This is an episode of Reality Asserts Itself, produced September 25, 2013. Paul Jay talks to peace activist and environmentalist Rania Masri about her journey – from Bahrain to North Carolina, from scientist to global activist.

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay in Baltimore. And welcome to Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News.

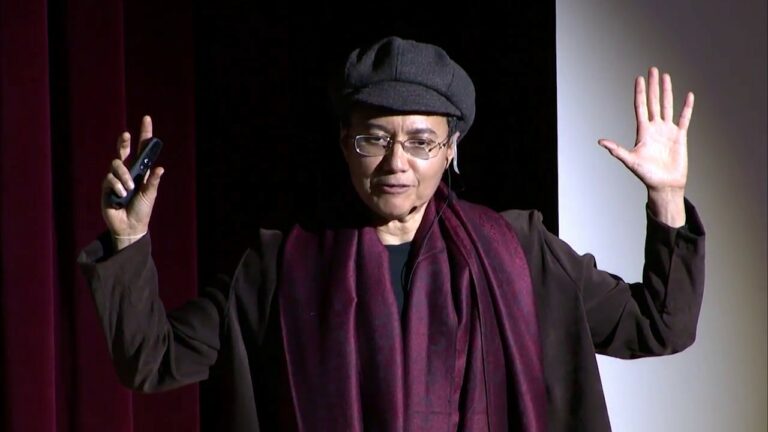

Now joining us for a series of interviews is Rania Masri. She’s an outspoken critic of the Obama administration’s recent push for military intervention in Syria. She’s an antiwar and human rights activist, a writer, a professor of environmental science at the University of Balamand in Lebanon. She also has directed the Southern Peace Research and Education Center at the Institute for Southern Studies in North Carolina. She was an outspoken critic of the Iraq invasion and the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories. She’s been published in several collections and different books, including Iraq: Its History, People, and Politics, Iraq Under Siege, and The Struggle for Palestine. Thanks very much for joining us,

RANIA MASRI, HUMAN RIGHTS ACTIVIST, ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENTIST: A pleasure. Thank you.

JAY: I should add that she’s here in the U.S. for a little bit, and she’ll be going back to Lebanon just a matter of a few days. We insisted that she come here before she go, before she went. So the way Reality Asserts Itself usually begins–and we are going to do it now–we start with a bit of biographical information about our Guest, more about why they think what they think rather than what they think, formative experiences in their life, and then we get into issues more current.

So start off from the that. You were born in Beirut.

MASRI: Yes.

JAY: Is that correct? But you actually grew up in Bahrain.

MASRI: Yes, that’s correct.

JAY: So–until you were 14. So in terms of growing up in Bahrain, give us a sense of, you know, how that helped to form your view of the world, especially politically.

MASRI: I’m not sure that particularly those 14 years helped form my view of the world as much as growing up already as an outsider. Although I was an Arab growing up in an Arab country, it was very clear to me by my neighborhood and by my own family that I was not Bahraini, I was not from the Gulf, and we did not belong there.

JAY: And why was your family there?

MASRI: Typical Lebanese family, there for work, you know, so with the idea, of course, when my father married my mother,that they would leave Lebanon just for five years. They left in ’67 and haven’t been back since. So five years tends to extend, as is typical with immigrant families.

JAY: Now, how aware were you of the politics of Bahrain? A monarchy, a majority Shia population that felt not represented by the monarchy, I guess nothing like the level of struggle that we’ve seen recently, but certainly some signs of it.

MASRI: I mean, as a child, I wasn’t that aware of that. But what I was aware was the prevalence of the Bahraini intelligence. And they were everywhere. I mean, every beggar literally was an intelligence agent. And so we’d typically laugh when we passed a beggar who smiled, you know, who had Chanel perfume or poison perfume on. You know, you could see, wait, hold on, you’re not even doing a good job of pretending to be poor. Literally every beggar was intelligence. We had weekly visits from intelligence agents who would just come to our home regularly, pretending that they weren’t agents, pretending that they we didn’t know that they weren’t agents. It was all this deception back and forth. I remembered numerous times being face to face with intelligence agents doing all kinds of–now what I consider to be quite ludicrous. I mean, it wasn’t even covert. It was open. And it wasn’t because we were any particular family. I mean, my parents were political in Lebanon, but they didn’t engage in any kind of political activity in Bahrain. But nevertheless we were under surveillance, as I think a lot of people in Bahrain were under surveillance. So I was aware of that very consciously.

