Despite being (mis)characterized by the IMF as a free-market “success story,” South Korea’s development model involved state planning and import controls for decades prior to the 1997 East Asia debt crisis. Economist Martin Hart-Landsberg, Professor Emeritus at Lewis and Clark College in Portland, explains how capitalist globalization materialized and morphed in East Asia, often to the detriment of its worker population. With Trump’s inauguration nearing, Hart-Landsberg sheds light on why contemporary U.S.-China hawks view China as a threat rather than a technological competitor.

FDR’s Wartime Strategies Can Power a Just Transition Now – Martin Hart-Landsberg Pt. 2/2

Talia Baroncelli

You’re watching theAnalysis.news, and I’m Talia Baroncelli. Today, I’ll be speaking with economist Martin Hart-Landsberg. We’ll be discussing inequality and capitalist globalization in East Asia.

If you enjoy the work that we do and would like to support us, you can go to our website, theAnalysis.news. You can hit the donate button at the top right corner of the screen. Make sure you get onto our mailing list; that way, we can send all of our new content straight to your inbox. Make sure you like and subscribe to our YouTube channel and hit the bell so you get notifications every time we publish new content. You can also listen to us on podcast streaming services such as Apple or Spotify. All right, let’s get into it with Martin Hart-Landsberg.

Joining me now is Martin Hart-Landsberg. He is a Professor Emeritus of Economics at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon. He’s the author of several books, including Capitalist Globalization: Consequences, Resistance, and Alternatives, as well as a few books on Korea. One of them is called Korea: Division, Reunification, and U.S. Foreign Policy. Marty, it’s really great to have you here today. Thank you for joining.

Martin Hart-Landsberg

Oh, it’s my pleasure. Thanks for the invitation.

Talia Baroncelli

I wanted to speak to you about capitalist globalization, given that you’ve done a lot of research in China, Japan, and Korea. If we look at the global capitalist system, we see a lot of countries, particularly in the Global South, experiencing unsustainable debt. The IMF, the International Monetary Fund, as well as the World Bank continue to argue that neoliberal policies present a solution to these economic crises, and they continue to assert that neoliberal policies, as well as structural adjustment programs, be implemented. Do you really see neoliberalism as alleviating poverty, or do these policies simply continue to exacerbate a lot of the existing inequalities in the global system?

Martin Hart-Landsberg

Well, I would say it’s the latter. To put the debt crisis that you mentioned in some kind of perspective, in the last decade, even according to the World Bank, there has been no reduction in global poverty. In fact, the World Bank, in its most recent report, said that without drastic action, it could take more than a century to eliminate poverty as it is defined for nearly half the world. You have to understand that we’re entering into a debt crisis, and the last decade has essentially been a lost decade.

You know, poverty is bad when the international agencies come up with multiple measures of it. What they do is they take a bundle of goods in a country, say, haircuts, a shirt, and then they take the same bundle of goods in the United States, and they compare the prices, and they make an exchange rate so that there should be equivalents. The lowest level of poverty that the international agencies use is $2.15 a day, which is about $785 a year. If you make above that, you’re not considered poor, which is a little staggering. About 10% of the world is below that level. Then they have another level, which is $6.85 a day, compared to U.S. living standards, $2,500 a year, and about 45% of the world’s population is below that.

