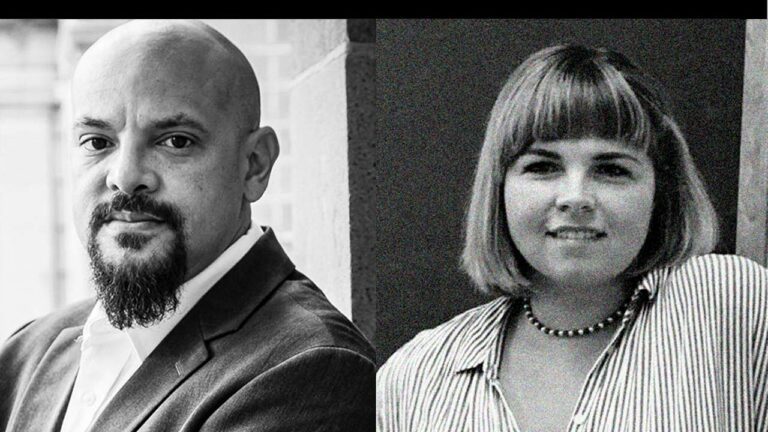

To intimidate the Soviet Union and prove to Congress the nuclear program should be funded, Truman dropped nuclear weapons on Japan to end the war; no scientist came forward to warn of the dangers to life on earth, says Daniel Ellsberg on Reality Asserts Itself with Paul Jay. This is an episode of Reality Asserts Itself, produced November 2, 2018, with Paul Jay.

STORY TRANSCRIPT

PAUL JAY: Welcome back to Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay. And we’re continuing our discussions with Daniel Ellsberg. Thanks for joining us again.

So Hitler didn’t want to risk burning the skies, burning the entire planet. But the American nuclear program was willing to take such a risk.

DANIEL ELLSBERG: Yes. You know, a more even controversial episode is that Heisenberg- the one who had made the estimate on atmospheric ignition as a possibility, but it would take too long for the bomb- indicated in various ways that he was reluctant to see a bomb coming to Hitler’s hands, even though he had joined the Nazi party and he was a very patriotic German, did not want to see Germany to lose the war. But when they learned of the bomb they were discussing being tapped, wiretapped, by the British where they were in custody saying, you know, we didn’t really want to do it. Had we wanted to, we would have seen through these obstacles and moved ahead.

American physicists took very great exception to the thesis presented by Thomas Powers on Heisenberg’s war, and so forth, that the Germans might have had more qualms than they did, in effect, than Heisenberg- you know, that was a very offensive idea. And he had gone to see Niels Bohr, the father of quantum physics, who came over later and helped the bomb project, in Denmark in a quite controversial issue. Heisenberg indicated that he wanted to see if Bohr could find a way of collaborating with the Western scientists in not bringing this bomb about at all. Bohr didn’t read what he was saying that way. He thought that he was feeling him out to discover how advanced the Americans were, the British were. Anyway, they were at odds on this point. And it’s definitely not settled as to what Heisenberg’s actual motives were on that point. But it is interesting how offended, how very … the Americans just dismissed any idea.

But actually, it isn’t that hard to explain, in a way, because two things. From the American side, the very plausible idea that the Germans were ahead just dismissed virtually all moral considerations from what they were doing. And that’s understandable. I couldn’t say that then or now, as I am now, I would have felt differently on that point in that light, whether they should move ahead to try to at least match whatever the Germans had. The Germans for that, from their side, didn’t have that consideration. They weren’t that afraid. They might or might not have been concerned about whether Hitler should have it.

But I will say this. Many of the scientists who were early on in this process, in particular Leo Szilard, fled Nazi Germany right after the Reichstag fire. He went and became an emigre in London, then in the U.S. because of what he saw Hitler would mean. He was sure that war was coming at that point. As he said, by the way, because he was sure the Germans would not resist. Not because they would be enthusiastic about what he was doing, but they wouldn’t oppose him effectively. And so he left Germany.

