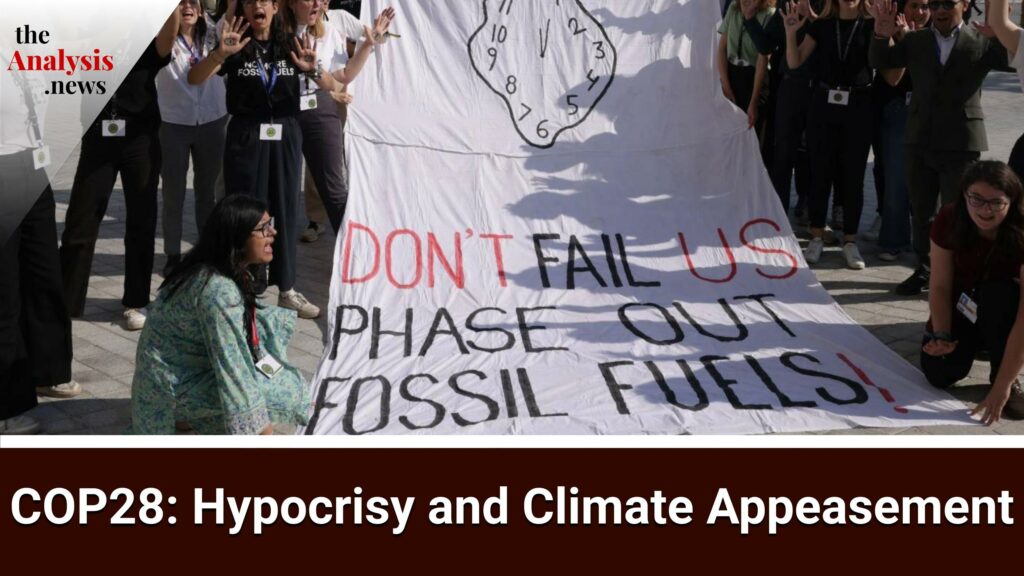

Patrick Bond, political economist, Professor of Sociology at the University of Johannesburg, and Director of the Centre for Social Change, expands on the first Global Stocktake produced at COP28. He criticizes the document’s weak language of “transitioning away” from fossil fuels, which he says is a distraction from the need to phase out fossil fuels outright. Sanctions such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) to prevent carbon leakage were removed from the GST in the name of promoting global trade, another aspect Bond problematizes. He also addresses the BRICS+ divided approach toward Israel’s bombardment of the Gaza Strip.

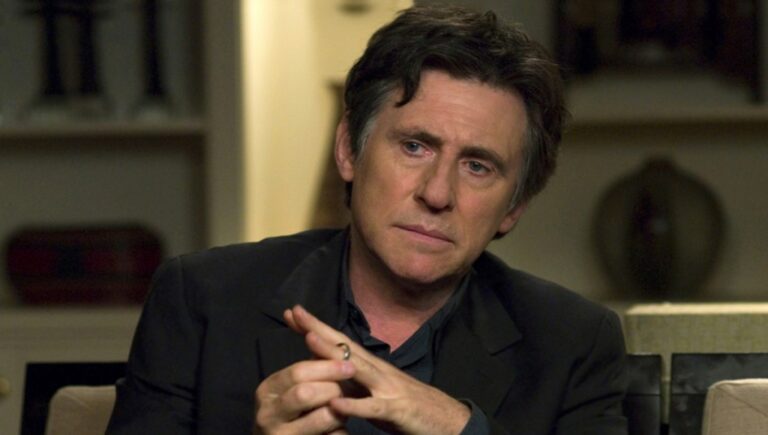

Talia Baroncelli

Hi, I’m Talia Baroncelli, and you’re watching theAnalysis.news. I’ll shortly be joined by political economist and friend of the show, Patrick Bond, to speak about the final document produced at COP28, as well as the divided position of BRICS countries vis-à-vis Israel and its ethnic cleansing of the Palestinians.

If you’d like to support the work that we do, you can do so by going to our website, theAnalysis.news, and hitting the donate button at the top right corner of the screen. Get onto our mailing list and like and subscribe to the show wherever you watch the show. Help us beat the algorithm on YouTube by liking and subscribing there as well. See you in a bit with Patrick Bond.

Joining me now is Patrick Bond. He is a political economist and professor of sociology at the University of Johannesburg, where he directs the Center for Social Change. He is also the author of the book BRICS: An Anti-Capitalist Critique, which he co-authored with Ana Garcia. It’s a pleasure to have you back on, Patrick.

Patrick Bond

Thanks. Great to be with you as ever, Talia.

Talia Baroncelli

The UN climate conference, COP28, took place over a period of two weeks, and it was presided over by UAE Sultan Al Jaber, who is coincidentally also the ADNOC oil executive and co-managed by South Africa’s Environment Minister, Barbara Creecy.

The final document they produced at COP is known as a global stocktake. It’s meant to assess whether the commitments in the Paris Agreement are being implemented. One of the most significant lines of this stocktake is the following commitment, and I quote:

“Transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems in a just, orderly, and equitable manner, accelerating action in this critical decade so as to achieve net zero by 2050 in keeping with the science.”