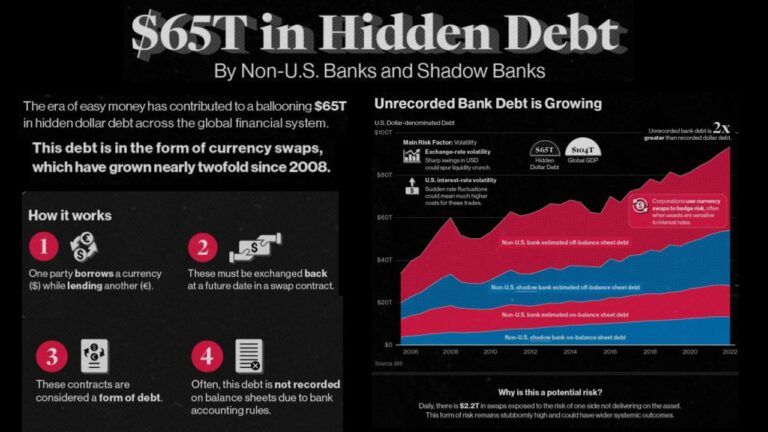

For the last 10 years there has been no improvement and now a debt crisis. What does that mean? Over the last 10 or 12 years, ever since the global financial crisis, the exports of these countries, which have largely been shaped by this global system and limited, have not earned very much. If countries follow the free market, people are free to import as they want. As they try and import, if the imports grow faster than the exports, they have to find a way to pay for it, and that’s usually been borrowing. Over the years, they’ve been borrowing more and more money to cover this imbalance, but because they don’t want to get too big into debt, they keep their growth slow, so people are poor, and they don’t import so much.

Over the last several years, what’s happened, particularly with COVID, is the price of energy and food went way up, so imports went way up, and interest rates went way up. Almost all the loans that these countries took out are on flexible rates. Even the IMF, when it loans to countries, uses a flexible rate. Even China, which is a major lender to the Global South, 45% of their loans are flexible rates. All of a sudden now, the amount that these countries have to pay is enormous to them.

Here are extreme examples. Mozambique and Angola now have debt service costs that are equal to 20% of their GDP. Almost half the countries of Africa have to pay in debt more than they spend on health care and education combined. Latin America– Bolivia is an extreme case– they have reserves of about $1.5 billion when they used to have reserves of $15 billion.

What happens when you suddenly have a debt crisis? How do you solve a debt crisis? Well, you either borrow more to pay, and no one wants to lend them, or you have to make your citizenry poorer. How does that work? Well, you don’t want people to buy food if you subsidize it. So you end the subsidies, they can’t afford food, you reduce your imports. If they’re using health care and you have to import things for health care, you stop letting them do that. Then their health care goes down, but you don’t have to import it. You make people poor, they buy less, and you essentially bring the imports down. That’s why the World Bank says, “Going forward, it’s going to be a century to try and do anything because these countries are now going to be going into reverse.”

Then we get to the question of, well, why are they in this situation? Why is it that following a free market strategy of reducing consumer and business activity to solve the debt crisis? Why are they in that situation? Here, I think models matter, and South Korea is the country I want to use.

South Korea was a very poor country in 1960. By the end of the ’80s, into the ’90s, it was widely considered a success story. International agencies go around, and they say, “Oh, you’re doing so poor. You need to do what South Korea does. South Korea is a free market miracle.”

For example, I was in South Korea in the early ’90s after the Soviet Union ended, and the IMF had a tour group of people from some of the Eastern European countries, but some from Africa, some from Latin America, and they were there to learn about the South Korean miracle. They were told by Korean professors, “Oh, they welcomed foreign investment. They were open to free trade. The government stayed out of the economy, and that’s how they succeeded,” which is not the case. I want to go back to that in a second.

I visited this professor, and I said, “I hear you’re telling them X, Y, and Z. That’s not my understanding.” He said, “No, it’s not mine either, but the IMF wants this story out, so it puts pressure on the President of the University who tells me, and I do this.” The same thing happened in South Africa when the ANC took office. They said, “You need to be like Korea.”

What is the Korean experience? Well, when Park Chung-hee took over with a military takeover in 1961, he created an economic planning bureau. That bureau had the ability to control foreign direct investment and foreign borrowing. What did that mean? Not a single foreign direct investment came into Korea that included a takeover of a domestic company. Not a single foreign direct investment came into Korea to set up the production of a domestic consumption good. The only foreign investment that was allowed was investment that would support Korean economic activity. The government took over the entire banking system—same thing in Taiwan.

One question you have to say to yourself is, how did Korea and Taiwan, for example, have the ability to take over the entire banking system to limit things like this? In places like Guatemala and other countries, if governments even try liberal land reform, they get threats from the U.S., but the U.S. wanted these countries to succeed, so it allowed them to do this.

