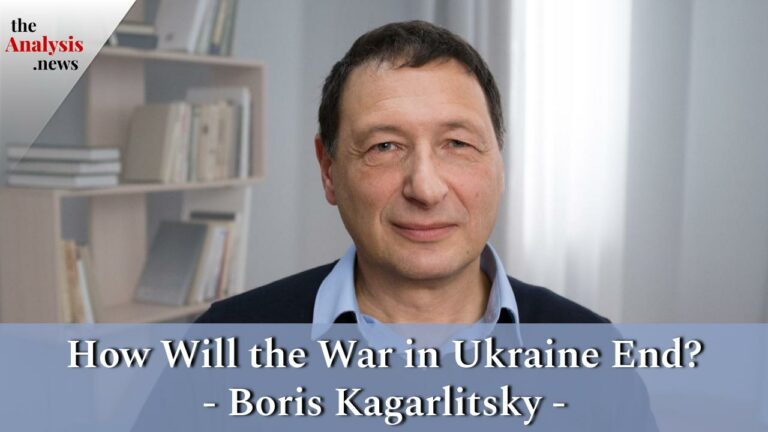

Éric Pineault, professor of ecological economics at the Institute of Environmental Sciences at the University of Quebec in Montreal, explains how the fires raging in Canada are a corollary of the paradigm termed Extreme Oil. He discusses various oil and gas projects across North America, as well as the Canadian government’s support for the Trans Mountain Pipeline project, and how terms such as “net zero” and “carbon neutral” are misleading and conveniently serve Big Oil’s aims.

His recent book A Social Ecology of Capital presents an empirical analysis of capitalist societies, which both builds on and enhances Marxist theories by accounting for the energy extraction and colonization of ecosystems, a characteristic of what he terms our “fossil-industrial” society. His conception of capitalist metabolism outlines extractivism, production, consumption, and waste dissipation, which leads to an absorption of surplus energy, capital accumulation, and profit maximization. Most importantly, how is this understanding of social ecology useful for furthering a project of emancipation?

Talia Baroncelli

Hi, I’m Talia Baroncelli, and you’re watching theAnalysis.news. I’ll shortly be joined by Professor Éric Pineault to speak about wildfires in Canada, big oil and gas in North America, and perspectives on the Social Ecology of Capital. If you enjoy this content, please go to our website, theAnalysis.news, and donate to the show by clicking on the red button at the top right corner of the screen. Most importantly, please get on our mailing list. That way, you’re notified every time there’s a new episode. Go to our YouTube channel, theAnalysis-news. Like the channel, subscribe and hit the bell. See you in a bit with Éric Pineault for a very interesting discussion on social capital.

Joining me now is Professor Éric Pineault. He’s a professor of political economy at the Environmental Sciences Institute at the University of Quebec in Montreal. He’s also a contributor at the Corporate Mapping Project and has recently published a book called A Social Ecology of Capital. Thank you so much for joining me, Professor Pineault.

Éric Pineault

Thank you.

Talia Baroncelli

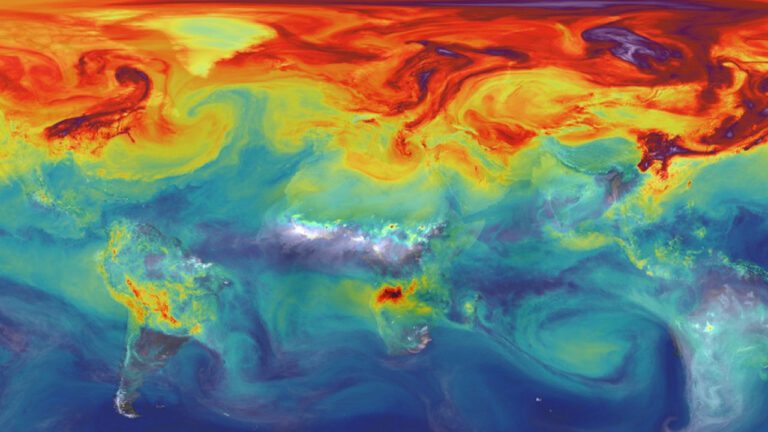

Well, it’s great to have you because I’d like to speak to you about your book today, as well as what’s going on in Canada and the United States. There have been horrible forest fires, horrible wildfires, which have destroyed over five million hectares of land across Canada. At the moment, the air quality has been so terrible. I’m sure you’ve been affected by it where you are in Quebec. I was wondering if you could situate these forest fires within the context of a concept you speak about called extreme oil. We can view these forest fires as an isolated catastrophe, but I think your work really is able to show how they’re tied to other processes.

Éric Pineault

Yeah, sure. Well, I think we have to acknowledge that these forest fires are created by climate change. I think that the boreal forest does have a fire cycle, usually to run 100 years. Every century, a patch of forest will burn. But these fires are usually not as deadly and not as widespread. I think this is a cycle that is entropic in nature.

