Meagan Day, a journalist for Jacobin Magazine and member of the DSA, joins Paul Jay to discuss the challenges in building a broad democratic front that focuses on the climate crisis and defeating rising fascism; and organizing a socialist movement for a more radical transformation of the society.

Transcript

Paul Jay

Hi, I’m Paul Jay. Welcome to theAnalysis.news podcast.

Donald Trump has framed this election as a conflict between socialism and capitalism. Although Joe Biden is far from being a socialist, there is something to what Trump says.

When I look at the problems facing us—from the climate crisis, the threat of nuclear war, the pandemic and the deepening economic crisis, geopolitical conflict, the inequality chasm, systemic racism, and, in the U.S, the health care crisis—every serious problem leads to a more socialistic solution. If Medicare for All makes sense, then why not public banking? If public banking makes sense, why not nationalize arms production and take the profit motive out of war? Nationalizing and phasing out the fossil fuel industry might be the only way to face up to the challenge of the climate crisis.

So, Trump and the right may be correct. Even though Biden is no socialist and represents sections of capital that hate socialism and the left as much as the Republicans do, in people’s consciousness, if they see some public ownership policy working, they may demand more. The elites fear where that might lead.

But if we don’t head towards a more socialistic approach towards climate, whether it’s called that or not, we’re headed into a world where much or most of the planet is unliveable.

Now joining us to discuss these issues and the state of the people’s movement in the U.S is Meagan Day. She’s a staff writer at Jacobin, a member of the Democratic Socialists of America, and co-author of the book Bigger Than Bernie: How we Go from the Sanders Campaign to Democratic Socialism. Thanks for joining us, Meagan.

Meagan Day

Thanks for having me, Paul.

Paul Jay

So, before we get into some of the questions you addressed in the book and looking at the state of the movement, what’s your take on where we’re at in terms of the election campaign and balancing this issue of keeping a perspective of socialism in sight? At the same time, I’m assuming you want to see Trump defeated. The DSA has suggested people should vote to defeat Trump, which does mean voting for Biden. But balancing these things.

What are you hearing from people organizing, especially in swing states, what’s happening with the working class there? Are you hearing any feedback from where Sanders is campaigning?

Meagan Day

Well, first, I’ll say that I appreciated your introduction. I think you’re correct. I think that it would be wonderful if this were a direct referendum on socialism versus capitalism, but no such luck. Unfortunately, we have to settle for an indirect referendum. But I do think that right now it looks to me like Joe Biden is somewhat immaterial to the election, that this election is actually just about Donald Trump and Donald Trump’s leadership. The question that’s facing the nation is, Do we want to continue to have a President Trump or not?

I see, like many other people, it appears to me—and I’m afraid to say—that it appears to me that Joe Biden might win. Of course, we’re all afraid to say that because we have post-traumatic stress disorder from the last time. But it does seem like a lot of people who were drawn to Trump in 2016 were drawn because they liked the idea that he was an outsider. He was a novelty of sorts. They figured that after decades of neoliberalism and advancing privatization and austerity, that their lives could only improve if a major change were implemented.

Well, Hillary Clinton, obviously bearing the Clinton brand, did not represent a change for a lot of people. And I think Donald Trump did in a somewhat apolitical way. And obviously, four years later, there’s been some time to assess whether or not the type of change that he brings is the type of change that’s going to improve people’s lives. So hopefully, we’re going to see some of those people peel away. I think also we may see some people turn out just out of sheer distaste for Donald Trump. There was a low turnout in a lot of places, a lot of very important places for Hillary Clinton, where her campaign was betting on a good turnout. A lot of that has to do with disillusionment and dissatisfaction and also a sense of complacency: the pervasive idea that there was no way that Donald Trump, given what a buffoon he was, could actually win the presidency. Well, I think circumstances have changed. So hopefully, we’ll see that translate into votes.

As for a movement, I don’t think that we’re seeing at present anything like the type of cohesive, politically coherent bottom-up movement that you saw during the Bernie Sanders campaign during the primary. I don’t think that Joe Biden and the Democrats have that. I don’t think that they’re capable of marshalling that. I think plenty of the people who were active in the Bernie Sanders campaign are throwing their weight behind Joe Biden in one way or another.

But you can’t sort of rely on people to come together with that kind of strength and intensity and commitment if you’re not also giving them something to believe in. Joe Biden’s sort of accidental slogan is what he told a room full of wealthy donors: nothing will fundamentally change. I think that a lot of people perceive that from his campaign. That doesn’t mean that people don’t back him. It doesn’t mean that people aren’t volunteering or phone banking for him. It doesn’t mean that people won’t plan to vote for him. It just means that the energy is not there. To the extent that there is energy, it seems to be anti-Trump energy and not pro-Biden energy.

Paul Jay

Whether it was Bernie or others who were involved in the Bernie campaign, because it was clear this was needed: how come there wasn’t more organizational form given to what had become a national, very unifying campaign once Bernie lost and endorsed Biden? Why didn’t that then move into something that became a national popular front, something that gave it some framing on the bones of what was there?

