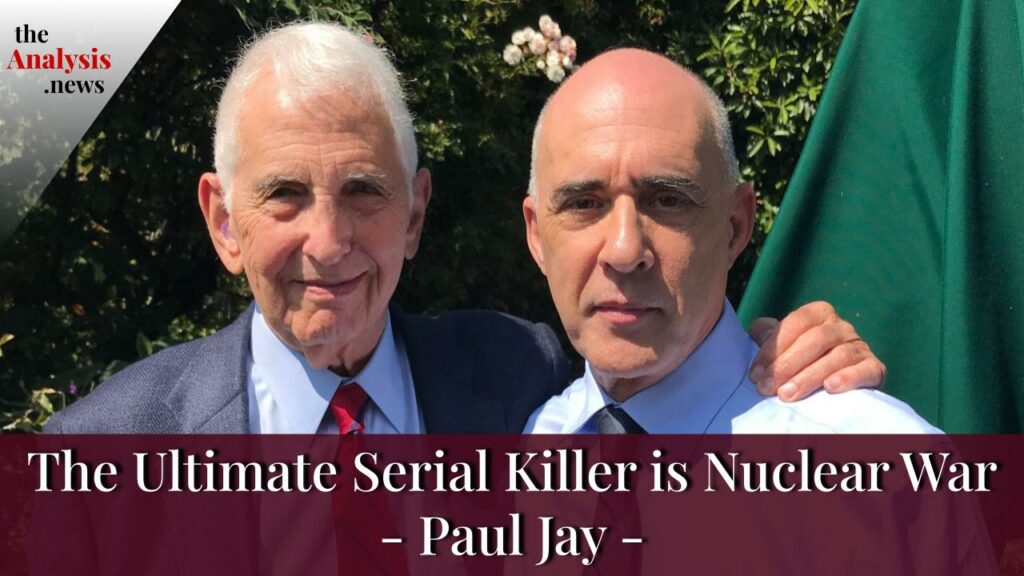

Noam Chomsky and Daniel Ellsberg continue their discussion about how to avoid nuclear war.

To view part one of this interview, click here.

Noam Chomsky

Well, let me shift gears a little bit. You’ve had more experience than anybody I know of with trying to protest the race to nuclear war over these years.

Daniel Ellsberg

It’s not because anyone actually wanted a nuclear war other than, and I don’t say this as a joke, General Curtis LeMay, I think, did want it earlier than later because it was going to be harder later. In the earlier years, he had a few acolytes, but really almost nobody else and nobody now. I’ll bet there’s nobody now who wants a two-sided nuclear war.

Noam Chomsky

Let me rephrase the drift towards nuclear war, whether you want it or not. What do you get from this experience about the ways to proceed that are effective, those that aren’t effective in trying to arrest the drift that is inexorable? It’s just going to keep going one step after another up the escalation ladder. China is going to react in some way, I presume, to the Aukus deal, nuclear submarines off its shores, to the station of B-52s permanently in Darwin, Guam, and maybe expanding in the Philippines to the economic war. How do you stop– what are the best ways to proceed to try to prevent this continual step towards what could turn out well to be a determined nuclear war? While the conception in planning circles is, well, we can keep calibrating it, keep gaining step-by-step, degrading Russia, undermining China, moving forward, more provocations, but somehow we can keep it under control. What is the way to get people to understand this?

Let me just bring one fact into this, which is shattering, in my opinion. I think maybe I’ve mentioned this. The Pew polling centers just did a study a couple of weeks ago of the issues that Americans find urgent– how do they rank a couple of dozen issues in terms of urgency? They didn’t even ask about nuclear weapons. It’s considered so low a priority that they don’t even raise the question.

Daniel Ellsberg

As I think, you know, Noam, we’ve discussed this. I don’t know the answer to that question. I would say that the things we’ve done and Noam, you know, when it comes to [inaudible 00:03:08] understanding to oppose these things, you’ve been at that much longer, and you’ve done it all over the world. You gave me the understanding that I’ve worked with for the last half-century and more. No one has influenced my thinking and my understanding of the world, no one more than you. As I’ve told you before, there’s been others that definitely have been my teachers for years: Doug Dowd, Peter Dale Scott, Tom Riffer, my former student, that you know, who’s been my mentor now for the last 20 years, and 20 years before that. But you, above all.