JAY: How aware were you of your father’s politics? And kind of give us–now, we talked a little bit before hand, and it’s kind of complicated, actually. But give us a sense of the mileu that you grew up with, ’cause he was a political being, your father is.

MASRI: Well, I mean, my father, you know, became political. He joined the Syrian National Social Party in Lebanon when he was very young. My mother also joined young. Both sides of my family were members of the party. They were no longer active when they left Lebanon, but I grew up with the idea of the ideology of the party akin to how a Christian grows up with Jesus Christ in the family. You know, that–it was the upright bringing.

JAY: So it’s strong.

MASRI: It was strong, very definitely. This was the ideology that we were raised with as a family.

JAY: And I’m sure 99.9 percent of our audience has no idea what that ideology was.

MASRI: Yeah, what I just said. Yeah.

JAY: Well, they kind of, I think, understood that, but they don’t know what the Syrian National Party, what it believes. So give us a quick take.

MASRI: Three basic aspects. They believe very much in separation of religion from government, very much in a private religious adherence. And my family took that to an extreme, which is, if you were to walk into our home, you would have no idea what faiths my parents believed in. If you were to ask me, I wouldn’t tell you. I was raised that that was a very personal question, and you would not be of get an answer out of it.

JAY: You mean whether they were Christian or Muslim

MASRI: A Muslim or Jewish or Druze or whatever or atheist. It was irrelevant. I was raised that religion is the way that you treat people, and everything else is a personal decision between oneself and one’s God and however way ones choose to worship. So that was very, very intrinsic to our upbringing. That’s one caveat of, one basic tenet of the political party. The other tenet is that they believe in something called natural Syria or greater Syria, which is that Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine, Iraq are actually one natural entity and they are one nation. And it goes on beyond there.

JAY: Including Palestine.

MASRI: Yes, most definitely including Palestine.

JAY: And so the Palestinians clearly don’t agree with this.

MASRI: Well, it depends, I mean, because it’s not saying that Palestine is a part of Lebanon. It’s saying that they are all part of this one greater nation that is called Syria. Okay? And so the way that I was raised, then, is that the Palestinian is not my cousin; the Palestinian is my brother, in the same way that a Lebanese is, that a Syrian is, very much. So I never looked to a Palestinian as a foreigner. And that then impacted the way that I approach the political system.

JAY: And the idea here is that the Syrian and Lebanese borders in the region are all kind of artificial made by outsiders.

MASRI: Exactly, exactly, made by Sykes-Picot agreement. They don’t have natural boundaries. They don’t have historical differentiation. So, consequently, we don’t subscribe to them as being separate nations. They are separate countries, but not separate nations.

And then the third tenet of the ideology is that economically they believe in something called profit-sharing. So the worker does not own the company, the factory, per se, but the worker gets a salary at a percentage of the profits. And here my father, you know, actually lived it. This is one thing that I’m extraordinarily proud of is not only did he believe in a particular ideology, but he practiced it, he practiced it in the way that we were taught religion is private, and he practiced it in his own company that he actually gave employees a fair salary and–.

JAY: And you told me earlier that over the time in Bahrain he developed a furniture business.

MASRI: Yes.

JAY: A retail business? Or manufacturing?

MASRI: Retail. And Bahrain, as all GCC countries, if you’re not from the GCC, you don’t have the right to own majority shares in the company, you don’t have the right to own property. You can only own a car. So my father had 49 percent of the company that he built. But he made sure that the employees got not only a fair wage, but that they got a percentage of the profits that they helped contribute.

JAY: But given the rich history of the region, where you had very strong socialist parties and Communist parties who were for public ownership, this tenet of profit-sharing can also be seen as a way to protect private ownership, as opposed to this.

MASRI: Possibly. But to be fair, the founder of the party, [anton@’saIdi] didn’t really discuss economics that much. He spent a lot more time during his short life examining more what comprises a nation and how we define religion, and really stressing the importance of being a secular nation, of having a civil society and not a religious society. Those were his main issues of emphasis. Had he lived longer, we may have seen the economic aspect to be more complex and to have it seen expanded. But that wasn’t the case.

JAY: But when you grew up, the Assad regime, the Ba’ath party, were they considered good things, allies, or enemies?