Once we’ve connected that dot, we say the forest fires are connected to climate change and to the way that we’re transforming the climate, then we have to say, well, what is climate change caused by? I think that is a question that we now know the answers. It’s caused by an economy and a mode of living that is tied to fossil fuels. There are other factors that contribute: land use, change, and the pervasive use of cement and concrete in our urban metabolism. Maybe we can come back to that later. I think the prime suspect here, the prime driver is hydrocarbons, be it coal, gas, or oil.

Extreme gas and oil is an expression that was invented by movements in the U.S. and in Canada. We’re on the ground, challenging fracking pipelines and mountaintop removal, and in the case of coal, saying that these new waves of extractive activity in North America were in a dual context.

On the one hand, it was impacting marginalized communities mostly, and it was impacting landscapes and ecosystems that hadn’t been impacted yet. It felt like all of a sudden, there was this huge grab of resources and spewing out of activity that was transforming the land and destroying the ecosystem. That was one part of it. It was extreme in the sense that it was not something that we had experienced in the past.

Then the second aspect was the fact that you’re burning or you’re extracting hydrocarbons that you can’t burn; that’s basically why it’s extreme. We know this. The science is very clear. There’s no way around the science that says this is just unburnable carbon. It’s way past the budget. We know that we have to burn some carbon to do this transition away from carbon. The amount that’s being extracted, the level of extraction, and also the reserves that are being discovered. We know they’re there, but the reserves that are being capitalized, let’s use more specific vocabulary, by these practices. These reserves that are being capitalized are unextractable. There are other factors.

Extreme oil is also about how you have to burn a lot of oil to get the oil, a lot more than in the past. When we started using oil, we would have to burn about one barrel to extract about 200. You basically put a pipe in the soil, and it would just start to gush out. Today, at best, we’re like 50 to 40 to 1. In the worst case scenarios, when we’re fracking and when we’re transforming sand into oil, which is what we do now with tar sands, then it’s horrible. You’re like at 5 to 1, 6 to 1, or sometimes 10 to 1, so you have to burn one barrel to get 10. You’re burning a lot of oil to get oil. You’re burning a lot of gas to get gas. Sometimes you’re burning gas to get oil if you’re fracking.

When you frack for oil, let’s say in North Dakota, then you put your pipe in, you frack, and then you’re not sure about the mix you’re going to get. You’re going to get some oil. You’re going to get some gas. You’re going to get some stuff in between. So what do you do? You want the oil, you don’t want the gas, so you flare it. The opposite happens in BC. You’re fracking for gas, but then you get these liquids that are coming out. What do you do? Is there a pipe or a truck that can haul it away, and somebody wants to buy it, or do you end up flaring it because there is no economic use for it?

These new hydrocarbons are much more carbon intensive, and that’s why they’re extreme. It’s not only that we can’t burn the carbon, it’s not only that the way we extract it is destroying ecosystems and impacting communities in novel ways, but it’s also that it’s so much more costly for the environment and for the climate to extract this carbon. So that’s why it’s extreme.

Talia Baroncelli

Looking at these industries, big oil and big gas, or even looking at the tar sands in Canada, for example, would you say that private investors are still heavily investing actively in these sectors? Is this more consolidated rather than a booming sector?

Éric Pineault

Well, for Canada, it depends on what you’re looking at. If we are looking at the oil sector, it’s consolidating. In our research at Corporate Mapping that I did back with Ian Hussey and others about 5-6 years ago, we saw a sector consolidated after the bust in 2014 when oil prices started to dip. It’s a sector. When you consolidate, well, then usually what happens is governments step in and help out. That’ll bring us to discuss other things.

We see this consolidation on the East Coast. If we look at Newfoundland, which had jumped into this oil boom through offshore oil projects, which transformed Newfoundland’s economy after 2008-2009, the numbers are astounding. You have more than 50% of the private sector invested in Newfoundland, which is just one industry, oil. It’s a massive dependence on one sector. Also, in timing, it’s really weird because… well, not weird, but it’s very dramatic. The cod fish recollapses, and then, at the same time, the oil boom happens. So the economy basically transitioned to fossil dependence.

Well, now, today, you see Equinor, this major extractor from Norway that suspended its project to extract offshore oil off the coast of Newfoundland, basically setting extraction costs. The oil is just too expensive, but prices are not there. So it’s a sector that’s consolidating more than it’s booming.

Gas is another story. Prices are low. Prices are desperately low, but still, it’s booming. Fracking is this self-perpetuating industry where money is being gushed into the sector, and you frack for four or five years, then it dries out, and you move 200 yards, 300 yards further, and you go at it again and again and again. That sector is booming.

Canada’s problem with gas is that we have a scale of extraction that is too high for what we can consume domestically. We’re constrained to export. If we would bring down the volume of extraction to what we actually consume, it wouldn’t be financially viable. The industry costs too much. The question of scale, as a scale-up production, unit costs go down; it’s this economic thing. We’ve got an exportation constraint or imperative in Canada. We have to export the gas. Exporting it to the U.S. via pipes is what we did traditionally.

