Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | Email | TuneIn | Deezer | RSS

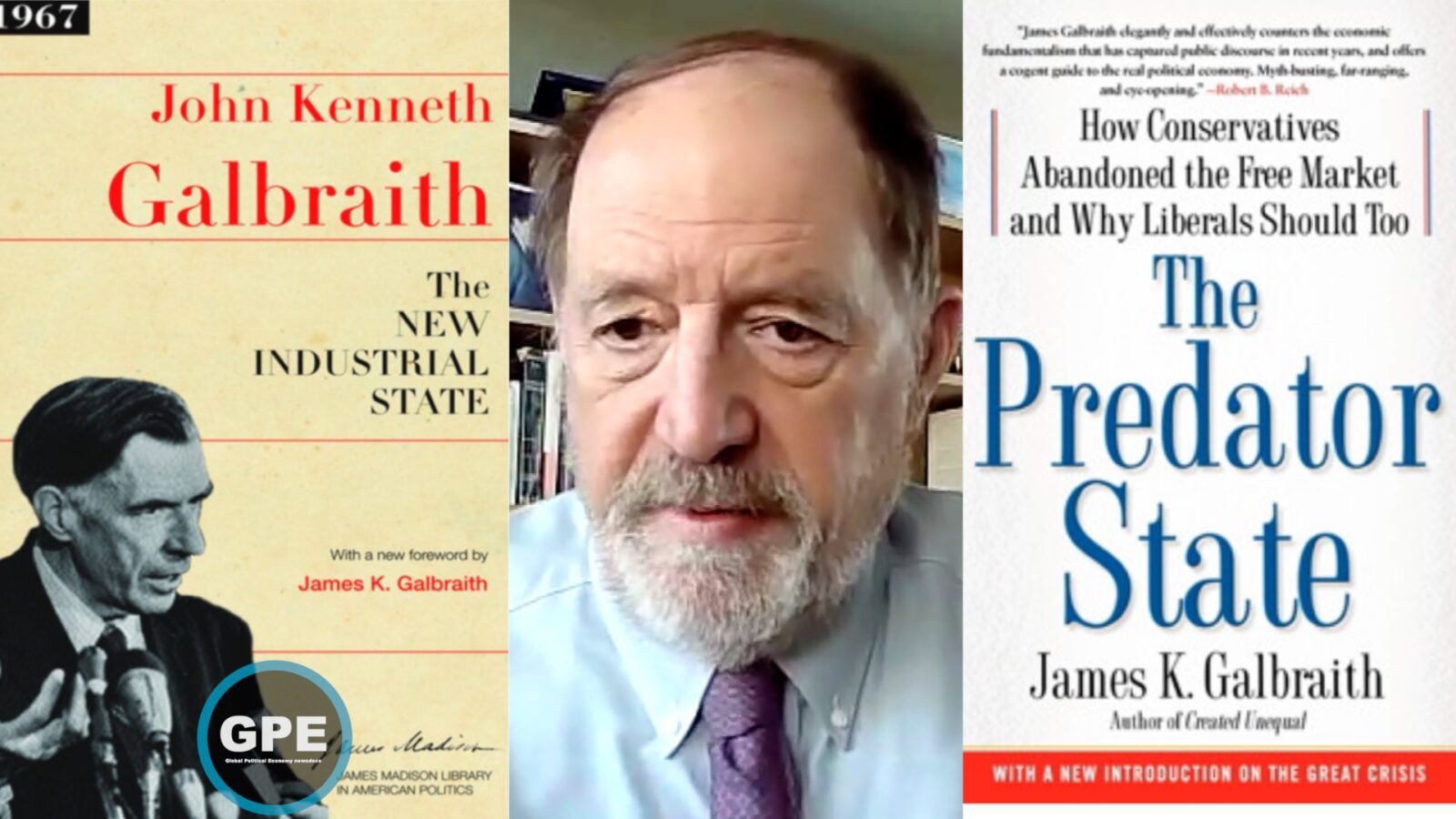

James K. Galbraith discusses the shift of US capitalism from an industrial state to what he calls a predator state: a finance-led, military-centered corporate republic that continues to prevail. To overcome it, he lays out what is needed to focus on employment, stability and adjustments to rising resource costs. Lynn Fries interviews Galbraith on GPEnewsdocs.

TRANSCRIPT

LYNN FRIES: Hello and welcome. I’m Lynn Fries producer of Global Political Economy or GPEnewsdocs with guest James Galbraith.

