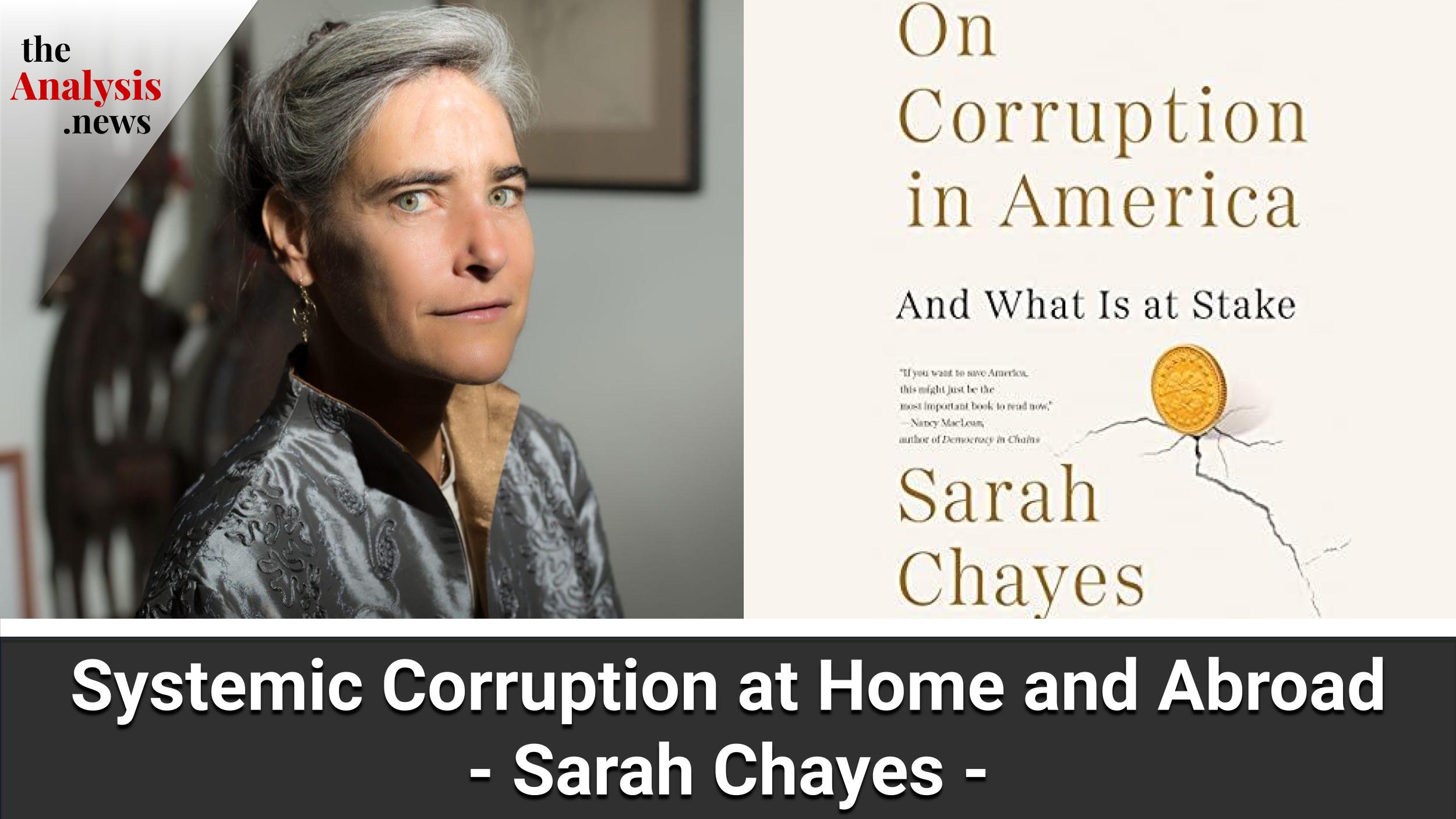

Author of the book “On Corruption in America: And What is at Stake” and former NPR correspondent Sarah Chayes discusses embedded corruption networks in Afghanistan, particularly under U.S. and allied occupation, and other countries plagued by endemic corruption. She argues that the very institutions— primarily Western— seeking to tackle corruption in these countries end up propping up corrupt financial and military institutions by supporting networks of elite capital interests and a conglomeration of private contractors.

