On Reality Asserts Itself, Mr. Shallal tells Paul Jay how speaking out against war led to his passion about schools.

This is an episode of Reality Asserts Itself, produced March 26, 2014.

STORY TRANSCRIPT

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay in Baltimore. And we’re continuing our series of interviews on Reality Asserts Itself with Andy Shallal. He’s the owner of Busboys and Poets group of restaurants–will soon be seven restaurants in the Washington, D.C., area–and they’re more or less the hub of most things progressive in Washington, D.C. And Andy now joins me in the studio.

Thanks for joining me again.

ANDY SHALLAL, D.C. MAYORAL CANDIDATE: Thank you so much, Paul.

JAY: So just quickly again, Busboys and Poets was founded in 2005. In 2003, Andy founded Iraqi Americans for Peaceful Alternatives in opposition of the invasion of Iraq, and he’s been very involved in the peace movement. And we’re going to continue our discussion.

So, before we move on, I got to do a–what do you call it?–a lie of the land, a rules for this interview, ’cause we’re starting to move into territory that involves the elections in D.C.

Now, we planned to do this series of Reality Asserts with Andy before there was an election for mayor–that Andy was involved with, anyway. We–the idea for us was just he’s an interesting person and Busboys and Poets is interesting and we wanted to know more about Andy.

But the timing worked out that it actually happened while Andy’s running for mayor. So, as we haven’t yet interviewed anyone else running for mayor–although I have to say we have invited now most of the other candidates, and if any of them take us up on it, we will interview them as well, but that being said, we’re going to create a few specific rules about this, which Andy has agreed to.

The main rule is Andy can’t say anything negative about any of the other candidates, he can’t be critical of anyone’s record or anything, ’cause they’re not here to defend themselves and they may not be here to defend themselves. And I don’t know that Andy would have spent time doing that anyway. But the deal is he’s going to be constructive. As he talks about his ideas about public policy, it’s all about what his vision of solutions are, his vision of the future. And we are not going to trash anybody else who’s running, or even talk about things in the news about various people who are running. We’re going to keep it clearly to what he thinks are solutions to the problem.

And that being said, let’s get started.

SHALLAL: You really want me to be political and not trash anybody? That’s an oxymoron.

JAY: I know it is not the American way.

SHALLAL: Really.

JAY: You know, I used to produce the main debate show on CBC in Canada, called CounterSpin, and we would invite leaders of parties–you know, we were on CBC, so we got very senior people–and we had that rule even in the middle of the election. They were not allowed to say a single negative word about another candidate. They could only talk about their constructive vision for policy. And it’s unfortunate how little they had to say.

SHALLAL: Really. That’s true.

JAY: Okay. But we’re not going to start immediately with policy stuff, although we’re going to kind of go there.

Off camera I was asking you what’s another important moment, formative moment in your thinking about how you look at the world, your politics, and you were talking about your kids and them going to school. So tell us that story.

SHALLAL: Well, you know, when you come to this country, it takes–and you’ve already established your identity somewhere else, it takes a while for you to give up that identity and start a new one. And so, when you give up your old identity, you want to come into something that you feel really good about. You know, like I always say, I’m an American by choice, so I really am an American that takes my Americanism very seriously. And so I want to make sure that we hold this country to its values, to all the things that make it a desirable place for people to come to and live in, so the idea that once you start asserting yourself and become an American you start looking much more sensitively to how we do things in this country.

So I got very involved in my children’s schools; all my kids went to public schools, and so I got very involved in them. And I remember being PTA president and, you know, getting involved in all levels of the school system, working with school boards, working on commissions, working on creating a better environment for kids, a more diverse environment, etc.

So one year–it was 1996, I believe, when Clinton was getting ready to do his second term–there was a moment there where there was a lot of friction between Iraq, Saddam Hussein, and the United States. And Clinton, I think, ordered some strategic attacks, some Tomahawk missiles that were sent into Baghdad and hit the airport at that time. And I was very upset about it because of–again, the collateral damage is always not talked about. And, in fact, during that one attack, Iraq’s top artist, Layla Al-Attar, was killed and her daughter was blinded. They just happened to live not far from the airport, so she became the collateral damage for that attack. So I was very outspoken about it.

