There are major divisions in the E.U. about how to handle the pandemic and economic crisis, the domination of Germany and France, and relations with China and the U.S. Mark Blyth on theAnalysis.news with Paul Jay.

Transcript

Paul Jay

Hi, I’m Paul Jay. Welcome to the Analysis News, please don’t forget the donate button, subscribe button, share button, and we’ll be back in a second with Mark Blyth.

In an article in Politico.eu, Paola Tamma writes that European “‘strategic autonomy’ is the EU’s latest catchphrase, its label for the bloc’s push to increase self-sufficiency and boost its own industry in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. After the ‘America first’ motto and Beijing’s ‘Made in China 2025’ strategy, it’s the old continent’s turn to gaze inward but. Before they can implement it, leaders across the EU have to agree on what it means exactly.”

Tamma writes that some smaller countries “are scared that this push for greater autonomy is simply going to give Franco-German industry a new edge – and regulatory incentives – at the expense of smaller economies. A coalition of 19 countries who call themselves ‘friends of the single market largely’ abhor what they see as protectionism in disguise. “It’s a license to kill small and medium enterprises,” said one EU diplomat from this camp, which includes the Baltics, the Nordics, Austria, Benelux, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Ireland, Malta, Portugal, Poland, Slovenia, Slovakia and Spain.”

And to what extent is strategic autonomy directed at resisting U.S. pressure not to get too close to China? Tom Fairless writes in The Wall Street Journal that “the struggle between the U.S. and China for global influence has come to Europe’s gritty industrial backwaters, where China is steadily co-opting local economies, starting with their railroads. China overtook the U.S. as the European Union’s biggest trading partner for goods last year, a historic turning point driven in part by Europeans’ hunger for Chinese medical equipment and electronics during the Covid-19 pandemic. Increasingly, those goods are arriving in Europe through a new trade corridor consisting of railroads, airport hubs, and ports built with Chinese support, often as part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the giant global infrastructure effort aimed at binding China more closely to the rest of the world.”

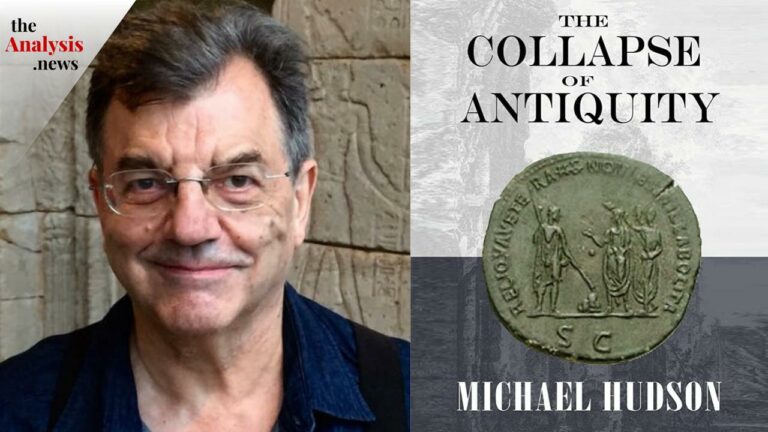

And he writes that with some alarm. Now joining us to discuss what European strategic autonomy is and how European governments are handling the current crisis is Mark Blythe. He’s a political economist at Brown University. He researches the causes of stability and change in the economy, and he also talks about “why do people continue to believe stupid economic ideas in spite buckets of evidence to the contrary”. I should add, he’s also a European.

So, let’s start with the situation in the EU. On the face of it, you’d think Europe would want to be more autonomous. What is this about and why are so many smaller European countries, it seems, so against it.

Mark Blyth

What is this all about? Hello, first of all.

OK, so what’s this all about? It’s about France. A few years ago, I did a project with some colleagues and we produced a book called The Future of the Euro, and a guy called Mark Vail, who’s a wonderful political economist, wrote this wonderful paper about France, and it’s about the whole of the EU after the euro crisis and the euro and all that sort of stuff, and it had the best title, which was “Europe’s Middle Child”.

So the middle child is basically never the favorite, the one who is usually ignored, and France, which was very much the ‘big’ country, particularly before Britain joined the then European Economic Community, was the leader of Europe and defined what it was. Yes, the Germans had the Deutschemark. Yes, they had the industrial muscle, but it was still West Germany.

France was the powerful country, and the Franco-German axis was what made things work. Maybe the Italians were part of it, but probably not. That all began to change in the early 1990s. Unification with Germany changed it further, the euro changed it further, and France began to lose its sense of self in the EU.