Sarah Chayes photo credit: Kaveh Sardari.

Talia Baroncelli

Hi, I’m Talia Baroncelli, and you’re watching theAnalysis.news. Joining me in a bit is former NPR correspondent, Sarah Chayes, to speak about her new book On Corruption in America: And What Is at Stake.

Before we get to it, if you’d like to make a small donation to the show, you can do so by going to our website, theAnalysis.news, and hitting the donate button at the top right corner of the screen. Make sure you’re also on our mailing list. That way, you’re always up to date if there’s a new episode. Like and subscribe to our show wherever you listen to the podcast, be it on YouTube, Spotify, or Apple. We’ll see you in a bit with Sarah Chayes.

Joining me now is Sarah Chayes. She’s a former NPR correspondent and author of numerous books, including On Corruption in America: And What Is at Stake, which is also known as Everybody Knows, just in case you’re buying the book outside of North America. In Europe, it has a different title, so just pointing that out. Sarah has also been a special advisor to the U.S. military in Afghanistan and has served as an advisor to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Thank you very much for joining me today, Sarah.

Sarah Chayes

Thanks for having me, Talia.

Talia Baroncelli

Just a quick side note to our viewers and listeners: you’ll be able to hear Sarah today, but you won’t be able to see her. Nevertheless, we’re going to have a great discussion. I wanted to start off, Sarah, by pointing to the experience you’ve had in numerous countries abroad, such as Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Nigeria, and several other countries. In your book, you speak about the conversations you’ve had with people on the ground and how they point to the networks of corruption that exist in those societies and how the consolidation of elite structures and elite corruption mirror networks in the United States. I was wondering what prompted you to draw this conclusion in the first place?

Sarah Chayes

First was the issue of patterns. I actually, in the very beginning, came to corruption through living and working in Afghanistan, where, in fact, it was Afghans who brought the matter to me. It was not me coming in with some Western set of standards and imposing them on the local population. I thought I was doing development work, and all Afghans wanted to talk about was corruption.

I found that, first of all, really interesting because we have a tendency to consider corruption to be somehow cultural. Countries like Afghanistan, Nigeria, the former Soviet Bloc, or whatever, that’s “part of their culture.” Whereas it was Afghans who were screaming about it, and the Americans and other international interveners were much less concerned about the corruption that they were one way or another participating in and sometimes even enabling. Yet still, for years, I thought that what I was dealing with was a phenomenon specific to this Afghan context.

Then, around 2010, I gave a talk about drugs to a multinational audience. I couldn’t resist at the end of that talk, including a slide showing that narcotics were not a standalone issue. That narcotics, in fact, was part and parcel of the corruption issue because so many government officials in Afghanistan were very wound into the drug trafficking networks.

I talked for five minutes about how corruption is not, in fact, a single scandal or an aberration because of one greedy official, but rather, it’s an operating system of a whole sophisticated network. After that talk, people came down to me to say, “Oh, my God, you just described my country.” I was looking, and the countries were spread across the globe. Interestingly, to me, many of them had what you could consider ideological extremist insurgencies that were attacking the government. I started to see that pattern.

Then I spent much of the next, I would say, half dozen years galloping around a lot of these countries like Nigeria, as you mentioned, and Uzbekistan, Egypt, various Arab Spring countries, in fact, Latvia, just a number of quite disparate countries on different continents. I discovered that although I had no area expertise in any of these regions; I don’t know much about Central Asia. I had never been to Africa or Latin America before, sub-Saharan Africa. Yet I knew the questions to ask, and I saw the very same patterns showing up time and time again.

It doesn’t mean that the way these networks operated was absolutely identical in every country, of course. It doesn’t mean that the revenue streams they captured were the same. But nevertheless, there were really significant parallels from country to country to country.

