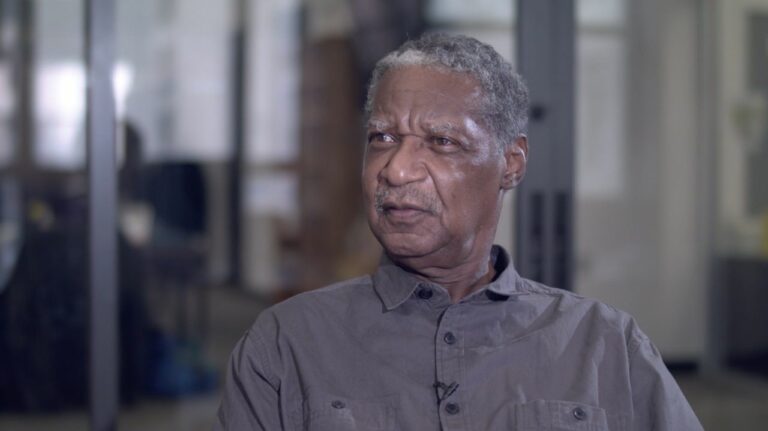

This is an episode of Reality Asserts Itself, produced September 25, 2013. In part two of Reality Asserts Itself, Paul Jay and Rania Masri discuss the charge that opposing foreign intervention is support for Assad; the idea that Assad is “anti-imperialist”; and the role of violence in fighting dictatorship.

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay. And we’re continuing our series of interviews with Rania Masri, who now joins us in our studio.

Rania’s been an outspoken critic of the Obama administration’s recent push for military intervention in Syria. She’s an antiwar and human rights activist, a writer, and a professor of environmental science at the University of Balamand in Lebanon. She’s also director of the Southern Peace Research and Education Center at the Institute for Southern Studies in North Carolina. And you can find out more about her biography under our video player, where all the various books she published in are mentioned and such. But here she is.

Thanks for joining us again.

RANIA MASRI, HUMAN RIGHTS ACTIVIST, ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENTIST: A pleasure. Thanks.

JAY: So I should have done this in part one, where we’re a little more biographical. So I’m going to pick it up here, and then we’re going to get into some of the current politics.

You are a professor of environmental studies. You are an expert on climate change. You are all into the climate change debate. And at the same time, you are very active on antiwar issues and such and that. But if I got it right, your degree had something to do with studying trees. You were going to be, like, a–you have a forest degree. What were you going to be? Out there like a forest ranger?

MASRI: Well, I specifically–my dissertation was actually entitled morphological differences macro public–God. I forget the full title. Basically what I studied was clonal propagation of loblolly pine trees.

JAY: Say again?

MASRI: Exactly. I haven’t touched it. I studied it–.

JAY: How pine trees reproduce.

MASRI: Clonally. How can we clone them. And I studied the different morphological traits of different clonal propagation techniques of loblolly pine trees.

JAY: So why did you do this?

MASRI: Why did I study forestry? I know. The stupidity of youth.

JAY: What was the logic? You were going to grow up and be a biologist?

MASRI: No. The logic was–at 16 I went to a Jeremy Rifkin talk, and I heard him speak about environmental catastrophes, and I walked away in tears, feeling that I could no longer pursue my dream of studying comparative literature, because that would be such a peak of selfishness that I had to become an environmental scientist and save the world. Again, this is 16-year-old melodrama. What I failed to do is examine that with age. But nevertheless, I did my bachelor’s, my master’s. And, of course, I had to do a doctorate. And dissertations are all based upon detail.

JAY: That’s a lot of years to be studying trees.

MASRI: No, I only studied trees for five years.

JAY: Oh, that was just the doctorate.

MASRI: That was just the doctorate. The previous five years were general environmental studies and environmental [crosstalk]

JAY: Okay. So you graduate. You are now a doctor of trees. And you drop it. You drop it.

MASRI: I join the Institute for Southern Studies, and I do southern organizing, and I study relationships between peace and justice issues in the South–and I mean south of the Mason-Dixon line in the United States–and how they connect with militarization and U.S. foreign policy.