France loses its sense of self internally because of the same sort of processes of multiculturalism and immigration, that other countries are dealing with, but the loss of identity as the focal point of Europe really began to sting French elites. One of the things that they would talk about in that period was gouvernement économique – economic government.

So, you had this idea that the Germans had, which were rules, all the 60 percent debt to GDP, the 3 percent deficit, the 2 percent inflation. The ECB, which is rules bound with a big constitution. And all of this was basically the price of getting the Germans to abandon the Deutschmark. That’s basically why the EU ended up with all those rules.

But the French are interventionist at heart. They’re the ones that had ‘national champions.’ They’re the ones that tried to nationalize the entire financial sector under Mitterrand. They’re the ones that have always done industrial policy, regional policy, and even though their elites at one point changed towards this much more integrative, open capital space, competitiveness (mantra) that characterizes the E.U., that’s always been a latent part of, if you will, French elite political culture.

And what’s happened now in this moment, with the rise of China particularly, with the turn that Xi has given this, and then the rise of Trump…it’s given the European Union a wake-up call that you can’t just play hide and seek, that you need to have your own foreign policy. You need to have your own stance on things.

And this is becoming more and more apparent because essentially the way that Europe grows is the northern countries, particularly Germany and the Eastern European countries, the supply chains for Germany, sell goods to the Chinese and the Americans. They are export-driven. The consumptive economies in the south, essentially Italy, Spain, and particularly France, don’t do that. You don’t think France and global champions, you don’t see French cars on American streets, all that sort of stuff. So, they are much more dependent on local consumption, but those rules benefit the exporters and the inability to run deficits really hurts those domestic economies that are dependent on consumption. This has been a kind of structural fault in the eurozone for a long time.

So, what the French see with strategic autonomy, this new idea, is that we need to have industrial policy.

We need to have our own PPP. We need to have our own defense. We need to have all these things. We need to plan the economy more. We need to have strategic investments. We need to have our own thing, You can see the gouvernement économique, the old interventionist thing coming back, and in a sense, given the world as it’s become, it makes sense, but it flies in the face of everything that the EU is built on, particularly for those smaller states. So that’s essentially where this is coming from.

Paul Jay

Why do the smaller states think that with this kind of more industrial policy and interventionism and so on – and apparently the Germans are now warming up to this whole idea and there’s some big joint infrastructure programs now in the works between France and Germany. I mean, Germany already dominates the smaller countries of the EU and France gets a piece of that – but they think it’s going to get worse under this slogan, which nobody quite knows what it actually means in practice.

Mark Blyth

Well, let’s turn to what it means, first of all, for the Germans. It means we want to be able to sell our BMWs to the Chinese and not talk about anything to do with human rights and at the same time pretend we are the nice guys. For the French, that’s no longer acceptable because they don’t sell the cars to the Chinese and therefore they feel freer to point out that what’s going on in the west of that country is human rights abuses. So a lot of this is circling around Europe’s ability to act as a coherent actor on the European stage and have a position on China’s treatment of the Uighurs.

To answer what is our position on Hong Kong? At the moment, it plays second fiddle to trade. It’s a mercantilist agenda primarily driven by the Germans and their Eastern European supply-chain countries. But think about the smaller countries. Let’s think about Ireland. What does Ireland actually do? Ireland makes a lot of cash and has become a rich country literally by hosting IT firms, and there are real jobs, there is more than a brass plate. But historically corporation tax, stealing tax revenue from other European countries, is a huge part of it.

Holland? Exactly the same. One of the worst tax dodgers in the world. Latvia is money laundering for the Russians going out into global equities through Swedbank to the point that their central bank head was on charges a couple of years ago. So, there’s a lot of very different, shall we say, business models out there that would not benefit if Europe basically cut off its global entanglements and forced itself to concentrate internally on growing the domestic market, because that’s not how they make their cash either. So, for a lot of those countries, even the ones that are in the German supply chains, Romania, and all the rest of it, if you’re not selling BMWs to the Chinese, what exactly is your future? Because that’s what you’re asking these economies to do.

Paul Jay

Now, if I remember correctly, during the Greek economic crisis, which is not over, but during the depths of it, and in Spain when there were all these runs on what they call the peripheral countries, state debt and so on, a lot of it had to do with how Germany in particular had forced or created a situation where German products were so much cheaper than anything these countries could produce. They turned these countries into the consumers of Germany and the debtors of Germany. Why do these countries think that this slogan of strategic autonomy will make all that worse?

Mark Blyth

Well, because it could just be more of the same. I mean, what you’re referring to is a kind of vendor financing model. We buy your banks, and your banks then lend you the money to buy our BMWs, and then when people lose faith in your bond markets, you can no longer pay back the debt on the BMWs, because you don’t have your own currency. So, you need to do it through austerity. That’s the short version of how that worked.

