On RAI, Paul Jay and David Swanson discuss the culture and economics of war. This is an episode of Reality Asserts Itself, produced December 16, 2013, with Paul Jay.

STORY TRANSCRIPT

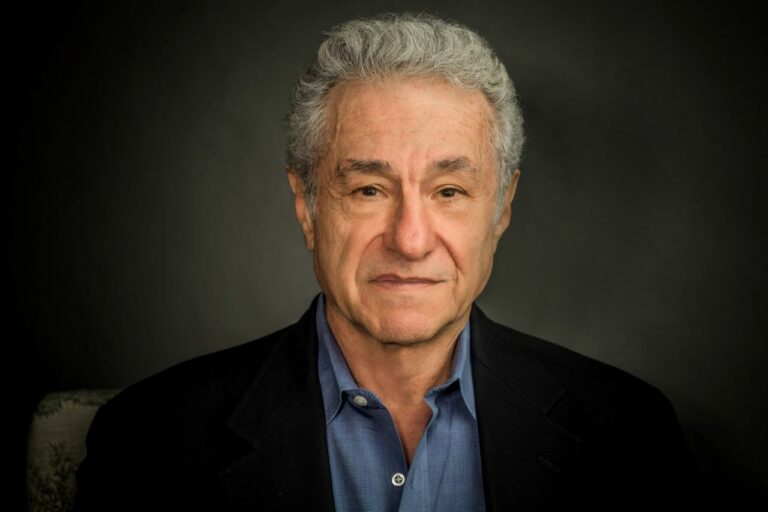

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay in Baltimore. Welcome to Reality Asserts Itself.

This is part two of our interview with David Swanson, who now joins us in the studio in Baltimore. David’s an author of many books, including War Is a Lie, When the World Outlawed War, and War No More. He blogs at DavidSwanson.org and WarIsaCrime.org. He works as campaign coordinator for the online activist organization RootsAction.org. And he’s secretary of peace in the Green Party Shadow Cabinet.

Thanks for joining us again.

DAVID SWANSON, ACTIVIST AND AUTHOR: Great to be here.

JAY: So we’re just going to pick up from part one. And you really should watch part one, ’cause it’s sort of David’s personal back story and more. But we’re going to pick up with David’s book War No More, and I’m going to read a few quotations and then ask David about them.

So these are sort of disjuncted quotations, out of order, but I think more or less on the same theme:

“The most significant cause of war, I believe and argue in the book”, says David, “is bad information about past wars. The abolition of past practices and institutions means the same can be applied to war. Look at the abolition of slavery, blood feuds, dueling, death penalty, decline of domestic violence and its public acceptance. The first step in abolishing war will be to recognize that it too is possible. The anthropologist Margaret Mead called war a cultural invention. It’s a kind of cultural contagion. Wars happen because of cultural acceptance. And they can be avoided by cultural rejection.”

JAY: So, David, explain all of this, because it lends–it leads me to think you’re saying this is primarily a question of worldview and outlook and not a view of what kind of economic system we have, who owns stuff, who has power in the society, that it’s–in terms of Margaret Mead, this quote that you use, is it’s essentially a cultural phenomenon. So if we can get over blood feuds, we can get over war.

SWANSON: I think there are other institutions and factors and cultural traits, from capitalism to racism to xenophobia, that feed into war and that work hand-in-glove with war and that open people up to arguments for war. But the only thing that historians and anthropologists have found that correlates with the presence of war is cultural acceptance of war. And while we don’t tend to glorify it as desirable the way that you heard back prior to World War I, we have a lot of people–the vast majority of people in this country think it’s necessary, think you can’t get rid of it, and some of those people think it’s part of human nature.

So it’s important for people to understand that war is relatively new, that in 100,000 years of this species, maybe 12,000 years have seen war, very sporadically. They’ll tell you there’s always been a war someplace. But of course there’s always not been a war many, many someplaces. Countries have gone for centuries without war. Countries have had war and done away with it.

When you look at how wars are decided upon, it’s completely random. The same incident can be used as an excuse for war or not, depending on the decisions of individuals, not of some major force or anything in our DNA.

And so when I say that the cause of war is people’s bad information about past wars, what I mean is that, you know, a majority of Americans think Iraq benefited from the war that destroyed Iraq. Americans think–.

JAY: Do they really believe that?

SWANSON: If you believe the polls, yes. And a strong plurality believe not just that the Iraqis should be grateful, but they are in fact grateful.

