Protesters have practically shut down Panama for over two weeks now in an effort to keep the Canadian mining company First Quantum Minerals from operating Central America’s largest open-pit copper mine. Michael Fox tells the story and analyses its implications.

Greg Wilpert

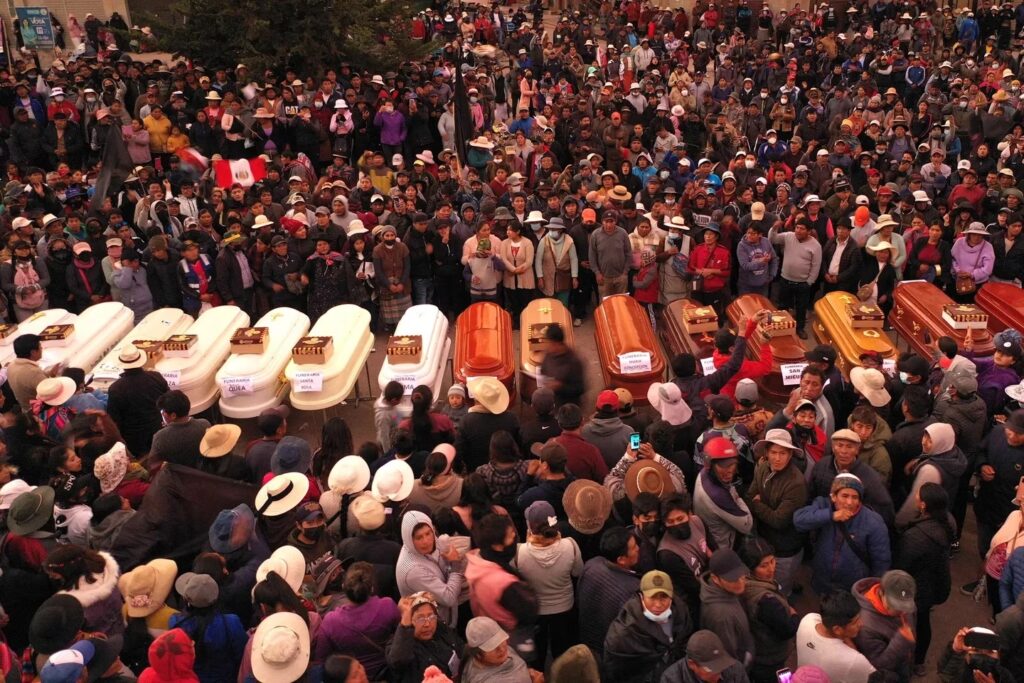

Welcome to The World on Fire. I’m your host, Greg Wilpert. Earlier this week, two anti-mining protesters were shot and killed in Panama, bringing the death toll during anti-mining protests to four. The protests, which have been ongoing for over two weeks now, have pretty much shut the country down. The issue that the protesters are opposing is a mining contract renewal for the Canadian mining company, First Quantum Minerals, which hopes to excavate copper in Panama from an open pit mine.

Joining me to talk about what is happening in Panama and what it means is Michael Fox, who is based in Panama at the moment. He is a freelance journalist and host of the soon-to-be-launched podcast Under the Shadow. Thanks for joining me today, Mike.

Michael Fox

Thanks so much, Greg.

Greg Wilpert

So let’s start with the latest developments. What happened this past week, and what’s the situation like in Panama at the moment?

Michael Fox

The big thing that’s been covering the news, which you just touched on, was this killing of these two anti-mining protesters, where someone, a Panamanian, it went back and forth on whether he was actually an expat from the U.S., but he was not. He is a Panamanian citizen who was born here in Panama. He walked up and shot two people in the protests. It’s a sign of the tension that the extension of these protests, particularly the blockades, is having in Panama.

Right now, I’m in the Western province of Chiriquí. I’m in a town called Boquete, which those who are retired might know of it because it’s a retirement community. A lot of expats are here. We’ve been out of gas for the last two weeks. Products at supermarkets are running short; gas, like heating fluid or heating oil and propane gas in order to cook with your stoves and things like that have been out for several days. There’s no end in sight of when things might be coming back. I was at the store yesterday trying to buy eggs, and you can’t get those. The one positive here is that this is a bread basket for the country. We’ve got lots of vegetables and fruit that elsewhere around the country do not have.