In the U.S., gas is pissing out of all the pipes everywhere. They’ve got too much gas, too, because they’re fracking it also. The only economically or capitalistically viable way out of this conundrum is to export it as LNG somewhere. That’s why we’ve got this pressure to accept all these LNG projects because it’s the only way that this industry can survive. That industry is growing. It’s not consolidating.

Talia Baroncelli

Is that why the Canadian government has essentially said that they would guarantee loans for the transnational pipeline project, something like three billion Canadian dollars?

Éric Pineault

Yeah. Canada’s got this export constraint problem that we have to export it. I think we have to widen our lens a bit. I would say North America has surplus hydrocarbons. We have too much of it, so we have to export it. That’s when the Canadian government comes in as an important economic supporter of the hydrocarbon industry.

In the case of oil, what the government does is it has supported the consolidation process by buying up a pipeline that the private sector couldn’t economically build. It just wasn’t viable to build it anymore. So the government stepped in, bought it, and it is spending billions and billions. Costs are always going up trying to finish this pipeline. The purpose of this pipeline is to bring shipping costs down for the oil that is coming out of Alberta. So that’s going to help the consolidation process by bringing export costs down. So that’s on that front.

On the gas front, it’s a different story. Since the industry is expanding, we know that the economics of extraction is that often, the extraction of a resource is limited by the capacity to export it and put it on world markets. You might be sitting on billions, but if you can’t send it anywhere, then it’s just not worth anything. We have to build up our export capacity. Gas, the only way to export it on the world market is as LNG because we don’t have pipes that are going from Vancouver to China, so you have to put it on a boat and then send it out on the world markets and hope somebody buys it up. That is one of the ways that the Canadian government is supporting the expansion of the industry.

The other way it’s supporting it, which is much more twisted, I would say, is through hydrogen. The government is a big fan of this hydrogen economy, which is a really weird concept because hydrogen is not a source of energy. Hydrogen is like a battery. It’s a really inefficient battery. At best, depending on what you’re converting into hydrogen, the losses go from 30% to 90% of the energy that is lost. But anyways, hydrogen, you can make it out of renewable energy; that’s one way to do it.

The easiest way to make hydrogen is you take natural gas, and I’ll do some chemistry for a second here. CH4: an atom of carbon with four atoms of hydrogen. So if you split that up somehow, you get big-time hydrogen. You get the H2 easily. The easiest way to do it is to transform natural gas methane into hydrogen. This hydrogen economy hype that the Canadian government is pushing as some renewable energy solution is a way to support the gas industry.

Talia Baroncelli

It’s essentially greenwashing hydrogen, isn’t it?

Éric Pineault

Yeah, it’s greenwashing. Exactly. Yeah, hydrogen is big.

Talia Baroncelli

Back to greenwashing in general, the Canadian government obviously has all the scientific reports in front of them. They’ve seen how global warming is not going away and how these increases in global temperature will eventually lead to tipping points, which will then ensure that global warming will not be reversible in any way, shape, or form.

Maybe this is a naive question, but why is it that the Canadian government is supporting these projects and characterizing the Trans Mountain Pipeline as part of its long-term economic strategy when it knows that in a few years, in a few decades, this is not going to be sustainable? The profits they get from these projects will be meaningless if people can’t even live in the country anymore.

Éric Pineault

Well, a state is a complicated thing. It’s not a unified entity. We often say that the state is a space of conflict. I think that the current Canadian government is an example of that. On the one hand, they do have climate policies in place, and they do seem to want to be going toward their Paris Agreement engagements. On the other hand, the oil sector has prominent support from the Canadian government.

The oil sector is oil and gas; I’d say more oil and gas, not coal. Coal is very marginal in Canada. Oil and gas is a structuring element of the Canadian capitalist economy. It’s not only about Calgary and Edmonton. It’s also about Toronto and Bay Street. The Canadian banks are tied into the oil and gas sector. Our financial markets are tied to this sector. It’s a cluster of interests that is very important. We haven’t been able to marginalize this cluster of interests as others.

Let’s zero in on Quebec. In Quebec, because of the absence of a structured hydrocarbon sector, we’ve been able to marginalize and pass a law saying there will be no extraction of hydrocarbons on Quebec’s territory. That’s the [inaudible 00:16:34] law that was passed last year. That is not something that could be possible in Canada, given the economic structure and given the class interests that are embedded in our state and our economy. I think it’s just a question of class here.

You’ve got this financial class that is really dependent on assets that are locked into the hydrocarbon sector and these fossil assets. Again, we have to differentiate between gas and oil. It’s not the same dynamic. In the case of oil, we’re sitting on maybe 30 years of income. If you look at this life cycle of the different projects that exist, either the ones that scrape the sand and transform it or the ones that use these more complicated processes where we’re injecting steam and then we’re pumping out the tar in a more liquid form. These two basic ways of extracting the infrastructures and assets that are in place today have a life cycle that will last about 30 years. So the Canadian government basically wants to guarantee that that income will be there.

