The post-World War II era was characterized by decolonization in Asia and Africa, with resistance movements leading to the unraveling of the British empire in colonies such as former British Kenya, where the Mau Mau launched a lengthy uprising between 1952-1960, as well as in former British India, with the dissolution of the British Raj and creation of an independent India and Pakistan in 1947. Journalist Tom Stevenson provides historical examples illustrating how the rise of American hegemony following the decline of Britain’s imperial power was bolstered by British foreign policy at every juncture.

Bellicose British Foreign Policy in Ukraine and Gaza – Tom Stevenson part 2/2

Talia Baroncelli

Hi, you’re watching theAnalysis.news, and I’m your host, Talia Baroncelli. I’ll shortly be joined by journalist Tom Stevenson to speak about how Britain supports U.S. hegemony.

If you’d like to support the work that we do, you can go to our website, theAnalysis.news. Hit the donate button at the top right corner of the screen, and make sure you get onto our mailing list; that way, you’re always up to date every time we publish new content. You can like and subscribe to this show on YouTube or on other podcast streaming services such as Spotify or Apple. See you in a bit with Tom Stevenson.

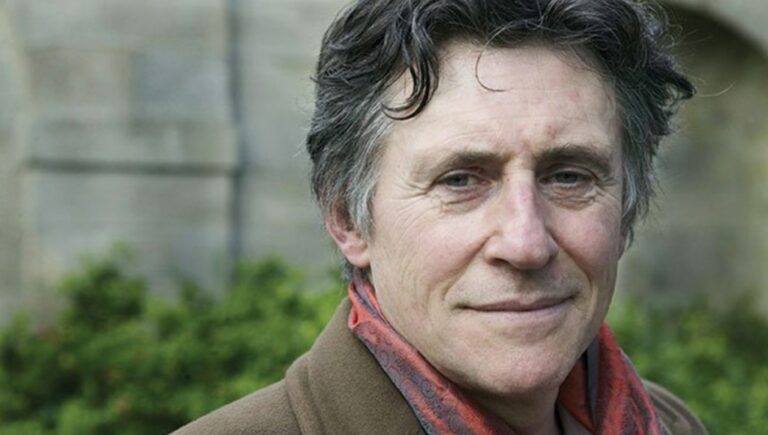

Joining me now is journalist Tom Stevenson. He is a foreign correspondence and contributor to the London Review of Books. He has reported from the Middle East and North Africa, and is the author of a collection of essays called Someone Else’s Empire: British Illusions, and American Hegemony. Thanks so much for joining me today, Tom.

Tom Stevenson

Thank you.

Talia Baroncelli

Your book, Someone Else’s Empire, does a really good job at illustrating how Britain became the eternal ally of the U.S., how it seeks to project imperial power, and prop up U.S. hegemony, but this wasn’t always the case. The U.K. or Britain, which should be distinguished from one another U.K., including Northern Ireland, whereas Britain just comprising England, Wales, and Scotland; how Britain was an empire. The British empire suffered many losses during the Second World War, during the First World War, and as a result of resistance from the people that it colonized, it began to implode from within. How would you describe this historical shift which led to Britain being the eternal ally of the U.S.?

Tom Stevenson

Well, I think that it has been clear, really, at least since the 1930s, that at present technological levels, industrial levels, the game of global power is one for subcontinental scale nations: the United States, China, Russia, and India. You needed that scale. I think even thinkers within the British empire, which, of course, remained in place until the early 1970s, formerly, were aware of this.

But nonetheless, in 1945, when the the absolute predominance of American power on the world stage really became completely undeniable and the general dynamics of a bipolar Cold War world became so apparent, British thinkers were obviously faced with a problem, which is they had a rump empire, shorn from 1947 of its most valuable possession in India. Therefore, what were they going to do and what was their approach going to be?

There was a brief period when Britain started to try the British empire, as it was then, started to play the role of what David McCourt once called the residual great power. But what, in fact, emerged over the next generation or so was something far more limited. The best description of it was really given by an American statesman, Dean Acheson, who, in 1962, made two comments about Britain’s role in the world.

