Talia Baroncelli interviews historian Pouya Alimagham about the historical context of the current Iranian uprising.

Talia Baroncelli

Hi, I’m Talia Baroncelli, and you’re watching theAnalysis.news. I’ll shortly be joined by Pouya Alimagham to discuss the protests in Iran, as well as the history which led up to them. But first, please don’t forget to go to our website, theAnalysis.news, hit the donate button, and subscribe to our newsletter. I’ll be back in a bit.

I’m very excited to be joined by Pouya Alimagham. He’s a historian and a lecturer on the modern Middle East at MIT, and he’s also the author of the book Contesting the Iranian Revolution: The Green Uprisings. Thanks so much for joining me, Pouya.

Pouya Alimagham

It’s good to be here. Thank you.

Talia Baroncelli

So I wanted to ask you about the current protests. Right now, we’re about three months into the protest. It’s been three months since Mahsa Amini was killed by the morality police. Over 100s, or actually almost 500 people, have been killed now during the protests, and we’ve seen two people being executed. So I was wondering if you think the protests will continue to have momentum or if they’ll be driven underground.

Pouya Alimagham

It’s a good question. Momentum doesn’t necessarily have to be every day. We’ve seen the uprising. We’re actually in the 96th day of it. It has a lot of ebbs and flows. Every Friday is a big spike, especially in places like Zahedan, where they gather for Friday prayers, and then right afterward, they protest, especially the Baluchis, they protest.

The repression is real, though. When you have a disorganized movement, and when I say disorganized, I’m not trying to knock it. I’m not trying to say that it’s ineffective or there’s no organization, but organizations are really important to revolutions. They get people going, they set dates and times, and they present an alternative ideology to get everybody else on board with it. There are people setting dates and times and locations, but there are so many, it’s a bit disorganized. The real issue is that it’s really easy to say what you’re against, but they haven’t really presented, systematically, an alternative.

For that reason, the great majority of the population, however sympathetic they may be, many Iranians are a little bit weary of what could come about after the regime falls. So they may be sympathetic, and there may be a fence sitter. They’re sitting on the fence, looking out, looking in from the outside, thinking about getting involved, but they don’t know what’s going to happen. So they haven’t really crossed that threshold yet. So having an organization that could present a viable, realistic, practical alternative is part of getting a big country like Iran, which is about 85 million people, getting them all on board.

Then the flip side of this is really important because while the movement is disorganized, the state is very organized. The state is very organized and very repressive. It has an entire repressive apparatus, not just in security forces, but in political prisons, in the judiciary, oftentimes rudimentary kangaroo court trials, torture, and rape. These are part of its repressive capacity, that’s actually very organized. Then there are the multi-layered security forces. So you see the ebbs and flows, and we’re at the point where it seems like the protests are evolving. There are more strikes than were happening initially, but the number of street gatherings has decreased, and the number of protests at universities is decreasing, but that doesn’t mean they’re not going to increase all of a sudden. So the uprising or the Iranian revolution itself was about 14-15 months long, with lots of ebbs and flows, and then basically a year into it is really when the majority of the population became mobilized.

The Shah fled the country January 16, 1979. December 10, 1978, towards the end of the revolution, was when the revolution was brought to a crescendo. So it’s kind of hard to predict what’s going to happen, but you see the state really employing maybe a fraction of its repressive capacity. Five hundred people are dead, probably more. We don’t know the exact number; it’s probably more. The state is able to repress much more than that. It is repressing. I don’t mean to downplay it or downsize it, but it’s just capable of much more than that. So that’s why I don’t really know what’s going to happen.

Another trend that I’m noticing is that the demonstrators are actually getting a little bit more organized than they were initially.

Talia Baroncelli

Right. Do you see a leader emerging at some point? You’ve spoken about how the protests currently are leaderless, and maybe that’s why some Iranians are a bit reticent to join onto this movement, or perhaps they are sympathetic towards the regime.

Pouya Alimagham

You’re going to get me killed because if I tell you that. As of now, there’s no viable leader, all the supporters of different leaders will probably come after me. There are plenty of leaders. The most well-known to Western audiences live in the West. There are many leaders in the country. A lot of them are in prison, and that’s kind of the issue. It’s difficult to have a viable leader spring from the country because of the repression.

History is our guide. [Ruhollah] Khomeini himself was the leader of the Iranian revolution. He was arrested and exiled, first to Turkey, then to Iraq. Fourteen years later, he returned from exile abroad and led a revolution. Fourteen years is a long time, but relatively speaking, it’s short. The problem I see is that a lot of the leaders that are presenting themselves as leaders in the West, they’ve been in the West for a lot longer than 14 years. There’s a big disconnect. Some of these leaders who have been in the West for this long are very closely tied to foreign governments, and that kind of hurts their political standing within the country.