Their economic argument, I don’t agree with it, but I can understand it as an economist. The economic argument is basically, well, yeah, the world will need oil for the next 30 years. Of course, it will. So why not Canadian oil? Why should it be Russians or the Venezuelans or the Qatari or whatever? Why not Canadian oil? So we’re going to be in the race. We’ll be the ones that will extract, refine, and then sell the last drop of oil humanity will consume. That’s really the way they think.

Gas is another story. Gas is still being touted as a bridge fuel. It’s this thing that we’re going to need all through the next century. As we’re consolidating our oil sector, we’re expanding our gas sector. There, the logic is really to company this expansion. On the one hand, part of the government and the state say, well, this is going to be horrible. Climate change will imply adaptation. We have to work hard to meet our targets. On the other hand, well, we’ll find solutions in the future. We can keep on pumping oil and fracking for gas.

Then there’s always been this unicorn or flying toaster, depending on your imagery, solutions that have been around for the last 20 years. Carbon capture and storage are the most important, which is really, I was going to say, stupid. I might as well say stupid solution because it brings down the CO2 intensity of what we extract. When you burn it, it’s still a barrel of oil you’re going to burn. The reasoning of the Canadian government is if we can bring down the CO2 or the GHG, the greenhouse gas intensity of our oil to the level that it is average worldwide. It won’t be dirty oil anymore. It’ll be normal oil. That’s their idea. So we’re going to pump all this public money supporting these projects that are really dubious, to be able to have normal oil. That’s the strategy that is big. It’s not a net zero strategy. It’s not a climate-neutral strategy at all. It’s just, let’s normalize our oil.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, sorry to interrupt you, but I remember a few years ago when the Canadian government was quite upset at the Europeans when the E.U. characterized or categorized the Canadian oil as essentially dirty because it’s from the tar sands. They didn’t like to be called that. They didn’t like their oil to be considered dirty. There’s this campaign to greenwash it and present it in a different way.

Éric Pineault

Well, that campaign bore fruit in the sense that we hardly use tar sands anymore. We tend to sell oil sands, which is an invention of the industry because it is actually tar. It’s not oil in the sand. You get oil at the end of the process, but what you’re looking at is tar. If you’ve ever seen this stuff, it looks like pitch. The stuff you use to repair a driveway or that you put on your roof to tile it. It really looks like pitch.

Talia Baroncelli

Why don’t we speak about the language? I think the language that’s used is very important, especially when looking at environmental activists, for example. I know a lot of your work has illustrated how there’s this symbolic side of the capitalist structure. There’s the discourse and the symbolism that is essentially characterized by capitalist relations and activists feeling like they have to be viewed as legitimate actors, and using the word oil sands as opposed to tar sands is maybe an example of how these power relations affect activist circles. I don’t know if you still see this trend among environmental activists, or has there been a shift there?

Éric Pineault

Well, yes and no. I think hardly anybody uses tar sands anymore. I think that’s because people use oil sands, but I think oil sands have been dirtied anyway. The industry didn’t manage to pull it off. They managed to pull off the idea of, okay, let’s talk about oil sands, not tar sands anymore. On the other hand, oil sands are seen negatively.

Now, I would say the new vocabulary that is emerging in business circles or even by the Trudeau government is a lot about net zero, carbon neutral. These expressions are very ambiguous. On the one hand, net zero, well, it’s the idea of an addition. You can subtract what you added in, then the technologies of subtraction are presented as existing, as to scale, and as efficient. They are not. They exist as prototypes. The ones that are working today are very inefficient. We were promised 90% capture, and we’re at 60%, at best, in tar sands for this carbon capture and storage. Most of the stuff is being used to pump more oil out anyways. It’s not carbon capture and storage; it’s carbon capture, use, and storage. We’re actually using the CO2 as a way to frack or to push oil out.

Net zero can be a trap because then you’re brought into a conversation where, oh, we can continue extracting as long as we compensate. That’s one of the, I’d say, the new ways in which we’re being caught up in these debates.

Another emerging, I would say, linguistic frontier or linguistic struggle or narrative struggle is around growth. If you look at the way the Canadian government continuously presents its different climate policies, it’s always this idea of net zero or carbon neutrality or decarbonization. They always add the expression clean growth mechanism or growth for the middle class or growth that gives prosperity to the middle class. These words are always there. These are keywords: growth, prosperity, and middle class. There you see this ideological construct which is very strong and ties together the middle class, prosperity, and economic growth.

This is becoming interesting because the climate science that is being presented in, let’s say, the last IPCC report, the Sixth Assessment by the IPCC, is starting to debate growth. Voices are being more and more heard from natural scientists and from some heterodox economists saying that growth is just not something that is possible if you want to attain our goals, both for climate and for biodiversity. I think this is going to be a new train of struggle where the word growth itself is going to be politicized.

Talia Baroncelli

Right. I think you also speak about degrowth as a concept and also as a movement to show that in order to live on this planet, if you’re pushing these planetary boundaries or these limits of ecology, then the economy isn’t sustainable. Growth for growth’s sake isn’t, as we’ve seen over the past few decades, really not something that we should be pursuing.