You can imagine strategic autonomy if there’s another big bump in the road and the EU is more cut off from the world in some sense. It’s not clear exactly what that would mean. Let’s just say it’s less reliant on exports to the rest of the world, more reliant on consumptive growth. You could (then) tell a story where that would be better. It would be easier to accommodate an outside macroeconomic shock. It wouldn’t be quite as destructive on the periphery, but essentially it bespeaks something that is the love that will never speak its name, which is you’re going to have to give up a ton of sovereignty to do this. It’s not going to be OK to just have all these national governments and national budgets and you take 1 or 2 percent of GDP, and give that piece for the EU and they are a standard setter. If you’re doing this, you’re going to have to make actual political decisions about the allocation of investment, and once you start doing that on a continent-wide basis, why would the small and the weak think they are going to get what they deserve?

If you look at the way that the Juncker Plan, which was the last big investment junket that was spent in Europe after the financial crisis, €300 billion in investment, really about €30 billion levered up with various private sector instruments, et cetera. Huge amounts of it went to France, huge amounts of it went to Germany and Italy. So it’s the big countries that suck in this stuff. So, the periphery basically says, particularly the small periphery, what’s in it for us?

This way we can specialize. We understand what’s going on. If you’re small, you trade on taxes, you trade on a lack of transparency. You trade on particular niches in the global economy. If that’s all going to come in and it’s going to be big investment projects decided by the big countries, that’s kind of like taking us back to the 70s. We don’t want to go there.

Paul Jay

And what do you make of how the European governments are dealing with the deep recession, the pandemic-related economic crisis?

Mark Blyth

They are a bit like the Bourbons. What’s the line about the Bourbons again? “They had learned nothing and forgotten nothing.” So, there was a great deal of hoopla about the pandemic recovery fund, the Next Gen fund, but when you get into it essentially it is three years of 0.7 percent of GDP for the whole eurozone spread across the whole eurozone. So, Italy has got its hands on about, I think, somewhere in a region of about 40 billion that it’s going to spend in the next year. That’s not a lot of cash for an economy that size.

What’s happened because of the fixation on rules and the inability to do the type of expansionary programs that you see in the United States, in particular, is that millions of future taxpayers have left the south of the EU and gone to pastures new and may not come back. These are already aging societies with zero productivity growth become even older societies with zero productivity growth.

Italy is the real danger, the real canary in the coal mine here, because Italy’s debt to GDP is about 130 percent. It could go up to 160 by the end of the pandemic. And the basic rule of thumb is so long as the rate of growth in your economy is higher than the rate of growth in your debt stock and the interest rate on the debt, growth eats debt.

Olivier Blanchard did a piece in 2019 that showed most of the time the reason we don’t worry about debt is because growth is higher than the rate of growth in the debt stock and the interest rate. So, it doesn’t matter. It kind of solves itself through growth. Italy hasn’t grown in 20 years.

Italy has no effective growth model or political growth coalition to make it happen. This is why so much is resting on Draghi, right? Draghi, the magnificent, he’s come in, he’ll change the rules. He’ll spend 60 billion, 100 billion, and that’ll transform Italy. It’s going to take a lot more than that to transform Italy because transforming the oldest demographics in Europe is not something you can do very easily.

So, you’ve got this big bond market and an economy that doesn’t grow. That’s your euro crisis from the last time once again. Now the way that you stop this is the European Central Bank comes in and buys your bonds in the secondary market, but as far as I understand the rules, they can only do that to the extent that the whole eurozone is in deflation. So, what happens if you get out of Covid? Germany starts to recover. Maybe France recovers a little bit. Your small northern European countries recover quite well, and then on average, you’re no longer deflating. At that point in time, every hedge fund in the world will have shorts on Italian debt, because they know that the central bank now can’t buy it.

So, what’s going to happen is the yields are going to blow up back to where we were in 2011. And the thing is, they don’t have a printing press, so they can’t devalue the currency. They can’t default unilaterally. So, what do you have to do? Well, the other thing that Draghi set up called OMT – Outright Monetary Transactions – and now they have this big slush fund of money based, I think it’s in Luxembourg, called the European Stability Mechanism. It’s got half a trillion euros on it. In principle, it’s got that, but that’s not enough for Italy. If that bond market goes bust, Italian GDP multiplied by 1.6.