What do you make of this weaselly statement?

Patrick Bond

Yes, it’s very good to be able to pick apart and dissect the power relations, the institutions, and even individuals who’ve been putting pressure on the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Conference of the Parties 28— sometimes we keep it short— the Conference of Polluters 28, that this institution has again failed the planet. It’s usually in two ways. One is to fail to cut emissions in fossil fuels specifically. The other is to deny liability for the pollution, the so-called polluter pays, in which the emissions that have been causing climate catastrophe, mostly historically, number one, United States, number two, China, Russia, India, and Brazil. Some of the BRICS countries, Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, are also in the top 10, including the U.K. and Germany. What they really want to do, and especially this time, the OPEC, Oil-Producing Exporting Countries, the big oil cartel led by Saudi Arabia, wanted to avoid a formal commitment to phase out both oil and gas. They’re willing to phase down coal, so that language is there. But even methane gas, which later on in the document is acknowledged to be one of the most crucial areas, especially for methane leakage to cut right away. You can see that the wording transitional is, as you say, it’s a weasel word because what they’re then saying is that a transitional fuel to get you out of oil and coal is gas.

The contradictions and internal conflicts that we can see within the climate policy elite are screaming out, but no more so now than at a conference hosted by the UAE, which itself, under Sultan Al Jaber and his Abu Dhabi National Oil Company, played a very, very pernicious role in the COP and has actually openly acknowledged that they want to continue their own expansion of their oil and gas, and they’re going to probably do a 50% expansion in the next seven or eight years before 2030. Then they’re at the peak and then finally go to net zero by 2050. It’s all a fair bit of mumbo jumbo, isn’t it?

Talia Baroncelli

Yeah, it is the first document produced by a COP that actually does identify fossil fuels as a culprit. Do you think that’s a declaratory acknowledgment, and it doesn’t really have any teeth?

Patrick Bond

Yes, that’s the dilemma because the weasel words include, especially for coal, the term “abated.” If you want to abate your coal, then you basically go through one of the loopholes, and you can continue. The unabated means you haven’t put in these gimmicks like carbon capture and storage. That, as the Marshall Islands Envoy, Tina Stege, said, “It violates what we really, even the Paris Climate Agreement, acknowledged; that a 1.5-degree rise by the end of the century,” even though we will probably hit it this decade, “is not negotiable, and it means an end to fossil fuels.” It’s where the gas loophole comes in as transitional and where abatement of coal is allowed. That is through trying to draw in the carbon that’s emitted through sequestration and store it underground, that we can see the danger of this and the need to, I think, delegitimize the process because it’s not going to stop here.

Next year, it goes to Azerbaijan. That was a hotly contested choice for the hosting of COP29 a year from now. Azerbaijan and Baku, the capital city, are absolutely carbon addicted, one of the very worst in the world, and very connected to, particularly Vladimir Putin, who didn’t want to see a member of the EU host COP29. You could argue that in 2025, it will then go to Brazil, where Lula da Silva, who has a strong environmental minister, Marina Silva, they do want to host it in the Amazon, in Belém, and make some real progress. Between now and then, I think the activists out there have to understand that looking globally for solutions from the Conference of Polluters, what I would call this global stocktake document, oil jabber, in honor of Al Jaber, that really isn’t going to take us anywhere.

There’s a debate. Bill McKibben, the great 350.org founder, has argued, and we’ve had some email debates about this, that you can at least use that transition out of fossil fuels for your activism. I hope so. But as I said, the loopholes, the weasel words, are really debilitating. It may be that, like most of the COPs, the more we put our, let’s say, faith in leaders, not only Al Jaber, but South African Barbara Creecy, the Environment Minister, the more we put our faith in these global climate policy elites, the less we do activism to directly halt the emissions and block fossil fuel projects and try to make other changes through, as Naomi Klein puts it, “blockadia,” that’s really where the future lies. We shouldn’t be distracted by these global processes that are really so reactionary.

Talia Baroncelli

You mentioned the small island nations, the Marshall Islands, for example, said that the global stocktake has been a death sentence for them, given that any warming that goes beyond 1.5 degrees will inevitably lead to the destruction of their economies given that they’re island states, so they’re highly vulnerable to any change in water levels. They also said that the decisions to adopt the global stocktake or to endorse it were made without them even being in the room, without their ability to consent to it or legitimize it. Do you think this was done intentionally to avoid having their input?

Patrick Bond

Well, I think that’s a good question because Samoa had a very strong lead negotiator, Anne Rasmussen, and she was furious with Al Jaber, the head of COP. She said, “You gavelled the decisions, and the small island developing states were not in the room. It is not enough for us to reference the science and then make agreements that ignore what the science is telling us we need to do.” They were the small island states that were really faced with the extinction of their island homelands. They were simply having a caucus and preparing. In that space, Al Jaber, on Wednesday morning, the last day, the day after it was meant to end, pushed it through. The tragedy is that the elites there did give her a standing ovation, but they also gave Al Jaber a standing ovation. It just shows the profound schizophrenia.