Even when my second book, Thieves of State, was published, I warned, this was in 2015, I warned this ain’t just developing countries. This is us. I was looking at 2008 and what had happened. I took a snapshot of Ireland, Great Britain, and the United States, and I said, It’s happening here in the most developed countries, too. Just like in places like Nigeria and Afghanistan, it is going to lead to crisis. I thought that crisis was a little bit further down the road, and it turns out that it started to hit around 2016. Then, it became obvious that I needed to write about my own country, the United States.

Talia Baroncelli

What role did SIGAR play in your understanding of the issue? SIGAR being the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction. They published numerous reports on the corruption in the Afghan National Defense Security Forces, and how once the U.S. withdrew from Afghanistan, the Afghan Security Forces basically collapsed and weren’t able to fight the Taliban due to the corruption, which was endemic in their forces. What role did SIGAR play in your understanding of the problem, if at all, or did that come much later?

Sarah Chayes

Yeah, a lot later. SIGAR didn’t exist when I started working on corruption in Afghanistan. I didn’t need an outside report. Ordinary Afghans were coming to me starting in 2002. Immediately, Afghans were coming to me. I was setting up a radio station and brought together a focus group of young people. I wanted to know what they wanted to hear on the radio. Within half an hour, we were talking about security. But they didn’t mean security against the Taliban. They meant security from the militia of the guy who had shoved his way into the position of governor because that militia was setting itself up on street corners and shaking people down for money.

Unfortunately, that militia had been the United States proxy in its initial fight against the Taliban in 2001. These militiamen were wearing U.S. army uniforms. This is way back in 2002 when people were complaining about this. The problem was that, from their perspective, these militiamen were wearing American uniforms. Therefore, the United States must be in support or in favor of the crimes that these militiamen were perpetrating. That was the refrain that went on for the whole decade that I lived in Afghanistan, that from the perspective of Afghans, the whole American establishment in Afghanistan was enabling and reinforcing the corrupt shakedowns of ordinary people. They couldn’t understand it. They said, “Why are you trying to hurt the very population that you say you’re supporting? Why are you allowing the government that you are paying for, arming, making the police, and paying the salaries of everyone, if you’re paying their salaries, you should have some say in how government officials are treating the population.” This was a message I, in 10 years, was not able to get through to American decision-makers.

Talia Baroncelli

We currently have a problem of monopoly capitalism in which so many of the defense contractors, particularly in the U.S., such as Lockheed Martin and Raytheon, have a monopoly in the defense sector. It means that they can influence pricing but also influence what munitions are produced and at which rate they’re produced. They can make certain contracts with the Department of Defense. Arguably, they have a huge role in determining U.S. foreign policy.

The reason I bring this up is you were writing a lot about the Gilded Age and also the ’20s and the ’30s. In the ’30s, there was a report led by U.S. Senator Gerald Nye called the Nye Commission. This investigation interrogated the role of bankers, the banking sector, and the arms industry in leading [Woodrow] Wilson to enter World War I. Regardless of what the conclusion was of that report, I think it’s safe to say that they also shaped the foreign policy dimensions at the time. I wonder how much of this monopoly capitalism analysis factors into your understanding of the problem of corruption?

Sarah Chayes

I love the example that you just offered, Talia, because I think you can look at those two sectors, the financial industry and the defense sector, and both of them control a great deal of how the United States government operates both on the foreign and the domestic levels. To be honest, I think that’s true in a great many other countries around the world, both developing and developed.

To return to the United States, that example raises a couple of points. One is we often talk about the revolving door between the private sector and government. You use the expression monopoly capitalism, but I would invite us to think about it in another way: as a strand in the horizontally integrated network, kleptocratic network, the horizontally integrated kleptocratic network. In that light, you can also revise your understanding of the revolving door, which implies that it’s just a single individual who’s pushing a door from his job in industry to his job in government or in the other direction. If you start to look at the entire sector of financial services or defense and the Pentagon, the Treasury, the Federal Reserve on the one hand, and defense contractors, banks, and money managers on the other, you start to see it’s a highway connecting public and private. What you have is a weaving of this kleptocratic network by constant exchanges of personnel between the public and private sectors in both of those spheres, defense and finance.