The protests and the blockades have continued. When we talk about the blockades, basically, the Pan-American Highway is the main artery that cuts through Panama, east to west, from the east coast to the west coast. It’s been blocked up and down the Pan-American Highway over the last two weeks at this point. It means that major buses can’t get in, and shipments of goods; that’s why we don’t have gas here as of the last week and a half. In fact, people are now selling gas on the street, but other people are claiming it might be watered down, so don’t use it because it might hurt your car.

It’s a pretty intense situation. Schools are out. They’ve now gone online. University classes have been postponed. Basically, here and in cities across the country are shut down. We’ve been staying at this one local spot by this restaurant and hotel, and they’ve been completely shut for the last few days.

This is really hard, Greg, because it’s the middle of the country’s Independence Day month. Independence celebrations were just last Friday, and they were expected to run throughout the weekend. What that means, this is the biggest tourist moment of the year. This is when restaurants and hotels really make back the money they’ve been losing throughout, and everything has been shut down. It’s been shuttered. There haven’t been any parades. There’s nothing that is happening. For the business community, for commerce, for local communities, it’s been really hard. The fact that there is almost no end in sight is also really concerning. That’s what it looks like now. Protests are still happening. The roadblocks continue, and it’s a hard moment.

Greg Wilpert

Sounds almost like a general strike. How did it come to this? My understanding is that the mining company, First Quantum Minerals, has been operating in Canada for a very long time already. What is it about this latest contract and this copper mine in particular that is causing so much opposition? What are the protesters demanding from the government?

Michael Fox

The most important thing you need to remember here, Greg, is there are several layers of why people are so upset, and we can dive into those in the next few minutes.

The most important thing is this all harkens back to the role of the U.S. government and the Panama Canal. Bear with me for a second. I’ll get to First Quantum in a second. The reason why is because the Panama Canal wasn’t just a canal. It was a whole canal zone that was essentially U.S. property in Panama. It meant that the whole region around the Panama Canal, Panamanians, could not come in. It was not authorized. It was a U.S. enclave within Panama. Panamanians fought for 100 years to get that zone back and to kick the U.S. out. The reason, the thing that every single person in the streets is talking about, is this is a reminder of that. They do not want a foreign company to come in to be authorized and basically cede a piece of Panamanian property, of Panamanian land, to do with whatever they want.

Part of the thing with this contract is the fact that the previous contracts actually said that the Panamanian government or Panamanians could not overfly the area of the mine. Even now, the contract says that the port that is supposed to take out this copper directly from the mine, Panamanians, aren’t authorized to use that without the authorization of the mine, First Quantum. That’s what people are so upset about. This is a handing over of a piece of Panamanian property, and it is a reminder.

It was not so long ago, we’re talking about just 20 years ago, that Panama basically got back that territory that used to be the canal zone. They’re saying, “No, we’re not going to do this again. We are not going to hand this over.” That’s the bigger vision, and that’s really what’s at stake.

I was trying to wrap my brain around it too. Most countries I’ve been in, like Brazil or elsewhere, okay, there’s a mine. People aren’t going to shut down the country for weeks around one mine. Maybe they should, but they’re not going to. But that is what is at stake.

Now, I’ll talk about the environmental stuff in a second. So what happened was going back to the previous contract, and you’re right, since 2019, First Quantum has been extracting copper from this mine. It’s been under operation. It’s been happening for several years. Now backup several years ago, the Supreme Court ruled that the contract with the previous contract with First Quantum over this mine was unconstitutional because it was not to the benefit of the Panamanian good. That first contract, essentially, First Quantum was giving to the Panamanian state something like $35 million a year, which is just chump change, when you think about it, for the major extraction, the size of this mine. Remember, Greg, this is the largest open-pit copper mine in Central America. This thing is huge. It’s a massive amount of territory. In one of my reports talking about it, it’s roughly two times the size of Manhattan. It’s not just a tiny neighborhood or a piece of land. It’s very, very big. That is important. The Supreme Court said, “No, this contract is not working. You need to go back and rewrite the contract.” That’s what the government’s been doing for the last two years.

Now, throughout this entire time, First Quantum has continued to extract coal. It’s continued and has extracted roughly 300,000 tons of copper a year. The government, over the last two years, has been renegotiating the contract. They solidified it. They came to it. They signed an agreement. Then, it came up to Congress on October 20.

