Iranians protest brutal repression and why U.S. statements of solidarity are empty without a reversal of crushing sanctions. Assal Rad joins Talia Baroncelli on theAnalysis.news.

Talia Baroncelli

Hi, I’m your guest host, Talia Baroncelli, in Berlin, and you’re listening to theAnalysis.news. I’ll be guest hosting a few episodes for theAnalysis. I’ll tend to be focusing on new migration issues, Iranian politics, as well as the contradictions of global capitalism. My political interests are shaped by my family history, as my mother and her family were advised to escape Iran during the Iranian revolution. My father’s side is primarily working class; Italians and Serbians. I grew up in Canada, but I’ve been living in Berlin for the past 12 years or so. I’ve been working at an NGO, working with refugees, primarily from Afghanistan, Syria, and Iran. I am now doing a Ph.D. in new border practices, the security regime, as well as the surveillance of asylum seekers. I’m currently working as a researcher at the University of Graz.

That is enough about me. Please don’t forget to donate by going to our website at theAnalysis.news and by signing up for our mailing list. In a few seconds, I’ll be joined by Assal Rad to speak about the ongoing protests in Iran.

I’m joined now by Assal Rad. She is a historian and the research director of the National Iranian American Council. She is the author of a recent book called The State of Resistance: Politics, Culture, and Identity in Modern Iran. Thanks so much for joining us, Assal.

Assal Rad

Thank you. Thank you for having me.

Talia Baroncelli

So on September 13, Mahsa Amini died in hospital after being beaten to death by the morality police, or at least allegedly being beaten in their custody. Since then, we’ve seen protests across Iran. We’ve also seen protests not just in urban centers but also in rural areas. I wanted to speak to you about the resentment on the part of the Iranian people towards the regime, as well as some of the socioeconomic factors which have undergirded the protest so far.

Assal Rad

Yes, of course. The first thing to– when we talk about what happened specifically to Mahsa Amini because I think there are so many layers of stories that are going on right now. Of course, it was ignited by this horrific event, by the killing of Mahsa Amini. The one thing I keep wanting to emphasize is that I think sometimes there are people– and I understand, it’s a [inaudible 00:01:51]. Eyewitnesses say that she was beaten by the morality police, the so-called morality police, in the back of the van. Iranian news media tries to release videos saying, “look, she was walking around.” The bottom line of it, regardless of whatever anybody comes up with, is she should never have been detained. She should never have been in the position where the positioning of her headscarf would be a reason to detain this young woman. Clearly, if she had not been detained, if she had not been harassed by the morality police, she would be alive today. This is clearly the responsibility of not just the individuals who detained her, but of a state that allows these types of draconian laws, that imposes these laws on its people, but also that allows violence against its civilians with impunity. A system that has no accountability for its officials when they carry out violence against their own people. What we are seeing in protests is indicative of that.

I wanted to put that out at the very beginning. Cross narratives don’t matter. She should never have been there. It is the responsibility of the state, and the state has created a space in which violence is allowed.

Talia Baroncelli

Could you explain the morality police a bit more? I think there is a difference between the morality police and, for example, the Revolutionary Guard. Who actually constitutes them?

Assal Rad

The Revolutionary Guard, the IRGC is part of the military apparatus of the state. There’s a traditional military, and then the IRGC has a totally different function, but those are military branches of the state. Then you have the policing of the state, which also has different– you have traffic police versus [inaudible 00:03:52], which is more broad-based, what the police do in any state. The morality police, Gasht-e-Ershad, from my experience and from what I’ve seen from other people, for the most part, they’re there to enforce the outer appearance, the dress code, and the attire. This is focused on women, even though there’s also a dress code for men. The dress code is much more strict for women. For instance, men can’t wear shorts. Clearly, neither can women. My point is to say that the dress code goes beyond just women, but it is much stricter for women, and that’s who is targeted and enforced by the morality police.

This is something that was established in the early years of the revolution when these laws were first imposed. I think everything was followed more strictly. Over time, people resisted this because they didn’t want it. The first protest against the hijab was the day after the hijab, compulsory hijab was announced. This is not new. It’s not like Iranian women suddenly woke up one day and thought, we want to have autonomy. They wanted autonomy the entire time.

Over the years, you have something like Gasht-e-Ershad, the morality police, to enforce those laws, as people themselves, in their everyday practices, start to loosen the way that they wear it as very simple acts of defiance.

Talia Baroncelli

Under the current President, Ebrahim Raisi, he’s an ultra-conservative. I think the morality police have been enforcing some of those laws much more diligently than they had been in the past. I know Iran is still a bit different from places like Saudi Arabia or Afghanistan, where women have to wear a full chador or a complete long face covering, and they can show a bit of their hair. I think there has been a bit of leniency in the past, but now it seems like they’re really cracking down on how women wear head scarves.

Assal Rad

Yeah, it depends on who– the political climate and the administration in power will impact how these laws are enforced. The law, as it’s written, is very strict. It’s just the oval of your face, your hands, that’s it. That’s all that’s supposed to be showing. That’s the way that the law is written. If there is leniency, that leniency comes– again, I emphasize this because it’s so important to understand that there’s constant resistance coming from the Iranian people. It doesn’t have to be in the form of large-scale protests. Again, there are everyday simple acts or acts of defiance. The leniency comes from the fact that you just have millions of people who aren’t doing it the way that you want to do it. Depending on who is in power, they will create an atmosphere that imposes that more or less strictly.

Of course, Ebrahim Raisi is, like you said, an ultra-conservative. It’s not just this that we’re seeing an increase in repression since his administration has come into power. Now, that doesn’t mean there was no repression before his administration. There clearly was, but we’re talking about scale and increase. A few months ago, you saw filmmakers being arrested, [inaudible 00:07:20] being arrested.

Talia Baroncelli

[inaudible 00:07:25].

Assal Rad

Yeah, across the board, there is more pressure on, and there’s more silencing of dissent, any form of dissent. That is happening. While it happened before, it’s simply happening more now. It’s more strict. There’s more imposition of the regulations. The way that Mahsa was handled, in and of itself, shows you why that climate is so important. Why who is in power, the discourse they use, and the environment they create are so important.

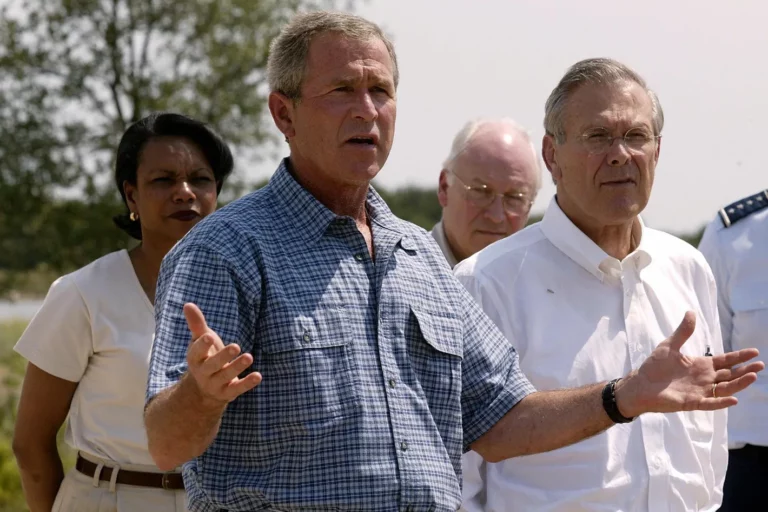

I tend to, especially for an audience that is Western, make parallels so we can understand it. If you look at the atmosphere– a lot of people said things like, “oh, when [Donald] Trump became President, all the people who were racist came out.” I said, “well, it’s not just that. It’s also that he was emboldening that discourse and using it.” You also create an atmosphere where people might feel emboldened to do and act in certain ways. You have to consider that in the Iranian case as well. While all of those things may have existed before, all the laws may have existed before, this particular administration is imposing a larger broad-based crackdown on Iranian society.

Talia Baroncelli

Also, looking at this particular administration, one of your colleagues, Trita Parsi, recently wrote in an article that “this regime is pretty much allergic to any sort of reform.” I wonder if you think that reform or whether reform can be enacted or achieved from within, or if Iranians have to try and bring about some– I don’t want to say regime change because that would assume that there would be an outside actor, but some sort of revolution or even a small change in the government. Is that possible?

Assal Rad

I think sometimes we get caught up in the semantics. A revolution would be the toppling– typically, it is described as the toppling of a system. Historically, when we look at revolutions, it was the toppling of monarchies because feudal systems were the way of governance. Then it introduces these ideas like constitutionalism and self-governance. That’s like the classic notion of revolutions that you see in things like the American Revolution and the French Revolution. Of course, that’s not the only way that you can define it– the Iranian Revolution in 1979 was a revolution at the top of the monarchy. It didn’t establish a democratic state but established the Islamic Republic, which is not only theocratic, so it’s not only non-secular. The idea of [inaudible 00:10:06] that was imposed into the constitution also made it an authoritarian state by its very nature, by its very definition, in the way that it was in the constitution.