If we return to Afghanistan, the results are devastating. On the defense side, what you had was vast expenditures of U.S. taxpayer money, creating an army and police in Afghanistan that were completely unsuited to the nature of the conflict. We were creating a standing conventional army that required incredibly sophisticated, expensive, and difficult-to-maintain material in a place that is coated with dust like talcum powder, mountainous, very difficult terrain with not a deep bench of well-trained operators or maintenance experts.

On the other side, you had the Taliban who didn’t have any of this stuff. I kept hearing for years about how the Afghan National Army could fight on its own. It just needed medevac and close air support. I’m like, well, wait a second. The Taliban don’t have close air support, and they’re doing fine. As you suggest, it was clearly this mindset that had been built up over the years by the defense industry that its gadgets were the best way to wage a war that caused us to make a fantastic mistake in military terms, purely military terms, in the way that we addressed the challenge in Afghanistan.

Then, on the banking side, what you have is the very same sector. Starting in 2002-2003, the decision was made to create a formal banking sector in Afghanistan. Who does that? Financial industry professionals from the United States. Now, 2002-2003, that period, what’s happening in the United States in the banking sector? We are inflating a massive bubble right through systemic fraud. That’s how the crisis of 2008 happened. Systemic fraud was being selected for by the incentive structure in the banking industry. That’s the same people who created the formal banking system in Afghanistan, which turned out to be an absolute Ponzi scheme. The United States government was running the salaries of all of the Afghan Defense Forces through Kabul Bank, which had practically a billion-dollar hole in it. Approximately a tenth of Afghanistan’s GDP was the hole in Kabul Bank, which was discovered in 2010. The failure driven by the capture of those two sectors that you mentioned, defense and finance, resulted in the worst defeat of the United States on the battlefield since Vietnam for quite similar reasons.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, it seems like what you’re describing is a large conflict of interest that exists internationally. You have companies or private asset managers, such as BlackRock, State Street, and Vanguard, who are heavily invested in the domestic debt of certain countries. I’m thinking of Sri Lanka, for example, which has numerous debt or international sovereign bonds that have been issued by BlackRock.

Also, in other contexts, private asset managers are heavily invested in the border and surveillance industry in Europe and the United States. You have this instance in which the boards of these companies are then shifting and taking on roles as politicians in the political sphere and then going back to the boards of these companies again. I don’t want to use the metaphor of the revolving door because you pointed out that that’s not really an accurate or adequate description of the corruption issue. It does seem like there needs to be a different regulatory framework. Or is that not the right understanding of it? Is it just that we have the right rules, but they’re just not being implemented properly? Is it a problem of enforcement? Or would you say that we need a completely different regulatory framework as well?

Sarah Chayes

Both. That’s, again, a really great question. We could return to BlackRock, too, because there are some very interesting issues to do with BlackRock. But the fact is number one, that since about the late 1980s, the Supreme Court of the United States has been narrowing and narrowing and narrowing the effective legal definition of corruption to the point that today you have to be practically jailable for stupidity to commit a crime that would fall under this very mincing legal definition of corruption. It’s become almost impossible to prosecute corruption even under the laws as they stand. But I think your suggestion, your initial suggestion is actually right; that those laws are way too straight-jacketed to address the real issue.

Let’s take another American situation, which is that of the son of President Biden, Hunter. Now, again, no false equivalencies here. No one has spoken as loudly about former President Trump’s children, who were openly and almost ostentatiously making use of their father’s influence to feather their own nest to the tune of tens of millions of dollars. But to look at Hunter Biden, well, he was very clearly monetizing his last name, let’s put it that way. He had no experience in the domains in which he was receiving positions and being handsomely paid.

I think you also suggested another example, which is former officials going on to boards of directors and then returning to government service. Another model, particularly in the foreign field that I’ve noticed is quite similar to that is people who leave the U.S. State Department or Foreign Ministry and then set up consulting firms. They offer businesses advice on how to conduct investments and other business practices in foreign countries. Then, on the side, these same officials will set up a hedge fund. They will then be making investments based on the insider information that they obtained through their consulting practice or through their prior diplomatic experience. I’ve seen several examples of this. It’s almost become common practice. All of this stuff needs to be severely curtailed.