Meagan Day

I tend to think that the Bernie Sanders campaigns, both of them, have essentially functioned—they’ve served the function of what a left party would look like if we had a leftwing party. So they were sort of ad hoc left parties. All of the energy was going into getting Bernie Sanders elected, and so the energy wasn’t going into making those organizational structures—to institutionalizing them for the long haul.

In order to understand why that didn’t happen, first, you have to acknowledge that organization is very difficult and very painstaking. Second, you have to reframe your thinking to concede that it’s kind of miraculous that we were able to marshal that much organization on the left for the purpose of the Bernie Sanders campaign to begin with, given that we don’t have left parties, we don’t have left institutions, and that we’re relatively disorganized on the left in the United States. So, it’s kind of incredible.

I would say, and we do say in the book Bigger than Bernie, the book that I co-wrote with Micah Uetricht, that the Bernie Sanders campaign is perhaps the exact opposite, the reverse order, of how we would have liked to go about things. If socialists could sit down and draw up a blueprint for how we would have liked to proceed to winning the highest office in the land under the name of democratic socialism, I think we would have started from the bottom, and we would have painstakingly and deliberately built durable, long-lasting institutions that would then root themselves in the broad, multiracial working class. They would root themselves in workplaces and communities that would win electoral office, starting from dog-catcher all the way up, and really implant themselves in the ordinary lives of working-class people and grow and build momentum to the point where we could run someone for president. It wouldn’t be a complete anomaly or a fluke. Well, that’s not what happened.

Of course, we should be thankful for what did happen. I think that it gave us the opportunity to go about doing the hard work of building organizations. We basically came into this with no organizations. Bernie Sanders thought, somebody really ought to run against Hillary Clinton. Otherwise, it’s essentially a coronation and business as usual, and nobody else seems to be volunteering. He had asked Elizabeth Warren to give it a shot, and she deferred. So, he decided to do it himself. I think it took him by surprise that people were ready for that. Actually, I think it took him by surprise. So, there was an ad hoc attempt to build an organization for both the first Bernie Sanders campaign and the second Bernie Sanders campaign.

Now, there have been some organizations that have come out of that, one of which is the Democratic Socialists of America, which had 6,000-ish members at the time that the first Bernie campaign was announced and at present has 75,000 members, the largest socialist organization in the United States in over half a century, to my knowledge.

So, we are seeing the beginnings of that kind of organization-building in the United States on the left. But it wasn’t there before. And it’s not a surprise to me that its ad hoc form dissolved after the campaigns were over. I think despite the best attempts of many people who understood that it would be better if that didn’t happen.

Paul Jay

There was sort of this attempt to start Our Revolution, which was a spinoff from the Sanders campaign. Was that supposed to be the mechanism for broadening and keeping the campaign going?

Meagan Day

It was.

Paul Jay

It didn’t accomplish it. Why?

Meagan Day

It didn’t. For one thing, again, I’ll reiterate that organizations are very difficult. There’s a certain magic to membership organizations that you can’t really conjure out of thin air. Our Revolution, for a variety of reasons that I won’t go into, was just not able to actually capture that.

I think the Democratic Socialists of America has a little bit more energy at the membership level than something like Our Revolution does. Which doesn’t mean that Our Revolution hasn’t been an excellent contribution politically, just that it’s hard to predict, and it’s also hard to fashion out of thin air the kinds of membership-based enthusiasm that keeps organizations alive, that gives them a beating heart, that keeps them from being something other than a front organization or an NGO with supporters who call themselves members. So, Our Revolution was the ostensible attempt to do the correct thing, which was to try to build a long-lasting organization out of the Bernie Sanders campaign.

Unfortunately, I do think that there’s a paradox when it comes to Bernie Sanders himself. We wrote about this in the book. So, Bernie Sanders managed to—we like to think of Bernie as a kind of holdover from the last time that we had an organized left in this country, who happened to still be around—not just alive, but politically active—and had managed to build a lot of political credibility and goodwill and to remain politically consistent such that he was in the right place at the right time when we had a second wind or another wind for the left in this country. So, he could provide it with electoral leadership.

Well, the paradox is that what allowed him to be able to do that, to weather all of those decades without losing his sort of political and moral commitment, is precisely the fact that he’s not a joiner. He was never really a joiner on the left. I mean, he had been active in the Liberty Union party in Vermont for a while in the ‘70s, but it was a somewhat short-lived experience. I think it was important for him but the overriding political experience of his life has not been as a member of an organization. It has been as an individual, Bernie Sanders. That’s been actually really good for him: he sort of preserved himself in amber until it was time for him to provide electoral leadership.

Unfortunately, I think that’s one of his weaknesses. I think organization-building is something that he doesn’t have decades of experience in. And I think Our Revolution perhaps would have fared better—or, in general, the attempt to build some kind of long-lasting organization coming out of the two Bernie Sanders campaigns would have fared better if he was of a different temperament or had a different organizational history, an orientation towards organizations, and so on.

