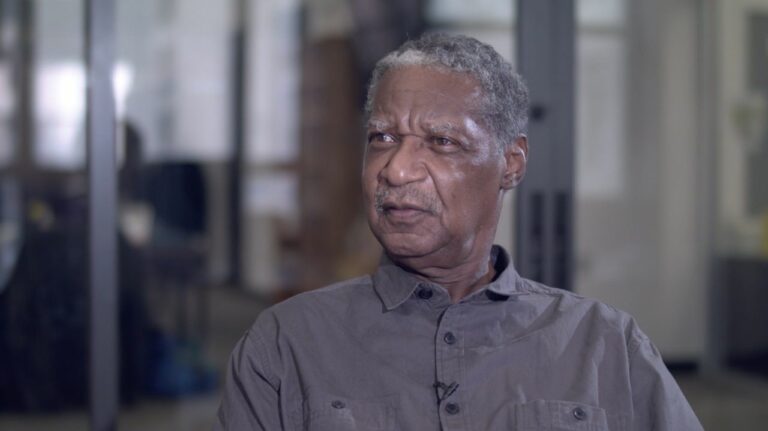

Mr. Shallal, owner of Busboys and Poets restaurants and candidate for DC mayor, tells Paul Jay that after coming to America as a child, the shocking death of MLK led him to discover how much race permeates everything.

This is an episode of Reality Asserts Itself, produced March 25, 2014.

STORY TRANSCRIPT

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay in Baltimore. And welcome to a new series of Reality Asserts Itself.

Our guest this week is a man who’s become a cultural icon in Washington, D.C. He runs a chain of restaurants called Busboys and Poets that’s become a hub for pretty well every progressive cultural thing that ever happens in D.C.–and, of course, not a lot of very progressive things happen in D.C. on Capitol Hill and the White House and such, so whenever something does happen, it usually gravitates to Busboys and Poets. He’s been an antiwar activist. He’s also gotten pretty wealthy, according to the newspapers, doing all this. He’s been called the–I think the rich socialist, one of his running opponents says.

And that’s another piece of this man’s story: Andy Shallal is also running for mayor of D.C. And I’m going to talk a little bit about how we’re going to handle that, but first I’m going to introduce Andy, who now joins us in the studio.

Hi, Andy.

ANDY SHALLAL, D.C. MAYORAL CANDIDATE: Hello, Paul.

JAY: So a little bit of bio here. Andy, as I said, is the owner of Busboys and Poets. It opened in 2005. It’s been a center, as I said, for politics, culture, and art in D.C. In 2003, he founded Iraqi Americans for Peaceful Alternatives in opposition to the invasion of Iraq and has been involved in the peace movement. He’s been very involved in developing things like Arab-Jewish dialog and such, and we’re going to find a lot more now.

So, as everybody knows who watches Reality Asserts Itself, the first part is usually personal. We ask our guest about why they think what they think, rather than what they think, which we’ll explore in the next segments or so.

So let’s start from the beginning. You’re born in Baghdad in 1958.

SHALLAL: In 1955.

JAY: Nineteen fifty-five.

SHALLAL: But thank you for making me three years younger. That’s good.

JAY: Alright. So you’re born in Baghdad, and you grew up there for the first ten years. So how much of that ten years is who you are?

SHALLAL: I think a lot happens the first ten years of life. You know, your values are shaped, the way you grow up, the interactions with family and how you see yourself within the family structure, and so on. I think that makes a big difference.

But I think a lot of what happened to me, at least, and what shaped my future thinking in politics happened here.

JAY: So as you grew up, your father is a diplomat?

SHALLAL: Yes, he was.

JAY: This is pre-Saddam.

SHALLAL: Yes, it certainly was.

JAY: So describe your memories.

SHALLAL: Well, pre- the second Saddam. You know, Saddam was there in the early ’60s as well. Then he left. He was spirited by the CIA to go to Cairo and lived there for a while. They paid for his apartment. And then he came back to Iraq.

JAY: The political atmosphere in your household, the kind of ideas, the discussion, I mean, I guess it’s pretty political, is it? Your father’s a diplomat. Tell us a bit about that.