It is normally thought that large investments and technological developments can ensure fast economic growth and prosperity. In the book The End of Normal, James Galbraith argues that while fixed-capital and embedded technology may be essential in a capitalist system, rising resource costs can render any such arrangement fragile. [1]

As it is not possible to obtain cheap resources indefinitely, be it domestically or from the rest of the world notably the Global South, Galbraith argues that the US needs to design institutions and policies to cope with rising resource costs. Not doing so has been one important reason that explains the shift from the American capitalism as described by John Kenneth Galbraith in his 1967 book The New Industrial State to an economy shaped by crises, institutional breakdowns and predatory tendencies, as described by James K. Galbraith in his 2008 book The Predator State.

In today’s program, James Galbraith analyses this long-term transformation of the US economy, describes its current state as a corporate republic in which finance has gained the upper hand and co-opted democratic institutions to forward its narrow interests, and discusses solutions for the way forward, which will also re-shape the future of growth.

Joining us from Texas, our guest, James K Galbraith holds the Lloyd M. Bentsen Jr. Chair in Government/Business Relations and is Professor of Government at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin. A prolific author, James Galbraith’s published work includes The End of Normal, Inequality and Instability and The Predator State among numerous other books.

Welcome, James.

JAMES K. GALBRAITH: Thank you.

FRIES: Let’s start with some context on the analysis of American Capitalism presented in The End of Normal. In your words: “this is the economics of organizations developed by John Kenneth Galbraith modified to emphasize that large, complex systems are not only efficient but also rigid…”.[2] The economics of organizations is a concept developed in The New Industrial State and John Kenneth Galbraith of course was your father. Let’s start there. Tell us something about that body of work and related terms like technostructure and countervailing power that John Kenneth Galbraith coined in his analysis of American capitalism.

GALBRAITH: The New Industrial State was the culminating book of a trilogy essentially that my father started in 1952 and completed in 1967. The three books were American Capitalism, the concept of countervailing power, The Affluent Society and The New Industrial State.

And what he developed in that body of work was a portrait of how American capitalism actually worked. And it was clear that it was an industrial capitalism that was rooted in the functioning of large organizations of large industrial corporations. And not in this notion that really was a hangover from the 18th century of essentially independent, small businesses and farmers and so forth all transacting with the so-called market as the dominant institution.

You can’t do advanced production/advanced manufacturing that way, because you have to have a mastery of a whole raft of technologies. And in order to do that, you have to have specialists. In order to have specialists and use them, you have to give them very specific things to do. Someone does the chemistry, someone does metallurgy, Someone does the engineering, hydrodynamics and on and on and on. to bring this all together. And that has to happen in an organization.

And then when the organization actually masters the technology, it has to figure out a way to present it to the public so the public is interested in buying it. It has to manage a regulatory process. It has to manage the financial aspects. It has a whole range of functions that go beyond the pure matters of mastering the technical aspects of production.

So the technostructure, (which was by the way, not my father’s, um, most felicitous coinage. And he was somewhat ambivalent about it as well as a word), [the technostructure] is a group of people who make up as a group the functioning brain of a large organization. And one of the ideas in The New Industrial State was that this group of people were really the governing force.

They were the ones on whom the organization depended. That the top manager, the person, the CEO, the so-called entrepreneur was somebody who could be replaced generally speaking. The Board of Directors didn’t really do anything at all. It was a symbolic body. The shareholders had no role.

The people who actually ran the show were the people who knew how to fit the pieces together and could work together as a team. And that was the message of The New Industrial State.

And that was also the dominant feature of the whole American capitalist system. On the one hand you had the alternative, which was the Soviet Union which was an industrial and behemoth but very centralized and very rigid. And obviously at the end of the day, very fragile. And on the other, you had the developing world which hadn’t mastered the capacities that the American corporation mastered.

So the US system at that time was widely regarded as being a model toward which effective developmental strategies would be attempting to trend. All of that, of course, has changed. The world does not stay still and nobody captures it for any indefinite period of time.

FRIES: Give us more background on the development of the US system and so what were the decades spanned your father’s portrait of American capitalism.

GALBRAITH: Well, the development of the system does start really in the early 1930s. It starts with Roosevelt’s New Deal. I mean, you had an earlier system which was very unstable; which went through an explosive period of growth in the 1920s and then collapsed. And the collapse didn’t go away. It lasted for four very long and painful years in which the factories were idle and the people on the farms couldn’t sell their products and then there was mass migration and all kinds of ecological disaster.