Can it be amended? Can the Iranian constitution be amended? It has, but not necessarily for a good cause. For instance, in 1989, when there’s– only thus far, in the history of the post-revolution, there’s been one transition of power from the Supreme Leader; from [Ayatollah Ruhollah] Khomeini to [Ayatollah Ali] Khamenei. I know their names sound familiar or sound the same, but they’re different people.

Talia Baroncelli

They’re not the same person.

Assal Rad

Oftentimes people say Khomeini said this. I’m like, Khomeini has been dead for a very long time. This is a different guy. The constitution was amended because Khomeini did not have the religious credentials to be able to take that mantle. It was amended. During the Khatami administration in the early 2000s, he introduced twin bills to try and give more power to the office of the President and reduce power, say, like the Guardian Council. This concept exists within it, but whether or not the system, and by the system, I mean those who wield the most power within it, will actually allow it is a different question.

What you’re looking at in these protests is Iranians asking for fundamental change.

Talia Baroncelli

Right.

Assal Rad

Yes. First of all, even if the only thing they were asking for, which it isn’t, but even if the only thing they were asking for was the freedom of their attire and getting rid of the morality police and the dress code, by making the veil a choice, that arguably is revolutionary. That arguably is a fundamental change because it’s such an important symbol within the foundation of that state, the control of women’s bodies, just the control, the amount of control that it tries to wield over the lives of ordinary citizens. So that act in and of itself, I think you could describe in that way.

Talia Baroncelli

It would also be similar to the revolution because initially, the revolution was primarily led by women who wanted to be able to wear a hijab because they felt that they weren’t able to wear the headscarf under the Shah rule. There are some parallels there with this revolutionary act of protesting what they can and cannot wear.

Assal Rad

Yeah, I mean, the pendulum swing is important to understand in the Iranian case. It was his father in the 1930s that actually outlawed the chador and banned it. It was illegal. They actually stripped women of them at that time. The last Shah, his son, it wasn’t that it was banned because it wasn’t. It wasn’t that you couldn’t wear a hijab. It’s that because of the nature of the society and the imposition of Westernization, to a certain extent. It wasn’t that group of people; if they were more conservative, if they were more religious-minded, if they wanted to wear the scarf, they felt discriminated against. Disenfranchised versus something being– it’s not illegal to do it, but there are these differences in the way that society treats people with it. Maybe you’d have more difficulty getting a job if you were wearing it, for instance.

Talia Baroncelli

[inaudible 00:13:41] not as Western or educated in doing so.

Assal Rad

For the same reasons, those types of discrimination exist now. If the person that’s hiring you is Islamaphobic and a woman is choosing to wear a headscarf, even in the United States, that might cause discrimination against them because that’s the sort of environment we live in. It became a symbol of resistance because part of the way that Iranian revolutionaries, not all of them, but certain segments of them, understood it was as a symbol of resistance. It is seen that way in other contexts, in other historical contexts, and in other countries as well. That’s why at the core of it is choice.

You see, in these protests right now, people who are coming in support of Iranian women include Iranian women who choose to wear the chador. They’re wearing a chador. You can clearly see their own personal point of view, but they support women’s choices. It comes down to a question of choice, and that’s what they haven’t been given for the last 43 years.

Talia Baroncelli

So maybe, shifting our gaze slightly westward now, maybe we could speak about the Left in Europe as well as in North America, where you currently are. I’ve seen some voices on the Left arguing that these protests can’t possibly be organic if they’re exclusively focusing on human rights or women’s rights and that they somehow detract from the history of U.S. intervention and repression and history of Western coups in the region. So I’m wondering how we could walk and chew gum at the same time and acknowledge the fact that these protests are organic and there is a ground solid support for changing some things in Iran, and people are suffering from the sanctions and from other Western political restrictions. Maybe we could speak about that as well.

Assal Rad

Yeah, of course. I’ve been attacked by some leftists. Not everybody. There are a lot of people that I know on the Left who are very much in solidarity with the protests. I’ve also gotten attacks that by showing solidarity with the Iranian women, by posting about these protests, I am somehow supporting an imperialist takeover of Iran. That is extraordinarily frustrating for so many reasons. First of all, I’m very outspoken about my views on U.S. imperialism; that’s one issue. There are other issues.

Have sanctions devastated the Iranian economy, creating pressure on ordinary people from the middle to the working class? Yes, there’s no doubt about that. Is the intention of sanctions as a policy, very often, to foment unrest and instability in countries? Yes. Did sanctions force women to wear a hijab? No. Did sanctions create the morality police? No. Did sanctions create an atmosphere in Iran where those who wield power can use violence against their own citizens with impunity? No. Those are all the responsibilities of Iranian officials. I think there’s a problem on both sides when you try to undermine legitimate grievances, legitimate issues that affect human rights.

On the other side, on the flip side, I take issue with people on the Left who make this argument. You’re completely just undermining their agency as if these people are not out there knowingly risking their lives for– for what? They’re doing it for themselves. They’re doing it for their country and their cause. They’re doing it for their freedom and their future. That’s not solidarity. We should be able to show solidarity in every situation.

On the flip side, you have appropriated these protests for the advancement of exactly what we’re talking about, which is people saying things like, “see, sanctions were the best idea. That’s what we said. We were right.” To me, the problem with that is we use human rights language to talk about what’s going on right now. This is centered around human rights: the right of any individual for their own autonomy, for their own freedom, women’s rights, the right to expression, and the right to protest. All of this is framed in human rights language, but so is the language about sanctions. That’s the thing that’s so frustrating. If you were for human rights, you can’t selectively do that because human rights language also was used to frame why sanctions were problematic, why sanctions are when they’re broad-based and unilateral when they’re nationwide, and how it adversely impacts civilian populations. Collective punishment is against international law. There has to be some way of talking about these things with some level of consistency. I think on both sides, there have been problematic takes, and that’s why I’ve tried to emphasize listening to what Iranians are saying. The Iranians are not talking about sanctions right now. That’s not their current issue. We should very easily be able to get behind and have solidarity with people who are demanding their most basic rights. It should not be a controversial take.

Talia Baroncelli

Yeah, if the West really cared so much about human rights in Iran, then they wouldn’t have imposed sanctions during the Covid 19 pandemic, which cut off so many necessary humanitarian supplies, medicine, or other things to Iran. There is a bit of a double standard there.

Assal Rad

Well, you have a campaign– Israeli women standing with Iranian women. While that is positive, I’m sure there are women in Israel, there are Israeli women who very genuinely stand with Iranian women and who may even stand with Palestinian women. The function of a state that itself carries out human rights abuses and then uses this as a way to differentiate itself. That’s what I’m saying. There’s just so much disingenuous in the way some of the support is coming in too. Let’s just apply these things to everyone. Human rights are extremely important, but they’re not only important in Iran. They are just as important in Iran as they are everywhere else. They are equally important in every context, in every situation.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, that’s also one of the negative aspects of social media where everyone’s trying to virtue signal and put themselves out there and make themselves somehow part of whatever is going on to draw attention to themselves. So yeah, you definitely see people basically posting about what’s going on in Iran for their own personal gain or to gain media attention.

Assal Rad

You have U.S. politicians who are quite literally stripping women of their rights in the United States as we speak, tweeting about women’s rights in Iran. I’m not comparing the two situations. Women in the U.S. have a great deal more autonomy and rights than they do in Iran. I’m not paralleling that concept, but it is still– you can imagine as an American woman listening to what is happening in this country and listening to politicians who are actively seeking the policies that have just undone decades of women’s rights in the U.S. It’s not a small deal. It’s still a very big deal, especially for the lives that it’s going to impact in the U.S. It’s a women’s rights issue. It’s a global issue. It is frustrating to see this kind of– yeah, it’s like almost like double speak. I agree with you here, but then why don’t you agree when it’s our own population? It’s our own thing. So yeah, you see this across-the-board; people using this in various ways to fit there– to your point, just to get clicks or to get likes, so to speak.

Talia Baroncelli

Right, well, you’re a historian, so would you say that the current protests actually constitute a social movement, or is it really not yet at that stage? Is this something that’s continuous and can’t really be characterized in that manner?