JAY: But you teach climate change.

MASRI: Well, now, you know, since 2005 I’ve been teaching environmental science in Lebanon, and I teach a range of classes, from undergraduate to graduate courses, one of which is climate change, where we study science and policy and impacts.

JAY: Okay. Well, if we can, if we have enough time, we’re going to do a segment about climate change, but for now we’re going to kind of carry on with our track of the Middle East.

As we learned earlier, the first Iraq war really galvanizes you, and you become an activist and antiwar activist and such. Now we’re going to kind of jump to more current period, although including the Iraq War, but Syria.

One of the critiques of you has been that you spend so much emphasis and focus opposing foreign intervention that you wind up–this is not my words–but a little bit of an apologist, a little bit soft on either Saddam Hussein in Iraq or Assad in Syria, and that you’re not focusing enough on the aspirations of either the Iraqi people or the Syrian people to get rid of their dictators. And let me say for anyone–I mean, anyone who watches knows what I think about these things. This is not some way to say that U.S. intervention in Syria or Iraq would have been a good thing, and obviously it was a disaster in Iraq, and we’ve said it on The Real News 4,000 times. That being said, we’ve always also focused on what was wrong with these regimes. And as I’m saying, you’ve been kind of criticized as not doing that. Is that a fair criticism?

MASRI: It is fair if you look at the bulk of my actions. And yes, the bulk of my activities have gone into shifting U.S. foreign policy and making Americans much more aware of the impacts of U.S. foreign policy, which to me is a logical action for me to do, given that I was based in the United States. So that becomes logical.

What upset me the most was this kind of binary assumption that people gave: if I am opposed to economic sanctions on Iraq and I’m opposed to U.S. bombing campaigns on Iraq, therefore I must be a lover of Saddam Hussein. Same thing applies now: if I am opposed to U.S. bombing campaign on Syria, therefore I must be a supporter of the Assad regime. And both are ridiculously false. You know. I’ve never been a supporter of the Saddam Hussein regime, never been a supporter of the Assad regime. But it’s this binary presentation that I find to be most problematic in discussing issues. You know.

I stand very much against acts of economic violence and acts of military violence, completely. So in this case, economic sanctions against Iraq were themselves truly a weapon of mass destruction, were themselves horrendous in their impact on people’s lives. And bombing campaigns are not an option. They’re not a peace mechanism. So in those aspects, yes, my loudest actions were in opposition of those.

JAY: Now, you could say, in terms of this binary framing, you do get that from sections of the left in some very prominent people. I mean, Hugo Chávez while he was alive, currently Morales in Bolivia, they describe Assad as an anti-imperialist regime.

MASRI: Yeah. He’s not. The Assad regime is not an anti-imperialist regime. And I think to get that label, one has to work very hard both domestically and internationally, and the Assad regime is not. The Assad regime is a symbol of resistance, not a resistance itself, but a symbol of resistance, solely in its financial, military, and diplomatic support of Hezbollah in Lebanon. Beyond that, not all. Not at all. And I think we need to clarify that.

And there is no need to present the Assad regime in an angelic light as I have seen some people do. We do not need to do that. It’s not that I’m going to argue that we shouldn’t for credibility’s sake, but we shouldn’t at all. There’s–one, it’s wrong. The regime, both father and son, have committed crimes of atrocities, be it economic oppression, political oppression, participating in rendition, which Bashar al-Assad has done, not just his father. There are numerous crimes predating the uprising. You know. We can talk about 2011 forward, but I think what’s more important is 2011 backward, the crimes that the regime has committed, most definitely.

The Syrian people, as all people, deserve a different government, one that is democratic and representative.

JAY: And Assad was very happy to work with the Americans after 9/11. Anyone can talk to the Canadian Maher Arar, and he was only one of many people who suffered rendition to Syria and torture.