Talia Baroncelli

What do you make of the influence of the IMF in this particular document? There was an IMF panel while COP was going on with that of the IMF, George Abed, speaking about the need to ensure that there are no barriers to trade in this green transition, that there’s enough research and development and subsidies for research and development, a reduction of subsidies for fossil fuels, but that there should be no barriers or impediments to trade in developing some of these technologies. If I recall correctly, the carbon border adjustment mechanism tax was stripped away from the global stocktake, and this would put an additional tax on high-carbon emission products. What do you make of that?

Patrick Bond

Yes, indeed. CBAM, the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, was hotly contested. The IMF said that interference in trade should be avoided, even though the WTO, the World Trade Organization, has been relatively ambiguous. The leader of that institution, who is a Nigerian, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, said she wasn’t going to chime in on either side.

On one side, led by South Africa, by Barbara Creecy, the Environment Minister, is the position, particularly from BASIC: Brazil, South Africa, India, China; Creecy was able to get this position through the Africa Climate Summit, which occurred in September. That position is to take out these trade barriers, which are unilateral.

On the other side would be the Europeans. Now, you could call the Europeans, as I’m not unwilling to do, imperialist and protectionist, and yet they have a logic we have to be acutely aware of. They’ve got a carbon tax of sorts. It’s an emissions trading scheme. They give a lot of free credits. Those are beginning to wane. The price of that tax, it’s up and down. It was up to over $100 per ton of carbon emitted you have to pay on top of all the other costs in your production process. It’s now $85. It’s really zig-zagging because, like all financial markets, it’s an incredibly volatile way to handle something as important as putting a price on carbon. It’s a ridiculous way to do it, to be frank. But that price, $85 per ton today, is in contrast to South Africa’s carbon tax, which is around $30 U.S. cents per ton.

You can see this huge difference, which means if you want to cheat the E.U., you’re a company there, and you shut down your own, let’s say, steel or aluminum, petrochemical, or high carbon production system. There’s a variety of goods that are going to be immediately taxed, even cement. Instead of having foundries making steel in Europe, you import them from South Africa, where a big Luxembourg-based company, ArcelorMittal, run by an Indian, Lakshmi Mittal, has set up a number of the foundries here, and we export a fair bit of steel, aluminum, petrochemical, and other high carbon inputs. If we do that from South Africa with a very low carbon tax, there’s carbon leakage, which means that the Europeans will be importing what they’re trying to ban or put a high price on in Europe. That’s what the European steel producers are saying, “We’re going to need some protection here.” I think that’s actually perfectly reasonable, even though it is imperialist and protectionist. But it does reflect, doesn’t it? South Africa and the other countries affected, there will be a couple of other African countries, basically South Africa, but certainly China and Brazil, as they produce high carbon-intensive output from embedded energy that comes from coal-fired power plants, well, they’ll be subject to a tariff, and that was also, by the way, the United Kingdom announced, and the United States is going through similar debates about how to avoid this leakage or the cheating by moving the problem around.

I think there is a logic, which I can’t deny from imperialism, but the sub-imperial powers, the ones I mentioned, they’re very angry that this may mean that they’re heavy industries, which are actually mostly Western, mostly nationals: ArcelorMittal, Luxembourg, BHP Billiton, the major aluminum company that’s from Australia, it’ll be Western car companies from Germany, Japan, and the U.S. It’ll be a partly U.S.-owned petrochemical company. Those will be the main ones that will be adversely affected by the CBAM.

Now, to come back to the IMF, the IMF has this terribly confused role because Kristalina Georgieva, the current managing director, did replace Christine Lagarde. In that replacement, Georgieva wanted very much to put her own mark on the institution. She’s an economist. She comes from Eastern Europe. There was no hope of getting a third world leader of the IMF given these historical apartheid types of rules: the Europeans run the IMF, and an American runs the World Bank. What she did was to start saying I care about climate, and they started to count the damage of climate. You’re right that, on the one hand, they have their standard neoliberalism applied to trade to try to get climate out of trade in the way they’re not approving the CBAM.

However, what they do acknowledge is that there’s, let’s say, a subsidization that’s both explicit where, say, oil companies are getting subsidies to go and drill; the U.S. is notorious. But also, they are implicit because if you’re not taxing carbon at the right rate, you’re basically allowing them to pollute without penalty, without paying. That implicit subsidy is most of what they say is $7 trillion per year. However, when we look at that with a little bit more critical perspective, currently, they’re pricing the carbon at $65 a ton. I think not $85 as the E.U. emissions trading scheme, or even the $185 that the United States would like to put on, or at least the Environmental Protection Agency currently is $51 a ton. But actually, some of the research that I trust much more from scholars who do environmental economics with a much greater sense of the feedback loops, and their price is $3,000 a ton. You can see if you’re getting into this game of pricing, well, I wouldn’t go with the IMF, which is very conservative on this. Where we do these debates, Talia, in environmental impact assessments or trying to go to our courts, we haven’t yet found in a place like South Africa, the ability of our technocratic elite to make a price on carbon really change behavior. That’s the dilemma. We’d like a price like the carbon border adjustment mechanism, a tax on imports to really change the way our own output, for example, our steel and aluminum, is made. Because it is possible to make it with renewable energy, we have huge reserves of sunlight and wind and lots of energy storage potential. But the fact that we don’t have a tax means there’s no real incentive to make any change. The continual pollution of a country like South Africa, based on the multinational corporations that do high carbon exports, is a problem that I think our own climate justice movement cannot achieve sufficient power to correct without the sanctions, that is, climate sanctions, the carbon border adjustment mechanism.