MASRI: The word enemies is a very particular word. And the way that I was raised is that term is used only for the Israelis, and it’s only been that the apartheid occupying state of Israel is the enemy. All the others are not necessarily allies, but we have disagreements with, you know, we may have political differentiation with. But the word enemy is a very particular word. So myself, I remain–I only consider Israel itself to be an enemy state. It is a failed–not a failed entity; it is a forced entity, a foreign entity on our land occupying our people, continuing with apartheid. So the term enemy would only use to that. Now, one could argue there are political differences between various different political parties, and they may serve–they may meet on particular issues and not. You know. But, again, enemy I would just limited to Israel.

JAY: Well, certainly, today in Syria there are a lot of people that will use the word enemy when they’re talking about the Assad regime. But the party, at least,

the Syrian Nationalist Party, they’re actually working in the Assad regime right now. There is a minister from that party in the Assad regime. So, I mean, the fact that the struggle in Syria has so divided society–and we talked about it in an earlier interview. You know, you have proxy war, you have civil war, you have revolution. But generally speaking, the opposition considers somebody working in the government on the other side of the barricade and thus an enemy.

MASRI: True. I mean, again, I would prefer not to use that, because I think enemy then would justify the use of violence, per se. But yes, the opposition would consider the Syrian National Social Party to be an opposing force and not necessarily to be an ally. That is a fair judgment, yes.

Now, I have to say, for full disclosure, that I myself, I’m not a member of the Syrian National Socialist Party. Nor can I claim to speak in their name.

JAY: Right. So we’re dealing with sort of the first 14 years you are in Bahrain. You’re not all that political. You’re a teenager.

MASRI: Yeah. Ironically, I went to a DOD school, though. I went to a private school run by the U.S. Department of Defense. So we had an American flag. We had Girl Scouts. We had an American military base right next door. You know, a typical DOD school. That was my upbringing.

JAY: Well, when does–you describe the only state that you would call an enemy state is the Israeli state. Is this something you are aware of?

MASRI: All my life.

JAY: Well, then, you’re going to a school with a flag of the country that is making this state more or less possible.

MASRI: Yes, and that was very clear also that, you know, I am going to an American school that was at that time the private school that a lot of immigrants would send their children to. So it was just a natural choice by my family. I was very aware that the United States, yes, is the main supporter of Israel, and Israel is the enemy, and so there was that. Most definitely there was that growing up.

But what we noticed also–what I noticed very much is that I was a product of globalization before globalization was a term. And, again, nothing about this is unique or exceptional, you know, growing up in Bahrain, growing up with American music, American culture, an American school, and American literature. So a part of me was American before I even moved to the states. We find that with globalization to be very typical.

JAY: Yeah. I was going to ask that, ’cause I have a game that I play with, you know, trying to understand–try to guess somebody’s history listening to their accent and their English, and I probably would’ve guessed you were born in the States, but that’s because you’re going to this school.

MASRI: I went to that school, yeah.

JAY: Part of the luxury of this Reality Asserts Itself is I kind of jump around a little bit. And I’m going to do a bit of a jump. When you say Israel is the only enemy state, so the Saudis, the Saudi regime, for example, that’s fueling the civil war in Syria, that is, you know, more or less, you know, barbarically treats a lot of people. They invaded your Bahrain. So you don’t consider the Saudi state–you can’t use the word enemy?

MASRI: As the state? No, because then I’m considering the country to be an enemy. In terms of the Saudi government, they’re most definitely not a friend, they’re most definitely not an ally in any way, shape, or form. They are most definitely an opposition force. But, again, the term enemy I would refer not only to the government but to the entire country.

JAY: Because doesn’t that diminish the role of class in your assessment of all of this? I mean, Israel–unless you think the Israelis are some demonic force that–you know, Israeli exceptionalism, they’re the only enemy on the planet, then they’re part of the system.

MASRI: Yes, they’re most definitely part of the system.

JAY: And that system includes the Saudi royal family and the Qatari royal family and the Bahraini and on and on and on.

MASRI: And numerous other royal families.

JAY: And, yeah, the Israelis have committed some specific war crimes and the occupation is kind of at a different scale, you could say, than maybe what some of the other countries are doing, but it’s all part of the same same jigsaw puzzle.