Assal Rad

I think you could characterize it in that manner because I actually don’t think that– the initial protest might be a reaction to an event, but they are part of a very long history of protest movements, social movements, and political movements in Iran. If you look at the hijab specifically, then you can go back all the way to 1979, the first International Women’s Day and the first time women protested against it. If you’re looking at women’s rights, that goes back decades as well. The women’s rights movement in Iran is part of the reason why they finally got the right to vote in the 1960s. If you look at social and political movements in Iran, that goes back over a century. It goes back to the idea of constitutionalism at the core of it. When we say that what they are protesting is the system at its core, because the underlying thread in all of these protests and all of these movements is people, as a country and as a nation, want a government that is representative of them in the sense that it is acting their will. They believe– so the audacity for Iranians to believe that they should be independent of foreign powers, that they should have control over their resources, that their government should be a government that is governed by the people, and that there should be a constitution that creates accountability for the people who are in power. All of these things have been part of this for, like I said, over a century. I wouldn’t think of this as a spontaneous thing that’s fixated on one issue. I think you can see those threads and those roots throughout the history.

Now, defining this moment is hard to do because we’re still in it. It’s hard to define what will happen. It’s hard to know what will happen. I think it’s fair to say that this is part of that long tradition. There’s also a reason why the state reacts the way that it does. Why it acts so desperately, really, to squash, these protests is because they don’t want that fundamental change. They want to maintain the status quo. They want to maintain their own survival, and that’s not what the people want. Now more than ever, I think we’re seeing the level to which they are going to resist. It’s not going to go away. If anybody thinks this is just going to go away, they’re just going to squash the protests, and that’ll be over. Maybe in the short term, you’ll see something like that, but that doesn’t mean that a movement has died. That doesn’t mean– that’s why you have protests throughout this history and throughout this period.

I definitely think, especially now, when you hear things like teachers boycotting, students boycotting, labor, movements getting involved, just acts of civil disobedience, women going out and just not wearing their hijab. They’re not protesting. They’re not protesting. They’re just walking down the street without a hijab. That is an act of defiance. So that type of civil disobedience and these movements coalescing together create the notion of a social movement. Every movement doesn’t have to culminate in an immediate grand change to be very important. I think that’s something to emphasize too. If there isn’t a revolution tomorrow in Iran, that doesn’t mean that this was a failure.

Talia Baroncelli

I mean, every act in itself is valuable and meaningful. I was also wondering– [crosstalk 00:26:15]

Assal Rad

Just the fact that they’re changing the conversation. Not only that but on a global scale, all of those things, all of those are already victories in my view.

Talia Baroncelli

How would you compare these protests to, say, the 2009 Green Movement, which protested the results of the election, and then in 2019, we had protesting against exorbitant fuel prices? How would you characterize these protests compared to the recent ones which preceded them?

Assal Rad

Well, 2009 was quite different because it was tied to a political movement at the time; it became the Green Movement. It was tied to this idea of Iranian reformists going back to Mohammad Khatami in the ’90s and early 2000s. Not necessarily having a revolution, but wanting to reform the system in a fundamental way so that there’s more power for the Iranian people. The government actually works in their interest.

In 2009, there’s a great book about the 2009 protest, basically, everything that happened in 2009, the Green Movement called Contesting the Iranian Revolution by Pouya Alimagham, who teaches at MIT. In it, he talks about this taboo that was broken in 2009. Initially, when protesters went out in 2009, their first slogan was “Where is my vote?” That suggests this notion of accountability. They’re engaging in the political system, and therefore they think the political system should be accountable to them. As those protests evolve, you start hearing, for the first time, these chants of “death to the dictator”. It goes directly to the core of the system. In the book, one of the things he argues is that once that taboo is broken, that’s why it’s a watershed moment. Once that taboo is broken, now immediately you hear those types of chants and slogans.

Even in 2000, even right now, while one of the core slogans that we’ve heard over and over again is “women, life, freedom” which sums up exactly what everything is about, you still also see the “death of the dictator” slogans as well being used throughout the protest.

In that sense, you can see parallels. The reason why 2019 is different is in November of 2019, those protests were sparked by a hike in gas prices. There were less middle-class Iranians involved; it was more working and poor Iranians who were going to be very deeply impacted by such an extreme hike in gas prices. It was an economic issue that sparked it. In this case, you have a social issue that sparked it, and now the middle class is more involved. In 2019 you had less protests in Tehran. Now you see a lot of protests in Tehran, the capital city.

All of these protests have their own unique qualities and features. I think the other thing that’s distinct in these protests is Iranians fighting back. Not just– actually, we’ve seen these videos. They’re incredible in certain ways. You actually see crowds surrounding security forces or a police officer. That, to me, is another taboo that’s being broken. It’s important to understand it if we’re going to look at the long term of where these protests will go and how they will evolve, and what lengths people might be willing to go to in order to see that change fulfilled.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, despite Iran’s isolation, it still is part of a capitalist economic system. The middle class has continued to be hollowed out. Maybe more people are even more impoverished than they used to be prior to the pandemic. Maybe we’ll see not just what used to be the middle classes but all sorts of people protesting over the coming weeks.

Assal Rad

At that point, when you look at– there’s a lot of commentaries that say enough is enough, or they have nothing to lose. There’s this idea of having nothing to lose. Part of that does come from economic pressure as well. They’re just feeling pressure from every side. You have the sanctions reimposed in 2018, which causes hyperinflation in the country; hyperinflation, unemployment, and their currency just taking a nosedive. The entire economy has just been in a state of decline. Obviously, it affects people’s daily lives, and that’s the number one thing that people always care about, rightfully so. You care about your livelihood before you care about anything else. When you have nothing to lose, then you see the force with which protesters are coming out because they’ve gone through the pandemic, they’ve gone through sanctions, and on the inside, they’ve gone through extensive crackdowns and protests being met with deadly force, more restrictions, more crackdowns across Iranian civil society. You can understand where this level of frustration comes from and why it’s targeted across the board.

Talia Baroncelli

People seem to be increasingly frustrated, and the economic situation isn’t helping. I wonder if, given these protests, if the U.S. will be more likely or less likely now to rejoin the JCPOA, the Iran nuclear deal.

Assal Rad

Well, this is what the Biden administration has said or what we’ve heard so far. The deal will not, in any way, impede the administration’s ability or will to condemn and hold Iran accountable for human rights abuses. I would love it if the administration or the U.S. government, in general, would hold everybody accountable for human rights abuses, but I guess that’s wishful thinking on my part.

In the case of Iran, this is what’s been said. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said, “we’ve sanctioned the morality police. We’ve sanctioned specific actors. They will continue– they’ve worked on–” and our organization actually pushed for this, and has been pushing for this for years, by the way– an update to the general license to GLD1, so that our sanctions aren’t impeding access to the internet for Iranians. On the Iranian side, authorities are shutting down the internet. Another action that we can take as the U.S. in support of protesters is to make sure that we are not inadvertently aiding their ability to block them from the internet. Some things are blocked, access is blocked from the U.S. side, from U.S. tech companies. This is what the Biden admin is saying.

At the same time, they’re saying, “look at the height of the Cold War, when the Soviet Union was the evil empire and the greatest enemy of the United States, we still negotiated arms agreements.” Which makes sense. It makes sense to do so because if you look at how nuclear weapons affect the way that we calculate political decisions, you understand why it’s so important that an authoritarian state that is already subduing its people in this manner would be even more dangerous if it made the political decision to acquire a nuclear weapon. It’s not just a matter of– and I say that the political decision because thus far, Iran is still a signatory to the NPT even if the administration still says they’re open to returning to restoring the JCPOA under whatever circumstances they’ve come up with. If that authoritative state then has a nuclear weapon, it’s more dangerous not only for its own people but for the consequences, the arms race that it can set off. [crosstalk 00:34:54]. Sorry, what?

Talia Baroncelli

The regional arms race as well with Saudi Arabia.

Assal Rad

Exactly. So that’s the line we’ve heard so far from the Biden administration, which is, even if we are continuing negotiations, that doesn’t change the human rights issue. We’re still going to go after actors and hold accountable people who are human rights abusers. On the flip side, even with the worst of the worst– this is their lines. “Even with the worst of the worst, we maintain arms agreements.” That’s how the JCPOA is being understood, at least from our understanding of how they’re looking at it.

Talia Baroncelli

So basically, there are still lines of communication that are open and diplomatic lines of communication, but they’re maybe not as direct as under the Obama administration when there was actually–

Assal Rad

Well, they haven’t been. They haven’t been. Even before the protests, because the Biden administration never returned to the deal. A lot of the way that it’s talked about, sometimes officials from the Biden admin will say things like, “oh, Iran has to return to the deal.” Well, Iran is in the deal. The only country that’s outside of the deal is the U.S. Whereas, in 2014 and 2015, you had pictures of Javad Zarif and John Kerry while they were talking to each other. While you had direct negotiations then, because the U.S. is not a party to the deal, they are not part of the direct negotiations. It’s been indirect the entire time. I think the negotiations have now been going on for something like 16 months, but basically, since April of 2021, that’s when the first round of negotiations started. They haven’t been direct, and obviously, diplomacy works much better if you can actually have direct conversations. That hasn’t happened yet.