What that would imply in terms of legislation would have to be a dramatic tightening of, to use your expression, the conflict of interest laws and the revolving door laws. Much higher standards for when an official would need to recuse themselves or business that they could not undertake for a significant amount of time after they leave office.

I think what we touch on with this aspect of the conversation gets to ethics and what is people’s motivation. If your motivation is money, if you are in the mindset where your social standing is measured by the number of zeros in your bank account, then you should not be in government service. Government service should, I think, appeal to people on the basis of a completely different motivation, which has to do with the good that they can do for their fellow citizens and, ideally, for people around the world. It’s not that they should be poor and making that commitment, but once you start to confuse your bank account with your public service, everyone’s in trouble.

Talia Baroncelli

A lot of your book also speaks about the ’80s as this really seminal decade for the financialization of the economy. You speak about how, I guess it would have been in the early ’80s when you graduated, you saw so many people, so many of your fellow students and colleagues who were going into the financial services sector. I think the way you analyze it is that you were thinking to yourself, why are people going into this sector rather than actually doing something worthwhile that has an effect on people that actually produces something tangible rather than just contributing to the financialization of the markets and to all the accompanying speculation that comes along with it?

One thing I thought was really fascinating is how you allude to two really important films from the ’80s, namely Risky Business with Tom Cruise and Money Never Sleeps, the film that was directed by Oliver Stone. You speak about how these films show how money has been so fetishized, and this striving for constant profit maximization is something that’s so embedded in U.S. hegemonic cultural norms, so to speak. Maybe we could speak about how important these values are of just making money for money’s sake, as well as the financialization of the economy and how that has really torpedoed and accelerated the global inequalities that we see.

Sarah Chayes

It’s a crazy book. This book, Everybody Knows or On Corruption in America, depending on which version of it you happen to see. It’s a crazy book because it does talk about the time periods that you have mentioned, but it also brings in myth. Very early in the book, I look at the myth of Midas. I’ve found that an incredibly instructive story to contemplate, to meditate on.

Today, when you talk about somebody having the Midas touch, that’s seen as a positive. It’s absolutely extraordinary because the whole point of the myth is that within seconds of winning the power that he had wished for his entire life, to turn whatever he touched into gold, King Midas understood what a deadly, fatal, horrific threat it was to everything that he held dear. To me, what I brought out of that story is the idea of the Midas disease. The Midas disease is this compulsion, this race with no finish line to accumulate ever more and more and more and more and more. It’s not gold anymore. It’s not even a physical substance. It’s electronic signals in a bank account.

The other thing that your question raises is the matter of the calendar. I’m often asked whether corruption isn’t just a constant in human society. Of course, to some extent, it is. But what I did discover in doing the research for this book is that the degree of capture of the political economy by people intent on amassing ever more money has come and gone. It hasn’t been a constant.

The first real period of that was from about 1870 until about, I’d say, 1935 or so. Then it subsides, and the question is, why? The answer is a very sobering one. It is that very disease, the Midas disease, that had captured countries across the industrialized world, regardless of not just a political party but a political system, that disease drove the world into World War I, World War II, the Great Depression, a pandemic, rivaling the one that we just lived through. Ironically, crisis tends to bring people together. It’s my hypothesis that it was this series of global cataclysms that led to about 40 years when the type of congressional hearing that you mentioned could actually be held, that very significant hearings into the causes of the Great Depression were held and enormous, quite radical reforms were enacted during the New Deal period and in the 1930s across Europe as well.

That bought us, I would say, about 40 years when struggles for greater rights, both for labor as well as women, people of color, the environment, consumer protection, the independence movements in the former colonies, all of these things, they were fights, but at least they had some hope of succeeding.

Then you get, as you just said, Talia, to the 1980s when the pendulum seems to start swinging backwards again. As you suggest, it seems to me that it starts on the cultural level where you see the Reagans quite apart from the deregulatory frenzy that was unleashed in the Reagan administration. But Ronald and Nancy Reagan were flaunting riches in a way that would have seemed really tacky 10 or 20 years ago. People like my generation of college graduates were going into finance when our older siblings wouldn’t have been caught dead on Wall Street. They were all smoking pot and listening to wonderful music.