SHALLAL: Yeah. I think, you know, politics is interesting in the Middle East, and certainly in my household my father was always very politically engaged. So political engagement in the Middle East sometimes means you listen to the radio a lot and you curse at the television set and you curse at the news. There’s not a lot of actual activism or being involved in politics, because that could cost you your life. So a lot of what I experienced was certainly my father, my family, my uncles, and others who were–just debates, constant debates about politics and, you know, conspiracies and ideas and things. You know. So it’s quite robust.

JAY: Now, you’re known now for your progressive politics, you know, which, you know, means a lot of things, but it also means, you know, sympathy for, fighting for social justice, economic justice, and so on. But I’m assuming your family is an elite family if your father’s a serious diplomat when you’re growing up. I mean, how conscious are you of the poverty of the–you know, the sort of class questions in Iraq as you grow up?

SHALLAL: I mean, we were middle-class, really. I mean, Iraq had a very strong middle class, and we were in the middle class. We weren’t wealthy by Iraq standards, or even by U.S. standards. So in that sense I grew up really in an average family.

JAY: What’s your understanding of the United States as you grew up? You know, there’s already one–the general atmosphere, you know, for good reason, is the United States one-sidedly supports Israel, and I guess much of the Arab world tries to get out of the United States what it can. It’s a love-hate with a lot of hate in that relationship.

SHALLAL: Well, the idea that you didn’t want to be on the wrong side of the United States, so that was kind of at least my impression. And certainly at the age of ten my impression of the United States was about culture, about television. It was cowboys and indians and things like that that we used to watch on television.

JAY: So you didn’t grow up in a hyper anti-U.S. kind of atmosphere.

SHALLAL: Oh, no. There is no hyper anti-U.S. I don’t know where that came from. I mean, there’s not a–maybe there are people that really dislike U.S. policies, but there’s not–.

JAY: No, I meant that.

SHALLAL: Yeah, there’s not that. Even back then it wasn’t–there was no hyper anything against the U.S. In fact, when my father found out we were coming to the United States because he was going to be a representative for the Arab League here, it was, like, the most exciting thing that’s ever happened. You know, everyone wanted to come to America. But America was far. You know, you had to travel quite a bit to get there. And it wasn’t accessible. It wasn’t–you know, people went to Europe that were able to, but they didn’t come to the United States. So having the opportunity to come to the United States was huge. People were, like, calling us. The phone wouldn’t stop ringing when my father found out that we were coming here, to tell us, this is so exciting, I can’t believe you’re going to, basically, Hollywood. And back then, you know, Jackie Onassis was considered, you know, the emblematic figure of American, you know, women and culture and style and all of that. It was kind of a big deal.

JAY: So your father is assigned to the United States, and around the age of ten you come to the United States. And then Saddam comes to power in a coup in Iraq and your father can’t go back.

SHALLAL: You know, lots of political turmoil that was going on at the time and lots of–. You know, my father was in the old government, and so the new government comes in. There’s usually a sweep. You know, when a new government comes, they do some cleansing. They round up the people that were with the old government, either lock them up or kill them. And so my father thought, maybe it’s a good idea for me just to hang out here for a while till things kind of settle down.

JAY: Did he lose his job? He’s no longer the representative for Iraq to the Arab League.

SHALLAL: Well, the Arab League was not an Iraqi thing. It was really out of Egypt. I mean, at that time, Nasser was the president of Egypt and the Arab League Center was in Cairo. And so Nasser was the one that–or he was the one that offered my father the job. So he really was not an Iraqi representative.

JAY: So he keeps his job.

JAY: Well, as you come to the United States and you grow up and a young man, you are a completely political being. You made your restaurants and cultural stuff, but you’re a political being. What shapes that for you?

SHALLAL: I think, you know, when we first came here when I was ten years old it was a very different country. You know, you watch America through the lens of the TV set back then.

JAY: What year are we in?