I was just looking at this book because I thought there was a quote in it– just a few minutes ago—American Power of the New Mandarins. I’m going to have to, in my remaining time here, this is one of the books I want to reread. I just started looking for it for what I thought was a particular quote, which turns out to be a theme in the book, which runs all through it. The phrase that I was looking for that I remembered was, “our leaders act, and our people act. It’s unquestioned. It’s unchallenged. As if he had a right to determine the institution, governing powers, and the police.” It’s an imperial latitude of; that wasn’t a word that you emphasized. The fact that we acted, if we had the right to intervene, to invade and occupy, to threaten all these things.

I came back in ’67. I just looked at it when this book came out. This is a later copy. It was in ’67 and ’69. I don’t think I read it as soon as I got back, but I read that, and I said, right, right. The question of right to do this. I’d been in the government a dozen years by that time, including the Marines. I’d never heard any mention, anyone mention that consideration– to have a right. Could it be that we don’t have a right to some things? Well, it’s not as though people claimed they had a right. This question just didn’t arise, as you pointed out. They act as if they do, and that’s not only the leaders. That goes, as you say, unchallenged, not only by the elites but by the people.

When I was reading this, my first reaction was the old one– when I learned what was going on in Vietnam, it was two years there, visiting 6-38 of the 43 provinces. I came back in the ’60s, having been all over Vietnam. I reassessed, for example, that the public did not understand that this was a never-ending stalemate. It was clearly a stalemate. Well, one reason they just said LBJ had explicitly in writing, that is, the White House forbidden the use of the word stalemate. It was taboo. Progress, progress, and so forth, no stalemate. So my message was very [inaudible 00:06:33] to other people, like assistant secretaries of state, like Robert McNamara himself, Secretary of Defense, who agreed with me, by the way. In fact, they pretty much all agreed with me, but they didn’t say it. We are stalemated in ’67. And actually, the Tet Offensive didn’t change that so much. It never changed until the end, pretty much. Okay, relevance to right now, of course. Of course, it’s a stalemate there now, as European World War I was in 1916.

I’ve just read a very interesting book. You’ve probably read it, or maybe not. It’s by Philip Zelikow called The Road Less Traveled; I think it’s called. It’s about the fact that the leaders with Woodrow Wilson, [inaudible 00:07:24], Germany, the French, and the British all understood that the war then was stalemated—a trench line from one side of Europe to the other. Had we moved at all for negotiation, and they considered it, and then they were over. I said, no, one more offensive right now because each side believes that it will make some progress with another offensive. Now, I believe, as in Europe, they will find they will fail on both of those, or we’ll see. I don’t think it’ll be any decisive thing. Will there be another chance then, after they failed in the spring, to negotiate in the way that, as you know, Zelenskyy was ready to negotiate a year ago in April? Hardly anybody knows this. The mainstream press never refers to it. Yes, both Putin and Zelenskyy had their representatives in Iran, I think it was; not Iran, Istanbul, and under Turkish auspices, and had an agreement with Boris Johnson flying over from England to say, “we do not agree to concessions at this point, to compromises, to a ceasefire. The war must go on.” And then he quoted, he says, “the US agrees with me.” The US confirmed that. Now, whatever the complexities and the complicity on both sides that got us into this situation, there were delusions on both sides. Obviously, Putin had the delusion that it was going to be a cakewalk. That is what you used to hear about Iraq. Remember that war? Iraq was going to be a cakewalk. The Gulf War was– Putin obviously thought it was going to be a cakewalk here, and he was wrong. He wasn’t wrong alone. Everybody had delusions. This is what’s going to happen. It’ll go very quickly, and the US will get most of the benefits I’ve spoken of. Arms sales will go up. NATO will go up. This is not an unwelcome thought, I think, to American leaders, but they weren’t looking at a war like this because no one was.