Unfortunately, that’s not the case. Now, it’s OK. I mean, we have to understand that we’re started from almost nothing, and now we’ve got a lot of little glimmers of something, which means that we’re better off than where we were before. If Our Revolution is not necessarily going to be the vehicle, DSA is pretty well poised to be, if not the vehicle, then certainly an important vehicle in the process of rebuilding left organizations and institutions in this country for the long haul.

Paul Jay

In the book, you write, “We think that socialist organizations have a special role to play in building an independent working-class movement and eventually a party.” So, it sounds like what you’re saying—and maybe you actually do say it and not just “sounds like”—that DSA is kind of something for this stage. Not like, so—what’s the word?—maybe, “disciplined?” It’s not really a party that runs candidates: it backs candidates, if I understand it correctly. But you see the necessity to get to something that is a party and has a more strict organization—is that the word?—a more cohesive organization.

Meagan Day

Coherence, yeah. Coherence and the ability—I think a programmatic mass party would be the kind of traditional lefty way to talk about it, a party that could discipline its candidates, that could run candidates on its own ballot line, and that could punish candidates for stepping out of line, for compromising with the enemy once they’re in office and sort of turn their backs on the party.

You know, these are the kinds of features of a party that we would like to have. We don’t have that. It’s not just because the left doesn’t have that. I mean, nobody has that. The right doesn’t have that. The center doesn’t have that. The Republican and Democratic parties are very decentralized. They’re very incoherent compared to parties around the world. They have conventions which are essentially showcases. They don’t have conferences where members come and decide what the program should be and leaders try to put forward their vision and get members’ buy-in on it, and then that’s the program, and the people are disciplined to it, and so on.

In fact, the Republican and Democratic parties don’t even really have members in a traditional sense. You can be members of them, but it doesn’t really confer on you much in the way of being able to shape the direction of the party as a whole. Of course, there are regional and state Democratic Party structures that you can be involved in shaping, but they won’t have any bearing on the rest of the Democratic Party across the country.

So, this is just a vacuum in American politics. There’s an interesting article that will be coming out in Jacobin soon by a writer named Seth Ackerman that will try to explain why. The reason that this the case actually has to do with the way that the Constitution is written and the incredible federalism and decentralization of American politics in general. Our parties were shaped to that. They were shaped and grew up around that and so they’re very diffuse and decentralized. So, we don’t have that on the right, the center, or the left.

Eventually, we are going to have to build something like that on the left. We need to have an independent, mass, programmatic, working-class party—all of these old, sort of Marxist terminologies from a distant era. But they remain relevant. I mean, we can’t advance the interests of an oppressed class without building a party that is specifically structured to do that because otherwise, our politicians will simply be co-opted by the interests of capital. And not just co-opted in terms of bribes that have been dangled in front of them, but just by the sheer fact that the capitalist class has the ability to punish lawmakers for contravening their interests. They can disinvest; they can tank the economy. So, there’s a structural incentive to stay in line with them. We need to build an independent working-class party in order to be able to build a countervailing force strong enough to overcome that.

Now, we’re not close to that. I think that’s the point that Micah and I are trying to make in the book. We’re trying to be realistic here. It’s not going to happen tomorrow. It’s not going to happen the next day. We need a strategy to get us from A to B, and that’s where we sort of proposed the idea of—actually, I should clarify, this is not our idea. We tried to flesh it out. But in DSA circles, you’ll hear about this thing called the “dirty break.” This is the strategy that people want to pursue, which is to use the Democratic Party ballot line to build up consciousness, build up the political organization and build up our forces to make it possible to break with the Democratic Party in a way that isn’t completely self-sabotaging and rendering us completely politically irrelevant.

Paul Jay

When you say to use the Democratic Party ballot line, you’re saying run progressive candidates from within the Democratic Party, like an AOC kind of candidacy?

Meagan Day

That’s right. AOC herself doesn’t tend to talk about the need for an independent working-class party. Sometimes she’ll say things that hint at it, like once she said if this were a different country, then she and Joe Biden wouldn’t be in the same party. So, you sort of get the sense that perhaps she understands this on some level, but she doesn’t stand up there and orate about the need for an independent working-class party that splits from the Democrats. Is she an adherent to the “dirty break” strategy? Maybe not personally. It’s hard to say.

But what she’s doing is very much in line with our strategy. The idea is to run our own candidates. They should be open democratic socialists. They should have the nuts and bolts of our agenda, which right now looks like a Green New Deal, Medicare for All, tuition-free college, strengthening unions, and raising the minimum wage. These are all the kinds of things that we think are necessary for our candidates to be running on. And they would call themselves democratic socialists. But if they have a “D” next to their name, so be it. We need to get them into the office. We need to get buy-in from people. We need to not estrange people. Now, there are some districts and some races where it is going to be possible to run as independents. And we should absolutely do that if that’s the case. But we should also be intelligent about what our prospects are, which means that sometimes we’re going to be running on the Democratic Party ballot line.

The point is that we need to be building class consciousness. We need to be promoting our program. We need to be giving our activists the opportunity to build organization in the process of running campaigns. We need to be building a bench of elected officials who share our values and are willing to promote our politics.