And I fault the peace movement somewhat for our overemphasis on the cost to the aggressor nation. You know, we want to focus on the self-interest. We want to tell people the financial costs, the costs to U.S. servicemen and women, although–as we call them, although I don’t know what the service is–and not enough on the overwhelming damage of the war to the other side. So, you know, less than 1 percent of the deaths in these wars are to Americans. But all the talk about the deaths in the wars is of the Americans. So people don’t understand that we’re dealing with one-sided slaughters, that it’s children and old people and women primarily who are dying in these wars. They don’t have a picture of that. And so they’re more open, therefore, to the idea that a war is necessary or that a war is beneficial.

And so I spoke in our earlier interview about the great victory of stopping the missiles into Syria. A lot of people opposed sending missiles into Syria because the Syrians weren’t worth it, they weren’t worth that benevolence.

JAY: But let’s go back, ’cause I think there’s kind of two different parts to this argument. Is war part of human nature? That’s one question which needs to be dealt with. Then, once you deal with that question–and let’s talk about that–then the question is: is war primarily a cultural phenomenon, or is it a culture reflecting the interests–fundamentally, economic interests–of various people, classes, strata within a society who will benefit from that war. So, I mean, the human nature one I’m sure we agree on pretty quickly, and I think–.

SWANSON: Not everybody.

JAY: Well, not everybody, so let’s talk about that a little bit, because the argument is that from the beginning, humans fight over lack of resources. Maybe they don’t fight much when there’s plentiful resources, but as soon as there’s lack of resources, tribes would fight each other, you know, go back into native tribes in North America or tribes in Africa, you know, and that all gives rise to this idea that people will fight, and that gives rise to war, and it’s who we are. So what’s your take?

SWANSON: Yeah, but it’s not true–vast areas of North America, Australia, other regions of the globe that didn’t have war until basically our current culture brought it to them, and, you know, tribes that anthropologists have reported on where you’ll ask a man, why would you not shoot that arrow that you use to hunt animals at that human who was coming to enslave you and your family members? Why would you not shoot it? And response is because it would kill him, and absolutely no comprehension of any other possible response. That is a cultural difference. That man has the same DNA that we have.

And so war is something that’s in our culture. The United States is vastly more militarized than the rest of the globe, and we are 4 or 5 percent of humanity. So you’re going to write the other 95 percent off as somehow not exactly human nature? I mean, war–.

JAY: Well, there’s–come on. There’s been–there’s wars all over the world. I mean, the African tribes did fight each other and native tribes did go to war with each other. But I think you got to add something–.

SWANSON: Nobody gets PTSD from war deprivation. People have to be conditioned heavily to participate in war. And they’ve gotten dramatically better at that conditioning over the past 75 years, but not at the deconditioning. And when they come back out, they suffer. War is not natural. And war used to be–.

JAY: But I’m not saying war is natural, but the culture of war–for example, you would have war dances amongst native peoples of North America, you would have war parties. There was a culture that under certain conditions you would go fight.

But I’m not suggesting it’s human nature. It’s at times when there’s lack of resources and the existence of your tribe is in jeopardy you might go and fight another tribe over lack of resources. But the culture mirrors what’s coming out of the economics, which is you might starve otherwise.

SWANSON: That argument makes so much sense that a lot of people have gone and researched it. And what they have found is that there is no correlation between population density, lack of resources, and war.

JAY: Well, then why did native tribes fight each–why did certain tribes often–not always, and not every tribe, but why did they go to war against each other?

SWANSON: Well, we should not expect universal rationality from them when we’ve seen our own insane politicians in Washington, D.C., go to war for irrational reasons. But certainly in some cases it’s over resources. In some cases it’s over grudges. In some cases it’s over territory. In some cases it’s over religious beliefs. And most wars have numerous motivations, and this hunt for the one true motivation is often in vain.

But there are Native American tribes that did not have war, as well as those that did, and they both had the same DNA. War for most of its history was male. Women have gone into war. I mean, since war has not been hand-to-hand combat, women have been just as capable of participating in war as men. Well, if women can join the war-making human nature, why can’t men leave it? Well, of course they can. There is no such thing is human nature. There’s human culture. And we have a culture that accepts war.

JAY: Yeah, I’m not arguing with that. What I’m arguing with is: where does the culture come from? The culture doesn’t come out from the sky. The fact–if you want to say war culture drives this, you still have to answer where war culture comes from.

SWANSON: It’s profitable for certain individuals and companies.