JAY: It’s also, was it not, the period of sanctions against Iraq–

SHALLAL: Yes, there were sanctions, of course, throughout the ’90s.

JAY: –that some people suggested had killed tens of thousands, some people even say hundreds of thousands of children.

SHALLAL: Very damaging, very damaging. There was, you know, medicine that was withheld, some basic needs, like pencils and things like that, that were, you know, withheld from being able to, you know, be shipped to Iraq. So it created all kinds of hardships for people.

So I was very outspoken against that, very outspoken against the attacks.

And I remember that one year when the attacks were happening there was this fervor, anti-Iraq fervor that was going on, and I didn’t feel comfortable with it, you know, having kids in school who identify as part Iraqi at least. And I remember my daughter, my oldest daughter was talking to me about Iraq and trying to figure out what is this Iraq thing we’re talking about here, why are Iraqis such bad people, and, you know, didn’t realize that we are Iraqis too. You know, they’re not bad people. It just–the policies are the problem here.

So I went before her classroom to try to talk to the students about Iraq and Iraqi culture. I didn’t want to be political–they were fourth graders. You know. So I wanted to have that opportunity to share the culture with the students. And the teacher at that time said, I don’t think it’s a good idea for you to do that. And that was a moment. It blew my mind. I said, what do you mean it’s not a good idea? This is actually a teachable moment. This is what teachers live for, that moment where they can connect reality with what they’re teaching. Wouldn’t that be the perfect time for me to do that? And it had to be pushed up the chain to the principal, and then the communications director of the school system, and then the superintendent. I thought, wow, I want to talk to a fourth-grade class about Iraqi culture, and suddenly I have to talk to the superintendent of schools in order for me to be allowed to do that. What other parent would put up with that?

And so I really got very, very upset and ended up, you know, asserting myself. I said, here I am, PTA president. I, like, painted walls in the school. I served, you know, at the fairs. I baked cakes for the school.

JAY: I mean, it’s a little bit of a softball question, but do you think if you had gone to talk about Israeli culture, you would have run into the same problem?

SHALLAL: Well, what prompted me, actually, to talk about Iraq, even, was that they were promoting military activism for kids. In fact, there was a parent that came who happened to be in the Navy, and he was promoting career opportunities in the Navy to fourth graders. And I thought, well, he can do that, but I want to be able to come and also talk about Iraq. You know. And that was really–so he was completely allowed. He didn’t have to go through the chain of command. He didn’t have to go through the principal and the superintendent. He was more than welcomed.

And here I am, talking about Iraq, and suddenly I became the outcast. And I realized how easy it is for someone who has asserted himself into a culture, became an American by choice, values what this country has to offer, and suddenly I felt like an outsider.

JAY: Again.

SHALLAL: Again. And it was very disturbing, frankly, very emotionally disturbing to me to see how easily that could be taken away, that you’re always looked at with those suspicious eyes–you’re not really an American.

JAY: Yeah, because really being an American means really believing in the religion of Americanism. And you don’t critique America when it’s at war, you don’t talk about the enemy–

SHALLAL: Absolutely.

JAY: –in any positive way during a war, ’cause that just ain’t American.

SHALLAL: And to me that was the complete opposite of what an American is, that an American should be one that questions everything, questions their government. In fact, I always feel like people like me are the insurance policy for American democracy. We are the ones that hold this democracy to the standards, ’cause a lot of times people in it don’t really appreciate it or recognize it.

JAY: So we’re going to segue now into some of the issues you’re dealing with. And the schools is a big passion for you. You said you were president of the PTA. You got into this whole, you know, fight over just speaking to a class. This has been a preoccupation of yours for a long time, and, I would guess, mostly ’cause you’ve got two kids, you have two daughters, and I know–.

SHALLAL: And two sons, actually.

JAY: And two sons.