Then Roosevelt in the New Deal created an entirely different structure within which the American economy could function. And that was a federal project and it culminated in the vast industrial mobilization at the time of the Second World War.

So the period my father is describing really picks up from I would say from the early 1940s, when he himself actually played an important role. He was the deputy administrator for prices of the Office of Price Administration. So he controlled basically every price in America for a period of a year. Then he went onto describe the system that he’d had to deal with and that was evolving in the forties and into the fifties.

It’s about managing the uncertainties associated with advanced technology. It’s about having organizations that are stable, that provide livelihoods that are stable. It’s about organizations that are responsive to multiple constituencies, the public sector, to the consumer sector, to various outside forces.

So it’s about the balance of things in society. That’s the concept of countervailing power. It’s about having essentially a world in which you have some economic predictability, not only for the organizations but for the people who work for them and for the larger community.

And again, all of that was certainly the way the system appeared to be functioning into sixties. And then into the seventies it began to run into the kinds of serious difficulties which have been a feature of life for the last 50 years.

FRIES: As you argue in The End of Normal, in the postwar era, economists were living in a kind of dream world because the dominant economic ideology basically obliterated the analysis of resource costs from economic growth theory. This vision then just assumed as you say that the rapid economic growth performance of that period could be pursued indefinitely and extended to everybody.

One of the consequences being the US postwar economic system didn’t get built to cope with rising resource costs. The implications of which did not surface until cheap resources that had enabled rapid growth in the postwar era were no longer so cheap in the 1970s.

GALBRAITH: A couple of distinct points here. The early 1970s were characterized by some epochal changes. The first one in 1970 itself was the peak in conventional oil production in the United States. Which meant that from that point forward, we were increasingly dependent upon imported oil Middle Eastern oil.

In 1971 the exchange rate system that had been developed after World War II broke down. It was dismantled by President Nixon. The dollar was devalued and you had the beginning of a period of substantial instability. This led in 1973 to a big increase in the price of oil. And that was the first energy crisis.

And what did that do? That meant that a great many American industries which had been built on high levels of of energy consumption now had very high costs compared to other industrial structures that were more recent. Or that were being built at that time which could be built to adjust to the higher levels of energy costs.

Which was true of the automobile industry in Japan, for example. Since Japan didn’t come out of the war with a great reserve of cheap energy, it always had to be conscious of that in building up the kinds of industry, automobile industry for example, that it built. And so it was, it was in some sense, better adapted to the new environment.

And here you had two different or two let’s say industrial systems which we’re organized by different corporations, under different governmental structures, which were in alliance with each other, but we’re also in competition. And from that point forward, you began to see this real incursion of German, Japanese and later Korean and then finally much later on then the Chinese industrial organizations and production structures send products into the American market.

And they tended to displace those parts of the American industry which were older, organized under the principles that had been advantageous in the fifties and sixties. And you got a kind of de-industrialization that occurred in the United States. And then greatly accelerated in the 1980s by the way economic policy was managed.

FRIES: I’ll just interject for viewers here that we cannot possibly do justice to the full breadth of your analysis not least of all the international dimension But I’ll just note here that as well as hollowing out the US industrial core, the way US economic policy was managed in the ‘80s set off a debt crisis that went around the world for two decades and was especially devastating for the developing countries in the Global South.

Talk now about the financialization of the US economy following this period of accelerated de-industrialization in the 1980s. So after the industrial core of the United States, so basically that means the agro-industrial middle class economy from the 1930s to the 1970s, was gone. So what then emerged in the 1990s?

GALBRAITH: I published a book in 1989 whose subtitle was Technology, Finance and the American Future that I think captured what was about to happen or what was already already happening at that point. The economy that returned in the context of the 1990s was a very different economy.

It was dominated by global finance which was headquartered, of course, in New York on the East Coast of the United States. Its major industrial element in the United States was no longer in the upper Midwest and no longer basic consumer goods manufacturing, but the technology sector, which is much more located on the West Coast. So, you had aerospace; you had information technology; you had armaments; you had the entertainment industry.

These things prospered under these conditions. They were highly oriented toward global markets. They were also strongly backed by the financial sector. So those two things became in some sense the controlling, the dominant elements in the American place in the world economy. With a great many of the consumer goods coming in from overseas in a way they had not done before.

FRIES: Well that gives us an overview of American capitalism as it evolved from the postwar era into the 1990s. So as further context to the 1990s, let’s bring the Soviet Union into the picture here.