For further examples, Korea and Taiwan had limits on imports. When you say to yourself, how did Korea get such an incredible industry to produce consumer electronics? Because they limited– there was never Japanese consumer electronics sold in South Korea. They had limits on imports. They controlled them through a variety of complex ways. Every company had to belong to a producer association. You couldn’t produce unless the government let you in. Why is it that Hyundai produces cars and Samsung doesn’t? Because the Korean Ministry of Trade and Industry said to Samsung, “We don’t see your contribution to the auto industry, so we don’t allow you in.”

Maybe just as a last example, to get a sense of what planning means, when Korea controls its banking system, it can pump money into the industries it wants to grow. For example, it wanted to start having a tanker industry and shipping industry, but it didn’t have a company that produced it. It went to Hyundai and said, “We’re just going to give you the money to start shipbuilding.” How does Hyundai do that? Well, Hyundai controls an auto industry, a cement industry, and a construction industry. It pulls people out and moves them into shipbuilding. They produce ships. At first, there were no demands, so the government said, “All oil coming to Korea has to be on Hyundai ships,” and Korea now has an incredible shipbuilding industry. So, very tightly planned, controlling who gets money, what the imports are, and what foreign investment– nothing like what the IMF is saying.

Now, one of the problems is, of course, that this was a dictatorship. A tremendous repression of workers which added to that. One of the things for me when I would visit Korea in the late ’80s and early ’90s was that workers had a sense that state planning was what elevated them, but what would it mean to democratize the state planning system? How do you ensure that instead of an export-driven economy, which pits workers against each other, you can create an economy that’s more domestically centered? That produces goods and services that are responsive to people. There were really rich discussions and debates that got short-circuited by repression against the Left in South Korea.

The point is that the IMF and World Bank continue to put these things forward, that the free market will solve countries’ development problems when the experiences of successful countries like Korea, Taiwan, and even the People’s Republic of China show that it’s planning. I’m not trying to romanticize it because, in many cases, these are governments that are also repressing labor, but these are techniques and strategies that you need to restructure economies. The problem is that the developed capitalist countries are not very eager to see other countries follow suit.

In fact, why is the Korean economy struggling now? Because Japan and the United States didn’t like the competition. They pursued strategies that ended up leading to a debt crisis for Korea and the unraveling of its planning. There’s a lot going on. The important thing to say is that the successes in economic development have come from planning. Most economists don’t learn about these things. How does planning work? Under what conditions? What an international agency should be doing is strengthening countries’ capacities to plan rather than telling people that planning doesn’t work and pursuing loans and advice that undermines their ability to plan.

Talia Baroncelli

I do want to ask you a bit more about this unraveling in the South Korean context, but could you just clarify one thing? What you’re describing to me sounds like a protectionist economy, not the creation of free-market economic zones or the implementation of free-market ideology. Is this a false dichotomy, or was this really free-market ideology that was being put into practice?

Martin Hart-Landsberg

Yeah, it’s the exact opposite of free-market economics. In fact, Park Chung-hee, who took over with a military dictatorship, his work in the military had been studying North Korea and its planned economy. He had been a soldier and an officer in the Japanese military when Japan colonized Korea, which was a planning experience. He was not a fan of planning. The difference is that Korea exported, but it continually used its protection and its domestic control to create the ability to keep upgrading and export higher-quality goods. It wasn’t only focused on domestic or only focused on global, but it created an overall plan. If South Korea said, “We want to be an auto producer,” the government set up its own steel industry to provide cars, and it restricted– you could not buy a Japanese car in South Korea. You could sell cars in Korea, become more efficient, and then export them. There was a sense of both, of working to integrate them.

What happened over time, and this gets back to understanding how the global economy operates. People may remember in the 1980s, the U.S. was running very big trade deficits, and particularly Japan was seen as the problem. Whenever the U.S. runs into a threat, it seeks to use its strength to stop that threat. It said to Japan and Germany, in fact, because they were running trade deficits with Germany, “You need to take actions to solve our balance of payments problem.” The agreed action was for Germany and Japan to raise the value of their currency so their goods would become more expensive to U.S. consumers.

What happened then is that the Koreans didn’t change their currency, and they began increasing their sales to the U.S. The Koreans began replacing the Japanese by selling consumer electronics, cars, and other things. Well, the Japanese said, “Unacceptable,” so they cut off the supply of critical technologies to Korean companies. The U.S. said, “Unacceptable,” so they forced Korea to raise the value of their currency. Gradually, Korea’s export offensive unraveled, and they had to borrow more and more money.

