift power—that take power from those who have it now and who use it to oppress us—into our hands so that we can free ourselves from oppression.

Paul Jay

Netfa, Max, thanks very much for joining me.

Max Rameau

Thank you so much.

Netfa Freeman

Thank you.

Paul Jay

And thank you for joining me on theAnalysis.news podcast.