This is an episode of Reality Asserts Itself, produced on June 15, 2014. Mr. Johnson says the compulsive pressure of money in politics has led to an abandonment of rules other than rules which transfer risk onto the back of the public.

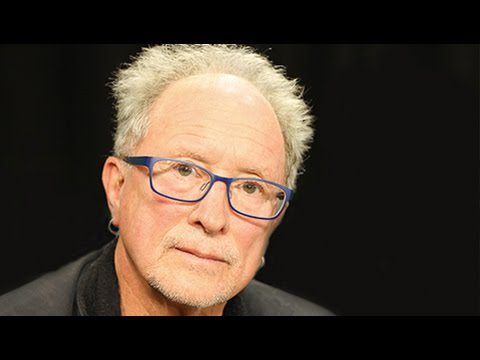

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay in Baltimore. And welcome back to Reality Asserts Itself with Rob Johnson, who joins us again in the studio.

Thanks for joining us again.

ROB JOHNSON, EXEC. DIRECTOR, INSTITUTE FOR NEW ECONOMIC THINKING: My pleasure.

JAY: One more time, Rob is president of the Institute for New Economic Thinking and a senior fellow and director of the Global Finance Project for the Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt Institute in New York. He was managing director at Soros Fund Management, where he managed a global currency, bond, and equity portfolio.

Thanks for joining us again.

Just picking up from your biography (and if you haven’t watched parts prior to this, you are really going to have to to pick up on the story), you made a big play with Mr. Soros in England. You made some others in Asia. You made a lot of money. You had time to sail. You went back into finance again.

When I–as I’ve known–come to know you over the last, what, three years, I guess, or four we’ve been interviewing back and forth, you are one of the most uncompromising, savage critics of the finance sector, of the politics that that power engenders. And you speak really unhesitatingly about all of this. That ain’t the same guy that made the play with the Bank of England.

JOHNSON: It’s not clear.

JAY: How do you get from there to here?

JOHNSON: Well, first of all, I think I’m a civilized critic of savage behavior rather than a savage critic.

But I think that my sensibilities when I was a financial speculator are not at all different, or when I worked in the Senate Banking Committee, than they are now. I think the world of permissiveness in finance, the lack of enforcement, the deterioration of regulations, the so-called revolving door where regulators can leave and go to the private sector and make a lot more money, all of these things are in much worse condition than when I worked in the Senate or when I worked with Soros.

JAY: But the seeds of it was all there.

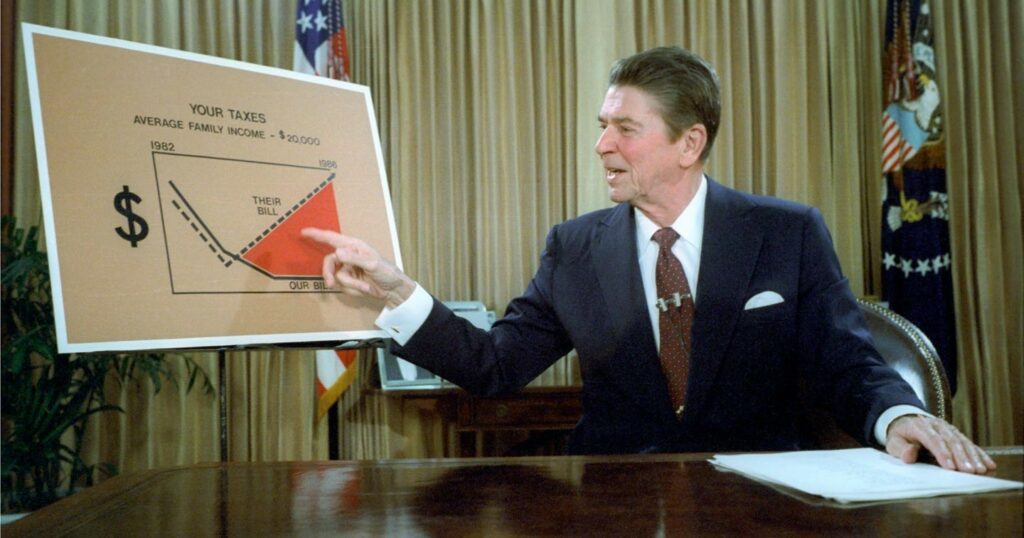

JOHNSON: Not entirely evident ex-ante, but it continued to accumulate, accumulate, accumulate. And it’s almost like a amplifying feedback loop: the stronger it got, the more power they had, the stronger was the pressure to unshackle things, and the more egregious the behavior could become.

JAY: Was the problem then not for you a system that allows you to break the Bank of England? Is the problem that the finance sector has gotten so out of control that it threatens the system itself?

JOHNSON: I think that the compulsive pressure of money in politics has led to almost an abandonment of rules other than rules which transfer risk onto the back of the public, to socialize the risks taken by the financial sector.

JAY: Which is the bailouts.

JOHNSON: And the bailouts of TARP were a manifestation of it. The non-restructuring of mortgages that were underwater was a manifestation of that, the role of the central banks in large balance sheet–buying things off the balance sheets of others, which were necessary to make markets work again.

But I do think we were in a period that required much more profound reforms to make a proper market. You know, there are a lot of hedge fund managers that I’ve known over the years who do not like a structure of these markets around the too-big-to-fail banks and constellation of subsidies.

JAY: Why?

JOHNSON: ‘Cause they think society is right to see how distorted this is. They think they have talent. They think, as financial investors, a high-integrity, fair market is something that they can make money from, practice their craft. And they see the political outrage as both legitimate and threatening to whether they can continue as investors.