What’s ironic about Risky Business, for example, is that it was meant as a parity. It was meant to ward people off of this type of lifestyle. Yet, at least ostensibly, that’s what it was meant for. But if you look at the unspoken message being sent, it’s that money is cool. Breaking the law in order to get rich is cool. Who gets the girl in the end? The little cheating teenage boy. It was dubbed a coming-of-age movie. That’s an interesting rendition of coming of age. Coming of age in the 1980s really meant go for the gold, go for the money; that’s where it’s happening.

Unfortunately, that ethos has taken root and continues to. It was, I want to say, reinforced by the Democratic administration of Bill Clinton. Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher get hard with the brush of deregulation, and they deserve it. But what we often forget is that the Labor and Democratic Party successors to those governments really rubber-stamped a lot of the changes that they made. The problem is that if it had just been Reagan and Thatcher, then it might have been possible to say, well, this is just an aberration. This was an obscene eight-year aberration. Now, let’s get back to a more sober and respectful, less wanton economy. But once you had the other political party rubber-stamping this ethos, then it becomes a bipartisan consensus. The result, I want to say, at least in the United States, has been that we now have approximately half of our electorate that doesn’t even bother to vote.

Because on these issues, on this moral, economic, political juggernaut, really both of the political parties behave the same way. You can see that I mentioned earlier this series of Supreme Court decisions that have been narrowing the legal definition of corruption in the United States. What’s fascinating is that they are all unanimous on these decisions, except one, which was seven to two. But Americans keep talking about how divided the Supreme Court is. It turns out that on these issues, the court, just like the political parties, are basically unanimous. That leaves nowhere to go for the ordinary people who rightly identify corrupt practices all around them at the local, regional, and national levels.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, I think it’s very important that you point to the bipartisan nature of this corruption. I think when it comes to issues of corporations and corruption, the U.S. Supreme Court is, for the most part, unanimous in how it makes its decisions, and it’s more divided on some of the other cultural issues. I think it’s easy for us to point the finger at the other side of the aisle, at the Republicans. There’s a great documentary from Adam Curtis on the ’90s and how it was really under Bill Clinton that the financialization of the economy was cemented, so to speak. It wasn’t just the Reaganites and the Saturates, but a lot of that was really cemented and put into place in the Clinton era.

Sarah Chayes, it was really great to speak to you today and to get your insights on the origins of this myth of money being the source of corruption and greed and tying that to a lot of the phenomena we see today on the global scale. Thank you very much for joining me.

Sarah Chayes

My pleasure, Talia. I’m delighted that you’re doing this because I do think that this phenomenon is driving just about every one of the more, I want to say, apparently dramatic crises that we’re facing in the world. Last time around, it led to two world wars, a Great Depression, and a global pandemic. I guess I’m wondering, if we don’t address it, what is the scale of the global calamity that lies in store for us now? So thank you.

Talia Baroncelli

Thank you for watching theAnalysis.news. If you enjoyed this content, please go to our website, theAnalysis.news, and feel free to make a contribution by hitting the donate button at the top right corner of the screen. Also, don’t forget to get onto our mailing list. That way, you’re updated every time there is a new episode. See you next week.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | TuneIn | Deezer | RSS

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter

Sarah Chayes is a former senior associate in the Democracy and Rule of Law Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and a former reporter for National Public Radio; she also served as special advisor to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Fabulous interview, but way too short. Areas not really covered: the press and media, higher education (sic!), and elections in general. Sadly, nothing will be done until enough people cannot afford to survive that everything will be overturned; when enough people, a critical mass of people have nothing to lose. That is where we are headed, and the ‘smart’ folks at the top are only encouraging that.

There’s PLENTY of corruption IN US POLITICS at HOME!

Voting is a joke……what do you really GET when you vote a candidate for office…? SOme pre cooked agenda, which only the media and insiders KNOW but do not relate.