The first one, which is perhaps the most famous, was that Britain had lost an empire and has still not found a role. The second was given in a private letter to another American ambassador, Robert Schaetzel, where Acheson argued that what the United States should try to do was get Britain to act as its left hand.

Now, that idea, in fact, became pretty much the governing principle for the British establishment over the next 40 or 50 years. At the time, Acheson’s comment was treated as a barb, and it caused something of a stir in Whitehall, which is the monarchy used for formal government in the United Kingdom. But nonetheless, it was taken up.

What happened was that Britain found itself bolting, especially its foreign policy, onto the United States as a way to augment its own power and retain some role in international affairs, justify its position on the U.S. Security Council, and so forth. I think that was the general purview.

Then, of course, that goes through a number of stages over the years, but that’s been pretty much the approach, I think, which is that Britain, rather than, say, retreating to being a small, relatively prosperous European country or attempting to be an independent power in its own right, found a new role, and it was more or less the role that Acheson privately described, which was to become a gratis mercenary in the projection of American power globally, or more politely, parts of what British pundits call the special relationship leadership playing a Greece to Rome role as wise advisor to upstart American power.

Talia Baroncelli

I wanted to ask you about a historical event which I think represents a shift in how the United States perceived the British empire, and that is the coup of democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh in Iran in 1953. It was British intelligence, the MI6, together with the CIA led by Kermit Roosevelt, who orchestrated this coup. There’s documentation that shows that this coup was a long time in the making. The Brits were opposed to Mosaddegh’s plans to nationalize its oil production. The Brits were actually in Iran for a long time, with the Anglo-Persian oil company taking as much oil and exploiting Iran’s resources for quite a long time, and Mosaddegh was opposed to this.

It was actually under President Harry Truman, the U.S. President, that there was opposition to the planned coup. I think Truman, at the time, was opposed to British imperialism and didn’t think that the British should be planning these sorts of coups in the Middle East. There was, of course, a shift, and I think President Eisenhower, once he came to power, tacitly gave the green light for this coup. I guess the initial opposition to this coup is apparent in Truman’s policies or approach.

That represents, at least in my view, how the United States wasn’t so keen on the British doing whatever they wanted to do in the region and in other parts of the world. Do you see this in the same way, or what’s your assessment of that particular moment in the ’50s?

Tom Stevenson

I think there’s a fairly strong argument for that. I would certainly agree that it is in the 1950s that one starts to see a turn in these matters. In the immediate post-war period, the United States was not yet fully committed to decolonization in the way that it would become in the 1960s. There is a passage there, and I think it would be certainly an interesting reading to treat Iran as a pivot in that history.

I think much more generally, in a more abstract way, the United States became, and I think still views itself fundamentally, as what John G. Ikenberry once called a non-imperial empire. It’s clear as to why that is and what the interests of that are. Therefore, there was ambivalence towards the European empires, especially the British empire, so long as it survived the 15 to 20 years after the Second World War, that it did survive, as to whether or not it was illegitimate and more to the point of how it should be dissolved, which was certainly most acute in the case of the Middle East. The hegemonic transition in the Middle East between British and American power, while it began earlier, even before the First World War, in the relationship between the United States and Saudi in the 1930s, was not fully completed until 1971 and has become an extremely important American interest that has governed so much of American policy to this day. Treating Iran as part of that moment is certainly, and the Mosaddegh coup as part of that is certainly very interesting. There’s no question.

Then, the other question that you raise, I think, is important, which is on the global intelligence networks. There’s a very prominent, very remarkable British scholar, Susan Strange, who once argued that the core of the relationship between Britain and the United States is the global financial networks that run between London and New York. In some respects, an even stronger core of the relationship is, in fact, through the intelligence agencies.

In 1945, the first major national security agreement made between the United States and the British empire at the time was what would become the Five Eyes Intelligence Sharing Agreement. That was very useful because there you have that interconnection between intelligence and foreign policy in that the United States really could get something useful from Britain and from the rump of the British Empire, which was a geographic scope for listening posts, for intelligence networks, for intelligence services, and the experiences that they had therein. As early as 1945, the war was not yet. It was just over, not even yet fully over. You already have in place what would become and is to this day an extremely important integration of intelligence services and networks, which we see in use, literally in Gaza right now, but also pretty much everywhere in the world, from Australia to Canada. That’s also an interesting overlap, this idea of forging together on the basis of questions of intelligence.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, given that you bring up that point of listening posts, I think that was really an important point to bring up Susan Strange because Britain has so many… because of its history as a colonial power, it has these various listening posts. It also has disputed territorial claims. I’m thinking of Diego García, for example, who has disputed a territorial claim with Mauritania, I believe. Or is it Mauritius?

