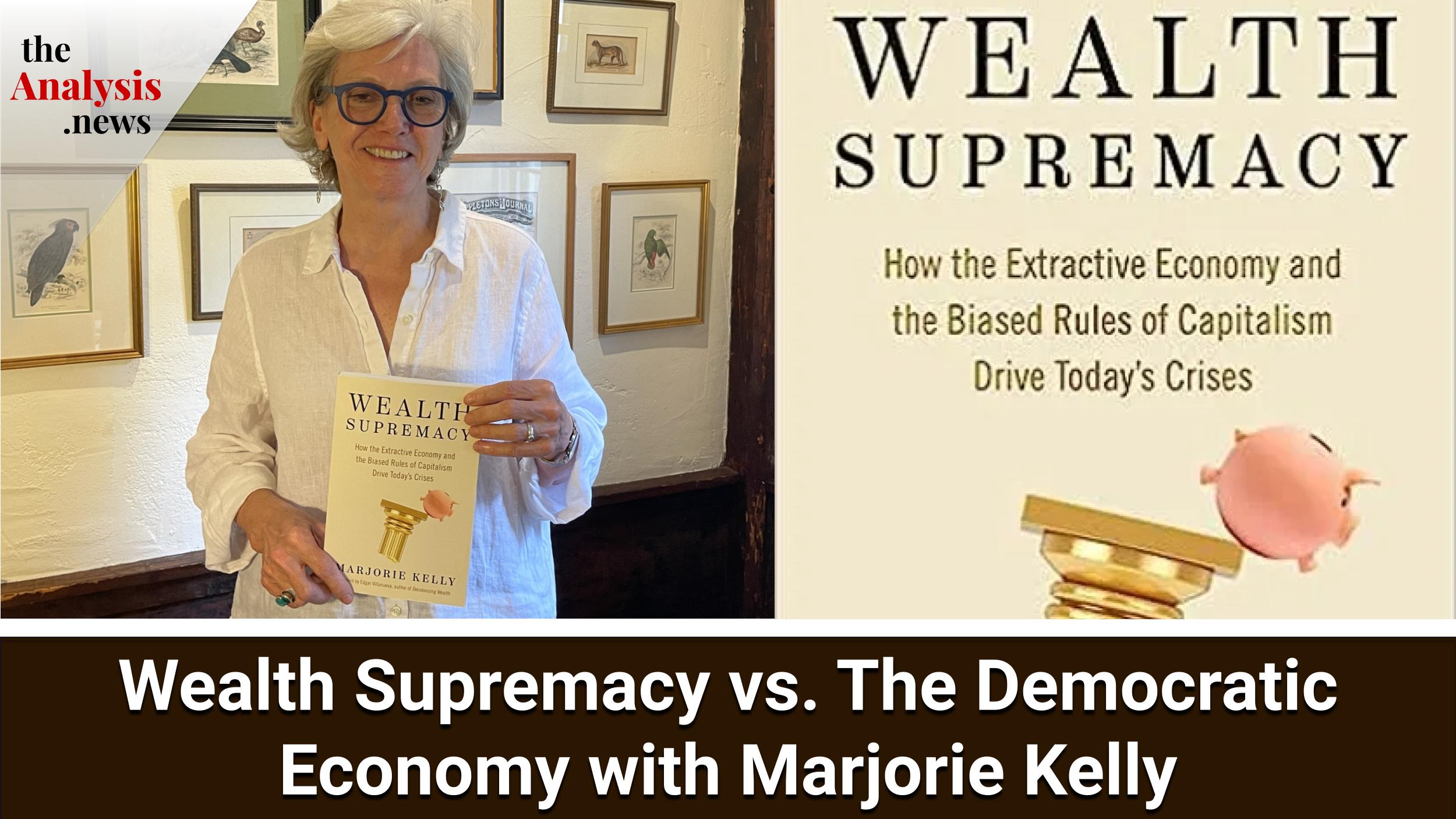

Renowned social theorist, systems thinker, and organizer, Marjorie Kelly, gives an early look at her new book: Wealth Supremacy. Speaking with Colin Bruce Anthes, she details the entrenched ways our current system is built around myths that make giving more wealth to the already wealthy seem necessary— even when we try to use our institutions for the common good. Kelly contrasts this with an outnumbered but successful democratic economy with many forms of democratized ownership and participation: public utilities, employee-owned companies, community land trusts, cooperatives, and more. We can create an economy that works for everyone, she argues, but only if we systematically discredit the moral status of wealth supremacy and turn towards a democratic economy paradigm.