It’s a tricky situation because when do you want Western imperial power to side with you as a progressive? Rarely, if ever. There may be cases. There may be cases where, in the United States, Ronald Reagan was overturned on his veto of sanctions against apartheid South Africa. The U.S. Congress actually sided with the black majority in demanding sanctions. There are cases where I think even imperialists need to be, let’s say, positioned so that the damage that they do ordinarily, that is, by importing high-carbon products, can be mitigated. I think these sorts of sanctions have to be looked at with an open mind.

Talia Baroncelli

Would you say that’s why Jeremy Hunt, the head of the British Exchequer, decided to also impose this carbon tax?

Patrick Bond

Yes. Now, all of these are, as you say, proposals because they will require more debate, discussion, and implementation. In the case of Europe, the European Union says from October this year, they’re already doing the bean counting. They’re beginning to find out, well, how much should this import tax be and who’s going to be liable for it?

In the case of Europe, they will only kick in with pricing in 2026. In the case of Britain, what Hunt and the Treasury said, “Let’s do this in 2027 starting with steel.” But I anticipate this to be the more environmentalists will pick up the pressure. It may be difficult in the U.S. because of potentially Donald Trump as the President again. He obviously won’t care a damn about having a high carbon tax. He’ll reduce it, as he did from the Obama years, from $51 back to $1.

Now, that means I think we’ve got a little bit of time here to make the case that the Europeans, the Brits who do the CBAM, actually owe those who are affected a just transition, grant-based reparations for the damage that will be done. This is the case we need to make for not just loss and damage when there’s a terrible climate event, as we saw in the Sharm el-Sheikh COP27. There’s a lot of lobbying to fund and help compensate countries like Pakistan last year, a third of it underwater. Many terrible climate catastrophes this year.

In South Africa, the worst was 500 people killed in a rain bomb in 2022 in Durban. Now, there are plenty of loss and damaged cases, but the big question ultimately will be whether a strong, just transition can be demanded from the West so that grant funds will help to, let’s say, mitigate the damage.

Now, we do have a very weak version of this. Here in South Africa, the pilot project came from the U.S., U.K., France, Germany, the E.U., and the World Bank playing a role. It’s a very weak version. It’s called a JETP, a Just Energy Transition Partnership. It’s what we would call a carrot, along with what we were describing, the CBAM; it is a stick. The carrot is to incentivize these just transitions to decarbonize, to get rid of our coal-fired power plants earlier than we would when they’d break down and fall apart. We should be doing that, and there’s a huge debate about how fast to do it. What they fail to do is to offset the damage to communities and workers that have become coal-dependent.

Similarly, we have a JETP, which is a stick, but it’s not really working very well. For example, Europe says methane is green and nuclear is green. We haven’t yet found ways that the stick can be sharper and harder and that the carrot can be nutritious. Currently, it’s quite rotten. That carrot and stick, let’s say, the combination is what I think our global climate justice movement has to begin to work together because the elites are doing the deals behind closed doors and making a big mess of it.

As I said, Barbara Creecy, particularly our Environment Minister, who was the co-author of the global stocktake, the final document, and one of those officials was the co-chair of the Loss and Damage Fund with a Norwegian official, a Danish official was the co-chair. We’re really looking at, unfortunately, global elites who are siding with Al Jaber instead of delegitimizing and kicking them out. Barbara Creecy is also very much subject to the power of the coal and the new methane gas lobby here in South Africa. Those are the sorts of dilemmas that really speak to a need for profound, radical political challenges from the base.

Last Saturday, December 9, we saw 28 protests along our beachfront in the Indian Ocean, Atlantic Coast, because they’re now getting approvals from Barbara Creecy for Total, for Shell, for a local ally called Impact Oil run by a man called Johnny Copeland. These are the figures who are getting the thumbs up as we speak to go and drill for more gas and oil. We really need much more radical political movements from below, and maybe changes of governments to get rid of these kinds of policy elites.

Talia Baroncelli

Barbara Creecy doesn’t seem to be the one to oppose any approval of these additional oil and gas offshore drilling contracts with companies such as TotalEnergies, as you mentioned.

I do want to ask another question about the Loss and Damage Fund, because the Loss and Damage Fund was discussed very much in Sharm el-Sheikh during COP27. I think COP28 establishes the fund and establishes the World Bank as the overseer of the fund. The World Bank is, of course, led by business-friendly Ajay Banga. What do you make of the fund? Is it really worth its salt? So far, it seems like one of the biggest emitters in the world, the United States, is only committed to contributing 17.5 was it billion or millions? I can’t remember how much. [crosstalk 00:23:32].