JAY: In 2011, you invited me to an INET conference in Bretton Woods. And I’ll never forget the opening. We were in this kind of hotelish room–not hellish room; hotelish room.

JOHNSON: It’s where the original Bretton Woods conference was held, in that room.

JAY: Right. And George Soros is opening things. And his opening words, he looks out for a long time at all of us in the audience, and his opening words, if I remember correctly, were, I’m bewildered. And his point was, he says, I cannot understand that the system is clearly out of control. The way finance is operating (I’m sure I’m paraphrasing him here) is so destructive, and no one will listen to us as we try to caution them about the need for doing something about this.

In terms of your work in INET and your voice and others who you mentioned just a bit ago who are involved in finance and hedge funds who share your view that this is self-destructive in the end, you seem to be marginal voices, as far as I can see. You guys–I mean, George Soros one of the most successful, you know, individual in the history of American finance, can’t get listened to. He says he’s bewildered how no one will listen.

JOHNSON: Well, look, the top banks, say, the top six banks in derivatives earn every year more than George Soros’s net worth. He’s a very wealthy man. At the same time, in relation to the entire scope of the financial industry, many of whom like this unbridled system, he’s relatively small financially. George Soros and INET don’t pay advertising for all the major financial newspapers. We earn our media at times. But people who pay every day for advertising in the private sector media, you know, what you might call tend to bend the ear of the editorial board. So I’m not at all surprised, despite his reputation and expertise or the fact that I’m an experienced practitioner, that our voice is somewhat diminished or, you know, a sidebar relative to that central game. The power-political economic interests are not in agreement with us. And that plays a role.

JAY: And they, as you use the word, have captured the politics.

JOHNSON: Well, the politics and the media to some degree.

You know, politics and media are both a little more anxious about the unbridled financial sector, ’cause there’s a lot of popular outrage about too-big-to-fail. There’s a lot of popular outrage about increasing inequality, where many of the top paychecks are in the financial sector. I think it’s an important thing. We do need financial markets. At some level it’s–I’m not anti-financial markets. I’m anti- this particular architecture which places to big a burden in the social contract on the back of society relative to the financial firms that are taking risk.

JAY: How do you change that when we’ve reached a point where that sector of finance gets to more or less choose who’s president, they get to choose who runs the Fed, thy usually–it seems they get–and I’m very specifically talking about President Obama here–they get to choose his financial team, or he chooses them, because he knows where the money is?

JOHNSON: [crosstalk] the incentives are powerful, though I will give Obama credit: in the aftermath of his reelection, he did choose Janet Yellen, who has never been accused of being captured.

JAY: But that wasn’t his first choice, if we’re to understand–.

JOHNSON: I understand that.

JAY: Yeah. I mean, it was kind of pushed on him.

JOHNSON: Mhm. But she is in the position. She has been confirmed by the Congress. I think that’s a very hopeful sign that some of the broader interests of society are reflected in her focus on employment, rather than on what you might call catering to the financial sector, pure and simple.

JAY: But if this sector has mostly–maybe not completely, but mostly captured national politics and most state politics–

JOHNSON: And international. Yeah.

JAY: –and international and most municipal, how do you break the power of that? And in terms of INET, where are you at on this?

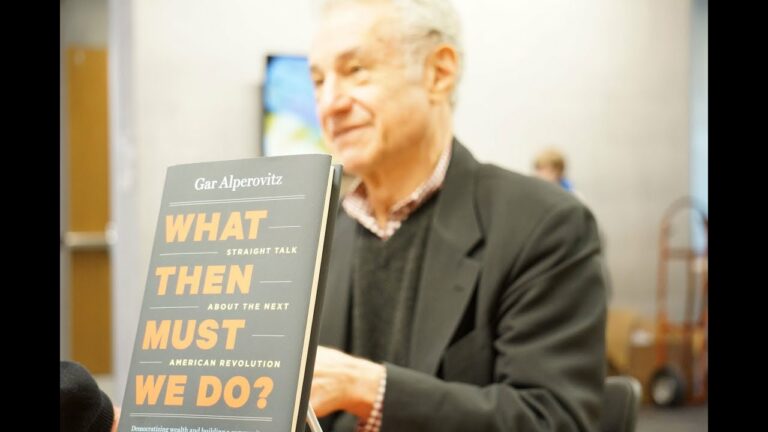

JOHNSON: Well, number one, we work on those fundamental presuppositions, the assumptions and the constructs of financial theory. And to show that things aren’t quite so Panglossian and beautiful, that finance can be stable or unstable, it can be destructive, it can be constructive, is trying to reopen the debate about what kind of architecture society needs. That’s held up in the intellectual halls of academia and theorists, etc.

I would say there’s evidence-based work going on. I just read a very interesting report about pay-to-play schemes with so-called alternative investments in pension funds done by some scholars at Stanford University, which show some very questionable returns for people who are investing in the state where they get the money, suggestive of political corruption. So there are scholars that are doing work that’s empirical. There’s discussion of the underlying financial theories. And that’s what we hope at INET will in 20 years percolate into what becomes conventional wisdom.

Another dimension at INET is to worry about money in politics, to see that markets and politics are not mutually exclusive in distinct domains, but they’re inseparably intertwined. And in that context, understanding the role of money in politics, the capture, just the weight in campaign fortune, is a precursor to calling for reform of the political process in ways that what you might call restore the value of the vote and diminish the political value of the dollar.

JAY: Okay. We’re going to pick up this story in the next segment of our interview. So please join us for our series of interviews with Rob Johnson on Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network.

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter

“Robert A. Johnson is the Executive Director of the Institute for New Economic Thinking and regularly contributes to NewDeal 2.0 with his “FinanceSeer Column.” He also formerly traded currency on Wall Street under George Soros.”