Then, in the late 1990s, there was a financial crisis when investors said, “Wait, these countries like Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Korea are running bigger and bigger trade deficits, and who knows if they can pay back debts?” They pulled out their money, and these economies collapsed. The IMF came into South Korea and said, “Take apart your planning system. You have to sell off your banks. You can’t control imports. You have to let more foreign investment in.” For the big companies that had been created by the planning system, they said, “Great. That gives us more freedom to go abroad because we were always carefully controlled. We can now make money in different industries. We don’t want the planning system. Now we can also, through globalization,” as Korean companies have done, “make more money producing in other places.”

As a result, Korea, over the last decade, two decades, has had very slow growth growing inequality and economic problems. The issue is not just, is there a perfect strategy? It’s a global capitalist system where countries like the U.S., Japan, and the European Union are always on the alert to see when there are rivals. There may be historical moments when they’ll support a country’s rise, allowing Taiwan or Korea to control its economy, but if it gets too threatening, they take steps to undermine it.

Talia Baroncelli

Would you say that Korea fell in line after that? Because now we see stagnation in the Korean economy. There’s not a very strong labor movement in Korea, and there are a host of other problems there. We don’t need to speak about the problems with the current president who was impeached, but that is illustrative of a lot of the tensions within Korean society. Would you say that the country fell in line and started to not push back against American hegemony? Is that also why Samsung is still such a huge exporter, or how do you account for those factors?

Martin Hart-Landsberg

State planning in Korea built up these very large, powerful companies like Hyundai and Samsung, but state planning could keep them in check. You make a lot of money, but you’ll do it in the ways that we say. There’s a lot of corruption, but it’s through production and investment, as the state planners wanted.

What happened after the financial crisis in the late 1990s is that the IMF said, “These restrictions have to be removed.” For the big companies, that was good. It wasn’t ideal for them. They rather that it wasn’t a crisis, but it was a silver lining. They have taken advantage of that. As a consequence, their power is unchecked.

Korea has become a much more typical capitalist economy that’s been globalized. I think what’s happened also is that the labor movement is a lot weaker. When you have companies that are globalizing, being militant isn’t always a good answer. You go on strike, and they say, “Great, we’re moving to Vietnam. We’re moving to China. We’re setting up production in the United States.” I think the labor movement in South Korea is really struggling to say, “We need a new kind of economy, but what does that look like, and how do we approach that?” I think they’ve lost a lot of the insights and strengths that they had in the past. I think right now, the powers that be in Korea have embraced this globalization because their dominant companies are free to make money.

Talia Baroncelli

Right. They’re also a signatory to the World Trade Organization. There’s a lot that they can’t really change or adjust in favor of workers because they’ve signed onto these really brutal contracts.

Martin Hart-Landsberg

To give a real sense of how the IMF, the World Bank, the U.S.– I don’t know how much they believe– but they really play games in talking about the free market, globalization, and how it helps, is what happened in Western Europe after World War II. When the war ended, most of Western Europe had been devastated by the war, and the U.S. said, “Open up your economies, be a free market.” Western Europe said, “If we do that, we’re going to pull in a lot of imports. We can’t export much because our industries are weak, and we’re going to run into a debt problem. We’re going to have to then repress our economy. We have strong Lefts in France, in Italy, in other places, and who knows what will happen. We’re going to refuse.”

During the Depression and the War, a set of controls had developed, and European capital and its state had capacities, they resisted the U.S. What the U.S. ended up doing was negotiating something called the European Payments Union. Beginning in 1950, the U.S. allowed the Western European countries to essentially maintain a closed collective system where, for example, if a Swedish farmer wanted to buy a German tractor and there was no foreign exchange, they would go to the Swedish Central Bank and pay in Kroner. The German Central Bank would then pay the German tractor producer in Deutsche Marks. The central banks would keep track of all this. At the end of the month, they would total up their relative balances in their inter-European trade and report them to the Bank of International Settlements, who would keep a record.