Who in the world predicted a year ago that this is where we’d be now, with 100,000 losses on both sides? I think no one expected that. So delusions go into it. But as in World War I, the delusions are shown wrong within a month or two. You know, the trench lines developed in Europe. The machine gun showed what it could do. Putin even knew within a month that his delusion, widely shared, was wrong. At that point, for the US to discourage compromise, negotiations, and discussion, to avoid where we are now with the risk of nuclear war looking at us was a historic war crime, a crime against humanity. It was– I’m not letting Putin off the hook here either. Apparently, he had some– facing the reality to draw back to pre-24th positions, which I don’t think are in the cards anymore. After the 100,000 loss on each side, what leader side is going to say, “true, we made a mistake. I’m terribly sorry. I’m calling this off.” Nobody has ever done that. I don’t think– it’s going to be very hard. Is the public demanding it?

I thought in ’67, if the [inaudible 00:11:14] only knew how stalemated we were, if LBJ knew. What I found out is he did know, and he’d known all along. So that wasn’t good enough. So I thought, well, maybe if I inform the public that the executive branch has always known not that the war could not be won, but the Joint Chiefs always said stupidly that it could be won, and the Pentagon Papers are full of that. They were always saying, let’s escalate. If you just do what we want, like in the current case, Crimea, sure. We can let go of Donbas. I don’t know what they’re hearing on the Russian side. Kyiv, why not? So they were all saying it could be won, but not at what the president was willing to do. What the president shows consciously was an escalating stalemate that would postpone and avert him from ever having to say, “we’re out. We lost. It was wrong.”

Well, right now, what I found then telling didn’t do the job. A lot of them knew it, but they wouldn’t say it. They were afraid of being called names, as is happening now with anybody who describes negotiation. They’re being called appeasers, weak, weak on aggression. There is aggression here. We’re awarding the aggressor. Words like that– you’re weak on communism. We don’t have communism anymore, but we have Russia back. They’ve always wanted China back when it was built up enough to be a real threat because we need a threat, an indispensable threat, an enemy.

The problem is, though, another part of the problem is if the people only knew, and here’s where I’ve had an unease about some of the things that even you have said, Noam, continuously, I think I’ve said this, that the people don’t want to do this. They don’t want tyranny. They don’t want torture. They don’t want aggression. They don’t want an invasion. That’s true, they don’t want it, but they’re easily persuaded that it’s the right thing to do. Humans, I have to say, not just Americans, are so suggesting that they’re leaders with enormous thrones, and as you’ve described in American Power, with the media, Congress putting it out, bought by the oil companies, bought by the arms industries, this need of enemies. Humans, I think, have a flaw here. They’re not necessarily aggressive by nature, but they can easily be persuaded that they are in danger from these other people. Quote, “other”. Not like us. Different language. Different culture. Different– they are enemies. They threaten. They’re apprehensive. We have to go kill them. And so that is a problem in human nature. It makes it very hard to avert the Democrats who profit from this enemy concept and the war concept. It is in their interest to fool people, and it’s not that hard to do.

Now you’ve been at this, as I say, much longer than me. What do you conclude? Everything was tried, but it hasn’t worked yet. More of the same. Something new. I’m asking you.

Noam Chomsky

I wouldn’t exactly say it hasn’t worked. It’s had its effect, as you pointed out. Although the anti-war movement in the ’60s was way too late, it did get to the point where it may very well have prevented Nixon from using nuclear weapons. That’s not a small movement.

Daniel Ellsberg

No, no, definitely. As an insider, I can say it definitely kept a ceiling on the violence, which could have been far greater if the president had done what the Joint Chiefs wanted him to do and recommended. A major reason why he didn’t do that was the understanding of the anti-war movement and the pressure of the anti-war movement. That was very important. That saved millions of lives. It didn’t end the war, but it saved millions of lives.