Sorry, maybe that’s a good segue into your book. The book that you’ve just published, The Social Ecology of Capital, is really a fantastic read. One thing you do, well, you do many things in the book, but one thing you do is you speak about capitalist metabolism, essentially. So you speak about two different forms of societies, namely, which fall under this capitalist metabolic structure, which would be agrarian societies and then fossil fuel industrialized societies, which is the current moment we’re living in right now. Maybe you can explain that concept of metabolism because if people are familiar with [Karl] Marx, he does speak about metabolism in terms of labor and means of production with regards to labor. I think the way you use it is slightly different. So maybe we can speak about that.

I’ll actually just read one part of your book because I think it’s really fascinating. In your introduction, you speak about how the materiality of capitalist metabolism appears in one of three guises:

“Social metabolism as flows of energy and materials passing through societies or throughput, social metabolism as an accumulation of material stocks, and social metabolism as a colonization of ecosystems by human activity.”

I think that sums up essentially what social metabolism is. Please elaborate on it because it’s a very fascinating concept.

Éric Pineault

Yeah, sure. It’s a concept that is used by Marx in Capital. We can get back to that in a few seconds. It’s a concept that reemerged in the ’90s. It emerged in debates and discussions among ecological economists that were trying to move away from an understanding and representation of the economy uniquely through monetary flows. They wanted to have a representation or monetized assets. They wanted to have a representation of the materiality of the economy.

There was a really important paper published by colleagues in Vienna, and my debt to them is really huge, and I talked about it in the book. Marina Fischer-Kowalski and Helmut Haberl published this paper in the ’90s called Tons, Joules, and Money, saying we can look at the economy through the lens of money, and that gives us GDP, but we could also look at the tons of matter that are going through, or we could look at the joules, which are energy units that we need to expand to. That’s really where the concept of metabolism was recast as a way to look at the material frame or the material structure of the economy and to have a language that could represent that materiality in and of itself, to move away from the necessity to always translate into monetary terms this material basis.

Metabolism is a concept that is pretty easy to understand. It’s the idea that a society, like a living entity, must extract, absorb, transform, and reject elements from its environment. In doing so, this is an entropic process where we take in energy, we take in complex matter, and we reject more simple degraded forms. They can be useful in an ecological cycle. What one rejects is another’s food, often in these entropic cycles.

This idea of metabolism was then brought up to analyze societies, basically saying, well, a society does this. A society must harvest or extract, and it then transforms. It’s a way of looking at the economy. What it does, and I think that’s where it’s powerful, is that the power of metabolism is to move us away from a dematerialized representation of the economy, which is really the one that was dominant throughout the whole cycle of political economy, bringing down the economy to two basic relations: production and consumption.

What social metabolism does is say, actually, no, an economy rests on four structures or four relations, which are extraction. To produce, you have to extract in a material world. If you’re in a nonmaterial world that could exist in our imaginations, we wouldn’t have to extract anything. In the real world, we have to extract to produce. So extraction, production, consumption, and then when we consume, eventually, something that is used will be used up. Then it will be dissipated or wasted. We talk about dissipation as a technical term. The notion of using up is important because it’s a social notion. It’s not a biophysical notion. The decision that something is used up often has nothing to do with its physical use. It has more to do with the social decision that it’s not useful anymore for a bunch of reasons, which can be cultural, which can be economic, which can be capitalistic in nature.

We have this four-tier economy, and that’s the metabolic structure of an economy. Then you can say, well, okay, what’s the backbone on which a society thrives? Social ecologists and environmental historians have divided societies through different metabolic regimes. The two that are relevant for our discussion that you highlighted are the agrarian and the industrial fossil.

In the book, I do spend a lot of time delving into the implications of these two regimes. What is an agrarian regime? Well, it’s where the backbone of the material existence for societies through agriculture. What is agriculture? It’s putting plants to work. It’s basically transforming through the colonization of an ecosystem, transforming it and maximizing its capacity to capture solar energy and store it in a form that is useful or that is desired. It’s not all from the question of use; it can be from the question of desire, of social desire, that is desired and useful or necessary to power relations in a given society.

Necessary to power relations because– and this is James Scott’s argument in Against the Grain. In certain societies, we could say that the decision to move towards grain instead of staying in other forms of agricultural relations was tied to power structures that were being built up, hierarchies around urban environments. The agrarian regime, its specificity is that it’s through ecological relations that human societies thrive and reproduce themselves. Ecological productivity, the capacity to transform solar energy through photosynthesis into forms, into biomass, basically, is the limit, is the ceiling in which our societies will develop and thrive. What we call technically net primary production, which is the capacity of plants to take solar energy and make biomass, is basically what will limit the development of a society. It’s inside those limits that societies will thrive. This has a bunch of implications that have been studied by a bunch of historians and political economists.