Talia Baroncelli

Right. Well, I mean, it was the cornerstone of Biden’s presidential campaign to get the U.S. to rejoin the JCPOA. Do you think that he said those things in bad faith or that he maybe changed his mind along the way, potentially to cozy up with Saudi Arabia and to increase oil production? What do you think happened there?

Assal Rad

It’s hard to say what this individual person’s thinking was; I obviously don’t know that. There is, I mean, looking at it, at least from the outside, president Biden, when he was a candidate and even before he was a candidate– I mean, the first time we hear Biden talking about Trump’s Iran policies is back in 2017, before the U.S. even leaves the deal. Trump was so outspoken about the fact that he hated the deal and he wanted to leave the deal. Joe Biden was warning in 2017 that this is a terrible decision; we shouldn’t do it. In 2018 when the U.S. withdrew, he strongly criticized the Trump administration. He did so on many things, but specifically on the Iran deal front, Secretary of State [Antony] Blinken before he was Secretary of State. All of the Biden officials were extremely critical of this decision by the U.S. under the Trump admin. It would have theoretically made sense, and people who were proponents of diplomacy and supported Biden’s campaign urged the Biden administration to take action earlier in his admin because Iran was going to have an election in June of 2021. This was always the fear. The fear was, well, now, right now, you have a moderate, engagement-friendly administration in Iran. This was their core accomplishment, which was the JCPOA in 2015. They were much more likely to return to compliance if the U.S. returned to the deal in a manner that was more efficient than what we’ve seen. It’s precisely what happened with the Raisi administration, which, while it has said that it wants to return to compliance, if all parties return to compliance and there are certain guarantees, that’s really the end of diplomacy between the West and this admin. They’ve made it a point to say that they’re not looking at the West. They’re trying to engage with their neighbors in the region, with China, and with Russia. It’s a pivot away from the United States, is what you’re seeing with this admin.

I think that part of what you have to consider for any U.S. politician; first of all, Joe Biden had a lot of stuff to deal with. We were still healing from the pandemic. There are a lot of domestic issues in the U.S. that I know people want to ignore, but there are a lot of concerns in terms of divisiveness and what’s happening in the U.S. itself. There’s that, but also there’s this overriding anti-Iran attitude that exists within the political discourse, within popular culture, within the media, in the U.S. that paints the way we see policies, and it sometimes explains why our policies don’t make sense. They actually don’t make sense for us. It doesn’t make sense in terms of U.S. national security interests, global security interests, to have quit and left the deal or to have taken this long to simply return to the deal. Because there is so much anti-Iran attitude that exists within our politics, that’s what they mean by a political cost. It’s very interesting. It would be a political cost if Biden were to return to the deal. This, despite the fact that a bipartisan majority of Americans support a deal– bipartisan, means Trump supporters and Biden supporters. It’s interesting if you think, then what does political cost mean? That means political cost in DC. That doesn’t mean the U.S. populist. The U.S. populist supports it because they do not want a war with Iran. The U.S. populist supports it. The rhetoric of DC will have a political cost, especially when you consider how Israel, which is a key U.S. ally and wields a fair amount of influence, is against the deal as well.

There are a lot of things, I guess, you could think about in terms of explaining it, but it is frustrating for people who supported his administration and thought that he would actually return to the deal very early on, which he didn’t do.

Talia Baroncelli

I’ve heard you say in the past; I think this is one of our previous conversations, that the American elite, especially the GOP, is perhaps more dogmatic than the Iranian establishment when it comes to these issues.

Assal Rad

We talk about hardliners. We call them hardliners in Iran. We call them hawks in the U.S. They’re basically the same thing. These are the people who never wanted a deal to begin with because they’re more comfortable in this adversarial status quo. In neither situation does that reflect the will of the populace, at least at the time. At the time the deal was reached, we saw scenes of Iranians celebrating in the streets. Seventy percent of Iranians turned out in the 2017 election to re-elect the Rouhani administration.

I always say this, I’m like Ebrahim Raisi wins in 2021 with extremely low voter turnout for Iran. In 2017, 70% of voters turned out. In 2021, I think it’s something like 48% and maybe even less because a lot of the votes were just blank votes. That’s the choice. It’s a boycott of the vote, almost. Raisi is the one who ran against Rohani in 2017 and lost by millions of votes. The political climate in Iran has also changed over these years, in part as a consequence of policies that didn’t work, things that didn’t work out in any way, and nothing helped them. Their situation has gotten continuously worse.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, in the case of Raisi, do you think that people specifically didn’t go out to vote because they felt completely disillusioned and they didn’t think that he would actually want to work with the West and that the West wouldn’t rejoin the deal with Raisi at the helm? Or do you think there’s something else that explains that?

Assal Rad

I think people didn’t turn out to vote for a combination of reasons. Feeling disaffected just in general with a system that doesn’t work, that doesn’t help them, that doesn’t serve them. The fact that the election process in Iran, it’s not like it’s totally democratic. The candidates are always vetted by an unelected body, and so it is undemocratic from the very beginning. There are democratic elements to it, we should say. In 2021, there was like ultra vetting. No one was allowed to run. So it was almost as if they were appointing Raisi as President rather than actually having anything that would resemble a real election. So that’s part of it too. I mean, it was the fact that they weren’t really given choices. It was the fact that they were disappointed with the political system altogether. You can understand, after everything that they’ve been through with COVID, with sanctions, with protests being repressed, that they really didn’t have a desire to go out and vote. I always say that that’s a political decision too. They don’t just have agency when they do vote. They also have agency when they don’t vote.

Talia Baroncelli

Right. That in itself is a political act as well.

Assal Rad

There are millions of blank ballots, so that’s an effort to show that you’re not voting. I’m not just going to sit here. I’m going to take action to show you that I’m not voting.

Talia Baroncelli

Okay, Assal, thank you so much for joining us. I think we’re running out of time now, but it would be really great to have you on again to speak about your book State of Resistance. Next time, maybe we can go into more detail.

Assal Rad

I would love to.

Talia Baroncelli

We can look at post-revolutionary Iranian national identity and also what led up to the 1979 revolution. Assal Rad, a historian and research director at the National Iranian American Council. Thank you very much for joining us.

Assal Rad

Thank you for having me.

Talia Baroncelli

See you next time. Bye.

Talia Baroncelli:

Hola, soy su anfitriona invitada Talia Baroncelli en Berlín, y está viendo theAnalysis.news. En breve me acompañará Assal Rad para hablar sobre las protestas en Irán. Por favor, no olvide donar visitando el sitio web theAnalysis.news y también registrar su correo para recibir todos los enlaces a los próximos programas. Volvemos en unos segundos.

Me acompaña ahora Assal Rad. Es historiadora y directora de investigación del Consejo Nacional Iraní-Estadounidense y autora de un libro reciente titulado The State of Resistance: Politics, Culture, and Identity in Modern Iran. Muchas gracias por acompañarnos, Assal.

Assal Rad:

Gracias por invitarme.

Talia Baroncelli:

El 13 de septiembre, Mahsa Amini murió en el hospital tras recibir una paliza a manos de la policía moral, o al menos presuntamente estando bajo su custodia. Y desde entonces hemos visto protestas en todo Irán. Hemos visto protestas no solo en los centros urbanos, sino también en las zonas rurales. Y quería hablarte sobre el resentimiento por parte del pueblo iraní hacia el régimen,así como algunos de los factores socioeconómicos que han impulsado la protesta hasta ahora.

Assal Rad:

Sí, por supuesto. Lo primero a lo que nos referimos cuando hablamos de qué pasó específicamente con Mahsa Amini, porque creo que hay muchas capas de historias que están sucediendo en este momento y, por supuesto, fue provocado por este horrible hecho, por el asesinato de Mahsa Amini. Y la única cosa que sigo queriendo recalcar, porque creo que a veces hay gente, y lo entiendo, que no diría que fue golpeada por la policía moral… la llamada policía moral, en la parte trasera de la furgoneta. Los medios de comunicación iraníes intentan publicar videos que dicen: “Miren, ella iba caminando”. El resultado final, independientemente de lo que diga la gente, es que ella nunca debería haber sido detenida. Ella nunca debería haber estado en una situación en la que la colocación del pañuelo de la cabeza sería un motivo para detener a esta joven. Y claro, si no hubiera sido detenida, si no hubiera sido acosada por la policía moral, hoy estaría viva. Así que esto es claramente responsabilidad no solo de las personas que la detuvieron, sino de un Estado que permite este tipo de leyes draconianas, que impone estas leyes a su pueblo, pero también que permite la violencia contra sus civiles con impunidad. Un sistema en el no hay rendición de cuentas de sus funcionarios cuando usan violencia contra su propio pueblo. Y lo que estamos viendo en las protestas es indicativo de eso. Así que solo quería plantear eso desde el principio. Que las narrativas cruzadas no importan. No debería haber estado allí. Es responsabilidad del Estado, y el Estado ha creado un espacio en el que se permite la violencia.