Patrick Bond

I wouldn’t be surprised. Yes, that’s a very acute observation about, number one, who’s responsible for the crisis, and are we going to let them be in charge of cleaning it up? Why aren’t we charging them more, especially the United States? But I would even add the BRICS because it’s not just the West that are climate debt denialists. That is, they’re refusing to acknowledge the polluter pay. That’s even in their own national environmental legislation. If they make a mess inside the U.S., then there’s a Superfund that the polluters contribute to to clean it up. That’s what we need, a global Superfund for paying those reparations for the climate catastrophe.

John Kerry, the U.S. climate czar, testified in the U.S. Congress in July that he just absolutely denied liability. He made it very clear we explicitly removed liability from any discussion. In fact, it was in the Paris Climate Agreement that if you sign on, you forgave the West and the BRICS for their high emissions. That’s one crucial dilemma. Of course, that means that the U.S. can give merely tokenistic support, $17.5 million. The amounts that will be needed will be in the $100 billion-a-year range; that’s the cost of the damage, especially because the insurance that the north provides to, say, mansions on the South Florida Coast is just not available. The 60% of the damage done under the prior, let’s say, catastrophes that have been measured by Christian Aid in the north, 60% is insured, but only 4% in the south. We desperately need that loss and damage fund, especially for countries that not only then need to rebuild after terrible climate catastrophes, especially cyclones, floods, and high winds, but also have to build back much better. They have to have stronger stormwater drainage, better irrigation systems, and tougher roads and bridges that can withstand terrible climate catastrophes.

Now, the U.S. is amongst those that are most affected because they continue to have ever-worsening hurricanes, tornadoes, droughts, and water shortages. They’re putting their money back, as the Inflation Reduction Act does, in various ways for renewable energy investments and for some of this loss and damage. But it is the ultimate hypocrisy of an absolutely irresponsible global citizen that the U.S. is only paying a little bit. Then they’re pressuring, and of course, the South Africans and some of the BRICS countries agree that the World Bank becomes the manager. When we’ve seen the World Bank manage these funds, their value systems, they are the single biggest historic financier of fossil fuels. Even still to this day, we see in South Africa an LNG, liquefied natural gas terminal being financed since the early stages by the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation. Again and again, we find a terrible legacy that continues of World Bank fossil financing.

I think also the general neoliberal tendencies of these funds in which lending is desired, in which the private sector is brought in, and in a sense that subsidies go to reduce the risk. We’re seeing a Wall Street consensus emerge away from what normal social democratic states do, which is when they see a crisis, they are often pressured to move in and solve the problem using grants.

Instead, now, we’re getting blended finance and public-private partnerships and all manner of climate financing gimmicks. It’s just appalling because the hard currency loans that, for example, we have on our JETP, 97% of our so-called concessional finance from the West is in dollars, euros, and pounds; that means we’re paying in the hard currency. But as our currency falls, of course, the effective interest rate goes up to the point where it’s unaffordable. It just layers more debt.

These are conditions, even last week, Ethiopia, a crucial country, one of the new BRICS+ members, very much subject to climate catastrophes, has gone bankrupt. Before that, it was Ghana and Zambia. We’re seeing even countries that have been considered to be stars of the 2010s and economic activity face of the 2020s, lower commodity prices, higher interest rates from 2022, the inability to pay the debts, and now the only solution from the global elites is more climate debt piled on top.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, you mentioned the BRICS’s problematic position here, especially given that they’re huge carbon emitters. I’m thinking specifically now of India, for example, because India was not endorsing the global stocktake commitment to phase out unabated coal use. That’s probably because 73% of power generation in India is based on coal.

There are quite a few stakeholders in India that would argue that countries such as India and other countries in the Global South, because of the legacies of colonialism and other forms of exploitation, have not been able to develop industrially or economically at the same rate as other countries in the Global North. They should be allowed to emit more in order to reach those levels of advanced industrialization and have greater GDP and economic growth. What do you make of that argument? Is that an excuse to continue emissions and to potentially ensure that the elite are profiting from those developments?

Patrick Bond

Yes, absolutely. There was a great strategist connected to Greenpeace, India, and some of the organic social movements there, Praful Bidwai. They put a critique out a dozen years ago saying this is so-called hiding behind the poor. That is to say, in making a case, as Narendra Modi does, that he’s really for the people and you need to have much greater increases in energy availability. Actually, the way in which the coal-fired power plants are being rolled out in India, still in China, benefits elites and exporters and high carbon producers but doesn’t ever solve the problems, the energy problems of the poor.

The same is true in South Africa. We have lots of this “talk left, walk right,” or “talk green, walk dirty,” hiding behind the poor. I think that’s where the really interesting problem of the BRICS, who claim to be multipolar, and we’ve talked about them at length, making an advertisement that if Western corporate power and United States power over multilaterals is suffocating and we need a new system of balancing with the new emerging economies like China and India, some of the most obvious ones.