Tom Stevenson

Mauritius.

Talia Baroncelli

Mauritius, excuse me. But they also have a specific post on Cyprus, and Cyprus is the point where the U.S. military is also using it as a base in order to… well, when we saw the U.S. dropping humanitarian aid to Gaza, I think it was using Cyprus as a specific launch off pad. There are several other listening posts and military posts around the world that Britain has.

My reading of your book, Someone Else’s Empire, is that Britain is actually more useful to the United States than the United States is to Britain. I don’t know if you would agree with that assessment, but I think there’s perhaps a lot behind that because, given the colonial history of Britain, there’s a lot of geographical breadth and assets that it has worldwide, which doesn’t necessarily mean that it has the military assets to support American hegemony. I think you were also writing that over the past few decades, Britain has actually decreased its funding of the military as a general percentage of GDP. Yes, it has increased funding towards certain vessels, such as the HMS Queen Elizabeth and Prince Wales. There’s been a lot of funding to the Navy, for example. But in terms of general military spending, it’s really not worth its salt, or it’s not very much. How would you characterize or assess that relationship? Would you say that perhaps Britain is more useful to the U.S. than the other way around?

Tom Stevenson

Yeah, I think there’s certainly a case for that. I think it’s something that you have to break down. The first thing is that one wouldn’t want to, I think, exaggerate the role that Britain plays in the global system. American power, given its sheer magnitude, could get along well enough without Britain. But the British establishment at the time, and to this day, has always faced the problem of how to make itself useful. I think it has found a number of ways to make itself useful to American power, as you said.

One was in that sense of geographic scope, having until recently, in some limited respects, still having the formal accoutrement of an empire, is simply having possession, legal possession of islands all over the place that were occasionally useful, either as bases, in some cases to be lent out on permit or leased to the United States, or just useful as staging posts, as listening posts, or whatever else.

Another, and I think a critical one has been in the provision of a veil of multilateralism, which we saw most prominently in Iraq. We’ve seen it on multiple other occasions as well, where the United States is able to say, “Look, we’re not just the biggest bully on the block doing as we please because we have the ability to do so, the strong do as they will and the weak do as they must. We’re acting as part of a coalition of free nations or to bring it up to the present as part of an alliance of democracies versus autocracies or whatever else.” Britain has very often played a marshalling role in that coalition of being part of the appearance of multilateralism and then also helping American power to drum up support from wherever it can.

Then you’ve got that, you’ve got that geographic scope, you’ve got elements of the intelligence network, and you’ve got multilateralism. Then also, although British military and economic power is in relative decline, in terminal decline in some respects, it’s also occasionally served as a 7% to 10% reinforcement to American capacities, which, while it isn’t decisive, it is not nothing. There’s been times when British involvement in American global designs has been a liability.

There’s no question that in the war in Iraq, for example, the British military intelligence establishment came in saying, “Well, look, we’ve got all this experience in counterinsurgency because of Northern Ireland and traditions going back horrific repressive wars in Malaysia, Kenya, and so on. We know what we’re doing, and we’ll be able to help in the post-war aftermath in Iraq and trying to pacify and rebuild the country.” In fact, the exact opposite was the truth. Every task that, sadly, the British Army was given, sadly, from the perspective of the generals who state their reputations on this, they just messed up completely and were able to offer nothing. All of that really became a total debacle, and it’s still considered a debacle by conservative forces within Britain today.

You know there are points on both sides of the picture. I think the general policy from Britain’s perspective has been very much to stand behind the Americans and nod. It has led, from the British perspective, in terrible directions. The post-911 wars alone, you’re talking about 4.5-5 million deaths, 40 million plus refugees, unspeakable crimes, numerous unspeakable crimes, for which in the American case, there was an organizing logic. I would consider it an immoral organizing logic, an immoralizing logic. With a global hegemon, we have to maintain hegemonic stability so the system doesn’t fall apart. It’s all in our interest and so on. Britain couldn’t make any of those arguments. The only argument ever was we have to stand with the Americans, stand behind the Americans and nod.