Noam Chomsky

And then it continues. When you get to the 1980s, look at 1981 or so. As if Reagan or his advisors were trying to pretty much duplicate what Kennedy had done 20 years earlier– White Paper about the communists taking over the world, we got to go to war in Central America, and so on. Well, there was so much. In the ’60s, nothing happened. Nobody paid any attention. In the ’80s, there was such an outburst of protest from popular groups, church groups, and others that they had to back off. It was horrible enough what they did in Central America, but it wasn’t Vietnam. You go to the war and invasion of Iraq. First time in history that there’s been a huge protest against the war before it was officially launched. Well, I think it probably put some constraints on what they were able to do and was, again, horrible enough. It could have been worse.

Let’s take a look right now– just to add to the cheery aspect of all of this. Let’s take the Middle East. January, just last month, the United States and Israel carried out their largest joint military exercises ever, planning for an attack on Iran. The US ambassador to Israel informed them that you can do whatever you like. We’ll have your back. Are they planning for a war against Iran? Well, suppose they do. It’s kind of like Russia. Iran doesn’t have nuclear weapons, but they can react. They can send missiles to destroy the major energy sources of the world in northeast/south Saudi Arabia. It’s well within the reach of their missiles. They’ve already demonstrated they could do it. Where do we go from there? All of these things are building up. Nobody talks about it, just as in the early ’60s, no one was talking about the build-up in Vietnam. It’s as if these guys are planning, and you can understand the rationale and this concern now that the world may move to a more multipolar structure. The US allies in the Middle East, like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, they’re drifting away. They’re beginning to make moves towards accommodation, not only with Iran but with China. The UAE is the major hub for the Chinese-Maritime silk route. The US is kind of losing its control. Well, one way to bring them all back together, like getting Europe into Washington’s pocket, is let’s go to war against Iran, then they’ll all join together. If Iran reacts, they’ll be attacked, and we’ll have them under control. It seems that this kind of thinking is pervasive and doesn’t stop. The failure to mobilize against it, the mobilization was too late. Should be planning in advance, saying, look what’s going on. I have to do something about it. You have people who are like– there was a report about the joint military axis in the Intercept, but it has to be amplified. We have to bring to people, this is what your elected representatives are planning. They’re planning to calibrate the war in Europe, so it’ll be a stalemate, and we’ll get a bargain. Degrade Russia while we move to attack China, build up the war, the provocation/escalation in China that we’ve been discussing, and maybe we’ll keep it under control. Let Israel– to support Israel, we have to provide the refueling and so on and so forth for a bombing of Iran. Maybe that’ll blow up and bring the Arab states back into our control once again instead of drifting toward multipolarity. This planning is constantly going on. We react, but too late. Have to find ways to get there in time.

Daniel Ellsberg

So how to do it in time?

Noam Chomsky

All we can do is try to escalate our efforts to take arms against a sea of troubles, to pick a famous phrase, and maybe you can even overcome them. What else can you do?

Daniel Ellsberg

You’re certainly not talking to somebody now who is trying to tell people to stop acting, try, don’t take any risks. The difficulties are greater than I understood 50 years ago, and in part, because not all the people, even when they know we’re moving toward war, are against that. I’m sorry to say it seems easy to persuade them that this is inevitable, it’s necessary, and it’s what we have to do. It’s easy to fool them. Look, that doesn’t mean it’s impossible to change. Let me go back to the positive side. As you said, which I agree with, I said the anti-war movement, starting with me, with you, to a large extent, with what I learned from you, Howard Zinn, and others, did keep a lid on the war. I think in 1969– there’s a movie about this coming out on March 28, actually. The Madman– something like that. The Madman and the Bomb. I forgot the exact title. Steve Ladd and others are producing this. It is going to come out on PBS. It’s about the moratorium that was really a general strike during a work day, a weekday, in which people took off from work and took off from school to protest the war. It was two million people. It was a general strike, but they didn’t want to call it that. It sounded too radical, too provocative, so they called it a moratorium. I didn’t know. I didn’t know at that time, when copying the Pentagon Papers, that Nixon was planning to escalate the war, including nuclear threats in nuclear war on November 3. The two million people on October 15 showed him he would have ten times that many if he did what he was preparing to do. He didn’t do it; the escalation. So it carried out an enormous– it stopped an enormous escalation.