There isn’t enough money in Europe to solve that problem, and if the ECB basically comes in and panic buys everything, that’s also telling everyone yep they’re bust and there’s nothing we can do about it. So, there’s a huge liability sitting there and it’s not clear what the long-term strategy for solving it is. And what they’ve done so far, the Next Gen fund and all the rest of it really is insufficient to kick start the European economy, to get all of it, including Italy, on such a growth trajectory that the debt really is not a problem. So, I fear that we’re back to where we were in 2011.

Paul Jay

Well, it’s pretty crazy. The European economy is more or less the same size as the American economy, isn’t it? They have the resources to do at least the kind of spending that the various Biden plans are. And there’s no more risk of inflation in Europe than in the United States. We had this previous interview we did about inflation where you said, well, maybe if you have crazy people running Turkey, they could have inflation, but not in the U.S. and not in Europe, yet they still don’t want to come up with that kind of infrastructure and stimulus spending.

Mark Blyth

Well, you know, part of it is the persistence of stupid economic ideas. You do have this northern European angst about one degree of inflation leading to the Weimar Republic. So, part of that is hard wired in. But there’s a more sort of straightforward reason. If you are an export-dependent economy, stimulus spending is the last thing you want because you trade on competitiveness. You like to have a low rate of consumption in your economy, a high rate of savings, a high rate of investment, very stable labor relations, very sort of straightforward labor market transactions. You don’t want any volatility in this. And if you have a government that goes in and starts spending tons of money, well, wages start going up. People start randomly moving around labor markets, all of that growth and prosperity makes your BMW more expensive. And given that margins are thin out there in the global economy, you want to maintain your market share. So, if you’re an exporter, you know the type of big stimulus that you get when you’re you’re a big consumptive economy and you have your own printing press? Yeah, that’s an anathema to an economic area which shares a currency whose growth model is based on exports.

So, there’s perfectly rational reasons for the North and the Eastern European countries in particular to go against inflation, because what they’re really saying is if you raise our costs in any way, our business model is underwater. We don’t want that to happen.

Paul Jay

So what should be done? There’s a fundamental contradiction between the interest of the countries that are going to get killed by all of this and the ones that are winning. There’s nothing new about that. That’s been the story for some time. but if there were rational people in charge of all this, what would they do? Or is it that rational people are in charge, because they rationally want to make as much money as they can and this is the way to do it?

Mark Blyth

Yeah, rational people are in charge. I mean, nobody’s a dummy on this. People understand the problems. Brexit offers a nice analogy to think about this. So, Britain was never really in the EU. They were never going to join the euro. They had a seat at the top table that could veto anything that they didn’t like. They could offer the legislation they wanted and form coalitions to get it done. In a sense, they had a fantastic deal, right? You have free market access for 60 percent of your exports, blah, blah, blah, and they decided to not to stick with that. OK, all power to you. Now, a lot of this is being covered up by the costs of Covid, but pretty soon we’ll begin to see what the costs of Brexit are.

We already know anecdotally things like the entire Scottish shellfish industry is now dead because what used to happen was nobody in Britain eats lobsters. They all sell them to France, and when you have 100 percent market access in the EU, you stick it on a truck in the north of Scotland, you pack it with ice and you belt it down to Dover and it’s on the table in Paris a day later and it’s still fresh. The minute you put up a border with border checks, you destroy that industry. Now, Brexit is an attempt to take two economies, the EU and Britain, that were integrated for 30 years, and you’re unpacking this, right?mNow, try unpacking the whole European Union where everybody shares the same currency, but everybody has a different debt market.

There are multiple models of how you generate growth and income. Some are very good, relatively speaking, such as the German and some of the East European ones. Some of them are just not. For example, Italy hasn’t grown in 20 years. So, what exactly is the solution? And we know part of the problem is that the euro is the Hotel California. Once you check-in you can’t check-out without destroying half of national savings. This is why even Italian populists and French populists now are not pushing on getting out of the E.U, but it’s not clear how you solve that fundamental problem.

You’ve got three big economies, Spain, France, and Italy, that are driven by domestic consumption, that have been living under a regime of low growth and tight budgets for 20 years, and they’ve accumulated a shit ton of debt. Their investment has fallen off a cliff and they’re not doing well economically. Then you’ve got the countries in the north that basically have done really well through globalization, China’s stimulus post-2008, American growth post-2014. They’re fine and they like it how it is, and they don’t know how to fix that other problem because their growth model is the opposite of that. That’s it, and nobody has a good solution to this other kick the can down the road, hope for the best

I mean, you could imagine that, to go back to the earlier point, strategic autonomy is in a way a sort of attempt linguistically to recognize that problem and say we need to balance it out so that the whole eurozone grows more like one national economy. We rationalize investment and we look after the periphery, et cetera, et cetera. That brings us back to the old idea of gouvernement économique, economic government, but all of that is still anathema to the actual bits that grow. To the Dutch, to the Germans, to the Finns. So, it’s just not clear how you play this out.