Talia Baroncelli:

¿Podrías explicar un poco más qué es la policía moral? Porque creo que obviamente hay una diferencia entre la policía moral y, por ejemplo, la Guardia Revolucionaria. ¿Y quién los constituye realmente?

Assal Rad:

La Guardia Revolucionaria, la IRGC, es parte del aparato militar del Estado. Hay una especie de militares tradicionales y luego la IRGC tiene una función totalmente diferente, pero esas son ramas militares del Estado. Luego tienes la vigilancia del Estado, que también tiene diferentes… policías de tránsito, a diferencia de que tiene una base más amplia, lo que hace la policía en cualquier Estado. Pero la policía moral, Gashte Ershad, según mi experiencia y por lo que he visto de otras personas, quiero decir, en su mayor parte, están ahí para hacer cumplir la apariencia exterior, el código de vestimenta en el atuendo. Está enfocado a las mujeres, aunque también existe para los hombres. El código de vestimenta es obviamente mucho más estricto para las mujeres. Por ejemplo, los hombres no pueden usar pantalones cortos. Las mujeres tampoco. Quiero decir que el código de vestimenta va más allá de las mujeres, pero es mucho más estricto para las mujeres, y son el objetivo de la policía moral a la hora de hacer cumplir el código.

Así que esto es algo que se estableció especialmente en los primeros años de la revolución, cuando estas leyes fueron impuestas por primera vez. Creo que todo se siguió más estrictamente. Pero luego, las personas se resistieron porque no lo querían. Las primeras protestas contra el hiyab fueron al día siguiente de que se anunció el hiyab obligatorio. Así que esto no es nuevo. Las iraníes no despertaron de repente y pensaron: “Queremos tener autonomía”. Querían la autonomía todo el tiempo.

Así que a lo largo de los años, aparece el Gashte Ershad, la policía moral, para hacer cumplir esas leyes, conforme las personas, solo en sus prácticas diarias, lo usan de manera menos estricta. Como simples actos de desafío.

Talia Baroncelli:

Y también bajo el actual presidente, Ebrahim Raisi. Es un ultraconservador. Creo que la policía moral ha aplicado algunas de esas leyes mucho más diligentemente que en el pasado, porque sé que Irán todavía es un poco diferente de lugares como Arabia Saudita o Afganistán, donde las mujeres tienen que usar un chador completo una especie de velo facial largo, y pueden mostrar un poco de su cabello. Así que creo que hubo algo de indulgencia en el pasado, pero ahora parece que realmente están tomando medidas enérgicas contra la forma en que las mujeres usan el pañuelo.

Assal Rad:

Sí. Depende de… El clima político y la administración afectarán cómo se hacen cumplir estas leyes. Porque la ley tal como está escrita es muy estricta. Es solo el óvalo de tu cara, tus manos. Es todo lo que puedes mostrar. Así está escrita la ley. Pero si hay indulgencia, tiene lugar… Nuevamente, enfatizo esto porque es muy importante entender que hay constante resistencia proveniente del pueblo iraní. No tiene que ser siempre en forma de protestas a gran escala. Como digo, son actos cotidianos o actos de desafío. Entonces, la indulgencia proviene del hecho de que hay millones de personas que no lo están haciendo como tú quieres. Y dependiendo de quién esté en el poder, crearán una atmósfera que imponga eso más o menos estrictamente.

Y por supuesto, Ebrahim Raisi es, como dijiste, ultraconservador. Y no es eso lo que estamos viendo en términos de aumento de la represión desde su llegada al poder. Había represión antes de su administración. Claramente la hubo, pero estamos hablando de escala y aumento. Y entonces, hace solo unos meses, vimos que arrestaban a cineastas, Jafar Panahi. Sí. Quiero decir, en todos los ámbitos hay más presión y hay más silenciamiento de la disidencia, cualquier forma de disidencia. Y aunque sucedía antes, simplemente está sucediendo más ahora. Es más estricto, hay más imposición de las normas. Y la forma en que trataron a Mahsa en sí misma muestra por qué el clima es tan importante, por qué quien está en el poder, el discurso que usan, el entorno que crean, es tan importante. Y tiendo a señalar paralelismos, especialmente para una audiencia occidental, para que podamos entenderlo. Si miras la atmósfera, mucha gente dijo cosas como: “Con Trump, salieron todos los racistas”. Y yo dije: “Bueno, no es solo eso. también es que… al permitir ese discurso y usarlo, también creas una atmósfera donde la gente se atreva a actuar de cierta manera”. Y también hay que considerar eso en el caso iraní. Si bien todas esas leyes pueden haber existido antes, esta administración en particular está imponiendo una represión más amplia contra la sociedad iraní.

Tara Baroncelli:

Sí. Y también considerando esta administración en particular, uno de tus colegas, Trita Parsi, escribió recientemente en un artículo que este régimen es bastante alérgico a cualquier tipo de reforma. Así que me pregunto si crees que la reforma se puede ejecutar o lograr desde adentro, o si los iraníes simplemente tienen que tratar de lograr algún tipo de… no quiero decir cambio de régimen, porque eso supondría que sería un actor externo, sino algún tipo de revolución o incluso un pequeño cambio en el Gobierno. ¿Es eso posible?

Assal Rad:

Creo que a veces es una cuestión de semántica. La revolución sería el derrocamiento… Se describe como el derrocamiento de un sistema. Históricamente, cuando analizamos las revoluciones, era el derrocamiento de las monarquías, porque los sistemas feudales eran la forma de gobierno. Y luego introdujo estas ideas como el autogobierno, constitucionalismo, que es la idea clásica de revoluciones que vemos, por ejemplo, en la revolución estadounidense y la revolución francesa. Por supuesto, no es la única forma de definirlo. La revolución iraní de 1979 fue para derrocar al monarca. Pero no estableció un Estado democrático, estableció una república islámica. Que no es solo teocrática, no es solo no secular. La idea que se impuso en la Constitución también lo hizo un Estado autoritario por su propia naturaleza, como estaba en la Constitución.

Entonces, ¿se puede modificar? ¿Se puede enmendar la Constitución iraní? Se ha hecho, pero no necesariamente para bien. Por ejemplo, en 1989, cuando solo había habido en la historia, en la posrevolución, una sola transición de poder del líder supremo, de Khomeini a Khamenei. Sé que sus nombres suenan igual, pero son diferentes.

Tara Baroncelli:

No son la misma persona.

Assal Rad:

Porque a menudo la gente usa Khomeini, “Khomeini dijo esto…”. Khomeini murió hace mucho tiempo, este es otro. Pero la Constitución fue enmendada porque Khamenei no tiene… especialmente las credenciales religiosas para poder tomar esa responsabilidad Así que fue enmendada, durante la administración de Hatami, a principios de la década de 20, presentó dos proyectos de ley para tratar de dar más poder a la oficina del presidente y reducir el poder del Consejo de Guardianes. Así que existe este concepto integrado, pero si el sistema, y por sistema me refiero a aquellos que manejan el mayor poder dentro de él, realmente lo permitirá, es una cuestión diferente. Entonces, lo que vemos en estas protestas son los iraníes que piden un cambio fundamental.

Sí. En primer lugar, incluse si lo único que pidiesen, que no lo es, pero aunque lo único que pidiesen fuese la libertad de su vestimenta, deshacerse de la policía moral y el código de vestimenta, como elegir si llevar velo, que podría decirse que es revolucionario, podría decirse que es un cambio fundamental porque es un símbolo importante dentro de la base de ese Estado, el control de los cuerpos de las mujeres, la cantidad de control que trata de ejercer sobre la vida de los ciudadanos. Entonces, ese acto en sí mismo creo que podría describirse de esa manera.

Tara Baroncelli:

También sería similar a la revolución porque inicialmente la revolución fue dirigida principalmente por mujeres que querían poder usar el hiyab porque sentían que no podían usar el pañuelo durante el régimen del sah. Así que hay un paralelismo con este acto revolucionario de protestar por lo que pueden y no pueden ponerse.

Assal Rad:

Es importante entender el movimiento del péndulo. En el caso iraní, fue su padre en la década de 1930 quien proscribió el chador, quien lo prohibió. Así es. Era ilegal. Se los quitaron a las mujeres en ese momento. Pero el último sah, su hijo, no es que estuviera prohibido, no es que no pudieras llevar el hiyab. Es que por la naturaleza de la sociedad y el… Cómo puedo decirlo. La imposición de la occidentalización hasta cierto punto. No era ese grupo de personas, si eran más conservadores, con una mentalidad más religiosa, si querían llevar el pañuelo, se sentían discriminadas. Marginadas, en contraposición a algo que no es ilegal hacerlo. Pero existen estas diferencias en la forma en que la sociedad trata a las personas que la conforman. Quizá sería más difícil conseguir un trabajo si lo llevaras puesto, por ejemplo.