At the risk of oversimplifying, they would say, “Well, if you’re a country that ran a bit of a deficit, we’ll just give you free credit so you don’t have to repress your economy. If you’re in a surplus situation, we’ll give you some of the foreign exchange you would have earned, but not all of it.” We keep controls on, so you can’t just go in there and say, “Here’s my currency. Give me dollars so I can buy from the U.S.” It’s all limited. You can’t just buy any goods. There are quotas and restrictions.

The European Union existed in this program of a regional planned economy, a regional economy from ’50 to 1958. It wasn’t until 1958 that they made their currencies convertible and that they dropped their controls on imports. Well, if developed capitalist countries need eight years of planning and control over imports and control over exports to feel secure, why would we expect countries who have undergone the exploitation that most of the countries in the Global South have to open up and actually succeed? There’s time and time again, when big capital knows that development is important, they have created space for planning for powerful states.

Talia Baroncelli

Can you speak about how the conditions in East Asian countries such as Japan, China, and Korea have changed over the past few decades? Now, we see that a lot of multinational corporations have been set up in China, for example. I know a lot of your work has dealt with China in particular and how there’s been a huge U.S.-China trade deficit over the years. China has, over the past decade or so, also imported goods from other parts of East Asia to then assemble them in China and then export those final, I don’t know what the term is, produced goods after they’ve reassembled them themselves.

Martin Hart-Landsberg

The final [inaudible 00:24:45].

Talia Baroncelli

Yeah, exactly. How have those dynamics changed as well in terms of how China, Vietnam, Korea, and countries in East Asia interact with one another and what the implications are for Chinese workers?

Martin Hart-Landsberg

Well, there’s a lot there. I guess one thing to say is that the way global capitalism is operated has made almost every country export-oriented. That’s a real problem because it ends up pitting workers against each other and essentially ignoring what workers in different countries need for their own consumption. Everybody’s competing to produce the highest value goods, the luxury goods, the consumer goods for the richest markets. There’s no sense of balance. Everybody can’t produce those unless they end up fighting among each other, workers getting pitted against each other, and conditions deteriorating for workers.

But to go back, when I mentioned the U.S. demanding that Japan and Germany raise their currency value, the response in Japan was, “Well, we’re going to hold back on selling imports to Korea, but we need to do something.” Their big companies began to shift, first to Thailand, then to Malaysia, and then, when China opened up, to China. One of the reasons that Japan has had decades of stagnation is because Japanese companies are no longer investing primarily in Japan. They have globalized. Once Japan started to move to China and producing with lower Chinese wages, Korean companies had to say, “Well, how can we outcompete Japan producing in Thailand, Malaysia, and China, exporting to the U.S. and the EU with our higher wages? Well, we need to start moving.” They began to move to China as a way to compete and also sometimes to sell parts, components, and technology to the Japanese companies that moved.

What you begin to get is these dominant countries maintaining some capacities in their home country but increasingly moving production to China. The same thing happened in Taiwan. By the mid-’90s, 50% of Taiwanese’s foreign investment was going to China, all their semiconductors, for example. It’s not just only to China because sometimes parts and components could be produced in Malaysia and Indonesia. Big capital is just looking to say, “Where can we get the best deal? Where can we put production in?”

What happened is in the ’80s, and the early ’90s, a lot of countries had companies that produced full-finished products and exported them. In East Asia, their countries become subject to these global processes, and they become essentially integrated together. So goods that are produced in China, assembled in China, may come from some parts in South Korea, some parts in Japan, some parts in Malaysia, Taiwan, but where does the final good go? Mostly to the U.S., the European Union, or maybe Japan.

East Asia became part of a globalized production network. Most of the production was organized by these global corporations. Many of them came from the United States, increasingly coming from Germany as well. Those operations mean that China became the world’s workshop. That’s where most production was.

One of the challenges for the West is that— although in my opinion, China has become a capitalist country, I know that’s a debatable position, but its manufacturing sector is largely private— China’s state capacities, which remain significant, have meant that they were able to take advantage of some of this and build up their own state institutions, their own state industries, and are now not just a simple assembler of basic goods and services, but direct competitors to Japan, the United States, and Germany.