Paul Jay

Well, maybe the way they play it out is they continue beggar thy neighbor meaning France and particularly Germany, and they say, well, too bad to the poor, smaller countries of Europe because we’re going to make our money exporting to China because it’s a hell of a lot bigger market than you are, and if that butts up against the U.S., that doesn’t like the fact that China has just become the biggest trading partner of Europe. Well, we’ll have strategic autonomy because we want to stay rich and get richer. We’ll do that exporting to China and we’ll play China and the U.S. off against each other and, screw the rest of poor Europe.

Mark Blyth

That may be one way of playing it, but I think the way that they’re actually playing it is slightly different. You notice that this time around, in comparison to 10 years ago, no one is screaming for expansionary austerity. No one is saying that we should all cut our budgets in the middle of a recession because that will actually be good for growth.

They tried that and it was a train wreck and it brought a collapse of multiple party systems across the EU. The people who run the Commission and other places, they’re not idiots. They’re pretty smart people, and they understand that if they try this again, it’s over.

The two largest parties in Italy, and this is simply because the party system is so fragmented, are the soft fascists, the Lega, and the Fratelli d’Italia, the actual, no honestly, we are a fascist party and we’re not apologizing for it. You put the two of them together in coalition with Forza Italia and a couple other parties and you have a government. That scary, right?

If you think about Germany, everyone’s high on the prospect the Greens are now the largest party, but you’re also looking at a complete meltdown in the CDU along the lines of what you’ve had with the SPD, and it looks like the Alternative for Deutschland are sneaking up in the polls again. So, there’s very little margin of error for getting this wrong. If you go on a big austerity diet after this one, it’s game over in terms of democracy in many countries, and I think everyone really knows that. So, what they’re doing, sotto voce, with very soft voice, is kind of forgetting about the fiscal rules, forgetting about debt brakes, and saying oh yeah we’re going to renegotiate (the rules).

You mentioned Blanchard earlier in another conversation we had. We talked about Olivier Blanchard. Yes, he’s talking about inflation, but he’s also talking about why don’t we just forget these fiscal rules? Why don’t we have a wisemen council of people like me and we can talk about it? I don’t think that’s a very good idea, but nonetheless, the idea that, you have 60 percent debt to GDP, and that’s a good thing. We’re kind of past that. So, what you’ve got is a de facto flexibility in policy now that you didn’t have before, and that’s an improvement. Is it enough to solve the problem? Probably not, but it gets you to a less crappy place.

Paul Jay

This Wall Street Journal article I quoted in the beginning. He talks about China investing in Eastern European railroads, uses the word co-opting. Whether you’re coopting or not, nothing is stopping the Americans from investing in East European railroads.

Mark Blyth

There’s nothing stopping the Europeans investing there (either). I mean, the reason that China is able to do this is they walk in with a bag of cash and say, hey, how about we build you a whole high-speed rail network and we build a few highways and we’ll reinvest in your ports? And you look around places like Trieste in the Adriatic and go, well, nobody else is doing it. So, if the EU is unable to do this, then, of course they’re going to take the cash from wherever they can, and that’s pretty much the card that China has dealt with.

Now, are they building their own routes to basically bypass sea routes and all the rest of it? The long-term goal of Belt and Road is twofold. We keep accumulating American paper assets because we’re a large exporter, even though now we’re a very big consumptive economy as well. And we hate doing this because all it does is license American bad behavior because you can never get out of the dollar. Well, we’re going to do three things. Number one is a digital renminbi so we can bypass American clearing and just pay people straight with our currency, and so long as they’ll accept that we should be fine. We don’t seem to be macro-economically idiotic. So that should take a bite out of it. Secondly, we want to turn all these paper assets into real assets.

We’ll take the surplus we generate, and we’ll build a port in the Adriatic. We will even go to Germany and we will repair the locks on the canals that they’ve allowed to fall off because they’re so obsessed with the black zero and budget balance that public investment has collapsed. So we’ll basically ‘cash bomb’ investment all over the place because your idiotic rules have deprived you of the ability, or language to even do this, and we will basically turn Belgrade in our direction. They will be ordering Sinovac. They will say, to hell with you and your procurement process. Now, is it because China just wants to cause trouble? No, their bigger thing is, point three of this, if you put all this together with a high speed network across western China, across transcaucasia, and hooking up basically with Eastern Europe. You can bypass the American fleet.