MASRI: It is, it is. And in many ways what the Israelis are doing is nothing new. Colonialism, ethnic cleansing, genocide is nothing new. You know. It’s for a long time I felt this. And I believe many of us from my region do feel very strong kinship with First Nation communities in the United States and throughout the Americas because they have suffered what we are suffering from right now. So there’s nothing new about what the Israelis are doing. But the fact is it’s ongoing. It’s not a past tense. It’s ongoing. And the difference between them and any other regime is I would differentiate between the state, which is an occupying apartheid state, most definitely, and the Saudi regime and the Qatari regime that are enforcing numerous kinds of oppression. And in Lebanon we have seen it, most definitely.

JAY: Also kind of concocted states, though.

MASRI: Yes. But then one can argue a lot of states are concocted.

JAY: A lot of states are concocted.

MASRI: Yes. In Saudi Arabia, because exceptional in that you have an entire country named after a family. You know?

JAY: And a family–the whole regime’s kind of brokered by oil companies who kind of marry the Wahhab tribe and the Saud family and create this whole–. And the Saudis have committed a lot of crimes. None of this is to let the Israelis off the hook, but the Saudis have committed many crimes.

MASRI: Nobody has a monopoly on war crimes, unfortunately.

JAY: Yeah. Okay. So we get to the age of 14. You’re political enough, first of all. You’re growing up in this milieu of the Syrian Nationalist Party. And if this is like religion at home, then this is a big deal.

MASRI: It’s a big deal. It’s very present, yeah.

JAY: And so part of that ideology is opposition to the Israeli occupation, and not just the ’67 occupation. I assume this is opposed that there shouldn’t have been a state of Israel.

MASRI: Most definitely.

JAY: A Jewish state of Israel.

MASRI: Most definitely.

JAY: So that much is clear. How much is that at the forefront of who you are? Like, are you such a political being that this is kind of on your mind? Or it’s just sort of in the background of the ideology?

MASRI: It’s always present. There’s–I can’t really separate the personal and political. It’s always present.

JAY: As a teenager.

MASRI: I don’t remember a time when I was able to separate them.

JAY: So did you get into fights at this American school? Are you arguing with people?

MASRI: No, because it wasn’t an issue. At that age it wasn’t an issue. I mean, the main issue, I remember, at that age was what religion do I have, what religion do I subscribe to. And for me, being a lover of literature, I looked at the Bible and the Quran as two literary documents. I was compelled to see which one has a better story. You know. And I didn’t fall in love with either, which was perfectly fine in my family. You know. So the main conflict I had as a child was being asked to identify with one or the either, and I couldn’t and I wouldn’t, and I wouldn’t even answer the question. But it really wasn’t a conflict.

JAY: So what is the attitude, then, other than Israel? I mean, let me put it this way. Your parents couldn’t have been that opposed to the U.S. if they’re sending their kid to a U.S.-run school.

MASRI: Yeah. But I think we all have these hypocrisies and these contradictions in our way of life. I mean, we moved to the U.S. in ’86, and we moved to the U.S. for a reason a lot of the immigrants moved to the U.S.: education. You know. It was a very good place and it remains a very good place to go to school. So we moved. I mean, this black-and-white division doesn’t really apply. And for me it only applies with regards to Israel. Everything else is gray.

JAY: So you get to–we’re going to pick up on that. We’re going to do a whole segment on Israel-Palestine. So we will dig into that more. But let’s move on. So you are 14 and moved to North Carolina. Why North Carolina?

MASRI: My brother wanted to go to North Carolina State University. That was the only reason.

JAY: And he got in, and everybody moves.

MASRI: Got in, and we moved to North Carolina. That was it.

JAY: And your father does what with his furniture business?

MASRI: My father commuted for a year between Bahrain and North Carolina, and then commuted for several years between D.C. and North Carolina, where he got employment, and then became self-employed and North Carolina, you know, where he has remained.

JAY: And, well, you’d already gone to a U.S.-run school, so it wasn’t as much culture shock as it might have been.

MASRI: It was.

JAY: It was.

MASRI: Educational, there was no difference. Academically there was no difference. Cultural was significant because I went from an environment where I was accepted–I was an other in Bahrain, but I was still accepted–to an environment where I was the only non-North Carolinian. And here I was a Lebanese at a time where Lebanese were known terrorist. And so I was, you know, being asked–.