SHALLAL: This is 1966. So we came here. We came, we lived in Virginia&mdash–Arlington, Virginia–at the time. And being kind of a person with–you know, my race was ambiguous to most Americans. They didn’t know. Are you black? Are you white? There wasn’t a lot of brown in-betweens, you know, back then. It was: you were either black or you’re white.

And I remember going to middle school at that time and having to check off a box, I remember for the first time having to check off a box: are you black, white, or other? And it was very confusing, quite strange to be in a country where you had to pick a team, you know, of race. Race was a whole new construct in my mind, certainly. I wasn’t prepared for it. And so we’d leave the–.

JAY: So what did you check off?

SHALLAL: We’d leave it blank, because, you know, I didn’t think I was white and I didn’t think I was black, and no kid wants to be the “other”. That’s kind of a strange place to be.

JAY: But in fact that is what you were.

SHALLAL: Right. But the otheris a strange space for a young child. You want to fit in.

JAY: But whether you check the box off or not, do you start to internalize that I’m in that sphere called “other”?

SHALLAL: Oh, yeah. I’m definitely different than everybody else. And then, you know, the kids would be giggling and talking about, you know, what are you.

JAY: How was your English?

SHALLAL: Very weak. We didn’t speak English. And they would giggle. And the common question is: what are you? And I thought, only in America would you ask what are you. You know, I’m a human, you know, and trying to, you know, figure that out. And people would be always laughing and giggling about it.

And then 1968 came around, and Martin Luther King was assassinated, and we saw the streets go on fire. People were, like, burning buildings and all this, smoke smoldering in the distance. And suddenly you realize that race is serious business in this city, in this country, and you start understanding this overlay of race or underlay of race that covers almost everything that happens here. It’s part of the DNA of this country. Nothing moves without a racial component to it at some level or another.

So for us 1966 was a year where it was actually illegal for a black person and a white person to marry in the state of Virginia. It wasn’t until 1967 that that law was overturned.

And so, seeing how race played out–it determined everything–determined where you lived, who your friends were, where you sat in the cafeteria. It determined what kind of job you got. It was very interesting.

JAY: And what does it determine for you in terms of your identity, where you fit in all this? And what do you want to be? Because, you know, I would say, within the predominant culture, you would want to get to be as white as you could.

SHALLAL: Right. Right. So trying to figure it out, of course, I wasn’t accepted in the white group. You know. So, obviously, you want to go to the dominant group, but we were not accepted. Certainly wasn’t accepted in the black group. And so we stayed in this sort of limbo state, really, for a long time.

And it’s funny, because my brother looks more white than I do. And so he did not have the same experiences I had. I have two sisters also. One of them looks African-American. She could pass for a light-skinned African American easily. The other one looks like she’s Italian or French, you know, complete European-looking. And so when I talk to my sisters, the darker sister and I have much more in common of how we interpreted race as my older siblings, who were lighter and had a whole different experience.

JAY: And how has that affected the way you look at things politically?

SHALLAL: I think, you know, then, moving fast-forward, living in Washington, D.C., understanding the nuance of race, you know, how race really determined so much of what’s going on. I know it wasn’t 1968 anymore, but even years later, decades later, race still plays a very significant role not only in Washington, D.C., but certainly in the United States as well. You know, we elected a black president, and we are far from being post-racial. So people understand race is very, very significant in what happens.

JAY: So what event is the sort of triggering event for you that really engages you or–?

SHALLAL: I think the assassination of Martin Luther King was very significant, the fact that people were so angry. I didn’t know where that anger came from. You know, I learned about American history at some level, but–you know, and also your school and the school environment.

And then, of course, 1967 was another important year, when the Six-Day War happened between the Arabs and the Israelis, and that also colored my perspective of how America plays a role in that conflict.

JAY: Specifically?

SHALLAL: Well, having a teacher that was in the school that my brother and I both went to, the middle school, where the teacher was a Zionist, and she was speaking about how the Arabs were trying to push Israel into the sea, and how–you know, thank goodness that, you know, Israel was able to counteract that huge, huge push, and really a very strong pro-Israeli perspective of history. She hung a picture of Moshe Dayan, I remember, in the classroom and pointed to him as a hero.