Talia Baroncelli:

No eras… tan occidental o capacitada si lo hacías.

Assal Rad:

Por las mismas razones, esos tipos de discriminación podrían existir. Si la persona que te contrata es homofóbica y una mujer elige usar un pañuelo en la cabeza, incluso en los Estados Unidos, podría ser discriminada porque ese es el tipo de entorno en el que vivimos. Así, se convirtió en un símbolo de resistencia, porque parte de la forma en que los revolucionarios iraníes, no todos ellos, pero ciertos segmentos, entendieron que era un símbolo de resistencia. Y así se ve en otros contextos, en otros contextos históricos, en otros países también. Por ello el elemento central es la elección. En estas protestas, vemos que muchas personas que apoyan a las mujeres iraníes incluyen mujeres iraníes que eligen ponerse el chador. Llevan puesto un chador. Se puede ver claramente su propio punto de vista personal. Pero apoyan el derecho a elección de las mujeres. Porque todo se reduce a una cuestión de elección. Y eso es lo quev no se les ha dado en los últimos 43 años.

Talia Baroncelli

Sí. Quisiera mirar hacia Occidente ahora. Y tal vez podríamos hablar de la izquierda en Europa, así como en América del Norte, donde te encuentras actualmente, porque he visto que algunas voces de la izquierda argumentan que estas protestas no pueden ser orgánicas si se centran exclusivamente en los derechos humanos o de las mujeres y que de alguna manera restan valor a la intervención y represión de EE. UU., la historia de los golpes de Estado occidentales en la región. Así que me pregunto cómo podríamos caminar y masticar chicle al mismo tiempo y reconocer el hecho de que estas protestas son orgánicas y hay una base de apoyo para cambiar algunas cosas en Irán y que la gente está sufriendo por las sanciones y por otras restricciones políticas occidentales. Así que tal vez podríamos hablar de eso también.

Assal Rad

Sí, por supuesto que he sido atacada por algunos izquierdistas, no por todos. Conozco mucha gente de izquierda que son muy solidarios con las protestas. Pero también he sido acusada de que por mostrar solidaridad con las mujeres iraníes, publicando sobre estas protestas, que de alguna manera estoy apoyando una toma imperialista de Irán. Y eso es extraordinariamente frustrante por muchas razones. En primer lugar, porque soy muy franca sobre mis puntos de vista sobre el imperialismo de EE. UU. Ese es un problema. Pero hay otros problemas.

Y así… Las sanciones devastaron la economía iraní, creando presión sobre la gente común, desde la clase media hasta la clase trabajadora. Sí, de eso no hay duda. ¿Es la intención de la política de sanciones fomentar el malestar y la inestabilidad en los países? Sí. ¿Las sanciones obligan a las mujeres a llevar el hiyab? No. ¿Las sanciones crean la policía moral? No. ¿Crearon las sanciones una atmósfera en Irán en la que aquellos que detentan el poder pueden usar la violencia contra sus propios ciudadanos con impunidad? No. Todo eso es responsabilidad de los dirigentes iraníes. Entonces, creo que hay un problema en ambos lados cuando intentas minimizar las razones legítimas para protestar, cuestiones legítimas que afectan los derechos humanos.

En el extremo opuesto, no estoy de acuerdo con el argumento de la izquierda que niega completamente su agencia, como si estas personas no estuvieran arriesgando sus vidas conscientemente por lo que están haciendo. Lo están haciendo por su país y su causa. Lo hacen por su libertad y su futuro. Así que eso no es solidaridad. Deberíamos ser capaces de mostrar solidaridad en cada situación.

Y luego, por otro lado, es una apropiación de estas protestas para el avance de, como estamos hablando, que la gente decía que las sanciones marítimas son la mejor idea. Es lo que dijimos. Teníamos razón. Y para mí, ¿cuál es el problema con eso? Usamos lenguaje de derechos humanos para hablar de lo que está pasando en este momento. Esto se centra en los derechos humanos. El derecho de todo individuo a su propia autonomía, a su propia libertad, derechos de la mujer, derecho a la expresión, derecho a la protesta. Todo esto está enmarcado en el lenguaje de los derechos humanos. Pero también lo es el lenguaje sobre las sanciones. Y eso es lo que es tan frustrante, que si estás a favor de los derechos humanos, no puedes hacer eso selectivamente porque el lenguaje de los derechos humanos también se usó para enmarcar por qué las sanciones eran problemáticas, cuando son amplias y unilaterales, cuando son a nivel nacional, cómo afecta negativamente a las poblaciones civiles. El castigo colectivo es contrario al derecho internacional. Tiene que haber alguna forma de hablar de estas cosas con cierto nivel de coherencia. Y creo que en ambos lados ha habido posiciones problemáticas. Es lo que he tratado de enfatizar. Solo escucha lo que dicen los iraníes. Los iraníes no están hablando de sanciones en este momento, así que ese no es su problema actual. Pero deberíamos ser capaces de apoyar eso fácilmente y solidarizarnos con las personas que están exigiendo sus derechos más básicos. Entonces, no debería ser una posición controvertida.

Talia Baroncelli:

Si a Occidente realmente le importan tanto los derechos humanos en Irán, no debería haber impuesto sanciones durante la pandemia de COVID-19, que imposibilitó el acceso a suministros humanitarios o medicamentos u otras cosas en Irán. Así que hay un poco de doble rasero aquí.

Assal Rad:

Bueno, vemos una campaña, mujeres israelíes que apoyan a las iraníes es algo positivo, estoy segura de que hay mujeres en Israel que genuinamente apoyan a las mujeres iraníes y que quizá incluso apoyan a las palestinas. La es la función de un Estado que comete abusos a los derechos humanos, y luego usa esto como una forma de diferenciarse. Eso es lo que estoy diciendo. Y también están siendo engañosos en la forma en que llega parte del apoyo. Deberíamos aplicar estas cosas a todos. Los derechos humanos son esenciales, pero no solo en Irán, son tan importantes en Irán como en cualquier otro lugar. Son igualmente importantes en todos los contextos, en todas las situaciones.

Talia Baroncelli:

Es probablemente uno de los aspectos negativos de las redes sociales, donde básicamente todos se dedican al postureo y buscan estar en primer plano y formar parte de cualquier cosa que esté pasando para llamar la atención. Definitivamente ves gente que publica en las redes sobre lo que está pasando en Irán para su propio beneficio personal o para llamar la atención de los medios.

Assal Rad:

Políticos estadounidenses que están despojando a las mujeres de sus derechos en los Estados Unidos tuitean sobre los derechos de las mujeres en Irán. Y no estoy comparándolo. Las mujeres en los Estados Unidos tienen mucha más autonomía y derechos que en Irán. No estoy haciendo un paralelo con ese concepto, pero puedes imaginar, como mujer estadounidense, escuchar lo que está pasando en este país y escuchar a los políticos que en realidad están buscando activamente estas políticas. Acabamos de deshacer décadas de los derechos de las mujeres en los Estados Unidos. Sigue siendo un problema muy grande, especialmente para las vidas que se verán afectadas en los Estados Unidos. Es un problema de derechos de las mujeres, es un problema global. Así que es frustrante ver este… Es casi un doble discurso, “Estoy de acuerdo contigo aquí”. ¿Por qué no estás de acuerdo cuando se trata de nuestra propia población? Así que sí, ves esto en todos los ámbitos. Usan esto de varias maneras para que se ajuste a su argumento, solo para obtener clics u obtener me gusta, por así decirlo.

Talia Baroncelli:

Bien, bueno, eres historiadora, entonces, ¿dirías que las protestas actuales en realidad constituyen un movimiento social o aún no está en esa etapa o es algo continuo y eso realmente no se puede caracterizar de esa manera?