You don’t really have to worry as much about getting that choke point out there in the Pacific. If you can source your green production of foodstuffs from leased land in Africa and you can basically put that on transports, which then dock in the Adriatic and ship it the other way. Why would you not do so? So of course, they are thinking long-term, they are thinking strategic autonomy. They’re just doing it in Europe. You want to know what strategic autonomy looks like. That’s what it looks like.

Paul Jay

And what’s wrong with that?

Mark Blyth

What’s wrong with that is basically it causes the United States a huge amount of trouble.

Paul Jay

Well, what’s wrong with that? There’s nothing immoral, evil. Whatever is going on domestically, in terms of the relations they are having, certainly with Europe, and, yes, maybe they get some advantage. They get some of these countries into debt and so on, but compared to what the U.S. has done, both militarily and economically, it seems relatively benign. They’re just trying to grow their economy.

Mark Blyth

And at the same time, we now have the problem whereby Western firms, if they say anything at all about the condition of the Uighurs in the west of the country, or if anyone points out that the cotton in your t shirt comes from there, or actually my favorite one, 50 percent of the plastics in photovoltaics come from that region, everybody who loves solar, you’re basically supporting the repressive regime in west of China.

Paul Jay

So that’s basically where we are. Well, anyone that buys American products is also supporting the regime that supports Saudi Arabia and Israel and go on from there.

Mark Blyth

Hey, I get it, right, but from the European point of view and the point of view of European firms, this is a landmine. Who am I pissing off by doing this? Do I really want to be the one who wants to be in on China, when all of my consumers decide that this is the worst human rights thing (record) in the world? So there are costs and benefits to doing this. It’s easier to go with the U.S. This is the long-term ally.

The United States, when it makes a terrible mess, tends to make messes that they don’t care about, like Iraq and Afghanistan, rather than doing things that we putatively care about, like western China. So, there’s a kind of competitive bidding up of ‘my human rights abuses are worse than your human rights abuses’, but at the end of the day, what Europe wants with strategic autonomy is exactly what you said. They want to be able to sell BMWs to the Chinese without getting called out on human rights, and they don’t want to piss off the Americans enough that they lose the security guarantees because ultimately they’re still getting their gas from Russia. They’re not in a nice place.

Paul Jay

And the reason why “we” care about human rights abuses in western China is because Western media has made us care about human rights abuses in western China and not human rights abuses in all the countries that are American allies. I’m not trying to prettify what China does. This kind of narrative. Americans do bad things, but for good reasons, whereas China does bad things for bad reasons. It’s been a BS narrative for a long time.

Mark Blyth

It depends how you look at this. China gets a lot of crap for the surveillance society and all that sort of stuff. Right. But one of the most surveilled societies in the world is Britain. I think Britain has more cameras per head than anyone else. So, it depends on which metric you choose, but at the same time, I mean, honestly, are we trying to say that China is therefore as free a society as Britain?

Very few people in Britain get knobbed off the street by the police and disappear. You don’t really take your billionaire class and defenestrate them publicly and jail them for months. There’s basic security of property rights, all that sort of stuff. This is a regime which has taken a turn, which is antithetical to the way that Western economies work, not to fetishize democracy or anything, but when it comes to basic things for capitalism, like secure property rights, you don’t have that in China and you’re increasingly less likely to have that. So that weighs heavily on the European scale as well. Americans, we have problems, but if you put your money there, you can get it back out. You put your money there [in China]. You’ve no idea what’s going to happen to it.

Paul Jay

Of course, if you’re China and want to buy an American company, they may use national security to stop you from buying it.

Mark Blyth

Absolutely and they’ve been doing that for years. I mean, people think this is new. The Foreign Investment and National Security Act came out in 2007. You’re old enough to remember this as well. Remember the Cold War with a whole slew of restrictions called COCOM [Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls], which stopped us selling stuff to the communists. We’ve now swapped this out for FATCA [Foreign Accounts Tax Compliance Act] on finance and for the whole export control regime that goes on for tech. Same shit, different smell.

Paul Jay

Well, I guess part of what I’m saying is whatever you make of the morality in all of this, and I don’t think there’s much morality on when it comes to human rights on the Chinese or the American side, although granted, domestically, if you’re not black and living in a poor part of America, you do have some democratic rights. If you are living in a black or Latino.

Mark Blyth

You are completely policed in an authoritarian manner, absolutely.