Earlier in the conversation, you said the late Soviet Union was an industrial behemoth but very centralized and very rigid. And so obviously at the end of the day, very fragile. Notably because it was a single integrated high fixed cost industrial system which operated with very little flexibility.

So the question being, do you see any convergence between the late Soviet model and what happened in the United States?

GALBRAITH: Well, there was certainly in both systems a process of obsolescence. And let’s say the downfall of industrial systems that were built up in the first half of the 20th century were no longer effective under the conditions in the second half of the 20th century. So that’s certainly true.

The situation in the Soviet Union was much more dire because among other things, the entire country collapsed in 1991. And that broke apart industrial chains of production which had previously been within one country. They had to cross international frontiers. As national frontiers turn hostile in some cases, the system no longer works. The same thing happened by the way in Yugoslavia.

And the Soviet system was more brittle in important other ways and suffered a much more calamitous collapse. This was a system which, although it had many inefficiencies, it was designed to take advantage of certain kinds of efficiency, particularly very large-scale operations: steel plants, automobile plants, and so on and so forth.

And that was what generated the fragility that led to this breakdown at the end of the Soviet period. From which Russia by the way, over 20 years has substantially now recovered. But, that was the situation at the time.

But what happened in the United States was not of an entirely different type. It’s just that the US had elements that were able to recover and maintain their position in the world economy. And again, the dominant ones were finance, technology. But they were located in very different parts of the country. So you had essentially a large area of economic stagnation and decay.

And that of course, has its political consequences. It’s what led ultimately to what Donald Trump was able to seize upon in 2016 and carried him to the presidency. Before that these developments were what, for example again, carried bill Clinton to the presidency. His strength was on the East Coast, on the West Coast and bringing that into the Democratic Party. Each of these economic developments has a political corollary which you can trace very easily.

FRIES: Let’s turn now to the shift from the form of American capitalism described by your father in The New Industrial State to what you describe in The Predator State as a corporate republic. So talk now about your argument that when weakened by adversity, the US model was destabilized from within and made vulnerable to fraud, predation, and looting.

GALBRAITH: Here’s another case where we can talk a little bit about convergence between the late Soviet model and what happened in the United States. In the Soviet Union when it was no longer profitable or no longer possible to produce in the previously existing structures, the people who had control of the assets liquidated them.

It was called the privatizing nomenclature. They simply enriched themselves at the expense of they previous existing system at the expense of everybody who had been dependent upon it. This contributed greatly to the social distress and to the collapse of life expectancy and so forth in the late Soviet period.

In the United States what I described in my 2008 book, The Predator State, was something about essentially a parasitism on the public institutions that had been developed in the New Deal and the Great Society. The argument I was making was that we had very robust social insurance, social stabilizing institutions including Social Security, Medicare. One could go down the list.

And a certain politics emerged out of that. Free market conservatives might say we want to get rid of these things. We want to privatize them. We want to dismantle them altogether. That isn’t really what they were after. What they realized in this age of particularly George W. Bush and Dick Cheney was that they could make certain parts of their constituency quite happy by skimming. Essentially by taking some of the resource flow and directing it to the narrow constituencies that supported them.

So this was the case, for example of Medicare Part D, which is the drug benefit that was a major expansion of Medicare that occurred under the Bush administration. It became a very complicated system with a lot of private drug companies making a lot of money off of selling pharmaceuticals to senior citizens in the United States. They pay an enormous amount. It’s just unheard of certainly in Europe in terms of what these medicines cost. And that’s not accidental.

The whole idea here is that you get private sector support for the larger program by enriching a small group of people, at the expense of the larger public. It’s not a system, anybody who designed rationally, but from a political standpoint, it makes sense. And it’s understandable that any kind of, let’s say an administration with the ethics of the George W. Bush administration would pursue that road.

And so we saw quite a lot of that. Essentially, as I say, not undoing the public sector but converting it into an instrument that also greatly enriched private interests.

That said one also had in the strictly private sector, there’s nothing quite like… I wouldn’t call anything strictly private, but in the corporate sector, we also went through a period of basically the dismantling of going concerns in order to enrich shareholders and corporate executives who were able to self deal with stock options and buybacks.

The whole business of private equity is largely concerned with that. How do you load up an organization with debt in order basically to walk off with a great deal of the asset value. So you see a great deal of that going on as well.

FRIES: You distinguish between those nations that continued along the lines that once defined US economic success as described by John Kenneth Galbraith in contrast to those that like the US & UK, shifted to the opposing Friedman doctrine of the economics of markets.