Assal Rad:

Creo que se puede caracterizar de esa manera porque en realidad no creo que las protestas iniciales puedan ser una reacción a un acontecimiento, sino que son parte de una historia muy larga de movimientos de protesta, movimientos sociales, movimientos políticos en Irán. Si consideras específicamente el hiyab, puedes retroceder hasta 1979, el primer Día Internacional de la Mujer, la primera vez que las mujeres protestaron contra él. Si consideras los derechos de las mujeres, también se remonta varias décadas.El movimiento por los derechos de la mujer en Irán es parte de la razón por la que finalmente obtuvieron el derecho al voto en la década de 1960. Si nos fijamos en los movimientos sociales y políticos en Irán, se remontan a hace más de un siglo. A la idea de constitucionalismo en el centro de la misma. Cuando decimos que protestan por el sistema en su esencia, porque el hilo subyacente en todas estas protestas y todos estos movimientos es un pueblo, un país, es una nación que quiere un Gobierno que es representativo de ellos en el sentido de que en realidad actúa según la voluntad de ellos como creen. Así que la audacia de los iraníes en querer ser independientes de las potencias extranjeras, que deben tener control sobre sus recursos, que su Gobierno debe ser gobernado por el pueblo, que debe haber una Constitución que garantice la rendición de cuentas de los gobernantes. Todas estas cosas han sido parte de esto durante, como dije, más de un siglo. No pensaría en esto como algo espontáneo que se reduce a un solo tema. Y creo que puedes ver esos hilos y esas raíces a lo largo de la historia.

Ahora bien, definir este momento es difícil porque todavía estamos en él. Sí. Es difícil definir lo que sucederá. Es difícil saber qué pasará. Pero creo que es justo decir que esto es parte de esa larga tradición. Y también hay una razón por la cual el Estado reacciona de la forma en que lo hace. Por qué actúa tan desesperadamente para aplastar estas protestas. Es porque no quieren ese cambio fundamental. Quieren mantener el statu quo. Quieren asegurar su propia supervivencia. Y eso no es lo que quiere la gente. Y ahora más que nunca, sin embargo, creo que también estamos viendo el nivel al que van a resistir. No va a desaparecer. Si alguien cree que simplemente va a desaparecer, con solo aplastar las protestas, quizá a corto plazo sí, pero eso no significa que un movimiento haya muerto. Es por eso que vemos protestas a lo largo de todo este periodo.

Así que definitivamente pienso, especialmente ahora que vemos profesores y estudiantes que hacen boicot, movimientos laboristas que participan, actos de desobediencia civil, mujeres que salen sin el hiyab, no están protestando. No están protestando. Solo salen a la calle sin hiyab. Pero eso es un acto de desafío. Ese tipo de desobediencia civil y la unión de estos movimientos crea la noción de un movimiento social. Y no todo movimiento tiene que culminar en un gran cambio inmediato para ser muy importante. Esto es importante, si no hay una revolución mañana in Irán, eso no quiere decir que esto fue un fracaso.

Talia Baroncelli:

Que se derrumbe. Quiero decir, cada acto en sí mismo es valioso y significativo. También me preguntaba…

Assal Rad:

Solo cambiar la conversación, y no solo eso, sino a escala global, todas esas cosas ya son victorias en mi opinión.

Talia Baroncelli:

¿Y cómo compararías estas protestas a, por ejemplo, el Movimiento Verde de 29, que protestó por los resultados de las elecciones y luego en 2019 tuvimos protestas por los precios exorbitantes del combustible? ¿Cómo caracterizarías estas protestas en comparación con las recientes que las precedieron?

Assal Rad:

Bueno, 29 fue bastante diferente porque estaba vinculado a un movimiento político en ese momento. Se convirtió en el Movimiento Verde. Estaba ligado a esta idea de reformista iraní que se remonta a Muhammad Khatami a principios de la década de 20. Quiero decir, no necesariamente tener una revolución, sino querer reformar el sistema de manera fundamental para que haya más poder para el pueblo iraní. El Gobierno realmente trabaja en pos de su interés.

En 29… Hay un gran libro sobre la protesta de 29, básicamente todo lo que sucedió en 29, el Movimiento Verde, llamado Contesting the Iranian Revolution, de Pouya Alimagham, profesor en el MIT. En él habla de ese tabú que se rompió en 29. Cuando inicialmente los manifestantes salen en 29, su primer eslogan es: ¿Dónde está mi voto? Y eso es indicativo de esta noción de rendición de cuentas. Están participando en el sistema político y que el sistema político debe rendir cuentas. Pero a medida que evolucionan esas protestas, empiezas a escuchar por primera vez los gritos de “muerte al dictador”. Va directamente al núcleo del sistema. Y en el libro, una de las cosas que argumenta es que una vez que se rompe ese tabú… Por eso es un momento decisivo. Cuando se rompe ese tabú, inmediatamente se escuchan ese tipo de cánticos y consignas.

E incluso en el… Incluso ahora mismo, mientras que uno de los lemas principales que hemos escuchado una y otra vez es de nuevo “mujeres, vida, libertad”, que resume exactamente de qué se trata, todavía ves las consignas de “muerte al dictador”, como durante toda la protesta.

Así que en ese sentido puedes ver paralelismos. La razón por la que 2019 es diferente es que en noviembre de 2019 esas protestas fueron provocadas por un alza en los precios de la gasolina. Fueron menos iraníes de clase media, eran más trabajadores e iraníes pobres, quienes obviamente iban a verse profundamente afectados por un aumento tan extremo en los precios de la gasolina. Fue un tema económico lo que lo desató. En este caso es un problema social lo que lo desencadenó, y ahora es la clase media. En 2019 vimos menos protestas en Teherán. Ahora ves muchas protestas en Teherán, la capital.

Entonces, todas estas protestas tienen sus propias cualidades y características únicas. Pero lo que distingue a estas protestas es en realidad que los iraníes están resistiendo. No solo… Y hemos visto estos videos. Son increíbles en ciertos aspectos. Ves multitudes alrededor de las fuerzas de seguridad o un agente de policía. Y eso para mí es otro tabú que se está rompiendo. Y es importante entender, si vamos a ver el largo plazo de estas protestas y cómo evolucionarán y hasta dónde estaría la gente dispuesta a llegar para implementar ese cambio.

Talia Baroncelli:

Bueno, a pesar del aislamiento de Irán, todavía es parte de un sistema económico capitalista. Entonces, la clase media aún es menoscabada y, por lo tanto, quizá haya más personas que son más pobres de lo que eran antes de la pandemia. Y tal vez veamos no solo lo que antes eran las clases medias, sino todo tipo de gente protestando durante las próximas semanas.

Assal Rad:

En ese momento, vemos muchos comentarios de gente que dice basta, no tienen nada que perder. Existe esta idea de tener algo que perder. Y parte de eso también proviene de la presión económica. Así que solo sienten presión por todos lados. Tenemos las sanciones reimpuestas en 2018, que provocan hiperinflación en el país, desempleo, su moneda cae en picado. Toda la economía viene de un estado de declive. Obviamente afecta la vida diaria de las personas. Es la principal preocupación de la gente, con razón. Te preocupas por sobrevivir antes que por cualquier otra cosa. Pero cuando no tienes nada que perder, entonces ves la fuerza con la que están saliendo los manifestantes porque han pasado la pandemia, han pasado por sanciones, y en el interior han pasado por represiones extensivas, protestas que se sofocan con fuerza letal, más restricciones, más represión en la sociedad civil iraní. Entonces, pueden entender de dónde proviene este nivel de frustración y por qué se ve en todos los ámbitos.

Talia Baroncelli:

La gente parece estar cada vez más frustrada y la situación económica no ayuda. Y me pregunto si, ante estas protestas, hay más posibilidad o menos de que Estados Unidos se reincorpore al JCPOA, el acuerdo nuclear con Irán.

Assal Rad:

Bueno, esto es lo que ha dicho la administración de Biden, o lo que hemos oído hasta ahora. El acuerdo no impedirá en modo alguno la capacidad o voluntad de la administración de condenar y responsabilizar a Irán por los abusos contra los derechos humanos. Me encantaría que EE. UU. exigiera responsabilidades por los abusos a los derechos humanos, pero supongo que eso es una ilusión por mi parte.

Pero en el caso de Irán, esto es lo que se ha dicho. El asesor de seguridad nacional Jake Sullivan, dijo: “Hemos sancionado a la policía moral, hemos sancionado a actores específicos”. Han trabajado… Y nuestra organización realmente exigió esto. Yo lo hice durante años, por cierto.

Una actualización de la licencia general… al GLD-1, para que nuestras sanciones no impidan que los iraníes tengan acceso a internet. Del lado iraní, las autoridades están bloqueando internet. Así que otra acción que podemos tomar en Estados Unidos es asegurar que no estamos ayudando inadvertidamente a que puedan bloquear la internet en lo que concierne a empresas tecnológicas de EE. UU. Entonces, esto es lo que dice la administración de Biden.