Now, Congress can take a long time to debate this thing, but they essentially approved it in three debates over one week. At the exact same time, the very next day, the President signed it into action. That was part of what people were so upset about. Now, the government says that they got a lot of input from the community. People said that is just not the case. They’re extremely upset with the fact that this was approved so fast by Congress. Literally, just in three days, and then they signed in. That also made people say, “Look, they’re willing to just give over a piece of our land for nothing.”

Now, the new contract, what it does, and the government’s been very clear about heralding this as a huge win for the Panamanian state. The new contract basically increases the amount that the state is going to be receiving from this mine per year by 10 times. Now, it’s $375 million a year that the Panamanian state is supposed to be receiving. A good chunk of that money, the President Laurentino Cortizo has already said, should be going to shore up the social security system, which is having a really hard time here. In fact, he came out just days after the protest started and said that by November, by this month, they’re going to be ensuring that pensioners in the country, 120,000 pensioners, are going to be receiving at least $350 a month because of the windfall profits from this mine. That’s, in some cases, as much as 80% higher than what they’re receiving right now. The government’s really looking at this as a profit gainer for government coffers as a way to bring in funds. Of course, it’s really good for the government itself and its image abroad.

Now, of course, it’s also true that the Vice President has long ties with the First Quantum, with the mine itself. A lot of people are saying, “Hey, this is only happening, it’s only being pushed because of the involvement of the Vice President, because of his ties with First Quantum.” There’s been a lot of rumors that First Quantum paid money to the congressional representatives. We don’t have any facts or information about that, but those are rumors that a lot of people are talking about and more reason why they’re out in the streets and so frustrated.

Right now, they’ve got the new contract. People say that this one is just like the old one, except the states are getting a little bit more money. There now have been eight different lawsuits brought before the Supreme Court here in Panama, and they’re waiting for the Supreme Court to make a ruling. That’s really where things stand right now.

Laurentino Cortizo, the President, came out after about a week of the protest and said, “Listen, I’m going to call for a referendum in December, and we’ll let the people decide if you want the contract or not.” People said, “No, we don’t want that. We don’t want the mining contract.” Well over the majority of the population, something like 65% of the population, does not want this and would rather protect the environment in those areas. We’ll get to that in a second. That’s where things stand.

Laurentino Cortizo says, “We’re going to do a referendum.” It went back to the Supreme Electoral Court, which said, “We don’t have the means nor the agenda to be able to do a referendum.” Congress then went and approved and said, “If you want to do a referendum, we can do it, and we authorize the Supreme Electoral Court to do it.” In fact, it looked for a second like Congress might be moving to gut, to recede the contract they had just signed. Then they stopped after two different votes and said, “You know what, we’re going to leave it in the hands of the courts.” That’s where everything is right now.

Now it’s unclear, as you know, Supreme Courts can move slowly. It’s unclear how long it’s going to take them. Many people are saying that it is looking like we might get word from the Supreme Court by late next week, sometime in mid-November. But in the meantime, things are shut down. Like I said, gas is out, propane is running out, food is running short, and tensions are running really high. This is interesting, Greg.

In the very beginning, when the protests launched and hit the streets, this was a wide swath of the population. I’m talking about activists. The major construction union, SUNTRACS, was really involved, and they’re extremely radical. They’ve been out in the streets from day one. You also have students, teachers, indigenous groups, including upper-class folks saying, “We don’t want this. We don’t like the President.” They were banging their pots and pans, which is often time seen as an act of protest from the upper classes—even white business people. Everybody was in the streets. That’s extremely interesting, Greg.

One of the things that nobody has been talking about is why this has not been covered at a deeper level. Obviously, this is touching interests that have to do with Canada, a Canadian corporation, with U.S. financing. Now, if this was something or a situation that the U.S. government didn’t like, I’m sure that we would have heard much more about how these protesters have been in the streets because this has been shutting down the country. Yet outside of Panama, you really have heard very, very little. But it is a massive thing. The big issue is that we don’t know what the end game is or what’s on the horizon and how this is going to end up.

Greg Wilpert

You said you were going to say something about the environmental impact. Open-pit mines, of course, are pretty notorious for being extremely damaging. Just how bad is it in this case?