Colin Bruce Anthes

Welcome to theAnalysis. I’m Colin Bruce Anthes. In a minute, we’ll be speaking with the renowned social theorist and organizer Marjorie Kelly on her new book about wealth supremacy and its democratic economy alternatives. Please remember to like, subscribe, ring that bell so you get notifications, and consider hitting the donate button to support our work. Stay tuned.

It’s been 15 years since the financial crash that brought the global economy into the biggest recession since the Great Depression. Despite steady outrage across the political spectrum, inequality, and concentration of ownership, the financialization of assets continues to skyrocket. According to the new book by Marjorie Kelly, that won’t change until we address the system-wide problem of wealth supremacy and begin bringing democratic forms of ownership and participation to every aspect of the economy. The good news is many of the alternatives already exist, are functioning well at a smaller scale, and are ready for prime time.

Marjorie Kelly’s own story and evolving career have included co-founding Business Ethics magazine in the 1980s, inspiring the creation of the B Corporation, and co-founding Fifty by Fifty, which seeks to see employee ownership reach 50 million American workers by the year 2050. She is a distinguished senior fellow at the Democracy Collaborative. Marjorie Kelly, welcome.

Marjorie Kelly

Thanks for having me, Colin.

Colin Bruce Anthes

Can we begin by contextualizing how you came to write this book because, in many ways, you’re one of the original canaries in the coal mine regarding what we might call “friendly capitalism.” You come from a business family, you worked at Business Ethics magazine for 20 years, you handed out Business Ethics awards, and you had quite a name for yourself there. Yet, you end up concluding, and I quote from the book, “Moral capitalism is as impossible as moral racism.” How do you end up at this point?

Marjorie Kelly

This book is a turning point for me, Colin. I have spent more than 30 years writing about and advocating the positive. I know so many progressive business leaders, socially responsible investing these days called impact investing or ESG [Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance]. I’ve tracked these fields really since their infancy. Community wealth building is a new form of economic development that the Democracy Collaborative is advancing, and it’s catching on really widely. There’s so much happening. There are so many visionaries building out the positive. That’s what I’ve wanted to focus on. But I’ve become discouraged.

I see now that we’re losing ground faster than we’re gaining it. The reason is that we have yet to turn and morally discredit the existing system and its core value, which is wealth supremacy. We really live inside an economic system designed to make the wealthy wealthier. That’s not hand-waving.

I’ve been like a spy inside of business for a couple of decades. I ran a small company for 20 years, and I sold my dad’s business after he died. I know how business works. I’ve lectured at a lot of business schools. What I can see and what I do for the reader is to unpack the granular ways that the system is rigged.

We have this sense the system is rigged against us. It is in very specific ways. I call them seven myths. They really form the operating system of capitalism, which we accept is normal. It’s taught in business schools. It’s the fundamental corporate governance structure and investing aims. I mean, it’s really built in. This wealth supremacy is built in all over. Until we turn and challenge that, I think our efforts are going to fail.

Colin Bruce Anthes

Let’s get to the quick and dirty definition of wealth supremacy because it sounds like a concentration of capital. Of course, every day in the news, there’s something about terrible billionaires, and people are familiar with the huge amount of inequality that we see. But wealth supremacy, as you’re alluding to there, actually goes a little deeper. It goes into the quasi-invisible infrastructure of the system.