He had the thought that very year in 1933, the possibility of a chain reaction- the first to have that notion- that a heavy element being split by neutrons might emit more neutrons in an explosive, exponential chain reaction, and produce both energy or an enormous explosion. And he patented that idea and gave it to the Admiralty so that would not be known, he thought, to the Germans. He was very anxious that Hitler not get that idea. Later, he was- when he concluded, after uranium had been split. And he concluded with an experiment that he did that it did release extra neutrons in the course of this. He said he shut off the device that was showing this process with a sense that the world was sure to come to grief. In other words, he saw and others saw right from the beginning that this was something that could threaten civilization, and possibly the existence of humanity.

Two other points. In concern that the Germans would get it first, it was Szilard who drafted the letter for Einstein to send- his colleague- to send to Roosevelt, asking, telling about the German possibility, and that we should start a program so that the Germans did not get it first. So he was the, Szilard was a critical figure in getting the program started. Finally, working with Enrico Fermi, that I mentioned earlier, in Chicago, at what they called for cover the Metallurgical Lab, they started the first working reactor, then called a pile, that would demonstrate that you could control the reaction and produce plutonium. The reactors were essential to producing the Pu-239 that was eventually used as the core of the Nagasaki bomb. For most bombs, now. That night, the scientists who were present all celebrated with a bottle of Chianti, and Szilard stayed behind and said to Fermi, “This day may go down as a black day in the history of humanity.”

So, some say it was evident from the beginning that this had a potential of, you know, the most, when we say existential threat, literally the case. Not for the globe. Atmospheric ignition, even that would not destroy the earth. Just all the conditions for life on it. It would go like a rock through space. But that was, turned out with a number of tests, finally, that wasn’t a big problem. But destroying cities, that’s what it was made for, essentially. And by ‘42 the British had made their major project in the war, having been thrown off the continent earlier, the destroying of cities by firebombing.

PAUL JAY: OK. Before we go there, let me just follow up one thing. When Germany loses the war, and- as you said- there’s no other nuclear power, why didn’t the American scientists quit the program?

DANIEL ELLSBERG: They worked harder. When Germany ended the war they were pressed to redouble their efforts to get the bomb. Basically, people like Gar Alperovitz, but many others have concluded in the end, in order to have the bomb before the war ended. Which, with the war ended there’d be no excuse for demonstrating it on a city.

PAUL JAY: No, I get why the American military and the government wanted to keep it going. But why didn’t the scientists quit?

DANIEL ELLSBERG: They don’t have a good answer. Many of them have asked later- they were pressed to do it for national security. And of course, the Japanese too- for all they knew, like the American public, not knowing that the Japanese were discussing, and discussing with their ambassadors in Soviet Union and elsewhere, and with the Soviets their desire to end the war if the Emperor could be kept. There were other conditions that the Army wanted. They wanted more than that even after the bombs. But the Emperor and the people close to him and in the foreign ministry were ready to end the war.

Oppenheimer and the others didn’t know that. And they knew that the Japanese were fighting very hard. And the idea of ending the war sooner rather than later- they were actually contributing, in effect, to keeping the war going. Had there been no program, the- almost surely, had there been no bomb program, the offer to negotiate with the Japanese would have been earlier, instead of waiting for the bomb.

PAUL JAY: But the military wanted to be able to prove they had the bomb.

DANIEL ELLSBERG: No, it wasn’t the military so much. It was actually Truman and Burns, his foreign secretary. No, the military were in favor of making the offer, on the whole.

And in a matter of fact, here is an almost funny thing in retrospect. LeMay, who was in charge of dropping the bomb in the Pacific, was under Tooey Spaatz, who was in charge of all the Pacific Air Forces. Neither of them were very enthusiastic about the idea of demonstrating the bomb. As Spaatz put it later when he heard about the bomb, how could we justify a large Air Force when the atom bomb exists? Even against Russia, one plane does the work of 300. Now, we have 300. But how do you justify ever using them day after day to burn cities to the ground? And we were doing that. And we killed more people that way, by firebombing, on the night of March 9 and 10, 1945 in Tokyo than either Hiroshima or Nagasaki.