Nevertheless, in reality, in places like the UNFCCC, as well as the World Bank, the IMF, and the WTO, you’ll find the most reactionary forces in both the West and the BRICS co-hearing. Again, the two crucial points for them both are not to cut the emissions and the fossil fuel use. Firstly, they do not acknowledge their reparations and liability. They refuse polluter base.

Those are the two areas where again and again, especially since the 2009 Copenhagen Summit where Jacob Zuma, our South African President, joined Wen Jiabao from China, Manmohan Singh from India, and Lula from Brazil. Barack Obama from the U.S. barged into their meeting. They basically set in motion this process by which the emerging economies can complain, but they’re basically satisfied with the deal. Even Vladimir Putin said he was absolutely satisfied with what came out of the COP28.

I think it’s this awful dilemma where we keep talking about the North and the South or the developed and the developing, but we’re failing to acknowledge that between imperialist climate policymakers and the vast majority of the world as victims, stand as sub-imperialist, [inaudible 00:32:07] elite, were perfectly assimilated into the system. We’ve seen that as well, notwithstanding huge contradictions in the way geopolitics plays out, whether that’s in relation to Ukraine or the Russian invasion.

But particularly, it’s on display because of the four new BRICS members who are from the Middle East. Three of them are strong U.S. allies: Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. With UAE having in 2021 signed the Abraham Accords, and of course, with Egypt long having normalized relations with Israel. In the Israeli genocide against the Gazans, of course, it’s only Iran that, perhaps with their Houthie rebel, maybe it was Hezbollah, is on the side of the Palestinians in a concrete way. In the BRICS discussions, you’ll see just how schizophrenic and ineffective this so-called multipolar alternative is because it made no dent whatsoever in the power relations. Indeed, maybe when a Houthie missile is fired against Israel, it will actually be Saudi Arabia doing the first line of defense on behalf of Israel.

It’s an extraordinary period of fluidity and the inability of BRICS to stand up and really become an anti-imperial force when the world needs it so badly instead of behaving largely as sub-imperialists.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, why do you think there is no united front on the part of the BRICS or the BRICS+ with the additional Middle Eastern countries that have just joined it? Is it because their primary interest revolves around economic interests, and they’re maybe not able to have some solidarity with even the Palestinians? For example, if you look at Israel’s ongoing ethnic cleansing and bombardment of the Gaza Strip.

Patrick Bond

Yes. We used to have a very good view of this in South Africa, and it’s partly economic because we have about $500 million worth of trade. It’s a relatively balanced trade. We export a fair bit of coal, diamonds, and grapes to Israel, and we get bits and pieces back. But the roughly $500 million here is important, and that’s why, in spite of some good rhetoric from our government, they do declare Israel to be an apartheid state. They do go to the International Criminal Court with that complaint. They’re even using genocide. Indeed, the big challenge will be to invoke the Genocide Convention if they’re serious about it and also to expel the Israeli ambassador.

Currently, the Embassy in Tel Aviv, South Africa’s embassy, is closed, but we haven’t shut it down. We haven’t withdrawn it. Secondly, we’re looking for more BDS support because aside from one meeting in which Muslim and Palestine solidarity activists pressured the government to withdraw Israeli, South African, or part-Israelian that could have dual citizenship, or they go from some of the Zionist schools and they serve in the IDF. That’s now going to be perhaps regulated. It’s not meant to happen. It’s been happening for years.

There’ are also some important relationships between the ANC, the ruling party’s main funder, the name is Ivor Ichikowitz. He’s the single largest funder, publicly disclosed this year. He has an office in Tel Aviv for his defense industries, which is called Paramount Group, and they have a joint venture with Elbit, the main Israeli arms company, to supply very brutal Ecuadorian army with sophisticated military vehicles.

Now, these are the sorts of things that you could say in a microcosm, not nearly as big as what the West does, but certainly South Africa has had important relationships. It goes back to the joint development of nuclear weapons technology in the late 1970s.

There are relationships of that sort. India, most of all, because Modi has always been very close to Netanyahu, and they’ve had very strong military relationships with the Israeli companies.

In addition, I think the dilemma for the BRICS is that they haven’t worked well geopolitically because of very important divisions. That was very obvious with Lula not entirely supporting the Russian invasion, voting against Russia in the General Assembly, South Africa having lots of ambiguities. But if we look forward, Russia is going to be hosting the BRICS, and what they’d like to do is expand the membership, and that’ll be in October this year.

The dilemma for them is if they were going to take amongst the 21 countries that applied this year, only six were chosen, one of which Argentina dropped out because of the election of Javier Milei, the right-winger, who didn’t want to have any part of BRICS. There are these five countries that are coming into the BRICS. Now, last week I spent a couple of hours with the BRICS Bank Vice President, and that’s the second huge contradiction. As you say, it is an economic one because this man named Leslie Maasdorp, a very bright man, I once worked with him on writing policy papers for Mandela’s government. He is very convinced that the Western credit rating agencies are who he must answer to as the chief financial officer.

Talia Baroncelli

Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s, those companies.