China is a very big country. I mean, it’s resources— it wasn’t a typical third-world country. Even when China began its marketization in the late ’70s and early ’80s, people often said, “Oh, under Mao, China was this failure,” it was far from that. It had an educated working class. It had a healthy working class. It was building supercomputers, it had missiles, and heavy ocean-going vessels. It had capacities to draw on and to use these investments. Now, It’s the number one market for all of East Asia because they’re selling their parts and components, but it’s become a much more independent producer. In that sense, I think the U.S., Japan, and Germany are now feeling the pressure of the export orientation. China, like all these countries, has become a major exporter. Its growth is not from domestic consumption, but it’s largely export-oriented. The problem is globalization keeps reinforcing this export activity to the detriment of workers in all these countries.

Talia Baroncelli

It’s becoming more expert-oriented, but does that mean that the manufacturing base itself has expanded? Are there more manufacturing jobs in China now, or is that not the case?

Martin Hart-Landsberg

Total manufacturing employment in China is going down. It’s becoming more capital-intensive, and the economy has changed. What the data seems to suggest is that more Chinese companies are producing the parts and components that they use to import from other countries. But in the core areas of technology, the semiconductors, the operating systems for phones and computers, they’re still dependent on imports. They haven’t reached the same level that a lot of the Western companies have.

China has succeeded in localizing a lot of production. As a consequence, they’re not depending on imports from Thailand, Malaysia, and other countries as much, and that’s affecting their growth. The overall manufacturing employment within China has been going down, and unemployment in China is actually going up. One of the things where the Chinese mask this is in China, where you’re born, you have a household registration system. If you move from a rural area to an urban area, you maintain your household registration system in the rural area.

Nowadays, in China, I’d say two-thirds of the manufacturing workforce are internal migrants, but because they don’t have a household registration system in the urban area where they live, they are not counted as unemployed when they lose their jobs. They don’t have access to public services because they’re not citizens. They can’t send their kids, even if they have kids there, to public schools for free. They can’t access subsidized health care, but it also means that their lower wages are not counted when the Chinese government lists what are the average wages and what’s the average unemployment. They only count workers with a registration system in the urban area.

One of the reasons that consumption keeps falling as a percent of production in China is this downward pressure on wages in China. That’s led Chinese companies to start to move from the old areas where they originally produced to the hinterlands of China, where the wages are even cheaper. That’s not only Chinese companies, but, for example, Foxconn, which is a Taiwanese company that left Taiwan to go to the People’s Republic of China. Taiwan is now struggling economically because so many of its companies have left. Companies like Foxconn are then moving from the populous areas of China to other places in China where they can get cheaper wages. The whole globalization process is such that, yes, China has localized more, but the context isn’t necessarily so advantageous for Chinese workers.

Talia Baroncelli

You were speaking about the pressures that have been placed on Chinese workers and have led to wage stagnation. Wage stagnation is obviously a huge issue in the North American context. If you look at real wages, so when you take inflation into account, wages have not really increased all that much for the average American worker. Over the past 50 years or so there’s been widespread wage stagnation.

You also pointed out in another article how the consumption of Chinese goods by the American worker has largely been driven by bubbles in various sectors of the American economy. If you look at the housing market, for example, the housing bubble of 2007 is what largely drove a lot of that consumption. Then, of course, we saw when that bubble burst what financial catastrophe it actually led to.

I think this is a moment for us to segue into a foreign policy issue and look at U.S.-China foreign policy. Biden just gave his last foreign policy speech. He said that China will never be able to surpass the United States and that the United States is in a much better position after four years of Biden’s presidency to face China as a perceived threat. I wanted to ask you why do you think the China hawks perceive China as a threat rather than just simply a competitor?

Martin Hart-Landsberg

Well, it’s a good question. I think almost any time the U.S. has faced a very serious economic competitor, they viewed them as a threat. I use the example of Japan when they forced the Japanese to raise their currency. They actually said, “Not only raise your currency, but we want you to control how many semiconductors you send and how many cars.” They took pretty strong action. They were able to do that because they also still had military dominance and political dominance, and they were able to force Japan to do what they wanted.