So, a lot of leftists have shrunk from the Democratic Party. They won’t touch it with a ten-foot pole. And it’s completely understandable. I wouldn’t argue with a single reason why they have such disdain for the Democratic Party. I mostly share every single one of them. However, the question is one of strategy. We need to be making moves. We need to be making advances right now. That means what AOC is doing is great, I think, for that. And we have plenty of others, too.

In New York, for example, five members of the Democratic Socialists of America are headed to Albany to join a sixth there. You know, we’re building a bench of DSA members, the same as in Chicago. Six members of the Chicago City Council are DSA members. So, we’re starting to put this strategy into action. Of course, we have to learn as we go along what the sort of possibilities and constraints of it are.

Paul Jay

At the height of the Sanders campaign, when it looked like he might win until all the sort of corporate Democratic candidates banded together behind Biden and stopped him in South Carolina. It was South Carolina, not North, right?

Meagan Day

That’s right.

Paul Jay

At that point, one could envision going to a convention where even a majority of delegates are close to him. The majority were pro-Sanders. It gave a picture, I think, of how the fight might unfold in the Democratic Party. If the forces within the party, the really left progressive forces, gain enough strength, it probably breaks the party. It probably splits the party. I don’t think the corporate Democrats are ever going to live with the progressives taking over the Democratic Party. One way or another, they would use some mechanism to stop it.

Maybe if the Republican Party is in complete disarray after this election, and it is starting to look like that will be the case, maybe in 2024, we might actually start to see that. I don’t know whether it’s Bernie or whether it’s AOC or someone else emerges.

But is that the way you think that this new party might develop? Because I don’t think it can just be created out of on-the-ground organizing in some evolutionary, gradual way, partly because there’s just no time for it given the climate crisis. Where there really has been traction has been in the Sanders type of candidacies.

What do you think? Is that sort of how a people’s party emerges?

Meagan Day

I think that that’s right. So, my contention would be that we’re more likely to get an independent left-wing, pro-worker party by going toe-to-toe inside of the Democratic Party and building up a devoted constituency that can see plain as day what the two sides are and suddenly develops a consciousness and a sense of commitment to one of those sides, our side. I mean, that’s how we’re going to get millions of people on our side, not by going off and starting our own thing and planting our flag and saying, Hey, do you like this? Come over here, even though nobody’s over here yet.

So, I think that picking fights within the Democratic Party is more likely to produce the result that we want than simply making what we would call a clean break as opposed to a dirty break and leaving right now to develop an independent party. And I also think it’s more likely that we’re going to get what we want by picking fights in the Democratic Party and building a constituency that way, and inviting the push-back from the capitalist elements of the Democratic Party. I think it’s more likely that’s going to happen than that the capitalist elements will simply slink away once they see that we’re starting to become more popular.

I also don’t necessarily believe in the gradualist approach to taking over the Democratic Party. I think that it’s going to be through struggle, and it may at some point be cataclysmic. I have a hard time predicting what that’s going to look like. But I think that it’s not just going to be, Well, we’re going to wage a fight for the soul of the Democratic Party, and then, somehow, we’re going to win it. I think that probably it’s going to be a bitter, bloody and open battle between the different elements of the Democratic Party. That’s probably how we’re going to be able to convince people that they need to enter into a new type of formation whether within the Democratic Party or within and then leading outside of the Democratic Party.

There are a lot of different scenarios that we can entertain. Obviously, I don’t have a crystal ball, but we tried to get into this in the book. We have a section in the book on the “dirty break” and on the socialist strategy: the democratic road to socialism is the basic calling card of that strategy. I would recommend that people should read about it if they want to hear more about what we think is likely.

One thing I don’t think is likely, is that the capitalist class is going to abandon one of its two major political assets in the world, the Democratic Party. You may have heard this pithy quote from I believe it was one of Reagan’s speechwriters or advisers who called the Democratic Party history’s second-most enthusiastic party of capital. Well, I think the capitalist class is a bit too intelligent and self-interested to simply get their feelings hurt by the rise of someone like Sanders or AOC, by that wing of the party, and sort of say, Well, fine: you can have it. I think that they’re more intelligent than that. I think they probably want to keep a hold of the Democratic Party. So, I’d imagine the road to what we want is going to run through open conflict, I believe.

Paul Jay

I think you’re right. You wrote, “The Democratic Party is a fundamentally pro-capitalist institution, which is another way of saying the soul of the Democratic Party is fundamentally a pro-capitalist soul.” These people that talk about the Democratic Party going back to its roots and going back to being a workers’ party and all this—I mean, it never was such a thing. Even if FDR represented a more—I don’t know if you want to call it “more socially conscious”—or that he saw the necessity of a compromise with the working class in the United States and a more rational approach, if you want, to a more mitigated capitalism. But it was never anything but a pro-capitalist party.

But do you see a need for—because I do—and this is what I hoped would come out of the Sanders candidacy: an organization that’s like a popular front, which within it has a DSA. And maybe the DSA or something of the DSA is at its core.

But doesn’t there need to be something very broad that includes people who wouldn’t call themselves socialist but see the necessity for a rational approach to climate, a rational approach to inequality, and so on? And when I say rational, I mean the fact that some things that will actually work.