Marjorie Kelly

Yes, that’s right. I use two terms: wealth supremacy and capital bias. Wealth supremacy is the cultural ethos that admires wealthy people and empowers them. Wealthy people have power in philanthropy. There’s a power over government to political donations, and corporations are seen as the property of shareholders rather than as human communities, which is what they are. There are so many ways that our culture valorizes wealth.

Then, there are the very specific ways that wealth has power inside the economy. This is what I call capital bias. In corporate governance, only shareholders vote. Workers are not considered members of the corporation, which is odd. It’s very much like women at one time who were not considered members of society. You accept this as a norm. The income statement, which every corporation uses to guide its activity, says to pay capital as much as possible. That’s called profit. It’s good. Drive it up. Pay workers as little as possible. That’s called expense, and you need to drive it down. There are various ways that are built into the structure of power in our economy; it favors capital and disfavors workers, the community, and the environment.

Colin Bruce Anthes

That’s a very important point because it speaks to how quickly things that we know can become invisible. We all know that workers tend to get shafted by the economy. Most of us have experienced being the workers getting shafted. Yet when I am working at a company, I am, of course, thinking of myself as a contributor, not an expense. At the same time, that’s not the way the company is organized.

Marjorie Kelly

Yes. How we think of this as a corporation, as an object owned by shareholders, that has consequences. For example, when the big tech firms hit a downturn in their stock price a little bit ago, the first thing that they did was throw thousands of workers out of their jobs. This is so standard. What they were doing is they were saying, “Okay, our share price is down. Share price is related to your profit, so you need to boost your profit; that means you need to cut your expenses.” They’re basically transferring income from labor to capital very deliberately, and it’s very, very common. We just accept this as normal.

Colin Bruce Anthes

One of the examples that you give in the book that’s really concrete and shows how deep and how invisible the roots of wealth supremacy can be is Harvard College and Harvard University. One might think at first glance that Harvard is a registered charity, producing some of the best post-secondary education in the world, certainly in the United States. What could be wrong with that?

Marjorie Kelly

Harvard is about… 66-67% of its endowment is invested in private equity and hedge funds. These are the predatory bleeding edge of capitalism right now. When we try to regulate capitalism or enforce change, it flows around whatever barriers we put in place.

When there were Superfund laws saying you can’t dump toxic chemicals in waters, well, what did the chemical companies do? They moved to China. They’re like, “Fine, we’ll dump in the waters off of China.”

What’s happening here? There have been a number of investors who’ve said to the big oil companies, “You need to get rid of your dirty assets. You need to divest these dirty assets.” Some of the big oil companies have done this. But those assets, these dirty operations, are not going away. They’re being sold to private equity. What’s happening is they’re shifting into the shadows, and private equity, in some cases, is tripling production on these really dirty fossil fuel operations. Yet, private equity is opaque, it’s non-transparent, it’s non-accountable. I’m not even convinced that Harvard knows what’s going on inside the private equity funds that it’s investing in because what they’re focused on is the return. This is how the system… you could call it a willful blindness. You could call it an inadvertent blindness. But there’s a built-in blindness to the effects of what we’re doing.

Colin Bruce Anthes

Because some people are just being professionals, doing their job, making sure that the company or the organization gets what it’s supposed to get.

Marjorie Kelly

Yeah, that’s right. We have narratives that tell us this is seeking maximum returns for investors. That’s benign. That’s normal. That’s technically necessary. You have asset managers who are moving assets up the risk-return spectrum; that’s how they say it. We’re going from the public markets to the private markets. What they don’t say, what they don’t see is that we might be destroying jobs, we might be trashing the environment, and we might be capturing politics. That is what’s happening with corporations and private equity. But we don’t see that. We don’t see that on the investment statements that we receive from our money managers. We’re allowed to pretend that we have no role in that.

Colin Bruce Anthes

You also really sound the alarm on the urgency of this issue. Of course, a lot of things have been going wrong, especially over the last 15 years. But then you start painting some dystopian situations that are not science fiction. They’re already starting to happen, where we have these kinds of companies buying up water rights and talking about multi-trillion dollar natural resource industries that would be taken away from the general public.