Paul Jay

And probably killed in a way that may happen in China. Anyway, all that being said, I don’t think the Europeans actually really care that much about human rights anywhere when it comes to their trade and finance policy. So, the U.S. is going to have trouble winning this one. There was a document by BlackRock, the big asset management company, put out a couple of years ago, and it said the countries of the world will have to decide what side they’re on, U.S. or China. I don’t think that they’re going to do it. Certainly, Europe is not going to say, oh, we’re with the Americans against China. I don’t see how the Americans win this rivalry.

Mark Blyth

So, there’s a thing in the world called international relations theory, which is this product of the American academia, which essentially asked ‘how do we think about how good we are in the Cold War?’ And they had these distinctions about what countries did under balancing conditions in the global economy, in this anarchy, and I always thought this is quite good. So, the first one is, you balance against them. So, you imagine European and the United States balancing against China, and the other one is bandwagoning.

So, you jump on the bandwagon because that’s the way the train is going, but there are also two others which Europe are really good at. The first one is transcending. That is to say, you just pretend shit doesn’t happen. It is really good at pretending things aren’t happening and the other one is hiding. You just basically hide. So, the European strategy is always been transcending and hiding and they are being forced to choose between balancing and bandwagoning. It’s very hard for them to bandwagon with China fully.

It’s just a very different system. And if your economies grow, think through things increasingly like the protection of intellectual property rights, the rents accrued from patents, all the rest of it, you’re getting into bed with a regime that’s never going to play well that way, whereas you will with the Americans.

On the other side what really makes the advantage for China is if China credibly commits to doing something about climate in a serious way, they probably will because they have that kind of authoritarian advantage. If the Chinese Communist Party says next year, no diesel cars next year, no diesel cars.

We in the United States have this terrible, terrible system called democracy, which has its advantages. There’s a piece I did in Foreign Policy recently with Thomas Oatley called the Carbon Coalition that talks about this. If you drum up the Republican vote, basically, it’s just states that have carbon as their business model. Extraction, refinement, all the rest of it. Climate change is an existential threat to North Dakota, to Texas, to these states, and they’re doubling down against climate change. They’re putting taxes on wind investments when Biden’s plan is trying to give them more investment incentives and stuff.

And China just looks at this and asks ‘what are you doing?’ You people are dancing around physics. This is nonsense. So, America’s weak point is if four years time we vote in Trump 2.0, and if you do that all the climate stuff goes out the window again. At that point, America has zero credibility in climate going forward for the next 20 years. (Meanwhile) everybody who actually accepts that this is a real thing then bandwagons with China because they’re the only big player that matters, and America loses its technological edge on that side as well.

And that to me is the big worry, and it’s also what worries the Europeans. They are deeply concerned that America cannot actually cash the checks that it’s signing just now when it comes to commitments on trade and climate because of it’s domestic politics.

Paul Jay

And, well, China’s got the other problem, which is they better get serious about coal because right now coal’s expanding, not decreasing in China, and they won’t have much credibility on climate either.

Mark Blyth

No, absolutely, but Xi did come out, for what it’s worth, about six weeks ago and say no more coal Belt and Road. Stage 2 no more coal. We’ve got to get past this.

Paul Jay

Well, if they do that, then the equation you just elaborated really kicks in because even the Biden plan is pretty weak on climate in spite of all the rhetoric. I did this interview with Bob Pollin and we went through the infrastructure plan and he thinks only about a third of that plan has anything to do with reducing carbon emissions, and then you look at building retrofitting, which is one of the easiest.

Mark Blyth

Big easy ones right? It’s a third of it. Like just do it right. We know how to retrofit buildings.

Paul Jay

Well, they’re targeting two million homes. I mean, two million homes is not even a midsize city. I guess maybe it is a mid or smaller city. I mean, it’s not a serious commitment. Two million homes for retrofitting.

Mark Blyth

But given everything else that we’ve spent money on in the past year and a half, it’s a small line item, but it’s better than denying that it’s not happening. It’s a foot in the door that you can build on. That concept matters at that level, but the difference, again, is China.

I can conceive a world in which they just say 2030, no more diesel. That’s it. No more diesel. You get caught driving a diesel, you’re in trouble. No negotiation, and I’m not saying that I applaud that, but that’s a credible commitment. Whereas if you’re just going to flop between insufficient and denial, then you have no credibility at all.

Paul Jay

Well, let me just say that it’s not much of a democracy. Let’s say the formal veneer of democracy, yes, but it’s not much democracy when big money so controls the outcome of elections, including fossil fuel money and so on.

Mark Blyth

Yeah.

Paul Jay

You know what’s democratic about having a policy that’s going to destroy civilized life?

Mark Blyth

Throw in gerrymandering, throw in all the rest of it. Yes, absolutely. We should downgrade ourselves very much on where we stand among the world’s democracies, no doubt, but at the end of the day, to return to Europe. You’ve got a semi-functioning polity at least half the time and you’ve got relatively secure property rights, and if you put your money in, you can get out.