JAY: Okay. What year are we in?

MASRI: Nineteen eighty-six.

So the common thing at the high school was, you know, you’re an Arab, you’re terrorist, you know, where is your guns. And this was before they there were school massacres. And the only way I could deal with this constant harassment was to tell them, yes, I do have guns, and if you upset me one more time, I will bring them. And I had never seen a gun in my life. And when I come from as close to a pacifist family as I can–. But then they left me alone. So at least I was free of harassment in high school.

JAY: Well, if you’d done that after 9/11, you probably would have been in Guantanamo or something with language like that.

So what is the next to big, you could say, marker in your life for when you really start? I mean, you’re really politically active now. You speak about things. What’s the sort of thing that galvanized you?

MASRI: Well, I mean, I was active during my college years on Palestinian issues as so many other Arabs are. But the defining point for me was freshman year when the Iraqi army went into Kuwait and I felt my life my life just stopped, because that became the all-encompassing issue, how to stop the war, how to, you know, protect people.

JAY: So we’re talking 2002, 2003.

MASRI: No, we’re talking 1990.

JAY: Oh, you’re talking about the first Gulf War.

MASRI: The first Gulf War in August 1990 when the Iraqi army went into Kuwait, that was the first big shock for me emotionally, politically. And then it became so much of my life a few years, actually, for, five years later, when I became more aware of the sanctions and when I read a report published by the United Nations that was saying approximately 5,000 children were dying every month in Iraq because of sanctions. And there weren’t that many people crying out. And I decided I had to put–you know, I mean, during that youth, the teenage years, you know, were the times of melodrama. You know. So it was either/or and there was not that much gray in my life. So I decided Iraq had to be my focus and it had to be my prime area of activism, because I felt that there were not enough people speaking out. And before I knew it, it took up 60 to 80 percent of my life.

JAY: So you go to this American-run school in Bahrain. Then you continue your high school university education in the United States. Normally people get Americanized. And, you know, as much as the Syrian National Party might have been your religion growing up in your family, there’s a religion here called Americanism, and most immigrants, it doesn’t take too long before they, you know, drink the American Kool-Aid, and generation after generation it gets even more. Did you get Americanized, and that you become such an activist opposed to U.S. foreign-policy? How do those things relate to each other?

MASRI: I think it depends what you mean by Americanized. In many way I think I was Americanized before I came to the States, because, you know, I grew up loving country music, I grew up loving English literature and being more proficient in the English language than I am with the Arabic language. So in many ways I had already drunk from the American cup before arriving. And it was in the U.S., actually, that I learned how to organize and I learned what it means to work with others, what it means to move from identity politics to issue politics. I learned that in the U.S. So I am extraordinarily grateful to North Carolina and to the South in general and to the United States for giving me hope in political activism, hope in social justice activism, introducing me to numerous socialist thoughts. That is the Americanize that I took. So I didn’t take this idea of an American dream with a white picket fence and two dogs.

JAY: Yeah, you’ve written somewhere that your guide for Americanism, if you will, was Howard Zinn.

MASRI: Howard Zinn, most definitely, most definitely, yes.

JAY: Which is sort of the progressive vision of American history.

MASRI: But he didn’t just guide me in terms of progressive vision of American history. He guided me in terms of a progressive vision of history in general and how we can look back and obtain hope rather than to look back and feel defeated and feel broken. And we have enough evidence on both sides. You know. I can look back and say, we’ve just had centuries of oppression, be it political, economic, environmental, and feel really broken. And many days I do. But I can also look back and say, but human struggle has–continues. And there’ve been pockets of hope and pockets of uprising. Even when they fail, the mere aspect that people can stand up and say something and try to change is in and of itself hopeful. And that’s the school that I get from Howard Zinn, that I’m extraordinarily grateful for him for that.

JAY: Okay. Great. So we’re going to continue our series of interviews with Rania. Please join us for the next segment of this series on Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network.

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter

“Rania Masri is a human rights advocate and environmental scientist. Born in Lebanon, she is the coordinator of the Iraq Action Coalition and served as the Arab Women’s Solidarity Association’s representative to the United Nations. She’s the director of the Southern Peace Research and Education Center at the Institute for Southern Studies in Durham, North Carolina. A dynamic speaker, she’s in great demand all over the country. She’s also a producer of a new documentary entitled About Baghdad.“