Michael Fox

Well, notorious for being damaging, absolutely. Remember that this is a high, biodiverse region. The Caribbean coast here is running up and down and is extremely important. According to the contract, what we understand is that as much as a billion cubic meters of water can be used by the company for this mine a year. Remember, this is times of drought.

We just saw a few months ago, where literally the Panama Canal, the water was so low that there was a ship that ran aground and people couldn’t get through it. Now, it has been raining in recent months, and that’s been a godsend for many Panamanians. But remember that at least a quarter of the country does not have running water 24 hours a day, potable running water. People see the ability of this mine to be able to use as much water as it wants, essentially, whereas Panamanians don’t have that same access. People are obviously up in arms. There have been images of tapirs, animals, and the mine plays that who are extremely bad off. The images of the mine are just massive. It’s an open pit mine. It’s what you imagine. The environment is an important thing for many Panamanians.

It’s a fascinating thing, Greg, because the major, maybe the top three issues why people are in the streets have to do with sovereignty and the role of a foreign government. It has to do with the environment. It has to do with the Panamanian Canal, which is a huge source of income for the country. When you think about the fact that people are protesting about these things and willing to stand up in defense of the environment and in defense of their sovereignty is really huge. I think it says a lot about this moment.

Also, Panamanians, they are not going to give up. This is not the type of protest where you say, “Okay, fine, we’ll make some agreements, and then we’ll go home.” That doesn’t happen here. Even more importantly, it’s important to remember just last year, Panama saw three weeks of massive protests that shut down the country roughly from July until August. Those were regarding inflation and high gas prices. It took the government a long time and created a dialog with social movements to be able to sit down and say, “Okay, listen, we’re going to try and resolve this.” Many Panamanians feel that that situation did not actually improve. Things did not improve that much. They’re also weary of entering into dialog with the government about this, the same government, Laurentino Cortizo, that everybody is so upset with. Remember that this isn’t just a one-off, but this comes after these massive protests that people saw last year.

This is the other issue that many business people are talking about, hotel and restaurant owners, is the fact that Panama hasn’t really had its moment after the end of COVID. It’s been in the thick of it for four years. First, you had COVID in 2019-2022. As soon as things started to come back last year, you had three weeks of protests that shut down the country. Now you have three weeks of protests or two and a half, but it’s obviously going to be at least three weeks by the time this is over. Again, this is really hitting the business sector really hard.

Greg Wilpert

What can you say about the government? Laurentino Cortizo, it sounds like he’s being a bit inept in handling this. Apparently, his party is considered to be center-left, but he’s not really known to be part of the so-called Second Pink Tide in Latin America. What’s on his agenda, and who’s behind him?

Michael Fox

Yeah, well, these are great questions, Greg. First off, he’s the former head of the National Assembly and former Ag[riculture] Minister. As you said, his party is center-left but much more centrist. As we’ve seen out in the streets, indigenous folks, unions, workers, social movements, as well as the upper class, everybody’s against him. He really doesn’t have much support at this time. He also has cancer. Many people are pointing to that as a possibility of why he’s unable to handle this situation at the moment, and things have gotten out of hand.

Now, keep in mind also, Greg, that the elections are only six months away. May 5, 2024, are the elections here. It is an interesting moment because with all these protests happening already, what we saw from the protests last year is that some members, more radical, progressive members of the left, really have risen to the fore of this network of roughly 10 people that are going to be the 10 top candidates for the elections next year. Obviously, Laurentino Cortizo is not on the ballot. It’s going to be really interesting to see what an impact these protests could have.

If you look at what’s happened in many other countries that have seen turmoil and protests in the lead-up to elections that are happening, you either have the possibility of someone much more on the left, much more radical, coming into power, or you have the possibility of something like [Jair] Bolsonaro happening, somebody much more on the right. That’s my prediction for next year. We don’t know what’s going to happen, but people are upset with the traditional parties right now. They blame them for passing this through Congress. They blame Laurentino Cortizo for signing it immediately. They say this whole system is messed up and screwed up, and we need a massive change. I think that in next year’s elections, we’re going to see a shake-up. The big question is, is this going to be a shake-up more in the direction of [Nayib] Bukele in El Salvador? Are we going to see a shake-up more in the direction of Lula [da Silva], say, in Brazil?