Meagan Day

Yeah, I think that this is something that the movement is trying to figure out in real time. So, during the Bernie Sanders campaign—I think I mentioned this when I was last on your podcast—there were five organizations, DSA being one of them. Sunrise Movement was another one of them. Let’s see if I can remember all of them. Mijente, which is an immigrant rights organization. Dream Defenders, which is a Black Lives Matter, criminal justice, and racial justice organization. And the last one, I don’t think it was Justice Democrats. I can’t remember all of them, but you’re starting to get the picture.

All of the other groups, I would say, are more progressive–you could classify them or typify them as progressive rather than democratic socialist organizations. DSA, in the context of the Bernie Sanders campaign, built connections with these groups in order to act in concert. You may remember when I think it was Pete Buttigieg suggested on the debate stage that Bernie Sanders was actually funded by secret Super PACs. He was referring to this constellation of progressive organizations and one socialist organization that had banded together to try to get him elected.

So that was a sign that these groups are capable of coming together and what I would say is a more popular front type formation. There are deliberations happening as I speak about what to do about the upcoming election. I can’t really speak on them because they’re happening at the level of our elected representatives inside of DSA. Whatever happens, it’s not going to contravene the decision that the membership made at last year’s convention to not officially endorse Joe Biden. There are various sorts of workarounds that people are proposing, anti-Trump building coalitions, and so on.

People are trying to figure out this stuff in real time. It’s very difficult because the politics of these organizations demand, on the one hand, that we are friendly, approachable, and open to coalitions with people who disagree with us. And on the other hand, the demand that the largest socialist organization in the United States in over half a century not liquidate its political identity just because it’s feeling some fire under its ass. So, we need to make sure that we are standing for the membership joined the organization for and the explicit, stated political beliefs of the organization. Which means not openly campaigning for a Joe Biden presidency, even if many members—and I would say a lot of members—of DSA plan to vote for Joe Biden, and many of them even plan to volunteer for Joe Biden.

So, we’re working this out in real time. I think that we will fare better on this question if there is a Joe Biden presidency because it will give us the opportunity to identify who on the very broad left has the same set of values with regards to placing pressure on the Joe Biden administration and to try to build a popular front with those people. It’s very difficult under a Trump presidency because everyone from what would globally be called the center-right, all the way to the far, far left, despises Donald Trump. So, it’s hard to distinguish and to build a shared program and find your allies.

So, I think we’re all hoping for a Joe Biden presidency for that reason, among others. Yes, but I agree with you that coalitions are really critical.

Paul Jay

Yeah, I’ve been using the phrase—because I get flak in the comments section on the different podcasts: Why are you sounding like you want people to vote for Biden? The phrase I’ve been using is, We should choose our field of battle. Biden is simply a better field of battle than what would come from Trump, which would be I think an outright repression that maybe we haven’t seen certainly since the House of Un-American Activities Committee and McCarthy. I think it would be worse even than that.

But that being said, the Democratic Party—let’s assume Biden does win, and I think there’s going to be some shenanigans along the way from Trump and so on.

It’s kind of a paradox, to use that word again. There needs to be a struggle in the party against corporate Democrats and a fight to push actual progressive policies rather than smoke-and-mirror policies that sound effective but in fact aren’t. On the other hand, there’s going to have to be some alliances with some sections of the elites that get the threat of climate. Even if they don’t get anything else, they do see that there needs to be a real climate policy.

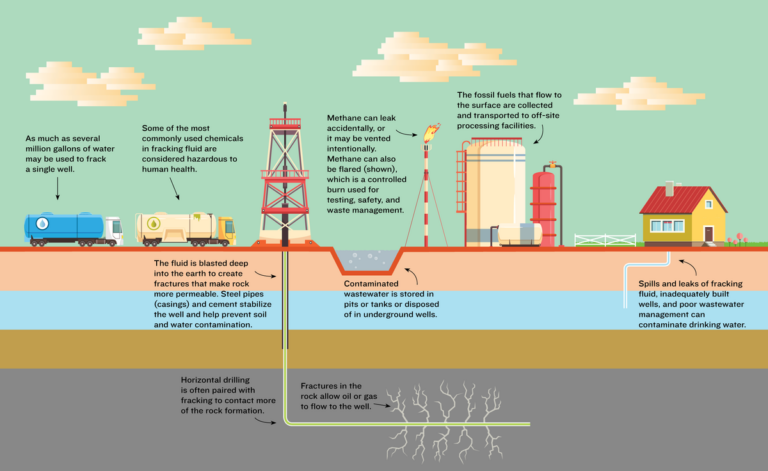

I interviewed Bob Pollin a while ago, the progressive economist, and we were looking at Biden’s website and his climate plan. It all comes down to carbon capture. The whole plan is based on the idea that these targets that they’ve set for getting carbon-neutral are going to be achieved through carbon capture. And right now, carbon capture is quite an unproven technology. There’s nothing in the plan for phasing out fossil fuel. In fact, if you read the plan, on the face of it, fossil fuel stays around because carbon capture works, and you don’t have to worry about phasing it out.