Marjorie Kelly

Yes. Colin, one of the things I talk about in the book is financialization, the fact that there are economists who have warned us for decades that there’s too much financial wealth in the world in too few hands. The finance sphere of assets is now five times GDP. It used to be equal to GDP back in the 1950s when I was a kid. But this sphere has to keep growing and growing and growing. So it has to go out, basically, colonize new kinds. They call them new asset classes. We talk about it in a very technical, benign way, but it’s really a colonizing force.

What big capital is colonizing now is they call it ecosystem services and water. Water rights are a big part of that. Hedge funds are right now out in Colorado and California buying water rights because they know that water shortages are looming. The UN warns that by mid-century, half of the population of the globe will be suffering shortages of water.

Now, some of us might look at that as a humanitarian crisis. Capital looks at it as an opportunity to own and extract wealth, and that’s exactly what they’re going to do. It’s not just water, it’s also coral reefs, forests, and farms. There’s this capital, and unless we see it and stop it and are alarmed about it, it’s going to own the foundations of life itself.

Colin Bruce Anthes

Let’s get to your second paradigm and start putting a little bit of contrast to wealth supremacy, which also sometimes helps us to see it better when we can start to see alternatives function.

Marjorie Kelly

Yes. This is what I love to talk about because this is what I’ve been working on, and what the Democracy Collaborative is working on is how else would you design an economy, a modern, sophisticated economy? What would that look like?

Well, for example, worker-owned firms. You mentioned that I was working to advance worker ownership. We helped to create the Fund for Employee Ownership in the Cleveland cooperatives, which is three worker-owned co-ops, like a big commercial laundry that’s entirely owned by its workers. Many of them are formerly incarcerated people of color right there in the inner city of Cleveland, and they’re supported by large anchor institutions like Cleveland Clinic. They’re doing all the laundry. It’s an example of you’re starting to build a different system. Anchors want to buy locally, and workers can own companies, and those workers are getting bonuses of $8,000-$11,000 at the end of the year. Worker ownership, that’s one model.

Water, we can talk about it. We don’t have to let capital buy the water rights– 85% of Americans now get their water from municipally-owned utilities. We’re taught to fear public ownership. We’re told, “Oh, that’s communism. That’s inefficient.” All the things that we’re told. In the same way that we used to be told that women were hysterical and so forth, or that black people are inferior, we’re told that the democratic economy models are inferior, and they’re not. Water, when it’s municipally owned, evidence shows that you get better service at lower rates. The same is true of electricity.

Right now in Maine, they’re coming up on an election to see if they want to get rid of these investor-owned electric utilities in the state and have the people vote in. No, we want to have representatives of the people govern the electricity of our state. These are ways that we can begin to take back our economy from the 1%.

Colin Bruce Anthes

What about things like land and finance? Are we able to democratize those aspects of the economy as well?

Marjorie Kelly

Yes, absolutely. I talk in the book about black-owned farms. There used to be a million black-owned farms in America, and today there are about 40,000. Even those are struggling because Big Ag[riculture] has moved in and pushed out so many family farms. Biden tried to forgive the debt held by black farmers, and there was a Trump front group that pretended to be white farmers, but it was really a Trump front group that sued to stop this. There’s some relief coming their way. Farmers ought to own their land. Investors should not be participating in a land grab.

Local ownership of land. There are community land trusts where the community owns the land and individuals own the houses on top of it; that keeps houses out of the speculative market. In the 2008 downturn, houses in community land trusts had one-tenth the foreclosure rate of traditionally owned homes. These are just a couple of the models of how we need land, housing, water, enterprise, banking, and finance. All of these are models. We have proof of concept that these things can work; impact investing is growing dramatically right now. These are investors saying, “We want to help solve racial inequality. We want to help advance the green energy transition.” They’re using capital to do it. There are positive ways that this democratic economy is being built right now.

Colin Bruce Anthes

Those are wonderful outlets, and of course, I support them full-heartedly. There is the question of how we manage to fight back against the institutional forces of wealth supremacy that are very much moving in the opposite direction.