MASRI: Yeah. And I remember Hafez al-Assad, the father, and his participation in the Iraq War and the numerous crimes that the Hafez al-Assad regime did in Lebanon from ’77 onwards, be it against Palestinians or Lebanese or Syrians. So most definitely this is not an anti-imperialist regime. And I would urge people not to fall into that binary. The enemy of my enemy is not necessarily my friend. Just because the United States right now is looking at Bashar al-Assad as a foe, you know, not a friend, doesn’t necessarily immediately put him into the friend category. It doesn’t work that way, and we need to be more complicated about that.

But I also believe that in Syria we’re seeing hesitancy among people to actually engage in dialog. There’s become a knee-jerk reaction amongst activists across the political spectrum on this issue to immediately resort to name-calling, to immediately resort to objectification and binary presentations, and we should not do that. It becomes very, very problematic for us. And it’s problematic and unhealthy and divisive and not honest.

JAY: Well, you had a quote in an interview on our–you were with Chris Hedges, and you said something which kind of caught my attention. You said none of the armed players in the opposition in Syria–I think your word was that they’re all problematic.

MASRI: Yes.

JAY: You think that because you just think people shouldn’t pick up arms? Or you’ve done an analysis of who all these people are and they’re all problematic?

MASRI: Both, to be honest. One is when we look at the various sources out there, we see that with regards to the armed battalions or brigades or rebel forces, however language we want to use, the strongest of them, the most courageous of them, the most organized of them, regardless what percentage we give them, remain al-Qaeda forces in Syria. You know. If we’re going to talk about their organization, their military capability, and their rush to the battlefield, they remain that.

JAY: Now, are you sure of this? ‘Cause there’s a lot of debate about–I don’t think anyone’s debating that they are a very powerful fighting force, but there’s a lot of debate whether they are the fighting force or the majority fighting force.

MASRI: I’m not saying whether they are the majority or not, whether, as some representatives claim, that they’re 50 percent of the armed brigades, or whether, as Kerry claims, that they’re 15 percent. But from the various sources that I’ve read, they are definitely–.

JAY: Which Putin said Kerry was lying, actually used the–called him a liar.

MASRI: Yes. It could be. You know. I don’t know, and I can’t claim one or the either. But they are definitely a significant force in Syria.

JAY: But you do go to a point where you think–and I think you said this in our first interview–that any use of violence, any picking up of arms when it’s a domestic struggle is wrong. It’s okay if it’s necessitated by foreign intervention, but not domestically. But what if the regime–and many people are saying this is the case in Syria–and what if the regime makes any form of legal protest impossible?

MASRI: Well, we know for a fact the regime has committed atrocities. But when I look at it both strategically and ethically, I have issues with the use of violence, because I believe that the use of violence simply extends the use of violence. It encourages different layers of violence. If we have a military force that is significantly stronger, which is the Syrian army–they are the strongest military force in Syria–and I were to use weapons against them, then they would respond by using larger-scale weapons against me, and we continue with the cycle of violence, not getting anywhere closer to a negotiation. So from that sense, strategically it doesn’t make sense to me. Ethically, I also don’t believe it makes sense.

JAY: Well, let me just add one thing. The only reason that even worked in Syria is because you have foreign players willing to finance and arm. If it was just based on Syrian resources, the opposition wouldn’t have been able to form those groups.

MASRI: Well, then it would rely on the defections from the Syrian army.

JAY: Right. But there is one counterargument. You have another force outside arming the Syrian government. So it’s–then you get this imbalance. One side’s getting foreign support, and in theory the other side wouldn’t.

MASRI: Well, there will always be an imbalance. I mean, and one can argue: can the militia groups in Syria, all these different rebel brigades, ever be as militarily strong as the Syrian army? And that’s questionable, that’s controversial whether they can ever be. But the more weapons that they get, the more–the higher the level of weapons the Syrian army will use, and the cycle of violence continues and continues forward, and it will lead us to where we are right now in Syria, where there’s a destroyed country, you know, a third of the country displaced. Okay? So strategically it just doesn’t make sense to me. And, again, I’m not justifying the use of force committed by the Syrian government in any way. I just don’t think it’s a strategically wise move to use violence in response to that use of violence.

JAY: So, in other words–.

MASRI: And nor do I agree with it ethically, though.