Prominent examples of nations that continued along the lines of the Galbraithian the economics of organizations being Germany, Japan, South Korea, and China. So comment on John Kenneth Galbraith’s influence in that respect and specifically in the case of China.

GALBRAITH: Well to begin with it wasn’t my father who directly advised the Chinese. Actually, I did that. In the 1990’s I had for four years a position in a consultancy under the United Nations Development Program as chief technical advisor to the State Planning Commission for Macroeconomic Reform. It was mostly an exercise in providing training and exposure to the people who were working there, rather than direct policy advice.

The interesting thing though is that when I got there in 1993, I got a whiff of a fact that I’ve later confirmed through the work of a young economist named Isabella Weber who has written on this in a very important book about China. The people I was dealing with were very, very familiar, especially, with the American experience with price control in the Second World War. Which was my father’s doing.

And the things that they knew about it were what he’d written about it. And they had his books. They’d been translated internally. They’d studied them. And so this fed into if you like the historic Chinese economic management. Which has always been about stabilizing prices, agricultural prices and then the new problem was industrial prices. And that’s where they drew on my father’s work.

That approach is completely opposite to the idea in Western economics that the prices are supposed to adjust. And that the markets are supposed to, you know, let them go up and down and do whatever. Now that’s just not the way it works.

In the thousands of years of Chinese history, the emperor has always bought the grain when it was cheap and sold it when it was expensive in order to keep the peasants from rising up in revolt. And by and large, it worked. So this is a big difference.

I characterize the economies of a number of countries as Galbraithian. In Germany where you have co determination and strong unions. And you have a kind of collaboration between the industrial and the union and the government sectors. At least in the, in the traditional part of the German economy. In Japan, Korea, and I think China fits under this rubric as well. In which fundamentally the driving forces in the economy are industrial organizations, corporations; some of them State owned, some of them private, some of them joint ventures, some of them foreign. But they maintain long-term objectives. They’re not quick buck operations.

The government has been quite careful to prevent or to restrain the tendency for asset stripping that comes up in capitalist systems. And China has a very substantial capitalist system. The notion that it is a communist country is not something that’s recognized by anybody who knows it well.

This is the big difference. It’s not a country where the equivalent of Wall Street runs the show. It does have its own financial sector. The government has been quite careful to keep it from taking on the kind of overwhelming importance that the financial sector has in the United States or the United Kingdom. And that’s a big difference. That’s a Galbraithian feature, if you like, of the Chinese system.

FRIES: And how is China coping with rising resource costs?

GALBRAITH: Well, the Chinese have been planning for the resource issues and acting on those plans. That’s what the Belt and Road Initiative is largely about. It’s about building pipelines and rail lines and so forth that will supply ports and mines and so forth in resource producing countries. That will establish reliable supply lines so that China can navigate what they anticipate to be a period of rising resource costs because they know they have to reduce their reliance on coal. Coal is the cheap fuel.

But if you’re going to use a gas, you’re going to get it from Russia or from central Asia. And the other things that one needs are going to come from other parts of the world, Africa, notably. And so you see the Chinese going out there and saying: Hey, we’ll build you ports and airports and so forth, rail lines, roads. And making these deals.

They’re doing this very much in their own interest. And the interest of long-term stability of their supply lines. We accuse them of having lots of other motives but it seems to me that this is clearly the dominant motive of Chinese engagement in the developing world.

FRIES: In contrast then to a number of countries that you characterize as Galbraithian in the US, Wall Street runs the show. Your argument is that the US needs to move to a qualitatively form of American capitalism and a new approach to economics is needed for that to happen. And your own approach is to treat the economy as having the same form as a biophysical system. So tell us something about that.

GALBRAITH: This is an argument that I’ve developed in conjunction with a colleague of mine, Jing Chen. And it’s rooted in the most basic physical principles. That in order to extract resources efficiently, you have to invest. There’s no other way of doing it. And then the large scale investments are the most efficient ones.

And when resource costs are low, it just pays. It pays to build when you have a large free-flowing river coming through a canyon with a lot of energy available, it pays to build a big hydroelectric dam. And that’s a capital intensive enterprise. One can go down the list of things of that kind.

The consequence of doing that is that when the resource costs go up, then you’re in a dangerous situation. That’s in the nature of every physical, biological, mechanical system. It’s not accidental that the largest animals have the biggest range and the most diverse diets and so forth. But it is also not accidental that they’re the ones who are endangered. And that they’re the ones who at risk when the climate changes.

FRIES: Talk more about the basic physical principles in this approach that treats the economy as having the same form as a biophysical system [3]. In other words, what all that means.