And, you know, for me, of course, being an Arab, that was a whole different story I was getting at home. And I remember, you know, during the 1967 war, my father had this little Zenith shortwave radio that had an antenna that went all the way to the ceiling so he could hear the news from one part of the world to the other. So he would pick up the early news from London, and then move forward as the sun came up, you know, to this side of the ocean, and really hearing the news during the ’67 war, the Six-Day War. And I remember every day the news would become narrower and narrower, ’cause he was always looking for that sign of victory that the Arabs were going to have. And every time he would listen to a certain news station, you know, they would tip it to the other side, he would stop listening to that news station, and continue to search for that one station that’s going to give him the news that he wants to hear. And so–you know, we didn’t have The Real News then.

JAY: When it comes to checking off the “other” box, as we said, check it or not, you’re the “other” on a racial basis. When it comes to 1967, you’re the otheragain, because the whole official narrative is pro-Israeli in the United States. So to be in a family where you’re hearing the other side, whereas not just school, everywhere you go, I assume, you’re hearing a pro-Israeli position.

SHALLAL: Yes.

JAY: So whether you’re checking “other” or not, racially you’re part of the other. But now you’re the other again. Nineteen sixty-seven, the whole narrative is pro-Israeli, and you’re coming from an Arab family, and you’re hearing, you know, the other side, but you’re not hearing that outside the door, outside the home. So how does that affect–you know, as an immigrant family, usually pretty quickly the kids buy into Americanism. But for you it would have been not so simple.

SHALLAL: I think you go through that process, you go through the process of trying to pretend you’re something else, trying to fit in in whatever environment you’re in. You learn to be a chameleon, in a sense, you know, trying to figure out where you are and trying to cause as less friction for yourself as possible. So, obviously, there’s going to be some of that processing that goes through at the beginning.

And then after a while you start figuring that you need to have your identity back. I mean, it’s really important to do that. And, you know, then you start to assert yourself, and you start–. You know, when we started college, we started getting involved in the International Student Association or people that really were more in line with our own experiences, and they were the internationals, they were the new immigrants, they were people that are moving in this country and themselves are trying to find their identity. And so we fit in with that group of people, I think, much more.

JAY: So first Iraq war, you become active in opposing it.

SHALLAL: Yes.

JAY: Now, you’re opposing an invasion of Saddam’s Iraq. You have relatives who were killed by Saddam.

SHALLAL: Right.

JAY: Is there any ambiguity or mixed feelings for–I mean, is a part of you might not mind seeing a bomb fall on Saddam’s head?

SHALLAL: Well, I think by that time we were Americans. You know, we have accepted the fact that we are Americans at that point.

JAY: What year are we in, again?

SHALLAL: This is now 1990. This is the first Gulf War, when–Papa Bush was in charge at that time. And so when that invasion was happening, it was really about America at that point; really it wasn’t so much about Iraq. I’m an antiwar activist. So for me war was not a solution to world problems, that there’s other ways we can resolve things that are less destructive and less unpredictable. And so my interest was really to get involved in kind of holding the United States to a different standard and saying, hey, we are a superpower; we need to use our power not to destroy, but really to build and fix and create alliances. And to me a war was not the way to go.

I think I started to sort of think, you know what, I’m an American now, that if I’m going to swear allegiance to a flag, I want to make sure that flag lives up to its values. And so I really got much more involved in American politics and understanding of politics, understanding American history, what the role of citizenry is in the political process. So I got very engaged in that.

So when 1990 happened and the invasion of Iraq was taking place then, I was very involved. I was out in the street, I was demonstrating, I was involved in local politics, in national politics. I started working on the Jerry Brown campaign at that time a couple of years later when he ran for president. I became a delegate at the National Convention, and got very, very involved in local and national politics at that point.

JAY: Okay. In the next segment of our interview we’re going to carry on with Andy, we’re going to do a little more biography, ’cause I try to do all this in the first segment, but he’s lived too much life–I couldn’t do it in one segment. So in segment two we’re going to talk a little bit more biography, and then we’re–get into some of the current issues that he’s grappling with as he runs for mayor of D.C.

Please join us for the next segment of Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network.