JAY: Well, you can–let’s go back in history. You’re talking now. Let’s start origins, because we’re talking about is it DNA or not. So you’ve got to talk, you know, in terms of development of humans as a species, with very, very few exceptions–and there are some exceptions–most of humanity, most of, you know, what we know of human history, there has been war.

SWANSON: Absolutely false. Absolute false.

JAY: Come on.

SWANSON: First of all, as I said, war is relatively new. You can find no record of it back more than 12,000 years. And this is a species that goes back at least 100,000 years, and there would be a record. I mean, this used to–this was the myth in the 1950s. The anthropologists would tell you that the animal bites on those bones were scars from war. No. We were dinner. We evolved as prey for animals. Right? And when our weaponized segments of our tribes killed off most of those large animals, they needed someone else to fight, to be maintained, to not have to grow food, to not have to do real useful work, just like Pentagon contractors. What did they do? They turned the hunters of the other tribes into their enemies and they had combats.

JAY: Yeah. I said since there’s been human civilization–and I’m not talking pre-civilization humanity, and I don’t know what–there might have been some fighting over resources at that time too. But my point is the culture doesn’t come–is not just some invention. The culture comes because of the economics, because of–if you want to take obviously–if you take colonialism, why did Europe go to war with each other and war against other countries as they conquered them? It was obviously an economic motive. It wasn’t just some cultural imperative. They wanted raw materials, they wanted markets, they wanted cheap labor, and they fought each other over who was going to have all these things.

SWANSON: And we like to laugh at the book that was quite popular just before World War I that explained that wars are not economically beneficial anymore and therefore won’t happen, but the argument was right. They’re not economically beneficial, not to a society, not to a country–to certain parties. And when you have decision-makers who are not acting on behalf of an entire population but on behalf of certain unscrupulous profiteers, then you have motives like greed.

JAY: Well, not just profiteers, but a whole class of people that profit if they win. It’s not just the war manufactures that profit. I mean, take the fact that the United States has the biggest military in the world and dominates through it. A whole sector of the society benefits.

SWANSON: A whole sector benefits, but it’s a narrow sector. And the people who we talk about as benefiting because they work in the military-industrial complex–they have jobs for the subcontractors to the Pentagon–those are real jobs, and they’re making real money, but those same dollars invested in anything other than military spending would give more people more jobs at better pay and jobs they could be prouder of. And so it’s actually a drain on our economy. I mean, the studies that have been done by the University of Massachusetts Amherst that look at what you get in the way of jobs for the same dollar if you put it in green energy or education or anything other than the military–.

JAY: And we’ve done these interviews, and if you search Bob Pollin’s name, you’ll find a lot of the information from these studies.

SWANSON: And nobody disputes this. There’s not another case. This is the economics. And tax cuts for working people, not tax cuts as we know them for billionaires, but tax cuts for working people produce more jobs than military spending. So it’s a negative, it’s a drain on the economy. You know.

And if you moved the money, you could save so much money that you could invest in a program of retraining and retooling so that no one would have to suffer. We don’t have to throw anybody out of work. Those are real people with real jobs, but nobody has to be damaged in the process. So Connecticut now, just in recent months having set up a conversion process to work on converting from military industry to peaceful industry in Connecticut, that should be a model for the other 49 states and for Congress, where such a thing hasn’t been heard of in decades. And that’s just the economic argument.

But what about all of the damage to our morality, to the humans killed and injured and traumatized, to the natural environment, to our civil liberties, to the loss of freedom and the wars for freedom? I mean, the benefits are incredible, but the economic argument alone does it.

JAY: The idea that it’s just a cultural phenomenon or primarily a cultural phenomenon, that if you can change enough people’s minds, you could put an end to war, I mean, is that what you’re saying? If you change the culture, you’ll end war?

SWANSON: Well, I mean, that sounds like we have a democracy or at least a representative government, and I’m not suggesting that. I mean, overwhelmingly, on all the big issues, the government in Washington goes against majority opinion. I mean, there’s no question. And war is not an exception in those terms. And we often have a majority against war in Congress and the president for it.

JAY: More often than not.

SWANSON: More often than not.

JAY: At least in the lead-up to war. Usually when war starts and the drums are beating, you can see a shift in public opinion. But like in the Iraq War, generally people are against war. Once the war starts, it seems to change.

SWANSON: Yeah, Afghanistan and Iraq, at the beginning, you had a majority–or close to it–in favor, and within a year and a half you had a strong majority saying it was wrong, never should have done it, should end it from then on out,–

JAY: Once it was a debacle.

SWANSON: –which didn’t mean end it, right? Because ending it is anti-troops and so forth. Once you’ve started it, there’s a section of the population and of course the congressmembers who say you have to continue it–even though it was wrong and it’s a bad idea, we still must continue it. So that’s why it’s so much better to prevent a war before it starts.

But, no, I’m not suggesting that you get majority opinion on your side and Washington immediately listens. I mean, we have to deal with the corruption of our government, but you get majority opinion significantly on your side and actively on your side, and you get opinion within the halls of power in Washington on your side, as we had there in a limited way for a limited time on Syria, and then war goes away. And there’s not some force of history or DNA or testosterone that’s going to stand in the way of that.

JAY: In a particular situation. But, as you said, there are people that benefit from war in the United States, and it’s a big stratum, certainly a big stratum of the elite, both in the military-industrial complex, certain sections of finance, certainly sections of the political elite, many of them who have alliances with other countries. We’re going to be doing a series on the Saudis and, you know, the amount of money the Saudis put into the American military-industrial complex, in terms of buying weapons, and their alliances with this, and other countries who make money out of war, that this is not just a cultural phenomenon if you want to change it. I guess what I’m getting at is you can’t change it just by changing culture. You have to change how stuff is owned and who has power.

SWANSON: You have to start by changing culture. I mean, we cannot have a democratic movement for a just cause when we don’t have a majority with us. That’s not a democratic movement. That’s a first step.

From there we need to make appeals to those sections of our economy and those constituencies that ought to share our interest. I mean, green energy companies that ought to want the money that’s going to the missiles and the bombs and the aircraft carriers ought to see the value of moving the money from the military to green energy, just as those in favor of investing in education and in all of the other places where the money could go. I mean, we think of the damage that war does in terms of killing people, but the money could save many, many times more lies than the lives that are taken. And that money, there are interested parties who can be organized to demand that money. There is another side to the economic pressure if we can organize it.

JAY: Of course one needs this cultural shift. You need, you know, a consciousness amongst a broad section of the population to change on these issues. But in the final analysis, you need to change who has the power to decide whether to go to war or not, and you have to, you know, wrest that power away from people who profit from war. I mean, it’s very, you know, embedded in the economic system and in the political system. You need to unravel that. I guess what I’m pushing back on: if you just talk about it as a question of beliefs and culture, you’re not dealing with the real politics of this.

SWANSON: Yeah. Well, I don’t. And I have put out a book called The Military Industrial Complex at 50 with a bunch of other authors where we make the case for the sort of coalition that’s going to be needed to shut down the military-industrial complex. And it’s going to need more than teachers. There’s no question whatsoever. We’re going to need incredible pressure to be brought against those forces that are pushing for war and imagine–falsely–that they are benefiting from war with this sort of crackpot realism where they’re destroying themselves and everybody else in a process that they imagine is benefiting them personally and defending us from the damage of their past exploits.

But we also have to take power away from a corrupt government in Washington and from a single individual in the White House, who now need not declare war, can send a flying robot with Hellfire missiles into anywhere on the globe and is teaching the rest of the world that that’s going to be acceptable and legal, and you have 80 other nations now with that technology. The United Nations says that it is making–there’s a special rapporteur, in his preliminary report, a guy who is the law partner of Tony Blair’s wife, says this is making war the norm, not the exception anymore. Jonathan Turley, a lawyer who’s by no means a radical and with whom I disagree on many things, says this is taking us back to the state of nature before the era of international law and civilization. We have gotten rid of declarations of war. We have gotten rid of congressional powers of war. We have gotten rid of even public knowledge of war. We have a single individual having meetings on Tuesdays, going through lists of men, women, and children, picking which ones to murder, murdering them, and justifying it to compliant liberal lawyers and human rights groups by calling it war, as if that makes murder okay because it’s on a bigger scale.

This is actually–we think of this as moving to more civilized war, more targeted, wore surgical, but it’s actually very, very dangerous in the sense of taking institutions like the United Nations set up to work against war and using them to justify and legalize a new and insidious and dangerous form of warfare, one that is not susceptible to our economic arguments because it’s cheaper than the other forms. So we have to make the moral argument that you’re killing children and grandparents and demand that our neighbors, our American fellow citizens, care about that.

JAY: Okay. In the next segment of our interview, we’re going to talk about is there such a thing as a just war, ’cause David doesn’t think so. So please join us for the continuation of our series of interviews with David Swanson on Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network.