GALBRAITH: Well, it means that you have to build the economy in conjunction with the environment of which it is a part. Both the resource environment and what’s available in terms of the biosphere for absorbing the waste products of economic activity. And those two things have to be treated as of really great importance. Which we haven’t been doing.

In terms of how economics should be taught and understood, it seems to me that giving everybody grounding in thermodynamics is vital. And understanding that the economics that is in the textbooks is a kind of 18th century idealization. It’s really pre-scientific. It has a theological aspect. It’s sort of Deist. That’s what Adam Smith was.

In some sense, it’s the intelligent design view of the economic world. Which was superseded in scientific understanding already in the middle of the 19th century by Darwin and evolutionary perspective.

So what I’m building on and suggesting is that once you really start with the essence of an evolutionary perspective and get people to understand what that entails.

FRIES: Explain more about that. So give us some context on what an evolutionary perspective entails.

GALBRAITH: First of all, we have to recognize we have some obligations to the planet. Those obligations are to move away from the cheap and dirty fuels. And to create systems that are sustainable over a long period of time. This is partly an engineering problem but it also is a question of resource allocation.

And you’re going to have to put resources into that to make it happen. Economists talk rather glibly about carbon taxes and say: Okay, we can get the price of using carbon up. But it doesn’t work that way. People who own a gasoline powered car cannot immediately switch to something else. It’s not as though they have a horse in the backyard that doesn’t emit carbon dioxide.

So, one has to build systems that are functional. And in order to do that, you’ll have to commit resources. In committing resources, you’re going to have a lot of things that are you’re using resources for that are not immediately consumable. And they will yield benefits down the road. And so you have to manage that transition.

Is it entirely new? No, nothing’s entirely new. This is part of the problem that was dealt with in the Second World War. It was part of the problem that was dealt with in the construction of the infrastructure of the country in the New Deal.

FRIES: Let’s talk more about your argument that in order to move to a qualitatively different form of American capitalism, a new approach to economics and so economic growth strategy is needed. By now most everybody recognizes the problem of boom bust economic growth. Your critique of finance driven growth and the role the wave of financial fraud played in the 2008-2009 Great Financial Crisis is also widely recognized.

Of special relevance to this conversation is your argument that these financial frauds were the culminating phase of efforts to preserve the post war rapid economic growth performance. So the culminating phase of decades of efforts basically from the 1970s when American capitalism ran into serious difficulties. As discussed earlier, the postwar era of easy growth enabled by cheap resources ended with the rise of resource costs in the 1970s.

So to have another stab at some of the underlying insights of your critique of efforts to sustain a high economic growth, I’ll very quickly cite from your book The End of Normal. In your words: A high-growth economic strategy favors capital investment, a substitution of capital and energy for labor, and fosters increased inequality in a winner-take-all-system. [4]

You point out that finance and technology, two sectors that dominate this winner-take-all-system simply don’t provide a large base of direct employment. So focus for a moment, on the issue of productive employment under this high growth model.

One thing we can all understand is a low use of labor compared with machinery and resources has implications for working people. Taking the case of labor saving technology, talk about how the advanced technology sector is accelerating a decline in the base of productive employment.

GALBRAITH: This is a feature of essentially the wave of technologies that we’ve been in the midst of for the last 25 or 30 years, at least.

I’ll put it this way, if you look at what happened in the early 20th century a great many things that were provided within the household were outsourced to machines.

Transportation was one of them. My father grew up on a farm where the the plowing was done by teams of horses and you don’t need a gas station and you didn’t need a mechanic. These were replaced by tractors and the carriage into town was replaced by the automobile. And a whole body of not just producing the employment producing these vehicles but in maintaining them and the roads and the fuel systems and everything else grew up.

So the system was adding employed paid jobs. And one could go through a lot of things that happened inside the house as well. That you know, cooking and cleaning and so forth. Where it became mechanized and became the objects of employment providing industries.

Now this is not what the digital world is doing. It seems to me. What the digital world is doing. And the digital revolution is doing is working out ways to reduce the labor content of a whole range of things. I mean, we can go down enormous lists. But a lot of clerical work, a lot of accounting work, a lot of communications, obviously the information and the entertainment sectors and all kinds of things.

What we’re doing right now, which is talking over a digital link would have only a few years ago required airfares, hotels, restaurant bills, all kinds of things in order to do this. And even though the underlying recording technologies existed for many decades.