JAY: So, in other words, mass protest. And if violence is used against a mass protest, you answer it with more mass protest.

MASRI: Again, to recognize that I am making the statement from a point of extraordinary privilege. And I recognize I am saying this not being on the ground in Syria but being in a place of comfort.

JAY: Well, to some extent it is what the Egyptians did.

MASRI: Yes, to some extent, yes.

JAY: You know, it–more or less the mass protests did not fight back with guns.

MASRI: Yeah. It’s what the civil rights movement did. Of course, I’m not comparing the level of violence that was used against the civil rights movement in the U.S. to the level of violence used against the protesters in Syria, but nevertheless we have all these different examples of nonviolent protest. And there is an ongoing nonviolent protest in Syria.

I believe very much that the main issue in Syria is a political problem. We have an oppressive lack of–you know, not a representative government in Syria. It’s a political problem. Therefore we need a political solution. And yes, it would take longer through nonviolence than it may through violence, but I believe it would actually save lives in the longer run, rather than what we’ve seen right now.

JAY: Political solution meaning that the opposition should negotiate with Assad.

MASRI: Yes.

JAY: Which most sections say they won’t do–not all. I mean, there are sections that do want to. They just want a ceasefire and stop the killing. But the more militant sections say they won’t negotiate with Assad.

MASRI: Exactly. And the Saudi- and Qatari-appointed external opposition very much feel opposed, of course, to negotiating with the Syrian government.

JAY: And most of those fighters, al-Qaeda type fighters, it’s presumed that most of their money’s coming from sections of the Saudi family and other of these various billionaires and rich supporters of al-Qaeda type forces.

MASRI: Primarily Bandar bin Sultan, most definitely.

JAY: Yeah. We’ve discussed before–to a large extent this has turned into a proxy war.

MASRI: Yes.

JAY: And we see that, you know, this negotiation on the chemical weapons was not a negotiation between the United States and Syria, although why United States has to be the player on the other side is another question. But it’s a negotiation between the United States and Russia. And to a large extent this is becoming a multifaceted proxy war, with the Saudi-Iranian contention and the American-Iranian contention and American-Russian contention. But the two big behemoths in the room are the Americans and the Russians. I mean, do you think there should be pressure that the two of them need to do–create the situation for a political situation?

MASRI: I would love that. I would love for both of those parties to put pressure on their allies, for the United States government to put pressure on the Saudis if they can, on the Qataris, on the Turks, on the others to actually halt the arms flow into Syria, for the Russians to do the same, to push all parties, primarily Syrians, of course, to the negotiating table.

What is most ironic about all this conflict is that the parties that have been negotiating are not Syrian. You know. The most important voice here, the Syrian people, the Syrians themselves has been left out of the negotiating table. And it continues to be left out of the negotiating table.

And I would argue that the Syrian National Council is not a representative of the Syrian population, that the people who claim to lead the Syrian National Council, they don’t have any legitimacy within Syria. They have legitimacy for the Saudis and the Qataris who have appointed them. And yet they are the ones being presented by the Americans and being taken into these negotiations, you know, when Syrians are present at all.

So, again, how do we get the Syrian voice? How do we empower the Syrian voice? That becomes, I think, the very difficult question.

JAY: Yeah, it’s a very, very difficult question.

And the underlying problem, I would think, in terms of getting the Americans to want to hold such a conference, peace conference, and actually have that agenda is it doesn’t seem that’s what they want,–

MASRI: Yeah, it’s not what they want.

JAY: –and neither the Americans nor the Israelis. And, of course, what the Israelis want I don’t think governs U.S. policy, but it sure influences U.S. policy. And they both seem to just want endless civil war.

MASRI: Yes, completely. And what’s stunning is that John Kerry has said so. I mean he said so during the Friends of Syria conference months and months ago, I believe, earlier this year, where he said that the objective is, quote, to address the imbalance on the ground. He didn’t say the objective was democracy, transparency, human rights, regime change, any of that; he said to address the imbalance on the ground. And that’s been reasserted several times since. So to address the imbalance on the ground means we want to make sure that no one party becomes the military victory, i.e. that they continue to kill each other until we, the U.S., have decided that’s enough, and then we go in and do whatever we want.