If I can localize that problem for myself, I live on the endowment lands of the University of British Columbia. In the Vancouver area, some of the enterprises that are doing the most good for the community and offering the most support are cooperatives. Vancity Credit Union is doing astonishing things. The Vancouver Renewable Energy Co-op is a major beacon of hope. The community land trusts, which you mentioned earlier, and housing cooperatives are some of the few sources of reprieve from the very severe housing crisis that we have in Canada right now. So we’re leaning on these outlets very, very heavily.

Yet, I also live next to the Sauder School of Business. Now, the Sauder School of Business is ranked the number one business school in Canada, and it also has a big center for business ethics. It’s reportedly a very ethically concerned institution. When I look at their course offerings, they have 140 courses on their course calendar. There’s one fourth-year course on social enterprise. There’s nothing on cooperative entrepreneurship and nothing on cooperative management. At the very same time that the surrounding community is leaning very heavily on cooperatives, the number one business school in Canada, which is located in that community, isn’t covering it.

Marjorie Kelly

That is such an interesting insight, Colin. Yes, when I was editor of Business Ethics, business people tended to be more progressive than business schools because business people live in the real world. They know that there are a variety of stakeholders they have to keep happy. Whereas business schools are holders of the ideology, and they hold tight to that ideology. What you’re pointing to is the fact that we’re talking about a new paradigm. There is a new paradigm emerging for business and investing for the economy that’s about, No, you can’t keep running an economy just to serve the 1%. We need an economy for all of us. It’s so obvious when you say it, and that needs to be built into the institutions and the practices of the economy. That’s the evolution that we’re talking about here. But business schools, I’m sad to say, are often the laggers. They’re teaching the old model. They’re teaching shareholder primacy, that the aim of management is to maximize returns to shareholders, which you can translate as make the wealthy wealthier and ignore everything else. Whoever you step on along the way, it’s not considered material. I’m saying it in a very bold way because I think we need to understand that that’s exactly how it is.

I would also add that most business schools do have professors who are advancing the new paradigm. They tend to be marginalized. I’m told by economists that they can’t get published in the really mainstream journals. I was told by one Harvard professor that he finally got permission to do a class on new economics and alternative economics. They gave him one caveat, which is that majors in economics cannot take the class.

Colin Bruce Anthes

As long as they’re not training economists.

Marjorie Kelly

Only the low peripheral people can take that looney stuff. But nonetheless, this new paradigm is advancing, and I think it’s unstoppable. I think business schools are not going to look good in the IEP history because what they’re teaching is about apartheid. They’re basically saying serving the wealthy is our aim, and whatever is done to advance that is okay.

Colin Bruce Anthes

You mentioned many pieces that are promising, and I shouldn’t say promising, they’re functioning very well. As you mentioned, things like community land trusts, various kinds of cooperatives, and employee-owned companies have very good success rates, as well as more humanitarian purposes and more democracy. You also mentioned community wealth building, which sees some of these pieces coming together to support each other and create a bit of an amplification effect. That’s very important, too, because we need to accelerate these activities to be able to start dealing with problems at scale. How do we get above the noise? Make sure things like municipal governments, which could also be amplifying the wealth supremacy paradigm and often are, are moving into this paradigm and helping to bring those elements together, supporting a move towards a democratic economy paradigm. Are there examples of communities that have succeeded in doing this that we can turn to?

Marjorie Kelly

There are Colin. There are places that are successful at this, and mayors are interested. At the city level, people know their communities are in trouble. Mayors don’t live in an ideological world like a business school does. They live in a real community. If their communities are in trouble there, they know something different needs to happen.

Marjorie Kelly

Our former President, Ted Howard, he and I co-authored The Making of a Democratic Economy. He’s right now in Amsterdam, and he has a couple of-year contract to work on building community wealth in an immigrant neighborhood there. There’s a pretty large project happening there.