Andreas Malm explored this, including others. Jason Moore has explored this. How do you temporally overcome that barrier? Well, you can do it by setting up slave-based plantations. That’s one way to go around the problem. Another way is to pillage new environments, or pillage societies, or set up tributary relations. It’s always inside this ecological productivity.

Fossil societies are radically different. Whereas in an agrarian society, you must produce the surplus that you will then live off. An industrial fossil society finds the surplus under its feet. The energy is stored in coal and oil, and gas that is there. That society’s mode of production and extraction is how can you absorb this massive surplus of energy and put it to work and, in doing so, accumulate capital and make a profit. It also leads to a new representation of the surplus, which isn’t the same as in agrarian societies. In agrarian societies, the surplus appears as grain. It appears as the muscle power that can be harnessed and harvested or coerced into work. This muscle power can be human, or it can be animal. There are a lot of animals that work in agrarian societies. It’s something we have forgotten. Half the biomass that we produce in agrarian societies goes to feeding animals that work for us.

In a fossil society, absorbing this surplus goes by new rules. You represent, symbolically, the surplus’s energy as this abstract capacity to work that then puts to work human bodies. It’s very different. This abstract capacity to work and I’m thinking of Cara New Daggett’s work on The Birth of Energy, her beautiful book on The Birth of Energy. This abstract capacity, which is basically what physics thinks about back in the 18th and 19th centuries, means that the source of surplus that you’re extracting can become many things. It can become heat. It can become mechanical work. It can become chemical work. It can become kinetic energy. It’s much more plastic. It’s like abstract labor.

One could say if one would take an expression from [Max] Weber, there’s an elective affinity between fossil fuels and capital because of its plasticity, the fact that it’s plastic. That’s one of the important ideas that I don’t invent. It’s out there and has been discussed by other scholars in the past 20 years, but I try to bring it together in a synthesis that’s original. It also speaks to the way we will, if we remain in a capitalist system, that we can understand the transition. We’re caught up in this idea that out there somewhere, there’s abstract energy that can be harnessed and appropriated through private property relations, and that can be articulated to assets that will generate income in the form of profits. Accumulation. This idea that there’s a stock of energy out there somewhere that is a basis for a new cycle of accumulation. We’re desperately searching for it. We’re trying to find it in hydrogen. We’re trying to find it in the wind. We’re trying to find it in solar energy, but we’re trying to find it with this symbolic and ideological framework and also with the social property relations of capital, which depends on this idea that came out of coal, oil, and gas, but mostly coal.

This imaginary that was built out of coal is this idea of it’s out there and can be put to work in various forms. It’s plastic. It’s appropriable. We can appropriate it. Of course, we have to move people away. Of course, we have to violate and expropriate people to get to it. It can somehow be captured by property relations. That’s the framework in which we’re looking at transition today because it’s a capitalist transition.

That’s one of the things the book tries to do. It tries to share this language of social metabolism, and it tries to bring together this language of social metabolism with how we can understand a capitalist economy, an advanced capitalist economy based on large corporations that overproduce and depend on the overconsumption of what is overproduced. That is basically what the book tries to do.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, it does a really good job of doing so. I think another aspect that it speaks about is how it relies so much on monopoly capitalism and the consolidation of monopolistic industries. We see that in the oil and gas sector, but can you maybe speak about other sectors?

Éric Pineault

Yeah, that’s where it came from. I’ve been discussing the book a bit in various circles. In certain Marxist circles, people are like, oh, that’s such an old theory, monopoly capital. It’s like back in the ’60s. Why are you using that? There are much sexier theories today about cognitive capital and about the tendency of the rate to fall. Globalization implies a lot of competition. Yeah, you’re right. I do acknowledge that there are other ways of looking at capital, but when you’re working in the extractive sector, when you’re looking at extractive industries, it’s a monopolistic sector. There’s no way around explaining it. You can’t use other theories to explain what’s going on. It’s really a monopolistic sector.

Talia Baroncelli

Yeah, it would also potentially explain inflation and explain why prices are so high in certain sectors.

Éric Pineault

It does. When you’re working in the real world of prices and of materials and not in the, I would say, more abstract world of value and these more sophisticated theories of value. I tend to work in the real empirical world.

If you look at Glencore, for example, Glencore extracts around 9% of the world’s copper, but it ships, transports, and sells 18% of the world’s copper—all the metals. Take any metal that you want, except lithium. Lithium is an emerging material; it’s not consolidated yet, but even that is changing quickly. All the other metals, nickel, iron, aluminum, bauxite, whatever, you’ve got four or five big, huge global corporations that control the market. It’s the same thing with wood or cement. You’ve got three big players that control the world’s production of cement, and the rest is marginal.

China does mess up the picture because China has these state-led corporations that are huge. So you put them in. You’ve got one in China, so you end up with four monopolies. Then if you look at the waste sector, it is the same thing. In the waste sector, you’ve got four or five major corporations that control waste flows globally. So if you look at the materiality of our economy, you’re looking at a small number of huge corporations that have worldwide reach and that have sunk their capital into assets that are tied to the extraction and waste of these materials that make our world. Be it oil, be it cement, be it wood, be it whatever. For oil, I’m not thinking palm oil, soybeans, or corn.