So one can see that the ancillary labor requirements are being reduced. Which is not a bad thing. It means that lots of things are becoming accessible, simple, and inexpensive to do that were previously clearly quite expensive and difficult.

But it does mean that we have to adjust. We have to work out things for people to do that are not automated; there are many things. Life can go on in a very agreeable way. And in fact can be improved dramatically provided that the economy is able to give a means of subsistence; make incomes flow for doing those things.

And if the industrial model isn’t going to be providing a lot of jobs, then we have to have institutions that do. And cooperatives are an example and decentralized public sector structures of one kind or another. are an example. The tax system can be mobilized to assist this. We just have to put our minds to it.

FRIES: What you are describing basically means turning the prevailing high growth strategy on its head to what you call a slow growth strategy. Which is not a slowed version of the high growth strategy but instead as you explain, to quickly cite from The End of Normal once again: A slow growth model should instead foster a qualitatively different form of capitalism: based on decentralized economic units with relatively low fixed costs, relatively high use of labor compared with machinery and resources, relatively low rates of return, but mutually supported by a framework of labor standards and social protections. {5]

GALBRAITH: I stand by those words. I think one does need to recognize that some parts of that economy are going to be of a very high fixed cost variety. Entities that actually create the information networks, these are laying down fixed cost systems. The entities that will continue to provide manufactured goods may not be very large in terms of the scale of employment, but they will be very concentrated in their use of capital and technology, otherwise they won’t be able to do this.

They’re going to be complex, concentrated and effectively centrally organized. There’s no I think way around that in the modern world. You don’t want to have excessively duplicative network structures beyond what you need to have a certain amount of resiliency.

So there is an illusion, which I would associate with some of the people who are the advocates of this so-called new antitrust, that the problem is concentration per se. And that the way to deal with this is to establish competition, to have many, many units that are effectively all trying to do the same thing. And this is not an effective way to organize, for example, a communication network. If you had 10 Facebooks or 10 Googles 9 of them would not last for very long, no matter what you did.

So one has to really push back against the idea that the 18th century economic idea had it right That idea was already out of date with the Industrial Revolution. So, what is the right approach?

I think the right approach is, again, a Galbraithian approach. It is to recognize the need for countervailing power. To recognize the need for public purpose and for effective and autonomous regulatory structures that can make these large entities serve a public interest.

You have to recognize there is such a thing as a public interest. It needs to be defined in a coherent way. It needs to be respectful of individual rights and protected from abuse. But there is a public purpose and there is a public interest and some entities and institutions need to represent it. And so you really have to have people who are competent and who are trained, who are dedicated, who are imbued with a public spirit, who have enforcement authority setting a set of rules and making and trying to ensure that they’re actually respected.

By the way, this is most especially true with the financial sector. If the financial sector is controlling its own regulations then you’re going to end up with one financial crisis and disaster after another. And the only way to avoid that, that actually works, that has a demonstrated record of working, is to have a set of regulatory institutions that are fully independent and that have real authority over the behavior of the large financial institutions. And can keep them from essentially abusing the enormous control and authority they have over the extension of loans and what effectively has been the creation of money.

FRIES: So in The End of Normal you analyze the breakdown of law and ethics in the financial sector as one of four major obstacles to sustainable growth and full employment in the US. Two others being, as we discussed, the rising costs of real resources and the labor-saving consequences of the digital revolution. Talk now about the fourth. What in your words is: the now evident futility of military power.

GALBRAITH: A great deal, at least a strong part of the deep backbone of the American economy in the post-war period was furnished by the military position of the United States, by the security environment that emerged out of the war and then was built up in the Cold War. And then in the aftermath of the Cold War got completely out of hand.

There was an idea that the United States was the sole superpower. It was going to essentially provide the guarantee of world security. And an idea that the US military was the the hyperpower or one that nobody would stand up to.

It’s now 30 years down the road from the emergence of those ideas in the early 1990s. And we see that they are both in tatters. They both have been effectively refuted. The United States is not being accepted as the sole guarantor of global security. And in fact, strong powers have emerged which are not going to accept it and insist that the world be organized on principles that are multilateral.

And secondly, it has been demonstrated that for all of its professional commitments and so forth the American military was unable to prevail in Afghanistan and was unable to prevail on a sustained basis in Iraq.

It’s quite clear. And I actually was invited to give this presentation in 2004 to a group of military officers in Germany. And I made the point, which I developed in the book, that in the modern world the military advantage is with the defense. It’s with those who control their own territory. Because first of all, it’s technology. Secondly, it’s the expectation that at the end of the day, they’re going to be the ones who are going to still be there. That nobody’s going to stay on somebody else’s territory indefinitely.