In the spring- or actually, after May of 1945 when the Germans had surrendered, so now we’re just facing Japan- for the first time, really, a committee was put together under James Franck. A Nobel Prize winner who, by the way, regretted his role and Germany’s role in introducing poison gas to the world in the First World War, and concluded in his own mind that if the occasion ever arose again, he would demand real consideration in his new country, the U.S., a role, a voice at least, in the policy implications of this scientific development.

So the Franck committee, which included Szilard, and as its rapporteur Eugene Rabinowitz, who later became the head of the Federation of American Scientists, and the editor of The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, with its doomsday clock. Rabinowitz was for many years the editor of that. And they concluded- as I said earlier, the first group really to be looking at it, thinking, amazingly enough, at the problem of where are we going with this? What are the implications of it? What does it mean for the world to have this weapon, and what can we do about it? Should have been done earlier. As I say, I believe if Rotblat had told people they were not racing Germany, they would have had this process months, six months earlier, in the fall, and possibly had much more influence on the final decision.

As I say, their recommendations, that the implications of the U.S. using this as a weapon in war- one bomb, one city- a weapon that would soon become much larger, there would be thousands of them, and would be supplanted by a weapon that was a thousand times more than this, that they thought should not be undertaken. That should be an effort in international control, and that required not having a monopoly of the bomb and using it in warfare. So we should at least, as Niels Bohr said, bring the Russians in as partners. The alternative being they would get it as adversaries within a few years in a cold war, which is what did happen.

So the front committee then met and had these conclusions, which did not get up through channels to the president. Rabinowitz, I learned only in the last couple of years in a thing that was not really published until quite recently, during the Franck Committee proceedings after the report was finished made the proposal that they should reveal, they should go beyond the bounds of security, and reveal to the public, the press and the public, not the details of bomb-making, but the fact that this enormous weapon was in prospect and was about to be used. He actually put that in writing. I’ve never seen anything in writing, ever, like that in government. In effect, a proposal by a government insider to leak.

Obviously, leaks happen all the time. not with much discussion, usually. people don’t want other people to know they might be a source. But in this case, Rabinowitz actually made that proposal, and nothing came of it. Then, however, he revealed in a letter to the New York Times in 1971, in June- a time very vivid in my memory because his letter came out in the New York Times while Patricia and I, my wife and I, were eluding the FBI. We were they say underground putting out the Pentagon Papers for 13 days while the FBI was searching for us. So I didn’t see this at the time. I wasn’t seeing the New York Times. I saw it many years later that while we were underground, he put out this letter saying, in the matter of Daniel Ellsberg that his under public discussion now- they were searching for me- he said, I myself spent sleepless nights in the spring of 1945 considering that I should reveal to the public this prospect- I’m paraphrasing here a little bit, but I remember the sleepless nights very well. And how his letter ended: I still believe that had I done so, I would have been justified. It would have been the right thing to do. Well, indeed, had Americans known about this, as Rabinowitz said later, I have no illusions that they might have supported the use of the bomb anyway. But at least they would have responsibility. They would have known what we were getting into.

And Szilard, by the way, was meanwhile putting a petition together, which eventually had more than 100 scientists, calling at first for not using the bomb even if it would save lives, and then to get more signers saying at least it should not be done without a demonstration, without the serious consideration of the moral concerns. None of this got to Truman. And in fact, Szilard was forbidden to publish the petition, that it had occurred, for decades. And when they finally did publish that there had a petition, they were unwilling to release the names of the scientists with the authority. In other words, that there was this alternative.

The point of all this is that time after time, I think, decisions were made in secret, at high levels, without real consideration of long-term implications of this or of alternative paths; without knowledge that the scientists had of what was coming, or where this might lead, and so forth. And there were people who saw the dangers of this so clearly, that they knew that civilization was in danger. I could go into the same story with respect to the H bomb. And in each case, each one decided to keep his clearance- they were all men- at the time. As a matter of fact, Hans Bethe’s wife was one person, who was a physicist, who when Hans told her about the H bomb they were imagining in 1942 said, do you really want to be part of this? And she’s the one person on record as sort of having told one of the scientists, think again about this. But Szilard, as I say, they all wanted to say, well, the Germans are in the process, or later the Russians are in the process, and they put aside moral considerations. But not one of them took the step of acting on his concerns and fears to bring the public and the Congress into the picture, and to have a discussion of whether this was the way that we wanted to go.