When Korea had its crisis in the late ’90s, the U.S. was actually pivotal in forcing and pressing the IMF to demand that Korea unravel its planning. They saw it as an economic competitor and a threat, but they also had the political and military overarching power to force Korea to accept that. The problem with the case of the Chinese economy is that it’s far bigger than Korea and Japan, and U.S. capital has been very invested in China. Our car companies have bigger markets in China than at home. Apple relies on China for huge amounts of production. We import, I’d say, almost all of our consumer electronics in one way or the other come from China, wherein Japan and Korea, U.S. capital, was less integrated into those. It was easier to just say, “You’re an economic competitor. We demand you do X and Y.” The U.S. has a much more difficult time dealing with China as a competitor because it’s very diverse now, and U.S. capital is so interwound with a lot of production there that how do you handle it?

Forty percent of China’s exports to the U.S. are parts and components that go into U.S. production. Fifty to sixty percent of its imports are electronics goods, usually produced in concert with U.S. companies. I think for the U.S. state to try and deal with China, they turn it into not just a competitor but a threat, a national security threat, because they need an extra level of impetus to try and force companies to do things they don’t want to do. Where with Japan and Korea, it was pretty easy to mobilize the U.S. capitalist class and say, “Yeah, these are competitors. Let’s force them to do things that will weaken them.” China is different. The U.S. can’t exert, at least at this point, military control or political control, and the U.S. capitalist class has more mixed feelings.

For the U.S. elite, labeling the China situation not just as an economic competitor but threats a national security threat provides a different way for them to try and get at China and to try and push it in the ways they want, to this point, with only minimum success, really.

I would also say, one way you can see this, there’s a lot of attention in the media that the U.S. is saying, “Well, the key to beating China militarily and economically is semiconductors, it’s AI, it’s all these things. We want to deny China the ability to get access to these.” The U.S. has passed laws saying U.S. companies or any companies based in the U.S. can’t sell China machinery to make advanced semiconductors, but it turns out that that law is very limited. Those same companies who operate in the U.S. have foreign affiliates, and they’re still selling those things to China. The U.S. state has not had the ability or the willingness to try and close that loophole. I think this is where the complex situation is for the U.S. and why the U.S. government and China hawks see China as such a threat, not just a competitor.

Talia Baroncelli

Yeah, the legal landscape there plays into it because not all of these laws are enforceable in other legal contexts. I guess if it’s a subsidiary company of a U.S. company operating in China, then they’re not bound by the same laws as they would be in the United States. You can’t really enforce that [inaudible 00:39:44].

Martin Hart-Landsberg

The U.S. is doing that with Cuba. They’ve said, “We have an embargo on Cuba, and to companies operating outside the U.S., if you use parts and components or technology from us, you can’t sell those goods to Cuba.” Now, maybe I don’t know what the law is, maybe it’s just the political pressure, but again, it’s an example that what makes China so threatening to the U.S. is that we’re talking big companies and big money and integrated production, the globalization that makes these companies more resistant to this, which ups the threat warning for U.S. planners.

Talia Baroncelli

You’ve been watching part one of my conversation with economist Martin Hart-Landsberg. In part two, we’ll be speaking about the history of World War II, the mobilization that was enabled by planning under the FDR government, and how the Left can actually learn lessons from that particular experience to enable a just transition. See you next time.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | TuneIn | Deezer | RSS

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter

Martin Hart-Landsberg is Professor Emeritus of Economics at Lewis & Clark College, Portland, Oregon. His areas of teaching and research include political economy, economic development, international economics, and the political economy of East Asia.

He is the author of seven books on issues related to globalization and the political economy of East Asia, with a focus on China, Japan, and Korea; his work has been translated into Hindi, Japanese, Korean, Mandarin, Spanish, Turkish, and Norwegian. He has also published numerous articles in journals such as Monthly Review, Critical Asian Studies, Journal of Contemporary Asia, Review of Radical Political Economics, Against the Current, and Historical Materialism.

He is a member of the Board of Directors of the Korea Policy Institute and the steering committee of the Alliance of Scholars Concerned About Korea, and has served as consultant for the Korea program of the American Friends Service Committee. He is also the chair of Portland Rising, a committee of Portland Jobs With Justice, and chair of the Oregon chapter of the National Writers Union.