Patrick Bond

Exactly, Talia. If you know these countries that are under the thumb, which include Western countries, even the U.S. has been under the thumb of the credit rating agencies and had its debt rating downgraded. Obviously, they go through scares every so often where the bills may not be paid in the U.S. government. But the main point about that is we have a bloc within the BRICS. It’s mostly the finance ministers, central bank governors, and bankers who circulate amongst them. There’s a revolving door between our own banks and these officials. They really are so pro-Western that if you want to raise something like de-dollarization inside the BRICS, you’re not going to go anywhere with it, as we found in August.

It may be that in October next year, Russia is so desperate because it’s been shut out of the big international payment system, Swift, that they want to now go forward and see if they can do something. Maybe it’ll be Yuan based, but even the Renminbi, the main way the Chinese trade abroad, is very difficult to use because they retain strong exchange controls. The relationship between India and Russia, where there’s a huge trade deficit because India has been taking in so much Russian energy, the Ruble and the Rupee are terribly imbalanced.

So all of those processes that we’ve chatted about before in which de-dollarization has run aground now, I think does exactly confirm your point. Economic interests within the BRICS and ambiguous interests in relation to the Israeli links mean we may not see much potential for the BRICS to do anything to put pressure on Israel to stop the genocide. Here in South Africa, we’re on the front line because we have such a good experience with boycotts, divestment, and sanctions against apartheid, which was a crucial part of getting rid of official racism here to have international sanctions. That’s what we’d love to see happen, maybe even the Swift system in Belgium, which has a relatively more progressive European leader opposed to Israeli genocide. That would be the campaigning lessons I think we would take. BDS is terribly important now to pick up against Israeli genocide, and then as well to cut these relationships and to call Israel genocidal in that convention. These are the sorts of things our own government, even under Cyril Ramaphosa, is willing to use words like genocide and apartheid.

I’ll point out one last aspect of this. Mandla Mandela, the grandson of Nelson Mandela, has been leading the cause inside the African National Congress as a member of Parliament for this party to say, “Ramaphosa, stop mollycoddling the Israeli apartheid regime’s genocide.” There’s very tough language from Mandela’s grandson. It shows you just how far, even after good rhetoric from Pretoria, but how far we have to go to turn that into reality.

Talia Baroncelli

I do want to ask you, though, there are a few members of Hamas who attended a meeting with Mandla Mandela in South Africa. How problematic is that?

Patrick Bond

Well, certainly, the South African government said we have nothing to do with that. They met the South African Jewish Board of Deputies in the South African Zionist Federation last week. In a sense, I wouldn’t say apologetically, but they said, “Look, we don’t have any control over whether Hamas comes in and out of the country but don’t worry, we didn’t host them. We’re not meeting with them.” At one point, there was a phone call between the foreign minister here, Naledi Pandor, and Hamas. We don’t really see any sense in which there’s any recognition of Hamas.

There is a recognition of Fatah and the Palestinian Authority, and that’s slowed us down enormously because the Palestinian Authority has opposed BDS, except for goods produced within the occupied West Bank, the territories.

The main point about Hamas here is it has a relatively more symbolic role. What it has done, because it was a political wing of Hamas based in Qatar who came; three of their officials went to a meeting that Mandla Mandela hosted, raised the profile of the need for solidarity. But it has left, especially those who come from more secular traditions like BDS who are non-sectarian and non-religious in their support for Palestine, with the need to continue to hit the streets and protest. Every day, sitting around as a BDS researcher looking at WhatsApp streams and activities coming, it’s quite inspiring. A thousand people just immediately convened at the Zara store last week to protest once it became known there are Israeli connections. We find many little micro-targets all over the place. I think the big question is, can we keep these energies going during this break that we’re on in South Africa at the moment, and then really come out with a more coherent strategy that it’s the state and capital, and particularly the military relations like the soldiers that go over or the paramount groups’ connections to Israel.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, looking back over this past year, 2020-2023, there have been so many tragic and destructive developments. Obviously, the ongoing war in Ukraine, but of course, what’s going on with Gaza by Israel is not only genocide, but also ecocide. They’ve been doing all sorts of environmental destruction to the Gaza Strip and also illegal settlers, removing olive trees, destroying olive trees in the West Bank. There are, of course, horrible developments there. Is there anything that perhaps is going in the right direction that gives you a bit of hope or something to latch onto for enacting some change?

Patrick Bond

Obviously, with global elites having failed, they even have a term for their failure. It’s quite interesting, Talia, the “polycrisis,” you find that in the World Economic Forum, and their inability to address everything from pandemic management to the climate catastrophe and biodiversity loss and great species extinction and economic inequality and turbulence, financial crashes and geopolitics and all of the extreme, let’s say, rising tensions and hardcore right-wing figures popping up everywhere.