Neil McInroy, one of my colleagues at the Democracy Collaborative, he has been an advisor to the government of Scotland, and Scotland has taken a whole nation approach to community wealth-building. There was a leading county there that showed you can do community wealth building successfully. Now, every county in the country is doing a community wealth-building plan.

In community wealth building, there are various pillars. It’s about land, housing, enterprise, good jobs, local investing, and all of these things as a way to keep wealth local, keep it circulating, and have wealth in broad-based hands. Community wealth building is basically the idea of transforming communities by having ownership and control of their own assets.

We inspired some work and participated a bit with some work in an England community, Preston, England, which was a Rust Belt community, and it still is to some extent, but their city council took up community wealth building. They actually moved the needle on unemployment and poverty in that city to the extent that it was recently named the best place to raise a family in the United Kingdom. Community wealth building, our staff working in this can’t keep up with all of the demand for cities wanting to do this. It’s the democratic economy being built at the local level. It’s pretty exciting.

Colin Bruce Anthes

Very, very exciting stuff, especially since these are replicable methodologies. There is still the question. I’m glad that we get a chance to profile it here, but those municipalities do need to be able to get above the noise in order for the other municipalities to know about those successful projects and adapt to those methodologies. Do we not also need the larger, bigger-name politicians, the state leaders, and the national leaders to be talking about this stuff as well to make sure it’s on everybody’s radar?

Marjorie Kelly

We do, absolutely. I’m happy to say that Biden put community wealth-building into his economic development strategy. We were thrilled to see that. I’ll say the governor of Colorado has made employee ownership a real priority and is developing a lot of avenues for advancing that at the state level. There are something like 16 centers for employee ownership around the country, one in each state. There is work happening.

The thing that I see, Colin, is that it’s not enough to build the positive. We’re not going to get there by just scaling up cooperatives or scaling up impact investing. We need to do that, but that’s not the sole essence of transformation. We also need to turn and discredit and stop the financial extraction. I do believe, and my hope is, that wealth supremacy and capital bias might serve as a unifying name for the problem. Then that tells us, well, what’s the unifying name for the alternatives? But we need to begin seeing this work as unified and as a system change alternative. We’re not quite there yet.

Let me give you one example. Our CEO, Stephanie McHenry, was formerly the President of ShoreBank, Cleveland. You might be aware of the institution in the U.S. called community development financial institutions; that’s a terrible name. It’s very long—the CDFIs. There are 1,000 of these around the country. The very first model was ShoreBank. This is a bank in Chicago, and they had a sister bank in Cleveland that existed to make good loans in disadvantaged communities, and they figured out how to do that as a profit-making bank. Profit making, but not profit maximizing. Stephanie’s bank was making good loans in Cleveland’s disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Leading up to 2008, big capital moved in and started putting predatory mortgages on these homes, particularly pushing these onto black families who might have qualified for traditional loans, and virtually ruined and melted down the global economy in the process. Along the way, ShoreBank was destroyed. It was devastated in the 2008 downturn.

It’s an example of how we can build positive, but then predatory capital will come and devour it. I’ve seen this. We used to have so many community banks in this country, and now they got devoured and turned into big banks. I was involved with consumer co-ops in the U.S., and they basically invented organic food or marketed it, creating a market for organic food. Co-ops don’t control organic food anymore. What we build will be devoured until we turn and start to take on the idea of the system as it is.

Colin Bruce Anthes

It’s a sobering point, but it’s a realistic one. We can build viable alternatives, but will they actually be able to take up space? Not unless we’re calling out the problem at every stop.

Marjorie Kelly

That’s right. And stopping the extraction, which is working in the opposite direction and which is so much larger than our little positive experiments.

Colin Bruce Anthes

Do you think the central challenge that we face, and something that you do speak of a bit in the book, is the speed of big money? It’s hard when we’re building up, say, cooperative movements, which usually begin with some people scraping together their nickels and dimes to start a local credit union and then one loan at a time building up. Good stuff, great work often really benefits a community, but it is much slower than the rate of big money.