The bottom line for me is from the time they knew that Germany did not have the bomb- and I’m saying now the fall of ‘45 for the British, at least, and Rotblat- the overwhelming consideration about that bomb should have been how do we keep it from being an instrument of national policy, by us or anybody? Now, that was far from the minds of the people at the top. The idea of having a monopoly of it was so irresistible. There was no discussion whatever of not doing it at that level. They say the Franck notion didn’t get to them. And they didn’t- Franck didn’t tell them, Rabinowitz didn’t tell them, Szilard didn’t tell them. By the way, the FBI were afraid that Szilard, knowing his views, would leak on this, that he was under constant surveillance. But as far as we know, it didn’t occur to him to actually tell. C.P. Snow, who had been in charge of scientific recruitment at one point- later a novelist in Britain, I’ve read all his novels- commented, actually, on my case, in Esquire, after I was indicted for the Pentagon Papers, along with several other people. And he said, I would not- you know, I had sworn an oath not to tell secrets. I would not have done what Ellsberg did. However, I do have the feeling that if Einstein had been made aware of what was coming, he would have found a way to tell the public and bring them in.

It’s very interesting what if- you know, conjecture. Because as a matter of fact, Szilard did meet with Einstein in ‘45 to send his report, or his views, to Roosevelt. And before that was actually set up Roosevelt died, and he was sidetracked over to Burns, who didn’t sympathize with this at all. But he couldn’t tell Einstein why he wanted to see Roosevelt, because Einstein wasn’t cleared. Einstein was a pacifist. Not about World War II, not about Hitler. But he was generally a pacifist; later head of the War Resisters League. And they didn’t trust him. So he didn’t get a clearance, and he was never involved in the Manhattan Project, having laid the theoretical foundations for it himself earlier. Szilard didn’t tell Einstein, because that would have put his own clearance in jeopardy, frankly. And they warned him. Groves and others warned him. Keep in mind, this stuff is classified. Your clearance is at stake here, and so forth.

No one actually came out, in the end. Oppenheimer, others who opposed the H bomb, did not reveal to a totally unwitting and ignorant public or Congress what they knew, having been persuaded that that would be unpatriotic. It would be not gentlemanly. That’s what Dean Acheson told them. Don’t let them know why you are resigning from the General Advisory Commission. In fact, don’t resign at this time, because people will ask you why. Don’t tell them the reason is because an H bomb threatens the existence of humanity.

Fermi, on the General Advisory Commission at that time along with Isidor Rabi, signed a report saying the super, the thermonuclear weapon, is in itself an evil thing. It should not exist. And they even with Rabi proposed something like a test ban, moratorium. We won’t test first unless you do. But Truman overruled Fermi, and worked on the bomb; Bethe worked on the bomb. They all did, you know, patriotically and whatnot. And that’s why we’re where we are. Nobody felt, on the one hand, strongly enough to risk their own careers and their own status. Or to put in a little better light, their own identity as people who were trusted by the president to keep his secrets, whatever they were, was so important to them that it didn’t even occur to them that the public maybe ought to know about this. Where Rabinowitz is an interesting exception is he did wrestle with that.

PAUL JAY: OK. In the next segment of our interview we’re going to talk about those firebombings, and how in 1942 the British established the precedent for it. Please join us for Reality Asserts Itself with Daniel Ellsberg on The Real News Network.

Thank you, Dan and Paul, for this discussion. There are few topics more vital than these. Thus, I find myself disgusted to be confronted by a You Tube message that I have to sign in to see and hear what you have to say. Why? Because your content is “age-restricted!” I have objected to this rationale, since there is nothing that signing in will do to prove that I am older than eighteen years of age. And I do object to having to identify myself in order to receive your content. Would Vimeo be a better platform, perhaps?

At least I could hear the discussion, one of vital importance to the future of life itself.