So, there’s got to be people in the elites who get that that doesn’t work and the threat is real. There’s going to have to be alliances with sections of the elites. Frankly, given the time frame of the climate crisis—which is, they’re saying less than a decade not to hit 1.5 degrees warming. Well, we are going to hit 1.5. We’re probably talking a decade or decade and a half not to hit two, nevermind 1.5.

So, we’re at a very critical point already. And frankly, the people’s movement, the workers’ movement, it ain’t strong enough to do something that effective in that time frame, which means some sections of the elites have to be brought into some kind of an alliance to get real about climate instead of the B.S. that we’re hearing. At the same time, this fight is taking place in the Democratic Party, where some of these sections of the elites might fight on climate.

I’ll give you one very specific issue that I think we all have to think about. I asked Tom Ferguson, who does a lot of work on politics and money, and so on. He knows a lot of people on Wall Street. I said if the elites, the financial elites had a choice between Sanders or, say, even a Warren, or a Trump, and they understand Trump represents a fascist-ization of the American state and culture, who would they pick?

And his answer was, well, if the wealth tax is still on the table with Warren and Sanders, they’re going with Trump. They’ll go with fascism. I think we’re going to have to take that seriously in the sense that some of the demands which need to be made. And the socialist perspective can’t be given up on—I take your point about DSA; it shouldn’t just become some amorphous front. In fact, even more overtly socialist and certainly not less.

But there’s got to be some way, and strategically, to make some of these decisions. There may have to be real compromises with certain sections of the elites to get them to back real climate policy.

Meagan Day

Yeah, I think climate policy is unique in the sense that it has this ticking clock to it. I am also persuaded by the alternative idea. I mean, I take your point that the workers’ movement is not strong enough to pull it off at the moment. Let me put it this way: it seemed that after the Berlin Wall fell and Francis Fukuyama announced that history is over, we’ve reached the end of history. Well, it feels to me that history has come roaring back to life in the last five years , and that things are bound to change very quickly. And so, I don’t think that we can write off the possibility that the worker’s movement is about to leap into action if we actually make a concerted effort to build it.

Starting in 2011, there’s just been an incredible appetite for change on the level of the working class in the United States. It competes with a deep, pervasive demoralization and demobilization, as well as outright repression, of working-class political activity. But things change quickly. History happens quickly.

And the best possible scenario, and the one that we should keep the door open to, is that we are able to force real climate action through the use of the best tool that people who believe in equality and justice and humanity have always had at our disposal, which is the ability to get our hands on the thing the elites care about the most. The thing that elites care about more than anything else is profits. Well, profits are actually, for the most part, generated by labor. And labor is done by people—people with minds and hearts, people who can be appealed to, which means that people can stop producing labor, they can withhold their labor, and that can hold hostage profits, which can extract concessions from the ruling class. This is the best possible way for us to go about actually forcing real action on climate.

The question is whether or not we think that we are poised to be able to do that within the time frame that is necessary.

Paul Jay

You’re talking about strikes?

Meagan Day

Absolutely. I’m talking about strikes. I somehow managed to not say the word “strike.” [Laughter.] Yes, I’m talking about strikes. I thought that perhaps I had said it. Yes, I’m talking about strikes. I’m talking about being able to build working-class power and consciousness to the point where people can actually withhold their labor and go on strike and say, We’re not going back to work. We’re not giving you your profits, the only thing you care about, until you take us seriously.

Paul Jay

I think this is a really important point because I think there’s a serious underestimation of the potential power of unionized workers in the United States. It’s always being talked about: all unions are getting so weak. The number of workers and unions has gone down. They call it “union density.”

But the thing is, where workers are organized is very strategic. It’s in transportation. It’s in tech. It’s in government. That one- day strike a few months ago, when the longshoremen on the West Coast closed down all the ports for a day in support of Black Lives Matter, which is a political one-day strike, it’s a real vision of what could be possible.

Meagan Day

There’s no question that union density is dismal compared to its peak in the United States, which was never high enough. I think the peak union density in the United States has probably been 30 percent, a little over 33 percent in the 1950s. We’re at ten percent now; ten is bad. We should feel concerned that it’s at ten.

But we should also understand that 30 percent was enough to dramatically change—it wasn’t enough to replace capitalism with socialism—but it was enough to dramatically change the landscape. It yielded the “great compression” of the mid 20th century, which is when there were high marginal tax rates, and there was a decent standard of living for most working-class people, at least compared to periods before and after.

Between ten percent union density and 30 percent union density—there’s not that much standing in the way of it. That doesn’t mean it’s going to be easy. It just means that it is completely possible for us to actually build union density back up. It just requires a movement that takes that task seriously. And I think that we see the emergence of such a movement.

It started in 2011—I mean, I think essentially the 2008 crisis represented the end of the suspension of disbelief in neoliberalism’s promises. Do you know what I mean? People started to not believe the very seductive fantasies that they had been told about: if you simply relent, if you stop resisting, if you abandon politics, there will be shared prosperity. The inexorable march of capitalist dominance actually also represents a march into a future of shared prosperity.