In that respect, I would certainly agree with your general assessment, which is that what Britain has got out of it has really been disgrace more than anything else.

Talia Baroncelli

I think the point that you bring up of how Britain provides that multilateral legitimacy in a way, giving the U.S. diplomatic legitimacy for its horrible policies, hegemonic policies around the world. In certain instances, it does seem like Britain has doubled down on those very belligerent positions. There are recent examples of that. If you look at the U.K.’s involvement in providing over £20 billion to Saudi Arabia for its intervention in Yemen, or even recently when the Houthis were attacking commercial vessels in the Red Sea, Rishi Sunak was saying that the U.K. needs to attack certain Houthi positions in Yemen, and doing so was in a way defending the global economy, even though there was no real legal basis for those extra-judicial attacks or extraterritorial attacks. It seems like whenever there’s a U.S. policy that’s just quite blatantly illegal or unlawful or in contravention of international norms, Britain doubles down on that, saying that it’s actually in the name of maintaining a rules-based international order. There’s a certain element of, I guess, changing the narrative and reinforcing it to meet the desires of the U.S. empire.

Tom Stevenson

Yes, absolutely. In the case of Yemen, I think everything you said is absolutely accurate in the case of the most recent naval operations against the Houthis. But it’s also more generally true of policy towards Yemen since 2014, if not before, which is that the current military action taken to do with the Houthis’ attempts to attack shipping through the Red Sea really has been based on a deliberate ignorance of the recent history of Yemen with regards to the civil war there and with regards, especially to what’s usually described as the Saudi attack or intervention, even, to put it in even more euphemistic terms, but ought to be described as an Anglo-American-sponsored Saudi attack on Yemen, which was for a long time the worst humanitarian crisis in the world, led to hundreds of thousands of civilian deaths, and has been just a terrible, really ought to have been a terrible stain on the consciences of everybody involved, and yet it hasn’t been. The reason it hasn’t been is that it’s taken place in relative silence. We’ve been talking about, as you correctly said, the idea of Britain and the U.S. taking military action to uphold international law, protect global shipping, and so on, as though there had been no war in Yemen, which is really only still simmering just underneath the surface, in which those two powers were very, very prominently involved. Very prominently involved in a way that was just straightforwardly illegal and extremely damaging.

I think it’s this effected ignorance or a deliberate incuriosity about the question which has really led to this policy, and really without any recognition or reflection on any of that. That’s amazing. You can have what became a really global news story alongside Gaza in which military action is taken by the U.S. and the U.K. without any reckoning of the truly criminal policies that had led up to it in the first place. Not only were they, I would argue, criminal, but they also failed in the sense that the stated goal was really to erode the power of the Houthis, which are pretty much the de facto government of most of Yemen, and completely failed to do that, but did succeed in killing very large numbers of people. That’s a really interesting dynamic of that as well.

Talia Baroncelli

We obviously can’t speak about, disastrous British expeditions into the Middle East without speaking about the war in Iraq and Afghanistan. A lot of your book also speaks about this lack of reflection on the part of the defense and military elite in the U.K., looking back on British track record in Iraq.

There have been numerous reports, such as a report that was conducted by Lieutenant General Chris Brown in 2009 called Operations Telic Lessons Compendium. I think one of the interesting things about this report, it did show that British military assets were really not up to snuff. British tanks couldn’t be relied upon to go further than 95 kilometers away from Kuwait. It doesn’t seem like there’s been much soul searching or reflection on the British military presence in Iraq. It was obviously a complete disaster. The Brits stylized themselves as being counterinsurgency experts due to their deployment or their experience in Northern Ireland. They were responsible for quite a few civilian deaths, such as Bloody Sunday in Derry in Northern Ireland. And because the 3rd Battalion, of the Parachute Regiment had been involved in Northern Ireland and was then deployed to Iraq, they thought that they had the necessary counterinsurgency expertise to do a good job in Iraq. Of course, they didn’t know the historical particularities in Iraq. Just as you said, they didn’t or they don’t know those cultural differences or particularities in Yemen. And so the same thing was happening in Iraq, and they arguably exacerbated the situation there, wrought all sorts of violence on the population, and then had to be escorted out of Basrah in an embarrassing way, just leaving so much destruction behind and having to be escorted out of there.