On the other hand, China may make a credible commitment on climate, which is tremendously important, but everything else is kind of orthogonal to the way that you organize your economy and society. It’s very hard to get in the bed with it. So, you are stuck in the middle.

Paul Jay

All right. So, I have a proposal to you, another session, another day, because when we reach the conclusion of these kinds of conversations, the conclusion I reach is there is no solutions for these things under capitalism, certainly not the capitalism that exists, and I don’t know what other capitalism there is. I mean, this is what it is, because this is how capitalism evolves, and some form of socialism.

Can we get there? That’s a whole other story, but these problems that we’re reaching, our conversations end, whether it’s Europe, whether it’s climate, whether it’s China, like everything ends with it, with the phrase it’s not clear how they’re going to do this. Well, I think it’s not clear how they’re going to do this because they can’t.

Mark Blyth

Well, I put it a different way, and I’m happy to have that conversation, all you need to do is spend five minutes in a faculty meeting with other people with Ph.Ds to realize the collective decision making by people who think they know what they’re doing can be a total disaster.

Paul Jay

I just want to talk about academics.

Mark Blyth

Well, who the hell do you think are technocrats?

Paul Jay

OK, I was just going to say they’re the worst in the world.

Mark Blyth

Yeah, and what about all the technocrats that have brought us, like so many good things over the past several years, like central bank independence, chronically low inflation and low wages and massive inequality, they’re the best and the brightest from the best universities. When it comes to sort of, let’s all have a plan and stick to it. I’m deeply skeptical.

Mark Blyth

Maybe part of the human condition is just muddling through that we somehow managed to get somewhere. We’re not dead yet, and that’s basically the best we can hope with. Because I just get deeply fearful when I hear and the only way to do this is socialism, because it’s this big, empty signifier that I don’t know what it means. I don’t know what it contains, and it usually contains people like me deciding really big things that they don’t know enough about to actually make those decisions. So, I just get nervous with that one.

Paul Jay

All right. So another day.

Mark Blyth

You got it.

Paul Jay

OK, thanks very much, Mark. All I was going to say is I didn’t even go to university, but I have been in some of those meetings with academics.

Mark Blyth

Right.

Paul Jay

They are almost a different species for how bad it is to try to get an outcome out of one of those meetings.

Mark Blyth

What do you think Gosplan was? It was a bunch of academics with slide rules. No wonder it was a disaster.

Paul Jay

All right. We’ll fight this out another time.

Mark Blyth

We shall indeed.

Paul Jay

Because I think we are now on the verge, at least theoretically, of having forms of socialism that don’t become those bureaucratized overly centralized and often police state. So, I don’t think that’s inevitable.

Mark Blyth

The best book on this is Fully Automated Luxury Communism, which is basically techno-utopia for the left. So you might want to have a look at that one and then reflect on the fact that if you take the social goals out of it which people like us would agree with, all you’re left with is a kind of like Hollywood Silicon Valley AI (that) will solve everything. Nobody needs to work, and I don’t believe that in a normal world, so I don’t see why I should believe it in a left-wing one, but there we go.

Paul Jay

All right. There we go. All right. Thanks again, Mark.

Mark Blyth

Cheers.

Paul Jay

And thank you for joining us on theAnalysis.news. Don’t forget the donate button and subscribe and share, and we’ll see you again soon.

Stephen Donzinger interview should have Mark hanging his head in shame, the corruption he defends as rule of law.

Speak of timely news, just got off phone with client at TSMC. Trump, and now Biden is backing the order, ordered Taiwan’s TMSC to build a semi-conductor plant in USA to “steal” their 3nm chip technology as condition for weapon sales to Taiwan. TMSC is dragging it’s heals to complete the plant because Taiwan Government knows once it goes on-line, there is one less reason for USA to protect Taiwan’s current batch of oligarchs. That’s intellectual property theft of the first class.

Is Mark aware of USA seizure of Citco? USA seizure of Iran, Iraq, Libya reserves, theft of native Americans lands happening this year? Use of US military to steal resources around the world? Threats against any company investing in NorthStream2? Further, USA used 5 Eyes spying to steal intellectual property from Japan, EU nations (reported in Wikileak’s Stratfor files)? The man spends too much time in DNC controlled circles.

He’s forgotten the UK socialist state, murdered dead by USA cooperating with UK oligarchy, that allowed his bones to make it through graduate school, otherwise he’d be just a smart guy pitching lines in run down pub in Glasgow.