And I know that it wasn’t in fact–you know, recently I had–I guess people that watch know we had twins recently, so now all of a sudden I’m thinking about schools in a completely different way. It’s not, like, just some–you know, one of many issues; it’s like, where are these kids going to go to school in a little while?

So your ideas about education make it a bit personal how you came to some of these conclusions. And then what would your vision be? What would you do to fix the school system?

SHALLAL: Well, I live in D.C. now, so the school system is always at the forefront of discussion in D.C. We are in a situation where we have a city that has some of the most educated people in the entire country. We have more degrees per square inch than any other city in the United States. And yet schools are failing. In fact, in some areas, 60 percent of the kids drop out before they finish high school. Fifty percent of them come out functionally illiterate. And if we were a state, we’d be number 51. That is not a good record.

And schools are important for a number of reasons. First of all, if you have kids, certainly they’re important directly to you. But even people that don’t have children see schools as something very significant in their community, because oftentimes school determines so much. They determine how safe a community is, how clean it is, how tightly knit the neighborhood is. All of those things revolve around a school building. So it’s really important to have good schools. And, clearly, they determine the value of your home. That’s for sure. Certain school districts are coveted, and the homes are much more expensive to buy because of that reason.

So I have a real passion for schools because I do believe that schools are the foundation of a community, of a society.

JAY: And given how much trouble most city school systems are in, unless you’re talking some top-tier private schools and such, do you think there’s a sort of–when I say they, I mean, you know, in the American elite–they’re quite happy with a kind of two-tier educated society. You know, you’ve got the upper-tier private schools that are trained–like, if you go to New York, especially, they’re–you know, kids are being trained to become the new rulers of the society.

And to a large extent, you know, it’s interesting: in this information age, you can actually be completely uneducated and still be quite productive. Like, I made a film in Afghanistan, and I met guys that did not know the Earth was round, did not know where Germany was on a map, couldn’t find it, but they could drive a modern truck, they could work an AK-47, like, they could understand a certain piece of technology.

So, I mean, do you think there’s, like–they don’t want people to be in the know in any real way?

SHALLAL: I think it’s really–it’s hard to know what intentions are, obviously. But I think people that are moving to cities now–and more and more people are moving into cities, more people that have money, more people that have power and influence are moving into cities. They expect more. So that’s why there’s been this huge changeover about education suddenly in urban environments, because for a while we just thought urban schools just didn’t matter. You know, the people that were there didn’t matter. Their voice didn’t matter. They didn’t have the power, they didn’t have the money, they didn’t have the clout, so it didn’t matter. And now that people are moving into cities that feel it matters–yeah, I want my kids to go to good schools, and I’m not interested in spending $40,000 a year to send my third-grader to elementary school. That’s what’s happening in many of those cities. It’s happening in D.C. So the focus on schools, unfortunately, has started because there’s a certain class of people moving into urban areas.

JAY: With gentrification.

SHALLAL: Absolutely. So what’s happening in D.C., for instance, if we want to look specifically about one area that I’m very familiar with now, is that in D.C. the achievement gap has gone off the charts. The fact–the achievement gap between black kids and white kids has gone off the charts.

The fact of the matter is that if you look at the school system in general, you see an increase in numbers as far as standardized tests. Now, I’m not saying standardized tests are the be-all and end-all. They shouldn’t be. I’m not an advocate of just standardized testing as the only matrix to judge a school. But I am saying that if we’re going to use that–and that’s what they’re using now to determine what a school is doing well or not well–but let’s use that matrix that they use. So if you use that matrix alone, you see that in D.C. public schools there’s been an increase. We’ve been doing well year after year since education reform in 2007.

If you peel one layer outside of that, you see that the increase has been solely due to demographic changes, not that we’re doing better. In fact, black kids have flattened out. The gap between black kids and white kids today is double what it was in 2007 when education reform started.

JAY: Why? How did education–is educational reform itself one of the reasons for it?

SHALLAL: No. Education reform did nothing to improve the school system is what I’m saying. The fact of the matter is you have demographic changes that have come in in some schools.

JAY: No, but I’m saying you’re saying it’s actually worse now.