And so we shouldn’t expect that the security arrangements for the world can be like what we imagined, what some people imagined they would be 30 years ago. We have to come to grips with this. It means we really should for our own sake and for the sake of our economy completely reconfigure our military posture; recognize lots of things that we have are not, not going to be useful.

And we need to build a global security framework which takes account of the power centers that have emerged which we need to accept and deal with. We did this in the Cold War when the Soviet Union was essentially the major security partner, adversary, however you want to describe it. Essentially a balance of power, not a particularly happy one, but one which kept conflict down, did develop.

We need to recognize that we’re not going to escape having to do that again. And maybe you don’t like the countries that you deal with, but that’s not the point. You have to deal with them. And you have to come to the best security arrangements you can achieve. We can’t pretend that it is within our power to prevent that.

I think that understanding that is as an element actually of a sensible economic development strategy. Because when you free up the resources that you’ve been putting unproductively into let’s say armaments technology and into the human parts of the military establishment and into the bases that we maintain everywhere. Then you have resources that you can mobilize for other purposes where they can be more effectively used for the benefit of everybody.

FRIES: This then as you say would be an element of a sensible economic development strategy. And as we are talking about the US, you use the word development strategy in the context of a high income, advanced economy. So this would be an element that is part of a constellation of policy advice that you’ve developed as the way forward for the US. As we’re wrapping up, give us an idea of the main thrust of all this. So, what are some main objectives of these policy solutions?

GALBRAITH: In terms of policy and I am by and large a policy economist and not so much a high theorist. In terms of policy, since you recognize that resource constraints are going to be there and you have to deal with them, one should orient consumption patterns as far as possible toward things that can be enjoyed collectively, toward public goods, in other words. The quality of the environment in other words is a substitute for the accumulation of privately held objects. And something which can be provided I think at considerably more resource efficiency than the current system does. That’s true of transportation networks, for example, that’s a very important element in this. So that’s one thing.

And the second thing I think we need to recognize is that in an economy in which material goods are produced by very small numbers of people and often not within the boundaries of the country consuming them, then you need to provide a strong and a very robust security: social insurance, personal security, security of food, of housing, of retirement, access to education and cultural opportunities to the broad population.

That was the great accomplishment of the New Deal to get that process started. It’s by no means complete. But it gives people the chance to lead fulfilling lives; to take a certain amount of personal risk. Because they’re insured against some of the worst outcomes. To be assured that they will get healthcare when they need it. To protect people essentially against the forces of financial rapacity that’s inflicted on them with student debt, with healthcare debt, with old age insecurity. These are things we ought to be trying to banish.

FRIES: James Galbraith, thank you.

GALBRAITH: Thank you.

FRIES: And from Geneva, Switzerland thank you for joining us in this segment of GPEnewsdocs.

(Visual content cited from The End of Normal by James K. Galbraith: [1],[2],[3] p237 & [4],[5] p252-253)

END OF TRANSCRIPT

James K. Galbraith holds the Lloyd M. Bentsen Jr. Chair in Government/Business Relations at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs and a professorship in Government at The University of Texas at Austin. He was executive director of the Joint Economic Committee of the United States Congress in the early 1980s. He served as chief technical adviser for macroeconomic reform to China’s State Planning Commission. His books include: Welcome to the Poisoned Chalice: The Destruction of Greece and the Future of Europe (2016), Inequality: What Everyone Needs to Know (2016), The End of Normal: The Great Crisis and the Future of Growth (2014), Inequality and Instability: A Study of the World Economy Just Before the Great Crisis (2012), The Predator State: How Conservatives Abandoned the Free Market and Why Liberals Should Too (2008).

Watch the documentary The Con about the massive bank fraud that created the 2007-2008 housing crisis. Then watch the accompanying documentary, The New Untouchables about the local authorities who tried to stop it.

When Dr Galbraith talks about replacing the former industrial basis of employment, I wanted to respond that the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) economists I follow, like Warren Mosler, have suggested that we should have a Federal Guaranteed Job Program (FGJP) that would hire people to do anything that was beneficial to the local community, such as caring for an elderly parent or disabled spouse, and that the FGJP would set the base wage at an acceptable level, well above subsistence. Private employers could still hire labor, but they would have to pay enough to compete with the base pay of the FGJP.

I think that this idea fulfills the system that Dr Galbraith proposes.

The “slow-growth” model