The British presence in Iraq was a clear disaster. There’s been some reflection on their expeditions in Afghanistan. Mike Martin, for example, has written a book called An Intimate War, in which he was questioning the strategies of the British presence in Helmand. But in Iraq, it’s been a complete disaster, and it doesn’t seem like there’s been much reflection on the part of the British military elite when it comes to what they did in Iraq.

Tom Stevenson

Sure, absolutely. That applies with equal force to Afghanistan as well. Yes, I mean, as we touched on earlier, I think that both in Afghanistan and especially in Iraq, Britain still had this idea of itself as being the counterinsurgency specialist, which would be able to really help. The caricature was a grunt to American power. They may have all the soldiers, all the money, and they may be leading the dance, but we’re the real specialists who will be able to provide nuance or some elegant insights and abilities here and there. That mythos was just completely fractured because every single job, unfortunately, that the British Armed Forces were given, both in Basrah and in Afghanistan, principally in Helmand, they made a complete hash off in every respect. So much so that the British Army presence in Basrah ended up having to be smuggled out of the city at night at the last minute because they’d completely lost control of the situation, having nonetheless employed a great deal of exemplary violence, which we’re still uncovering the details of to this day. They had to be completely bailed out by local Iraqi forces and by the United States.

Then, in Afghanistan, what was presented as, ahead of its time counterinsurgency tactics that would really show how things can be done with a light foot and so on, turned out being literally the use of death squads, to the extent that there is now an inquiry which is unfortunately subject to extremely harsh control in terms of press reporting into British Special Forces units that were basically just conducting night raids in Helmand and in Afghanistan, and executing prisoners in front of their families. There have been at least 80 documented cases of this. We still certainly don’t know the full picture. It was an absolute disgrace that we are still learning about to this day.

In both cases, that image was not only mythical, but it was the opposite of the truth. British forces ended up being understaffed, incompetent, and where they were able to do anything, it usually ended up deteriorating into just the exercise of war crimes. That is the actual record.

Talia Baroncelli

Could you speak about how it hasn’t really been any specific party that has been behind this push to constantly support U.S. hegemony? I mean, it’s not necessarily the Torys. Of course, the Torys are extremely belligerent. If you see the Defense Secretary, Grant Shapps, he had this video talking about the era of the peace dividend is over and how Britain needed to be trained and ready for various forays abroad, and they had to be prepared for any war scenario in a way. But this is not just coming from conservative rhetoric.

You also speak about, I think it was Ernest Bevin in 1927, the first post-World War I, Foreign Secretary who was a Labor Secretary. Perhaps he coined this, I don’t want to say belligerence, but this idea that the empire could not be neglected and that there needed to be this outlook globally. It’s not just Tory or the Conservatives who have been pushing for this alignment with U.S. hegemony, but it’s also been the Labor government. Iraq was under Tony Blair, for example. If you look at the current leadership, Keir Starmer, he doesn’t seem to undermine Tory’s positions on Gaza or Yemen at all.

Tom Stevenson

I’d say exactly right. In fact, the problem goes even beyond that because it’s both true, as you say, that the Labor Party, which is the nominally Center Left Party in Britain, has, if anything, a worse record than the conservative Tory Party, in terms of foreign policy on the issues, and especially in the use of force internationally on the issues that we’ve been describing.

It also represents something, I think, in the national culture, which is that for the most part, and this is a structural difference with the United States, foreign policy in Britain is primarily treated as a technocratic idiosyncrasy. That is, it is something that is to be left to specialized ideology professionals and not a subject of national politics. There’s almost a tacit agreement that on most foreign policy questions, they’re left at the channel. Politics stops there. It’s an internal matter.