The failure at the top reminds us of two things that I think we always need to keep in mind. In 1987, there was a similar thread ecologically, which was the Ozone hole growing, and the 1987 Montreal Protocol did arrive at a point where the cause of that, the chlorofluorocarbons were banned, and the ozone hole was subsequently stabilized. The second was the global fund to fight TB, AIDS, and malaria, which followed in 2002. The World Trade Organization agreed that medicines and public goods could be taken off intellectual property. Now, we lost that fight for COVID vaccines in 2022 in the WTO, but it’s a model in a sense of what a loss and damage should be and could be if we got a stronger set of, let’s say, states in the United Nations that had real interest in solving loss and damage, the climate debt, the reparations.

We need more activists like they had in the early 2000s, the Treatment Action Campaign, the ACT-UP group out of the U.S., and Médecins Sans Frontières at Oxfam. They played a great role then. That’s what we’re, I think, to turn to what’s more hopeful today, the return of pressure and global climate activists who are doing more and more direct action. I’ve seen places that are very coal intensive, like the Ruhr Valley of Germany, and you see the Ende Gelände and Letzte Generation, or you see Extinction Rebellion and No To Oil. You see all of these movements popping up, the ones in the United States that have indigenous strengths in water, defender, politics, but they’re also climate activists. All of these, to me, are the source of hope.

When we saw mass protests over a period now of two years that also went into the courts and began to slow down the offshore gas and oil drilling here. To me, that was one of the great ways that 2023 reminds us of the potential of grassroots power. The second is Palestine Solidarity to see the upsurge in anti-racism and anti-Zionism that has been so, let’s say, effective in putting Israel on the back foot in terms of how it tries to market and spin doctor its genocide so that only a few elites like a Joe Biden, Olaf Scholz, or Rishi Sunak can still stand with Netanyahu, someone like [Emmanuel] Macron walking away as fast as possible. Those, to me, reflect that the delegitimization of the global elites has been another part of what we’re about. The more we can put pressure to halt that genocide and to begin to roll it back and to find some way to make really concrete the “Free Palestine” slogan, the more that we hear from Palestinians about how we should be proceeding as the terrible carnage hopefully comes to an end. We can think about a longer-term plan. That’s what we need with both movements and, of course, to expand everywhere.

The World Social Forum is held in Nepal. There are going to be a variety of other sites around the world where people are going to gather and do strategy. What I’m hoping is that the upsurge of support for Palestinians and the upsurge of climate protests here in South Africa and around the world give me so much faith that they will begin to link themselves to each other and to link to all of the other issues where we desperately need anti-imperialist and, frankly, anti-sub-imperialist politics.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, not to disregard or belittle your reasons for hope, but if we look at the United States and Israel, they’re increasingly isolated internationally, and yet this international isolation has had very little effect in terms of policies on the ground. We just saw the General Assembly, for example, pass a resolution in which 153 member states called for the immediate cessation of hostilities and immediate ceasefire. Even Canada and Australia changed their vote and decided to vote for this resolution. Yet, due to the power imbalances of the global system and the UN system in particular, this has had very little effect.

Patrick Bond

Well, and even worse, you could say that looming over Joe Biden’s pro-Israeli stance and fossil fuel amplification because he’s setting up even more LNG export facilities in the Gulf of Mexico and more oil drilling in Alaska, behind him stands another threat, Donald Trump. Even a third-party potential candidate, RFK, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., has come out in a manner that’s absolutely imperialist in relation to Israel’s genocide. He’s all for supporting Israel.

Yeah, the political landscape looks absolutely grim, and yet the potential that the U.S. has for sudden increases in political pressure from below, like Black Lives Matter in 2020 in the midst of COVID, those sorts of potentials do surprise us as they have everywhere. We’ve had the upsurge of protests in North Africa and the Middle East, the so-called Arab Spring that seemed to have come from nowhere. Now, it was repressed, but I think that the rise and occasional victories of social movements, our Treatment Action Campaign, our students winning #FeesMustFall to get rid of fees on tertiary education for working-class students, social movements that win and demands for water, sanitation, and electricity, all manner of micro-struggles around the world.

We’ve had too many of them take the form, Talia, of popcorn where they pop up but then fall back without finding a coherent movement politics. I could at least just say that our independent left in South Africa is beginning to regroup. There’s a new movement that just formed last weekend called Zabalaza Socialism. Zabalaza, meaning struggle. There are those little indications that there is still a desperate need that’s recognized by our leading activists, a need for ideology and for transcending capitalist and, let’s call them in the silo, atomized modes of resisting the huge imperialist threat to humanity and making those issues as explicit as possible all the time and linking them together rather than being in a NGO mode where they’re all fractured and fragmented. That’s, I think, our challenge for the period immediately ahead.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, let’s hope we meet that challenge and are able to enact more change in 2024. Patrick Bond, thank you so much for joining me again.

Patrick Bond

It’s great to be with you, Talia. Warm greetings, and hope you have a good holiday.

Talia Baroncelli

Same to you, Patrick. Thank you to all of our viewers and listeners for supporting the show and making contributions so that we can continue to make the content that we do. If you’d like to support us, you can do so by going to our website, theAnalysis.news, and also getting onto our newsletter. Thanks for joining us.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | TuneIn | Deezer | RSS

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter

Patrick Bond is Distinguished Professor at the University of Johannesburg Department of Sociology, where he directs the Centre for Social Change.