When you study these material flows, you feel like who’s going to develop the next app that’s going to revolutionize the way we use our phones? Then you have competition. You’ve got these venture capitalists, and you’ve got this very dynamic system of heightened competition. When you look at the world of the materials out of which our phones are made, you’ve got four or five big players. That’s it.

Talia Baroncelli

Also, historically, if you look at this transition which you speak about between moving from an agrarian society to a fossil fuel industrialized society, you speak about two different things. One is using coal to essentially get more coal as being a characterizing or decisive feature, but also the proliferation of means of transport and being able to ship different goods, grain, sand, or whatever it might be in order to industrialize. I’m pretty sure that even then, there were maybe only a few companies involved. I think this idea of monopoly capitalism and monopolies forming in specific sectors has always been historically relevant, at least in the past few centuries.

Éric Pineault

Well, yeah. Well, there are two phases to this, which are interesting. The first phase, I didn’t really work on it in the book, and I’d say that Jason Moore is the appropriate person to discuss that. The first phase would be inside the huge commercial empires that we saw when the colonial system was being put in place by European capitalist powers, where you had these colonial companies. Canada is basically the fruit of that effort and that process. So you have these colonial monopolies that are set up, and they control the circulation of what you can extract in an agrarian setting through either growing it or pillaging it. It’s the two basic means. You either force people to grow it, and then you can grow it through settler colonialism, which is what happened in Canada, or you can grow it through a slave base system, which is what they did in the Caribbean and the southern U.S. The commercial interest that is putting into circulation this matter, which is essential to capitalism back then: wood, fibre, cotton, and sugar; these are monopolists.

There’s a second wave of monopolization. That’s the one that I work with more, which is tied to the corporate form. Corporation, as we know it today, emerges at the end of the 19th century. There are two basic areas which are strategic to the emergence of the modern corporation. Railroads. You go from a mess of thousands of small railroad companies that are competing against one another to a consolidation process of a small number. The corporate form and corporate law now emerge out of this context. Then you have the same legal, political, and economic process continued in the steel industry, which is tied to the coal and oil sector.

Corporate laws that exist today are tied to standard oil and break up standard oil into smaller, less continental entities. Standard oil is basically, I would say, brings the process of the creation of the corporate form to its most advanced stage. It matures the process that emerges out of the railroad sector.

The transition towards a fossil industrial economy, at least if we take North America as an example, is intimately tied to the institutional transformations that bring about the modern corporation. The two are tied together. I don’t think I make that point enough in the book. Actually, I realized that it’s a story that I tell when I teach courses, and I should maybe eventually write it up better. But that’s really an important aspect.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, we could probably do a whole episode just on that historical aspect. I know you have to go. One last very short question, which I think is important. How do you see your concept or this concept of the Social Ecology of Capital contributing to an emancipatory project of redistribution of wealth, of trying to undermine or dismantle these capitalist relations?

Éric Pineault

Well, I’d say two things to answer that question. The first thing is the book tries to propose a language, a new language, or a language that’s out there. I don’t want to invent the words. The words are there. Synthesize. To translate this language, bring it together, and a language useful to our struggles against fossil metabolism, but also for. This language is about materiality, which is a language that is notably absent, I think, in a lot of our critical theories today. I’ll come back to that point in a second.

I think the book, on that issue, doesn’t fail but doesn’t live up to it. The book is very scholarly. It’s short and dense. I am writing a book in French that is more geared toward activists, actually, because my struggles in Quebec are with… I work with francophones, so I’m writing a movement-based version of this book, which eventually could be retranslated into English, I guess. I think this book is not a book that an activist can just grab and read through on a weekend.

Talia Baroncelli

It’s very dense.

Éric Pineault

A friend of mine says it is like cheesecake. But what does it do? That’s the last chapter. I have the book here, actually. The last chapter, the title is Emancipation Amid the Ruins of Fossil Capital. I think that’s important, this idea of ruins. The materiality of our society will not disappear the day after the revolution. I don’t see our current social transformation as being one of a quick revolution in which everything changes at once. I think it’s going to be a more protracted process of long and agonistic change in the context of having to adapt to a world that is going to be more and more hostile because of climate change.

In that long process, we will generate ruins. We will have to acknowledge that maybe a lot of the materiality that we even have gotten used to and appreciate, like the technology that is supporting our discussion today, might become part of these ruins. I think that’s where social ecology and social metabolism are useful. It’s like there’s no easy way out of this type of conclusion.

Socialism is not just the Soviets’ radical workplace, democracy, and electricity. It’s going to be much more complicated. It’s also, I think, a criticism and an antidote to the easy solutions proposed by the people around, I would say, the Green New Deal approach, who are basically saying, just convert the grid to renewable energy, and everything’s going to be fine. The material change is very deep.