Greg Wilpert

Now, finally, you have a podcast that’s coming up called Under the Shadow. What shadow are you referring to here? Is this shadow present in Panama at the moment? And if so, how?

Greg Wilpert

The shadow is present everywhere across Latin America and has always been. The shadow is the United States. In fact, the political and economic movements and tools of the United States. It’s also the Monroe Doctrine. Remember the Monroe Doctrine? We go back, James Monroe, basically, exactly 200 years ago this year said that the United States had a right to intervene across the region, that the foreign powers, the European foreign powers, could not no longer intervene in Latin America. It was the United States that was essentially going to. This was the United States realm. Latin America was the United States’ backyard. This shadow is U.S. and U.S. policies, whether that’s coups and foreign policy abroad or the innumerable invasions that have happened to almost every country in the region. This is obviously the shadow here.

Now, what’s interesting about the shadow is the fact that in Panama, remember, the shadow is obvious. Literally, the United States helped to break Panama away from Colombia and then took over the Panama Canal region for 100 years. You cannot talk about what’s happening, even though many news outlets do, but you cannot talk about what’s happening in Panama right now, as I mentioned at the beginning, without talking about the 100-year-long occupation by the United States of the Canal zone and what that enclave meant to Panamanians across the country because having that enclave of a foreign country inside their own country has made them absolutely resentful of the possibility of this happening again. That’s on the minutia of what we’re seeing, but it’s extremely important. That’s what everybody is feeling when they’re marching out in the streets of the possibility of having a foreign company or a foreign country come back here and do the same thing.

Also, don’t forget, Greg, and this is really important. First Quantum Minerals, it’s a Canadian company with Chinese and Korean backing, but also U.S. investment companies, including, I’m looking down at my notes right here, U.S. capital groups, Fidelity, Vanguard, and BlackRock. All these people have investments in First Quantum. Stocks have dropped. They’ve tanked just over the last month by 50%– First Quantum stocks. The mine itself is largely invested by First Quantum. But then you have other investors, and we don’t actually even know who the other investors are in the mine. We know who the investors are in First Quantum, but we don’t know necessarily who these other investors are involved in the mine. All these things are extremely important. They’re all foreign investors. This is why those people are in the streets.

If you’re listening right now, you can actually hear some horns because it’s another protest that’s starting this afternoon. This is deeply, and it’s profound for people across Panama. Obviously, the shadow looms large everywhere, everywhere across the region.

Greg Wilpert

Well, just one more follow-up on that. The United States government, of course, I imagine, is watching the situation very carefully, precisely because Panama is the location of the Panama Canal. Apparently, this is having, or it’s very possible that it will have, a spill-over effect that is the protest movement, perhaps for the elections and what that could maybe mean for the Panama Canal in the future. Has there been any reaction from the U.S. government? Have you seen any movement or any efforts to interfere or influence the situation?

Michael Fox

We haven’t seen much from the U.S. government. They have been obviously sending messages to foreigners in Panama, which is usual, telling people to be wary about protests and things like that. Stay away from the protests. Stay at home if you can. We haven’t seen a major push by the U.S. government in this situation. I think they’re trying to stay out of it.

But absolutely, how this is resolved in the next few months and what happens for the elections next year is going to be extremely important for the future of Panama and the future of the canal. As far as I understand, shipments are still happening. I’ve been in touch with people and companies that are shipping outside of Panama and shipping elsewhere. What it’s meant is that at least those in Panama City have had to bring shipments or be bringing cars and elsewhere to Colón and elsewhere overnight so that they’re not involved in the major issues with the big blockades, getting those from Panama City to Colón. As far as I understand, there hasn’t been a major interruption with the canal itself. But obviously, these are major concerns because this is Panama, and it’s a massive hub for transportation internationally and what that could mean.

Greg Wilpert

Okay, well, we’ll leave it there. I’m speaking to Michael Fox, a freelance journalist currently based in Panama. Check out his upcoming podcast, Under the Shadow. Thanks again, Mike, for having joined me today.

Michael Fox

Thanks so much, Greg. Appreciate it.

Greg Wilpert

And thank you for joining The World on Fire. Until next time.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | TuneIn | Deezer | RSS

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter

Michael Fox is a freelance reporter and video journalist based in Brazil. He is the former editor of the NACLA Report on the Americas and the author of two books on Latin America.