I’ll tell you another. Now in Vietnam, it didn’t stop the war. The war went on. The Pentagon Papers did not stop the war. It did not stop Nixon’s planning at all. The biggest bombing of the war in the offensive took place a year after the Pentagon Papers, and Nixon was elected in that year (1972) in a landslide. It’s a year and a half after the Pentagon Papers, which didn’t, however, point at Nixon. Unfortunately, they ended in ’68. To speak of miracles that are possible, I always cite the ending of the Berlin Wall and [Nelson] Mandela becoming President of South Africa without a revolution, impossible years beforehand to imagine this low likelihood, but impossible. Yet they did happen.

I’ll add one that I know better than most people in sight. I know Nixon was planning to renew Vietnam as soon as American troops were out. Ground troops were out in the spring of 1973. The Paris Agreement was not meant in Nixon’s eyes to end the war. It was meant to get US troops out and carry it on by US airpower in support of ARVN troops, which we were totally financing, totally equipping, training, and everything else. Like Afghanistan, the role of our ground troops after a few years came down to involve almost no casualties. How long could you carry on a war like that? Well, we learned in Afghanistan, 20 years, Nixon wasn’t forced out by an anti-war movement. He was against that war when he was vice president. He wanted to be a lord. He was determined to get it out in the worst way, as they used to say, and that’s how he did it, in the worst way. He got out, and 20 years, well, that’s what Nixon had in mind for Vietnam. Hardly anybody understands that or believes me when I say it. It can’t be absolutely proved, by the way, but that’s a long story. There’s a lot of evidence for it.

How did the war end? In January of ’73, the second of my trial was being sworn in. It was a break in my trial. The trial started in ’71, and then in ’73, we’re starting basically a new trial. Who would– the war I knew, and Mort Halperin knew could not be ended by the anti-war movement, anybody else, or the Vietnamese, no matter what they did. With Nixon in office, he just experienced a historic landslide, by some accounts, the greatest landslide in history. What was the chance that Nixon would be out so that the war could be ended before 1977? This is in 1973. Zero. It was not unlikely; it was unimaginable that Nixon would be out so that the war could be ended because it wasn’t going to end with Nixon. The anti-war movement alone could not do it. A whole chain of events took place. Nixon’s fear that I could document his plans and the threats he was making led him to take crimes against me, which were very unlikely to be found out, were almost impossible that the president would be held accountable for them. Then John Dean takes on the president, calls him a liar, and that the crimes he’d been doing. It’s very hard to get this thing off, it appears, and that’s how World War III will start in the end, by the way. A digital screw-up of some kind, as happened in 1970, 1980, and 1995 for Russia. A mistaken message.

Anyway, if Alex Butterfield had not revealed the taping in the Oval Office confirmed what John Dean had said, Nixon would have remained. It was unthinkable that Alex Butterfield, in that Oval Office for many years, taking down notes and everything, would be the one. There was only a handful of people who knew that taping was there. John Ehrlichman, for example, was not one of them. Alderman did know. Kissinger did not know, but Butterfield knew. The idea that Butterfield would reveal that was worth thinking about. He chose to do that, tell the truth about the taping. Without that, Dean was nowhere. He had no documents to prove it. That was essential. Without Supreme Court justices that Nixon had appointed being willing to say, he had to turn over the tapes. Alex Cox [Archibald Cox] saying, I have to have the tapes. Elliot Richardson saying, I resign, rather than fire Alexander Cox, his Harvard Law School teacher.

[Inaudible] being the second in command brought in there, I won’t do it either and comes back to [Inaudible], who was willing to do it. But even so, the tapes got out, etc.