I think the vocabulary can be used as a planning instrument. I think that if we do democratically want to change the metabolism of our society if we do want to learn to live within limits which we will discover and set for ourselves because nature will not give us limits. Nature will just change. There are no limits out there in nature; that’s not the way it works. What works is that we will discover the limits that we have to impose on ourselves because otherwise, we will create natures in which we will not be able to exist, but maybe other life forms will be able to exist. So if we don’t want to end up in a world in which we cannot exist, then we have to set limits to our activities. Social metabolism gives us the tools to debate these limits and to see the materiality of our society.

In the book, I propose some tools, but there’s so much more out there. I propose mostly a perspective. We have to look at the materiality, and we have to look at it in a lucid manner. This lucidity comes through this very dry and, I would say, gray vocabulary of material stocks and flows. That if you have built up a city out of concrete that is very dense with buildings that are 40-50 stories high, then you need a lot of energy to keep that thing going. You’ve locked inflows. There is no other way around it. If you move away from that towards something that is different, that implies less density, that has got more nature in it, then you might need less of these flows, but you might need more human labor. Then we’re faced with choices.

We’ve moved away from human labor directly engaging with nature in ecological relations. We’ve built up our society and our notions of progress around human labor, interacting with the Earth through geological relations, extracting stuff, building it up, using the stuff we extract to labor less, us, the privileged, even though three-quarters of humanity is laboring a lot so that we can labor less. Three-quarters imply people in our own societies: waste workers, people that are working in the fields to generate the food that we eat.

I think that one of the, I would say, important messages of the Social Ecology of Capital is that we have to reconsider this notion of progress, moving from the ecological to the geological and moving back into ecological relations with nature with what we call nature in our societies, other societies have other words. Nature is really modern and Western, but that’s what we have as a word, so let’s use it. These ecological relations will imply new imaginaries of activities. Let us maybe end it with that, and that’s something that I argue in the book.

I think there we have a lot to learn and draw from feminist work on reproductive activities and reproductivity as a concept and the care that goes into that and the way we understand labor in a reproductive context, which is very different from labor understood as an extractive activity. I touch on this in the introduction. I use it a bit in certain chapters, but I think there we have to read feminist economists and feminist theorists that can really help us move into this new way of understanding our metabolism as we move into more ecological relations again.

Talia Baroncelli

Right, and that approach would also problematize ideas of measuring economic growth in terms of GDP, growth domestic product, because that doesn’t really take into account reproductive labor, the value of childcare, care work, and that sort of thing. That is all missing.

Éric Pineault

Yeah. Basically, what the GDP does is it calculates what we cut out of our social activities. It basically calculates the frontier or the border that we put between productive and reproductive. It calculates what we devalue as non-economic, which is all the care. It says, okay, once we’ve cut all that out, we take a cookie cutter, there’s the cookie; that’s value. The rest just doesn’t exist. That’s what GDP does. It’s horrible. It’s a horrible metric. I use it as the metric to understand the degree of commercialization in a society. The degree of penetration of capital in our social relations is brilliantly measured by GDP. That’s what it’s good for.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, perhaps next time, we could speak about other terms to use as opposed to GDP and also speak about this feminist approach that’s missing widely in the discourse and also how social metabolism and ecologies or economies of extraction are heavily built on hierarchies of gendered hierarchies, racialized hierarchies. So maybe another time we could speak about that.

Éric Pineault

Yeah, and bring other voices, too. A lot of voices could speak to these questions a lot more than me. But I could also, yeah, it’s something that really interests me, and I think it’s highly important. Then maybe one last word. This brings us to, and I conclude also with this in the book, degrowth. Degrowth is not a slogan or an end in itself but is the idea that we have to move out of the growth paradigm to think of emancipation. We have to think emancipation beyond growth. That’s really what I try to end with.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, that’s a great way to end emancipation beyond growth. Thank you so much, Professor Pineault, for joining theAnalysis. It was really great to have you on and to speak about these, I think, dense issues but incredibly relevant to our time. So thank you so much.

Éric Pineault

You’re welcome.

Talia Baroncelli

Thank you for watching theAnalysis.news. If you enjoyed this content on The Social Ecology of Capital, please go to our website, theAnalysis.news, and consider donating to the show. You can also get on our mailing list to ensure that you’re notified every time a new episode drops. Also, go to our YouTube channel, theAnalysis-news. Like the channel and subscribe, and hit the bell. That way, you’re notified next time there’s a new episode. See you again. Take care.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | TuneIn | Deezer | RSS

Never miss another story

Subscribe to theAnalysis.news – Newsletter

“Eric Pineault is a professor at the University of Québec in Montréal, where he teaches political economy in the Department of Sociology and ecological economics in the Environmental Sciences Institute. His current research focuses on the political economy of the ecological transition in Canada and of the extractive sector in Canada and globally. He has recently published Le piège Énergie Est with Écosociété, a book that critically examines the proposed Energy East pipeline project. Eric is a core team member of the Corporate Mapping Project.”