SHALLAL: Well, the gap is worse. And the reason why the gap is worse is because black kids have not changed at all. They’ve stayed flat. It’s like we have done nothing.

But what we’ve done is we’ve closed a lot of schools, we’ve fired a lot of teachers, we’ve restructured schools, we’ve privatized schools, we’ve opened a ton of charter schools. And all of that has resulted in zero advancement for the kids that need it the most. The fact that you have kids that come in that have the parental support, that have the wraparound services that they need, that have afterschool programs, that have a rich environment outside the school system, of course they’re going to do well. That’s given.

JAY: So the schools are doing better when they’re dealing with people in gentrified areas–

SHALLAL: Absolutely.

JAY: –and have that class sophistication and demand for that kind of education.

SHALLAL: Absolutely. And the schools that are in areas that have not gentrified yet are doing very, very poorly. So we’ve created this double-tier system.

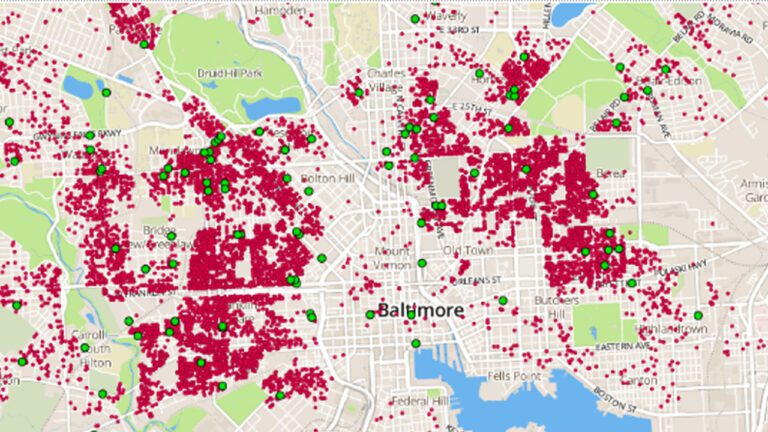

JAY: And I know from what we’re seeing in Baltimore–and I’ve seen other kinds of studies–sometimes that’s quite deliberate, in the sense that people that are sitting on real estate and want real estate speculation, they want conditions to get so bad people just leave, and then you build a nice grade school and bring in a whole different kind of class and, often, color of people.

SHALLAL: And that’s–I think that’s the rumble under the surface that people are really upset about, and that’s why there’s been a lot of tension, racial tension especially, in Washington, D.C., because people feel that tsunami coming. You know, it’s like what happened in Southeast Asia when people that were on the beach were hearing this rumble but they couldn’t figure out what was happening, but they were afraid, and there wasn’t ground high enough for them to go to, and suddenly they’re washed away.

JAY: And the rumble now is?

SHALLAL: Is the gentrification is moving, that people feel like all of a sudden the streets are getting cleaner, all of a sudden there’s new buildings going up, all of a sudden school buildings are being refurbished and renewed.

JAY: And where is everyone who used to live there?

SHALLAL: Everyone’s getting pushed slowly, slowly out. Prices are getting more expensive. It’s getting harder to live there. And so they get moved out.

JAY: I mean, it’s very relevant to Baltimore, because a lot of people think that’s the plan.

SHALLAL: Well, I think in most urban areas, in most cities that’s happening. You know, people have realized that cities are valuable real estate. They’re important. You know, they’re centers of power. And so let’s push everybody else–.

You know, for a while there it was the opposite–you know, went out to the suburbs. And now people from the suburbs say, hey, wait a minute, this is not a good lifestyle. It takes too long to get there. You know, I have to fight traffic. I have to drive for a long time. My quality of life has diminished. Wouldn’t it be nice if I lived walking distance to my office and walking distance to the coffee shop and walking distance to my friend’s house?

JAY: Right. So everybody wants to fix schools–but fix them in whose interest?

SHALLAL: Right.

JAY: So in the next segment of our interview, we’ll talk about how you want to do it.

So please join us for the next segment of Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network.