So Patricia and I, Tony Russell, Lynda Resnick Sinay, who had helped the Xerox, Randy Keeler, who was the person who went to prison and whose example was cruel to me in saying, I do to help end the war, I’m ready to go to prison like him. None of those people, including me, had any reason to think there was any chance or much chance, much chance of shortening the war. They did what they could, and each one of us, each one of them, was a link in a chain of events– here’s the point I’m making– that led to an actually unforeseeable event of making the war endable nine months after Nixon left office for the first resignation in our history. So I’m saying if you push on every door, as you’ve been doing for much more than half a century, you don’t know which one will open or make any difference, but it is not impossible that you will make a difference. The Pentagon Papers happened to be a proof of that. It was not just the Pentagon Papers, but the fact that I had copied other papers on Nixon that scared him into taking people to incapacitate me totally, to go into my former psychoanalyst office, to get information, to coerce me, to blackmail me into silence and that that should become known and so forth. All of these things were unforeseeable, but all of us were doing what we could. You, as I said the other day, you and Howard Zinn, and Dick fought (a teacher of mine), had copies of the Pentagon Papers before they came out. Did that end the war? No. But I thought to know you above all should know, but it’s not surprising to you. It made a difference until things came in.

So, Noam, you were a big part of that, definitely. As I said, you’re the one who put the idea in my head. We don’t have a right to be doing this, and we don’t have a right to make nuclear threats. No one does. Putin does not. Kennedy did not. [Nikita] Khrushchev did not in 1962. They all talk about, “oh, this person was provoked into doing this, and he had no choice. It was inevitable.” Yes, that’s the way they told everybody. The way people accepted bullshit. They were making choices that were insane, insane risks. That’s what’s happening right now.

If you ask me, could people think that a war could be contained in China? Well, I have to say, yeah. Experience shows that. Putin thought a war could be contained in Ukraine. Yet, It hasn’t done so well. It’s still contained, as you say, it could always have been worse. Indeed, the public attitude about nuclear weapons has been a major factor in the fact that threats not been carried out. Everything is at stake.

Can it be with each of us? Randy Keilar, you, going to Hanoi and reporting back about the bombings, and all the others. We’re taking a chance of imprisonment. So for a chance that almost no official made, no matter how skeptical and cynical they were about the chances of any progress, but they didn’t reveal that outside the system because they might have lost access. They would have lost access. They would have lost their jobs, their clearances, their career, and maybe their marriages. These are not minor, minor problems. Is it worth doing that and demonstrating in civil disobedience for a small chance that you’ll have any influence and that that influence and a small chance will change the course of events? The answer is, of course, it’s worth it. Of course, everything is at stake. Everything. Look out. The leaves, the trees, everything. Your family, the babies, everything. Of course, it’s worth it. Like you, who have been doing this most of your life, does it deserve admiration and gratitude? You have gotten [inaudible 00:33:29].

Paul Jay

Noam. Last word, Noam.

Noam Chomsky

What you’ve been doing is a real inspiration. It should help us all stand up for what has to be done, no matter what the difficulties, and move on to overcome threats that could destroy us, but that we can control and overcome with enough effort and commitment. I think you’ve shown that in a way that is truly incomparable.

Daniel Ellsberg

Thank you, Noam and Paul, for giving me a chance to say that to Noam. I’ve wanted to for so long. I think the way things go, I’ve said it clearly, but Noam, you are my hero and my mentor. I’m so glad you’re my friend.

Noam Chomsky

It’s been wonderful for all of us. Still is and will be.

Paul Jay

Thank you, gentlemen. You are both an inspiration for us. Thank you for joining us on theAnalysis.news.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | TuneIn | Deezer | RSS

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter

“Daniel Ellsberg (born April 7, 1931) is an American political activist and former United States military analyst. While employed by the RAND Corporation, Ellsberg precipitated a national political controversy in 1971 when he released the Pentagon Papers, a top-secret Pentagon study of the U.S. government decision-making in relation to the Vietnam War, to The New York Times, The Washington Post, and other newspapers.”

“Avram Noam Chomsky is an American linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist, historical essayist, social critic, and political activist. Sometimes called “the father of modern linguistics,” Chomsky is also a major figure in analytic philosophy and one of the founders of the field of cognitive science.”

This was a most inspiring discussion. You have changed my mind about protesting. Thank you Paul, Noam and Daniel.

Depleted uranium bomb are not nuclear weapons? Tell that to the Iraqi children born with horrible birth defects. Sharpen the conversation or Americans miss the best.