I think that stopped making sense to people in 2008. I think that in 2011, you started to see people agitating—not, I would say, in ways that were particularly strategic, but in ways that indicated that there was a deep well of feeling that we could tap into. Well, if we’re successful—and obviously, you know, you go on, you have the Black Lives Matter, and you have the two Sanders campaigns, you have the teachers’ strike wave of 2018, the largest strike wave in 48 years in the United States.

It seems that we do potentially have the raw material to be able to mount a new offensive for our side that could rebuild union density back up to the point where it would make sense for us to be relying on organized labor instead of relying on sections of the capitalist elite to get what we want. Now, I can’t say with great certainty that we’re going to be able to achieve this in the amount of time that is necessary for us to address climate change. But I do think it’s important for us to hold out the possibility and not throw in the towel too early.

Paul Jay

Yeah, I think there’s got to be a parallel strategy here. You’re right. You never know. These moments come, and all of a sudden, a mass movement emerges, and maybe we’re on the verge of one because of the pandemic, the depression, the deepening unemployment that’s coming.

Meagan Day

You know, people said in the ‘20s that after a great explosion of labor activity in the 1910s, much of which was actually not unionized and which gave rise to organized labor, the ‘20s were a tough period for unions. They thought, well, we had a nice upsurge. It seems like we set up a lot of these institutions, but things seem pretty quiet, and they don’t seem to be going in our favor. I mean, this is with the roaring twenties for the capitalist class, but it wasn’t great for organized labor.

The depression happened. You know, I won’t tell you the whole history. I’m sure you know it yourself. But by the time the 1930s and the 1940s rolled around, it was, like, there were massive sit-down strikes. There was incredible union militancy. I mean, these things kind of changed on a dime. A lot of it had to do with the combination of objective macro political-economic trends, which nobody has any control over, and people really can’t quite foresee, at least not with great precision. The combination of that, and having true believers who were committed to holding open the possibility that something like that could happen, who were painstakingly trying to build organizations even in the dark times, even in the bleak times, in the hopes that they would be vessels that could spring into action, that could be vehicles for working-class militancy and struggle if the conditions were right for it. Eventually, they were right for it.

Now, not right enough to replace capitalism with socialism. But I think our fortunes can change quickly. So, we need to be behaving as though they might so that we can take advantage of them if they do.

Paul Jay

And people shouldn’t be disappointed, especially in the United States, that this doesn’t right away—or even in the short term, medium term—become quote-on-quote-socialism.

You can’t forget: the United States is the empire. And in the heart of the empire, some of the things that might be possible in other countries aren’t going to be possible, if for no other reason than that the American elites have endless amounts of resources to throw money at the working class in the United States if it’s necessary. You can see it from the pandemic: all of a sudden, there were trillions of dollars. I know most of it went to the elites, but a lot of it did go to payments to workers. If there’s a Biden administration, they will provide some kind of funding. If the situation gets really sharp politically for them, they’ll find ways to throw resources at it.

So, I mean, Americans have to be realistic about what can be done. (And I don’t want to get into this now; it’s another conversation.) But especially there should be more focus on mitigating U.S. foreign policy. It should be a real priority for the American progressive movement, and it doesn’t get talked about, generally speaking, enough.

But we only have a little bit of time left. I want to raise one other issue with you, which is, in the book, you talk about you being radically transformed by the Sanders campaign. Meagan became a socialist during the Sanders campaign. So how did all this evolve for you?

Meagan Day

Well, I think I had existed on the broad left for about a decade before Bernie Sanders’ first campaign. But I understood what socialism was. And I was fairly certain that morally and ethically, I was on the side of socialism, abstractly speaking. But I just had never been asked directly the pointed question, Are you a socialist? Because I didn’t know, you know?

Paul Jay

Well, had you encountered Marx and Engels?

Meagan Day

I mean, barely. I had a political education that was post-Marxist. I went to an expensive liberal arts college. I think most of the time when I encountered Marx, it was mostly in the context of reading theory that was post-Marxist that had moved on from the old left, and which was inspired by instead the new left. And so, no, I mean, I hadn’t, really.

I think that what happened for me in 2015 was that a sort of latent understanding that was already there. I will say, to be entirely transparent, I didn’t grow up in a working-class household. I grew up in a relatively wealthy household. For me, actually, that brought into great relief—into sharp relief—the extent to which class and capital shape the opportunities that are available to an individual person in the world.

So, this seems quite obvious to me based on my own experience. When Occupy Wall Street happened, I remember thinking the 99 percent and the 1 percent is a great framing. I think that it’s pretty excellent. It pretty much cuts to the point. And when Bernie Sanders started talking about democratic socialism, it just tapped into something that was already there, an awareness or an understanding that was already there: that the dividing line in society is between people who own capital and own what I later learned were called the means of production and those who have to sell their labor to those people for a wage in order to buy the basic necessities that they need to sustain themselves in order to survive.

That is an axis on which much of society hinges, and it’s an axis on which our strategy for achieving a better world should also hinge. Which led me very quickly down the road of reading everything I possibly could about socialism: reading primary sources, reading Marx and Engels, but also reading lots of secondary sources and learning about the history of socialist struggle and working-class struggle.