JAY: Just a–it’s a bit of an aside, and we’ll kind of get into this maybe a little bit more in-depth, but we were talking before that it’s kind of interesting that Israel supported Obama, and AIPAC was very active, apparently, in lobbying for support for this resolution in Congress to allow Obama to bomb Syria if he wanted to. And it was actually very interesting to see the weakness of AIPAC on this issue. I don’t know if it’s the weakness of AIPAC or it was AIPAC and Israel’s heart not in it. I don’t know.

MASRI: They failed to get one member of Congress to change his or her vote. Not one changed his vote. And I believe actually that one or two changed their vote from being yes in support of the bombing to actually becoming undecided. So it actually worked against them.

And if we notice after AIPAC flooded Congress, we had the declaration by Obama that he won’t put it to vote. And he won’t put it to vote, because he would have lost. He would have lost both the Senate and the House unquestionably. And that would have just been too much of an embarrassment.

JAY: Do you think–and, you know, Obama’s the focus of a lot of the critique on all this, and so it should be in the sense of Obama representing the American system here. But do you think Putin’s kind of getting off the hook here? I mean, he’s now the peacemaker, and he offered up this deal. I mean, if Obama hadn’t been arming–I’m sorry–if Putin hadn’t been arming Assad all this time, there might have been political negotiations a lot earlier. But as long as this carries on, why should Assad negotiate?

MASRI: Well, I’m not sure that there would have been political negotiations earlier, actually. I’m not sure about that.

Now, there’s one school that argues that the Assad regime doesn’t want political negotiations, that they haven’t been sincere about that. But there’s another school that says, well, let’s take him at face value. He’s been claiming he wants political negotiations, and the ones that have been openly saying they don’t want to negotiate (and they have these very difficult preconditions) have been the armed opposition brigades and the external opposition.

JAY: Well, it was that way, but now he calls the whole opposition al-Qaeda and he says there’s no one to negotiate with. I mean, he’s kind of dropped this idea that he was open to negotiations, maybe ’cause he’d gotten enough arms and the actual battle had shifted to somewhat in his favor, the momentum. All the recent statements I’ve seen from Assad is the opposition’s all al-Qaeda forces and there’s nothing to negotiate.

MASRI: And the statements coming from the opposition have reasserted that. You know. So I still argue that the Assad regime claims to want to negotiate. Whether or not they do is up for question, okay, versus the external opposition continues to openly state even recently–.

JAY: I’m just saying I don’t think Assad ever wanted to. But if the Russians and the Iranians (we shouldn’t forget about them) hadn’t been arming him and keeping him so relatively strong, he would have had to.

MASRI: Yeah. Well, I don’t know, actually, if the level of weapons that the Russians have given him in the past two years have been enough to shift the battlefield. Maybe they had already given him enough weapons previously that he already had enough of a military capability already to be able to weaken [crosstalk]

JAY: Well, I think the Russians are kind of playing the same game–give everybody just enough arms to keep killing each other–’cause right now it’s not so bad for the Russians. Assad is essentially completely dependent on them.

MASRI: Yeah. I don’t think that we need to trust the Russians. They remain an imperial force. They remain, you know, a government that has committed its own share of crimes of atrocity. In no way do I look at the Russians as a comrade that I will trust blindly. No, in no way. And I don’t believe that anyone actually has the interest of the Syrian people at heart.

JAY: Okay. So we’re going to continue this in the next segment of our discussion. Please join us for the continuation of our series with Rania Masri on Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network.

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter

“Rania Masri is a human rights advocate and environmental scientist. Born in Lebanon, she is the coordinator of the Iraq Action Coalition and served as the Arab Women’s Solidarity Association’s representative to the United Nations. She’s the director of the Southern Peace Research and Education Center at the Institute for Southern Studies in Durham, North Carolina. A dynamic speaker, she’s in great demand all over the country. She’s also a producer of a new documentary entitled About Baghdad.“