Now, Britain is an island. Part of that is the natural provincialism that goes along with that. In some respect, that’s understandable. But in a deeper sense, given that there is enormous emphasis put on Britain’s role in the world, this political fact has real ramifications. Across the party political spectrum, with few very small, somewhat marginal exceptions, there is consensus on what I would describe as strategic Atlanticism, the idea that Britain’s role in the world is to stand behind the Americans and nod. So much so that it’s very rarely questioned. This has curious distorting effects.

On most foreign policy questions of the kind we’re looking at, from the Iraq war to Britain’s current policies on Gaza and everything in between, public opinion, to the extent people are asked, tends to be pretty much the opposite of government policy, and that is not reflected in any political party. In fact, it rarely ever bubbles to the surface at all, and that’s a remarkable fact.

The current Labor government, for example, has a position on Israel’s attack on Gaza that is really indistinguishable from the ruling conservative party position, as do smaller parties like the Liberal Democrats, the Scottish National Party, even the Greens, and so on. There’s almost nothing. In fact, this observation was remarked recently by one of the foremost thinkers within the British Defense Intelligencia from a think tank called RUSI, who basically said there was a vote on Gaza, which turned out turned into a debacle. It turned into a debacle basically because of internal political rambling, not for any position of principle. David Lidington, who is from the Defense Intelligencia and RUSI, had observed that it’s a real shame this happened because if you actually look at the party’s policies, they’re all pretty much identical. That’s sadly the case.

You can have national political life where pretty much all the major parties agree that the policy should be the opposite of what most people in the country actually think. That sounds like a rhetorical point, but it’s just borne out again and again by all of the calls that we have on this issue. Foreign policy is to be something for ideology professionals, something to be conducted in conclave. You don’t even find it out from the public think or whatever. It’s for specialists, and it’s nothing to do with the public. That makes it very difficult to challenge in terms of national politics.

Talia Baroncelli

So your book discusses the many connections between British and American intelligence, but also the U.K. think tanks and defense elite and American defense elite, and how a lot of former generals or people working for weapons manufacturers go on to head think tanks in the U.K. There is a bit of a congruence between the decision making and policy debating both within the U.S. and the U.K.

In 2010, in Britain, they created the National Security Council, which was meant to emulate the National Security Council in the U.S. The whole idea was to shift decision making powers and processes away from the more technocratic, bureaucratic foreign office and closer to the Prime Minister and the Prime Minister’s other advisors and ministers. How would you say the defense and military elite or establishment seek to emulate that of the U.S.?

Tom Stevenson

That’s a very important point. I mean, the creation of the National Security Council in 2010 was self-consciously done because the United States operates the National Security Council and because of the increased prominence of the National Security Advisor in American politics. There, there is a parallel. I think, in my view, also in the U.S. case, there’s been a long-term shift in terms of forming foreign policy as much as possible away from embassies in the State Department towards the National Security Secretariat and so on. But in Britain, there was a real feeling among the Senior Civil Service that it was important to try and emulate this. That attitude is one that continues in all sorts of interesting ways.

Very few people bother to read British declarative strategic documents, and I think it’s understandable as to why. But if you do have trouble to read them, you find interesting things such as that you’ll find passages that are more or less copied, if not word for word, then certainly concept for concept from the American, say, National Defense Strategy or National Security Strategy. Really an interesting reflection of how things are given to work. It’s not just a question of political subordination, but in this case, direct plagiaristic copying.

That idea is not just following the United States but copying it as much as possible. It’s one that infiltrates national life and has never been a scandal in any sense because it’s taken as a given that that’s how things either ought to work or in any case, do work. The National Security Council was temporarily in an off again, on again mode, but it was never a national press story or anything like that. It remains in place.

The idea is that even though foreign policy is pretty much decided in conclave, it should even be removed as far as possible from elected officials as well, or at least given over to a small number of elected officials who are to be led by the national security professionals within the civil service bureaucracy.

Talia Baroncelli

You’ve been watching part one of my discussion with journalist Tom Stevenson. In part two, we’ll speak about the war in Ukraine, as well as other forgotten conflicts such as the war in Ethiopia. Of course, we’ll speak about Gaza as well. See you then.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | TuneIn | Deezer | RSS

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter

Tom Stevenson is a contributing editor at the LRB. His collection of essays, Someone Else’s Empire: British Illusions and American Hegemony, many of which first appeared in the paper, was published in 2023.