A lot of that was done in the context of the Democratic Socialists of America. I was a part of that first wave of people who joined DSA right after Bernie’s primary was over. I think I joined a month before the general election in 2016 because I had seen enough and I had read enough, even just in the space of a few months, in the first Bernie Sanders campaign, to know that if there was a socialist organization out there, I should probably be a part of it. Because whatever Hillary Clinton in the Democratic Party and the Democratic Party donors were pushing back on that Bernie Sanders was offering needed to be augmented for the long haul and needed to not be restricted to one person, Bernie Sanders. I felt very much ignited. Like, I wanted to be a part of the socialist movement. So, I went, and I sought it out, and I found DSA. I did a lot of political education in DSA. So that’s the sort of general story of how I got involved in DSA.

Now, my story is not the same as every other person in DSA. For one thing, a lot of people in DSA don’t come from wealthy class backgrounds like me. I don’t think that people come from poor class backgrounds, either. A lot of times, we joke that in DSA, we have a lot of downwardly mobile, middle-class millennials. I don’t think it’s anything to be ashamed of. I think it’s actually the section of the working class who’s becoming turned on to socialism right now. Every revolution in history has seen one section of the working class or another lead the charge for reasons that are sort of beyond people’s choosing and, in many cases, beyond their comprehension. So, in DSA, I think that’s the primary demographic, though I do believe the organization is rooting itself more and more in the working class through concerted effort.

Paul Jay

OK, well, I know you don’t like talking about yourself a lot, but I’m going to try to get you to do it again in another podcast. We’re kind of out of time now. [Laughing.]

Meagan Day

All right. [Laughing.]

Paul Jay

But I actually think it’s important. I’ve done this series called “Reality Asserts Itself,” and I’ve done many interviews with all kinds of people. A lot of these interviews are about people’s political evolution. The kind of people that didgrow up in families that were often—like Larry Wilkerson, for example, or Ambassador Joe Wilson—grew up in kind of conservative Americana families, grew up believing in the Cold War, that generation, and then broke from it. I think it’s a very important thing for people to understand the process because we all grow up with a set of preconceived notions that come from our families and schools and the culture. Breaking with that is a critical part of a process of, I think, seeing the world as it is.

It’s also a very important part of the process of what I think this pandemic’s doing, which is, it’s creating a moment where, to use the name of my show, reality is asserting itself. There’s this great phrase, and I don’t know who coined it, but I always thought it was so good: at certain moments of history, people lose their ideological moorings. We’re in that moment. A lot of people are losing their ideological moorings. And the comfortable answers that came from the status-quo political culture are all shattering.

It’s at these kinds of moments [in history]—you’ve had, one, the rise of the important religious movements, including Christianity, but also the rise of fascism or the rise of a really progressive movement. So, we’re at such a critical moment. I think it helps for people to hear the stories of people that have broken with the way they were brought up. Because so many people are asking these questions and going through this process right now.

Meagan Day

Sure, and I guess I will say something to this effect. I think this is an interesting topic of conversation. I’d be glad to come back on and talk about it in greater depth.

But I think when people first become socialists, I’ve noticed—and many people are becoming socialists for the first time right now in the United States, so you get to see this happen in real time. I think there is a sense in which people assume that socialism is the natural ideology of the working class. All we have to do is clear the obstacles for people to be able to access it.

But insofar as I was raised in a non-working-class household, I had to do a great deal of ideological dismantling in order to get to the point where I was convinced of socialism and of the necessity for a socialist and working-class movement. But it’s also true that working-class people, I think, also have to do that kind of dismantling because whatever sort of ideologies I had been privy to, there are inverse ideologies in which the working class is steeped. These are demoralizing and demobilizing ideologies that also need to be cast off.

So, nobody is sort of automatically a candidate for socialism. Socialism, of course, describes the movement of the working class, but a political ideology does not flow automatically from class location. There’s a process of class consciousness that has to be undergone. That involves, as you said, I like this way of thinking about, becoming ideologically unmoored, which, of course, macro-political circumstances are very good at doing. I think you might be right that we’re in one such moment.

Hopefully, many working-class people become unmoored in a way that makes them primed for socialism. And hopefully, many socialists are doing a good enough job reaching those people that we can actually see some people come to our ideology instead.

Paul Jay

I mean, how many workers volunteer to go fight in wars where they sacrifice their lives to defend the society we’ve been describing? This unequal society, so no doubt: the working class doesn’t naturally go in this direction when all the instruments of culture and schooling and movies and everything else are so weighted the other way.

Anyway, let’s do it again. Thanks very much for joining us.

Meagan Day

Thanks, Paul. I really appreciate it. And I’m happy to come back on whenever.

Paul Jay

Great. Thank you for joining us on theAnalysis.news podcast.

Please don’t forget there’s a donate button at the top of the page on the website. If you’re listening on one of the many podcast platforms, I don’t think there’s any way to donate on those platforms. So, you’ve got to come on over to the website to do it. But thanks for listening.