Marjorie Kelly

People like you and me, Colin, we want to focus on the positive. We’re positive people. We want to build a better economy. We don’t want to be naysayers or tearing down capitalism. I’ve never wanted to be that. But I’ve come to see that what we need to tear down is not capitalism. This is an economy. You don’t want to tear down an economy. We rely on it. But what we need to take apart is the idea at the heart of it, which is that economies exist to maximize returns for capital. That’s what business schools are teaching. That’s the premise of investing. That’s the premise of corporate governance. That’s the idea we need to take on and discredit; that’s why I call it wealth supremacy because we know that white supremacy is discredited and morally invalid. We need to recognize that wealth supremacy is morally invalid, and yet it’s everywhere.

Taking on that idea is different. We’re not attacking individuals. We’re not tearing down anything, and we’re recognizing that idea has become outmoded. What I’m hoping is that this can begin to penetrate the idea that our capitalism is inevitable, it will never change. There are many people who believe that it’s easier to imagine the end of life on Earth than it is to imagine the end of capitalism. There’s this imaginative impossibility that captures us and prevents us from hope and from unified action. I think that’s what we need to penetrate and to change.

Colin Bruce Anthes

That would be a great closing note. I want to go into one more subject if that’s okay. Which is one potential area that pertains to, if we think about a different paradigm, there is a very sizable opportunity. That is something that is currently a big problem, which is what’s called the Silver Tsunami, this cascade of retiring, baby boomer entrepreneurs. In Canada, and I’m sure it’s about 10 times larger in the United States, but in Canada, the Legacy Leadership Lab has estimated that there are 700,000 small and mid-sized businesses at risk of closing because of a lack of secession planning among these retiring entrepreneurs in the coming years. I know a part of the employee ownership fund that you mentioned at the beginning of this interview was about changing some of the work in Cleveland, which was initially very focused on starting new worker cooperatives from scratch and we save these existing, often community pillars in Cleveland by helping the workers purchase those companies.

Marjorie Kelly

Yes. Thank you for bringing that up because that is a tremendous historic opportunity that there is this transition of baby boomer entrepreneurs, and most small businesses close. A few will be sold to competitors, and a few will be sold to private equity. We have an opportunity to say, “No, let’s sell them to workers.” There are financing mechanisms. Workers don’t need to come up with the capital. There are ways to finance it. We could have a huge wave of worker ownership coming. Actually, capital has a role to play in it. You can have reasonable returns financing these kinds of transitions. There was a large Canadian pension fund that paid for the transition, the financial transition of Taylor Guitars. Workers will ultimately own that company and benefit from the wealth that they are helping to create, while the pension fund will get reliable long-term returns. Yes, Colin, this is a real opportunity for a transformational movement.

Colin Bruce Anthes

Marjorie Kelly, thank you so much for the time that you’ve given us today. I really encourage everybody to read this book. It’s a very readable, accessible book, and it’s full of very useful facts, but it’s all contextualized so well that you can also see the bigger picture while looking at those facts. I really recommend everybody go and pick up a copy of Wealth Supremacy, and let’s expand this democratic paradigm. Thank you so much, Marjorie.

Marjorie Kelly

Colin, thanks for having me. This was great fun.

Colin Bruce Anthes

Thank you for tuning in. If you’d like to support our work, you can go to the website, sign up for our newsletter, and consider hitting the donate button. Take care.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | TuneIn | Deezer | RSS

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter

Marjorie Kelly is a Distinguished Senior Fellow with The Democracy Collaborative and the author of Wealth Supremacy: How the Extractive Economy and the Biased Rules of Capitalism Drive Today’s Crises (Berrett-Kohler, September 2023). Her previous books include The Making of a Democratic Economy (co-authored with Ted Howard), Owning Our Future: The Emerging Ownership Revolution, and The Divine Right of Capital. Kelly has for years been a thought leader in next generation enterprise design, employee ownership, impact investing, and the building of a community-rooted democratic economy. Previously, she was a Fellow at the Tellus Institute and cofounder/president of Business Ethics magazine.