Pero al mismo tiempo dicen que durante la Guerra Fría, cuando la Unión Soviética era el imperio del mal y el mayor enemigo de los Estados Unidos, aun así negociamos acuerdos de armamento. Lo cual tiene sentido. Tiene sentido hacerlo porque… si vemos cómo las armas nucleares afectan la forma en que calculamos las decisiones políticas, entiendes por qué es tan importante que un Estado autoritario que ya reprime a su pueblo sería aún más peligroso si tomara la decisión política de adquirir un arma nuclear. No es solo cuestión de… Y digo decisión política porque hasta ahora, como Irán sigue siendo signatario del TNP… Incluso esta administración todavía dice estar abierta a volver a restaurar el JCPOA bajo… lo que se les haya ocurrido. Pero si ese Estado autoritario tiene entonces un arma nuclear, es más peligroso no solo para su propia gente, sino por el tipo de consecuencias, la carrera armamentista que puede desencadenar. Lo siento, ¿qué?

Talia Baroncelli:

¿Una carrera armamentista regional también con Arabia Saudita?

Assal Rad:

Exactamente. Así que esa es la línea que hemos escuchado hasta ahora de la administración Biden, que es, incluso si continuamos las negociaciones, eso no cambia el tema de los derechos humanos. Todavía vamos a ir tras los actores y responsabilizar a las personas que violan los derechos humanos. Pero por otro lado, incluso con lo peor de lo peor… Estas son sus palabras. Incluso con lo peor de lo peor, mantenemos acuerdos de armamento. Y así se está entendiendo el JCPOA, al menos eso entendemos.

Talia Baroncelli:

Así que básicamente todavía hay canales de comunicación diplomáticos abiertos, pero tal vez no sean tan directos como bajo la administración de Obama, cuando…

Assal Rad:

En realidad, no lo han sido, ni siquiera antes de las protestas, porque la administración Biden no retornó al acuerdo. Se habla mucho, a veces, de miembros de la administración de Biden que dicen: “Irán debe volver al acuerdo”. Irán no se fue. El que abandonó es Estados Unidos. Y así, mientras que en 2014 y 2015 vimos fotografías de Javad Zarif y John Kerry hablando, aunque había negociaciones directas entonces, porque EE. UU. no era parte del acuerdo, no son parte de las negociaciones directas. Así que ha sido indirecto todo el tiempo desde… Creo que las negociaciones llevan algo así como 16 meses, pero básicamente desde abril de 2021, que fue cuando comenzó la primera ronda de negociaciones. No han sido directos, y obviamente la diplomacia funciona mucho mejor si puedes tener conversaciones directas. Pero eso no ha sucedido todavía.

Talia Baroncelli:

Fue la piedra angular de la campaña presidencial de Biden que EE. UU. se reincorporaría al JCPOA. Pero ¿crees que dijo esas cosas de mala fe o simplemente cambió de opinión en algún momento, quizá para quedar bien con Arabia Saudita y para aumentar la producción de petróleo, o qué crees que pasó?

Assal Rad:

Es difícil estar segura de cuál era el pensamiento de esa person, obviamente no lo sé. Pero mirándolo, al menos desde fuera, el presidente Biden, cuando era candidato, e incluso antes, la primera vez que escuchamos a Biden hablar de las políticas de Trump sobre Irán en 2017, justo antes de que Estados Unidos abandonara el acuerdo. Porque Trump no paraba de decir que odiaba el acuerdo y quería salirse, Joe Biden advirtió desde 2017 que era una decisión terrible y no debíamos hacerlo. En 2018, cuando EE. UU. se retiró, criticó duramente a la administración Trump, y lo hizo obviamente por muchas cosas, pero específicamente sobre el acuerdo con Irán. Biden, antes de que Blinken fura secretario de Estado, todos los funcionarios de Biden fueron extremadamente críticos con esta decisión de los EE. UU. bajo la administración Trump. Teóricamente habría tenido sentido, y algunos defensores de la diplomacia que apoyaron la campaña de Biden instaron a la administración de Biden a tomar medidas antes en su administración porque Irán iba a tener elecciones en junio de 2021. Y este siempre fue el miedo. En este momento tenemos una administración moderada y favorable al compromiso en Irán. Este fue su logro principal, el JCPOA en 2015. Y era mucho más probable que volvieran al cumplimiento si EE. UU. volvía al acuerdo de una manera que fuera más eficiente que lo que hemos visto. Precisamente lo que sucedió con la administración Raisi, que, si bien ha dicho que quiere volver al cumplimiento, si todas las partes vuelven al cumplimiento y hay ciertas garantías, ese es realmente el final de la diplomacia entre Occidente y esta administración. Y han recalcado que no están mirando a Occidente, están tratando de actuar conjuntamente con sus vecinos de la región, con China, con Rusia. Es un distanciamiento de los Estados Unidos lo que vemos con esta administración.

Creo que eso es parte de lo que tiene que considerar cualquier político estadounidense. Biden tenía muchas cosas con las que lidiar. La recuperación de la pandemia. Hay muchos problemas internos en los Estados Unidos. Que sé que la gente quiere ignorar, pero hay muchas preocupaciones en términos de división y lo que está sucediendo en los propios EE. UU. Entonces, está eso, pero también existe esta actitud predominante contra Irán dentro el discurso político,mdentro de la cultura popular, dentro de los medios, en los Estados Unidos. Eso influye en la forma en que vemos las políticas y explica a veces por qué nuestras políticas no tienen sentido. No tienen sentido para nosotros. No tiene sentido en términos de interés de seguridad nacional de EE. UU y la seguridad global haber renunciado al acuerdo, o haber tardado tanto en volver simplemente al acuerdo. Pero debido a que la actitud anti-Irán está tan extendida dentro de nuestra política, eso es lo que entienden por costo político. Es muy interesante. Tendría un costo político para Biden volver al acuerdo. Esto a pesar de que una mayoría bipartidista de estadounidenses apoya un acuerdo. Bipartidista, eso significa partidarios de Trump y partidarios de Biden. Entonces, es interesante si piensas qué significa el costo político. Costo político en Washington, DC. No el pueblo de EE. UU., porque no quieren una guerra con Irán. El pueblo lo apoya. Pero la retórica de Washington tendrá un costo político, especialmente si consideramos que Israel, que es un aliado clave de EE. UU. y ejerce una considerable influencia, también está en contra del acuerdo.

Así que hay muchas posibles explicaciones, pero es frustrante para las personas que apoyaron su administración y pensaron que él en realidad volvió al acuerdo desde el principio, y no fue así.

Talia Baroncelli:

Te he oído decir en el pasado, en una de nuestras conversaciones anteriores, que la élite estadounidense, especialmente el Partido Republicano, es quizás más dogmático que el iraní en lo que respecta a estos temas. Son imágenes equivalentes.

Assal Rad:

Hablamos de línea dura en Irán, los llamamos halcones en los EE. UU. Básicamente son lo mismo. Estas son las personas que nunca quisieron un acuerdo porque prefieren este tipo de statu quo de confrontación. Pero ninguna de las dos situaciones refleja la voluntad de la población, al menos en ese momento. En el momento en que se llegó al acuerdo, vimos escenas de iraníes celebrando en las calles, y el 70 % de los iraníes acudieron a las elecciones de 2017 para reelegir al Gobierno de Rouhani. Siempre digo que, aun si Raisi gana en 2021 con una participación de votantes extremadamente baja para Irán… 2017, el 70 % de los votantes votó, 2021, creo que es algo así como el 48 %, y quizá menos aún, porque muchos de los votos fueron votos en blanco. Esa es la elección. Es casi un boicot a la votación. Entonces, Raisi es quien se postuló contra Rouhani en 2017 y perdió por millones de votos. Así que el clima político en Irán también ha cambiado a lo largo de estos años, en parte como consecuencia de políticas que no funcionaron, cosas que no funcionaron de ninguna manera, nada ayudó. Su situación ha empeorado continuamente.

Talia Baroncelli:

Bueno, en el caso de Raisi, ¿crees que la gente específicamente no salió a votar porque se sentían completamente desilusionados y no pensaron que él realmente querría trabajar con Occidente y que Occidente no podía reincorporarse al acuerdo con Raisi al mando? ¿O crees que hay algo más que explique eso?

Assal Rad:

Creo que la gente no salió a votar por una combinación de razones. Sentir que el sistema no los representa, que no funciona, no les ayuda, no les sirve. El hecho de que… El proceso electoral en Irán no es totalmente democrático. Los candidatos siempre son aprobados por un organismo no electo, por lo que es antidemocrático desde el principio, pero tiene elementos democráticos, deberíamos decir. Pero en 2021, este proceso de aprobación se exacerbó. Nadie podía postularse. Así que fue casi un caso de elección a dedo. No hubo nada que se parezca a una elección real. Eso también. En realidad, no había opciones. Estaban decepcionados con el sistema político en general. Y puedes entender, después de todo lo que han pasado, con el COVID, las sanciones, con protestas reprimidas, que realmente no tenían ganas de salir a votar. Pero eso también es una decisión política. No solo tienen agencia cuando votan, también tienen agencia cuando no votan.

Talia Baroncelli:

Eso en sí mismo es un acto político también.

Assal Rad: