This interview was originally released on January 28, 2014. Mr. Alperovitz tells Paul Jay there are existing models that point to what a new economy and politics might look like.

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay in Baltimore. And this is Reality Asserts Itself.

We’re continuing our series of interviews with Gar Alperovitz about what’s next. What might a new economy look like? And in this segment of the interview we’re going to ask Gar a question which we’re going to be trying to answer over the next few years: what would you do if you ran Baltimore? What would you do if you ran Maryland?

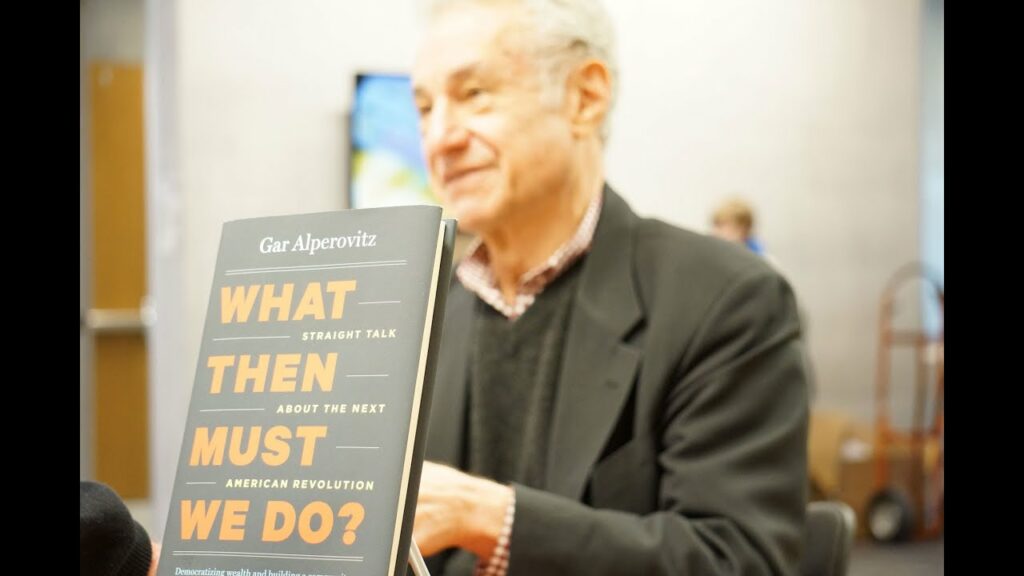

And now joining us again in-studio is Gar Alperovitz. He’s the Lionel R. Bauman Professor of Political Economy at the University Of Maryland, cofounder of the Democracy Collaborative, and the author of the book What Then Must We Do? Straight Talk about the Next American Revolution.

So, Gar, imagine this. Sometime in the next five years or so, five or ten, but within this kind of timeframe, there is a city council, a mayor, a state assembly, and a governor whose only agenda is the well-being of the majority of the people of Maryland and Baltimore. So let’s say you get to tell them what to do. I know this doesn’t quite jive with your participatory democracy thing, ’cause it wouldn’t be just you telling them. But anyway, for the sake of this, what are some of the things they might do? Now, dealing in a real world, where there’s going to be lots of opposition from people that own real estate and people that own various businesses and from people that control the finance sector. It’s not like you’re just going to have some clear field to do whatever you want. Within the real world, what would you do?

GAR ALPEROVITZ, COFOUNDER, DEMOCRACY COLLABORATIVE: Well, I would begin–I would build on what is already happening throughout the country, and partly here, which is opening a whole new direction. And you could use the power of the state and the power of the city, as is happening in partial ways all of the country. So almost everything I’m going to suggest is not abstract. It’s being built now. And you can look someplace else for examples.

So I would start at the city level. There are–all over the country, worker-owned cooperatives and worker-owned companies are being built. The city, and places like universities and hospitals with a nudge from the city, can really help this process along. You’re going to see a lot of it. Now, Boston and New York, where the progressive mayors are coming in already, you’re going to see them using city resources to help build up companies to begin servicing–as in Cleveland we talked about where there’s a gigantic system to support the hospitals, big industrial laundry. You’re going to need to produce greens and food, greenhouses. You’re going to have houses to build, solar installations. That kind of work is now being done by worker co-ops in parts, in structures that builds communities, nonprofit corporations being partners with them. That’s happening around the country in many cities now.

And using the power of the city to boost that, rather than some big corporation coming in or the next developer coming in, is well within the power now of any city. That’s ordinary business. The American business community’s done very well for itself passing laws of things that will help them. Worker-owned co-ops and our businesses, they’re–have access to this as well. But if you say we want to build neighborhoods and use this power not to make a lot of people rich but to rebuild the neighborhoods with part of the resources, that can be done city by city.

JAY: We were talking off-camera. In Baltimore and many other cities, they have these programs which are minority-owned businesses, and then 20 percent of construction contracting, if you have any business to do with the city, has to do go to a minority-owned business, where you could add to that or change it to be a workers co-op.

ALPEROVITZ: Sure. And what’s really interesting–and that doesn’t exclude the small businessman. He’s not the problem. And we’re finding in many cities where this is going on that small businesses say, that’s a great idea–people own a piece of it, they’re going to build the neighborhood, we’re going to have a better market. That can be worked in a positive way. And you can get the big hospitals and universities, which are big players, along with the new city council that says, this is the direction we’re going.

JAY: Well, you can and you can’t. I mean, there are some situations, and Baltimore is one of them, where some of the universities are the biggest landlords or almost the biggest landlords in the city, and the plans they have for property development are quite at odds with what the community wants. So it’s not so simple.

ALPEROVITZ: Well, that’s where the politics comes in. In some–they can help in some areas, and some areas there’s going to have to be some political change and some decisions made. And in some cases they can help, and in some cases there’s going to be a confrontation.

JAY: But Baltimore is rather unique in–is that maybe the majority (I think it probably is the majority) of businesses and employment in Baltimore are already either publicly owned or are nonprofit universities and hospitals.

ALPEROVITZ: No, that’s true in many parts of the country. And a lot of taxpayer money goes into all those institutions. So if the government is a–political control of the government says, we want to use that taxpayer money to help move in a direction that benefits a much larger group to own and build new models of ownership that are democratic, that can be done. That’s not beyond what’s happening. It’s a political question. It’s also educational. The press doesn’t cover what’s already happening around the country. We could build on it.

JAY: One of the things that I think people have focused on a lot–and it goes back to–earlier we talked about–you talked about how General Motors and Chrysler essentially had been nationalized, and if that had been then given a public interest mandate, you could have really built some piece of the new economy. Instead, they just restructured lower workers wages and handed it back to the private sector.

ALPEROVITZ: That’s right.

JAY: But the other sector that essentially was nationalized and again just handed back was the banking sector. And if you’re really going to change things, you’re going to have to do something with how finance, how loans take place. And what could be done at a city and state level there?

ALPEROVITZ: Again, we’re not–this is no longer rhetoric. The state of North Dakota has had a publicly owned bank for almost 100 years now, and it is public. It makes money for the state. Twenty states have legislation introduced to set up public banks. That can be done. You can set up a city-owned bank, or, minimally, you can take city tax deposits and put them in banks that will invest in the city. That’s also being done around the country.

And all of this is evolving. It’s going to be more and more democratic rather than less as cities began to experiment more and more with this and states begin to experiment. And the name of the game is: how do we rebuild our communities and do it in an ecologically sane way and change the ownership structure?

The ownership concentration–political power goes with ownership in a big way. The top 400 people–just think about this–in the United States, 400 people–you can get them into, you know, a big classroom or a church easily–they have more wealth, they own more of the country than the bottom 180 million taken together. You want to change politics, you’ve got to change ownership in a democratic way that doesn’t just rebuild that.

But what’s exciting about what’s going on around the country is almost in every sector you can find land trusts, you find city government. There are 2,000 cities that–2,000 electric utilities are owned by cities. Many, many practical things.

JAY: There’s something going on in Colorado on that front, is there not?

ALPEROVITZ: Yes, and that’s another thing. They’re beginning–they challenged, in Boulder, Colorado, challenged the existing private-owned system, and moving it to public.

JAY: Electric system.

ALPEROVITZ: Electrical system. Moving it to public. Two referendums. They won the first by a very marginal–they won the second by a lot. And why? Because people decided to make something happen. So that’s at this level.

Most people don’t realize that the state of Maryland, like 27 other states, currently invests in companies and takes ownership shares in start-up companies. The state of Maryland has stock positions in hundreds of companies, and they make money for the taxpayer. Well, that’s another–and they can also begin influencing the location of those companies–stay here so we can stabilize jobs in our communities. No reason you can’t do that. So we really begin to build a stable economic base. That’s something that can be built on as well in many parts of the country.

So what you begin to look at is practical things that already exist, taking them to the next stage, rationalizing them, and putting them together in a way that’s strategic, that has a plan. Cities can do that. States can do that. And what really is at work here is education, political development, politics, and also practicality.

I think the key and one of the things we’ve learned in working around the country is the things must be practical. They must be built on models. And when they are, you’d be surprised at the constituencies you get when you drop the rhetoric and begin talking about actually something that makes sense to people based on something that’s happening around the country.

JAY: I mean, one of the questions that’s most urgent and pressing and at top of most people’s minds in Baltimore is the school system and how to have a safer community.

ALPEROVITZ: Right.

JAY: And, of course, the things are connected–the war on drugs or the failure of the war on drugs, police community relations, which on the whole are pretty terrible in Baltimore.

But all of that goes back to that if you have a long-term chronic poverty, you cannot fix the school system, you cannot deal with most of the other issues, and if–you know, kids getting out of school, if they’re hopeless and the odds of getting a job of any kind, or at best some horrible low-wage job–you know, how do you break that whole culture? And, you know, they keep talking about doing it through the private sector, but, of course, after decades and decades it’s clear it isn’t going to happen.

ALPEROVITZ: Yep. That’s exactly why these experiments like the one in the city of Cleveland in this neighborhood of unemployment with 40 percent–that’s what we’re talking about. So either we have a concentrated strategy to rebuild and change who gets, owns, and the benefits of that ownership, or the problems get worse. You want to get to the drug problem, you want to get to the schools, you want to get to poverty, you’ve got to have a whole strategy that not only takes on jobs, quote-quote–there are no job programs. There’s a money for–. But the power relationships that stop some of these programs have to be taken on. And that means changing the structure of ownership, but doing it intelligently.

What’s very exciting about–as I said earlier, these experiments are now developing in many, many–we’ve got a lot of new mayors come in just this last election [crosstalk]

JAY: Yeah. Talk a little bit about the use of eminent domain in Richmond, California.

ALPEROVITZ: Well–and Richmond is very interesting in that it’s a progressive city standing right next to a big oil company.

JAY: Chevron.

ALPEROVITZ: Chevron. So there–it’s a difficult situation. They’ve had a lot of confrontation.

But, you know, what happens is the banks have these houses that are underwater. They prefer people to keep paying the mortgage on what the old value was. What ought to happen–and many–this is not novel–is that if you were to sell those houses on the market, you’d know what the value would be–half that value. Then the people could buy it back at what it’s actually worth. The banks prefer to do it this way.

What the city of Richmond has recognized, and it’s true in many parts of the country: those decaying houses are dropping the values of many other houses. So the city has a public interest–get this–a public interest in stopping that process. Eminent domain, which means the city can force the banks to sell those houses to the city, not at a loss, but to sell them–fair market value–. Eminent domain is used all the time for commercial development. That’s how development, real estate development’s done in many parts of the country. Richmond has used eminent domain to force the sale of these houses at market value rather than at the inflated value they’re trying to get the homeowners to keep paying on. So they’ve won that battle.

Now there’s another battle: who will finance the purchase of those housing? And the banks are resisting.

So here’s a place for some kind of wealthy foundation or some wealthy individual–I keep looking for this–to go in and help Richmond out. These are decent investments. These are not bailouts. Those mortgages are at fair market value. They will pay what any mortgage will pay. The banks are resisting for political reasons. But this is an example of what can be done.

JAY: But it also gives the next step, which is the need for public banking.

ALPEROVITZ: Actually, public banking is the next step. And there are some quasipublic banks. There’s–as I said, in North Dakota there are some experimental, some very interesting–.

JAY: And credit unions.

ALPEROVITZ: Credit unions, nonprofit banks.

Credit unions are key to this. Most people don’t realize this. A credit union is a co-op. It’s a one-person, one-vote bank. That’s all it is. If you put them all together in the United States, all of these one-person, one-vote banks, credit unions, have as much capital as any of the big New York banks–$1 trillion. It’s now being used for non–very boring–housing and auto loans, mainly, a little bit for business. They’re restricted. The banks have made sure to restrict them for business. But they can do housing, and they could be using their strength.

Now, it’s interesting, ’cause it gets you into the politics of this: who runs the credit unions? Nobody ever goes to the board meeting. They’re boring. And nobody goes to the elections for the board members. Some people, light bulbs have gone on amongst some of the Occupy people, the older people that were involved: why don’t we just go and elect our own boards? These are one-person, one-vote banks. In some parts of the country that’s actually happening. That’s another source of power that could be used to tomorrow.

JAY: Okay. This is just the beginning of the discussion. We are going to invite Gar back. We’re going to have town halls. We’re going to have debates. This is the beginning of a big process about what would you do if you ran your city, what would you do if you ran your state. And someday we’re–I shouldn’t say someday–we’re also going to have the discussion about, you know, what would we do if we ran the country, ’cause I think everyone understands what I mean by we, and we don’t run the country.

So thanks very much for joining us, Gar.

ALPEROVITZ: Thank you.

JAY: And thank you for joining us for what is the beginning of, I hope, a very fruitful discussion that we hope leads to some real change.

Thanks for joining us on Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network.

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter

“Gar Alperovitz is an American historian and political economist. Alperovitz served as a fellow of King’s College, Cambridge; a founding fellow of the Harvard Institute of Politics; a founding Fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies; a guest scholar at the Brookings Institution; and the Lionel R. Bauman Professor of Political Economy at the University of Maryland Department of Government and Politics from 1999 to 2015. He also served as a legislative director in the US House of Representatives and the US Senate and as a special assistant in the US Department of State.”