The one constant in modern Iranian history is the desire to be independent. If you look at all the moments of revolutionary upheaval in the country, from the tobacco revolts to the 1890s, when the Qajar Shahs were just handing over the economy for short-term concessions or short-term gains. The economy was just being gifted away to foreigners, the British, and the Russians. Then there was this movement against the monarch to cancel the concessions that eventually led to a constitutional revolution to rein in the powers of these monarchs, so they don’t just give away the economy to foreigners, to imperial powers.

Then we go from the tobacco revolt to the constitutional revolution and then the nationalist movement of Mosaddegh, Mohammad Mosaddegh, who nationalized the Iranian oil company against British interests, and the British and Americans together ended up overthrowing him. So the constant is, and that brings us all the way to the Iranian revolution in ’78 and ’79, is to rest Iran’s independence, its sovereignty from foreign powers. So this is the constant that continues to this day. Can we have a leader, an alternative leader to this Islamic Republic, or to Khomeini coming in from abroad who is not tainted with its proximity to foreign governments?

That’s really the issue, in my opinion, of a lot of leadership in exile that’s presenting itself as alternatives, is that they don’t command that fealty that comes with being independent. Most of the leadership that came to power after the revolution actually ended up refusing a lot of foreign help.

The first president was Abolhassan Banisadr, and the Iraqis came to him. Saddam Hussein had a regional rivalry with the Shah. Saddam Hussein came, and his government approached Banisadr in exile and said, “Hey, we came to power through a military coup. How about we help you guys? Help you guys overthrow the Shah through a military coup?” Banisadr says, “Iran is different from Iraq, but also we can’t accept foreign help.” For that reason, he wasn’t tainted with being part of a foreign conspiracy or being an agent of a foreign government and was able to become the first president of the country. He was ultimately driven out by the conservative clergy in ’81. But he was the country’s first-ever president.

Talia Baroncelli

Right, and that’s obviously, or arguably a long-lasting gain and accomplishment of the revolution, is that it was able to accomplish this independence from Western imperialism. I wonder if the current regime actually feels threatened because Iranian propaganda is basically saying, “we’re being threatened by a Western-staged coup or uprising and we need to crack down on these protesters. We need to execute people so that we instill fear in the population so that they won’t protest.” Do you think that they actually are feeling really desperate at this point and are scared as to what is coming next?

Pouya Alimagham

I want to say this. First of all, every time there’s been an uprising against the Iranian government, the Iranian government presents it as being part of the Western conspiracy. Every single one of them. Part of that is because there have been conspiracies concocted against Iran. The most obvious example is when the U.S. and British overthrew the Iranian government in 1953, the democratically elected government of Mohammad Mosaddegh. That doesn’t mean that protesters today are part of this Western conspiracy. They have legitimate grievances, 100%, and they do their own cost-benefit analysis. They have their own agents, they have agency, and they’re protesting. The Iranian government likes to paint– it has to paint these people as part of a Western conspiracy to justify cracking down on them.

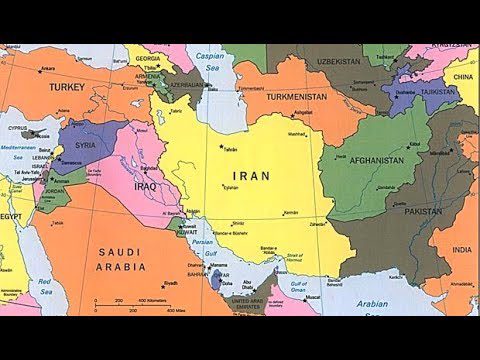

To be honest with you, the United States kind of makes it a little bit easy, not because it’s behind the protests, because in my opinion, it isn’t, but because of all the intervention at the hands of the United States in the region. Iran is essentially encircled by the United States. Before the Taliban came back to power, the United States had military forces in Afghanistan. It has military forces in Iraq, Syria, and the Persian Gulf. It is sanctioning Iran. The sanctions in Iran predate this uprising. It has nothing to do with it. It’s all about the nuclear program, which Iran was abiding by.

So there are all these really malicious policies that the United States is pursuing that give the Iranian government the justification to present or cast the demonstrators as being part of this Western conspiracy when they’re not. The protesters have nothing to do with– they’re not getting orders from the United States to rise up. They’re not these people who are doing the bidding of the U.S. government. They have their own beef with the Iranian government. They have every single incentive, personal reasons, or incentive to process the state. The state is very repressive, and it has been repressive and it’s only growing more repressive as it continuously loses its legitimacy. Its legitimacy has been chipped away at for years now.

In my book, I focused on the 2009 uprising because that was, and to this day still is, the biggest challenge to the Iranian government. People look at that as a failure because it was ultimately put down, but it had so many important victories, and its most important and lasting victory was that it shattered the state’s sources of legitimacy. It sees itself as having a monopoly on Islamic truth, on this history of the revolution. The uprising in 2009 robbed the state of all of these sources of legitimation and then, most importantly, kind of transitioned from “where is my vote” in June 2009 to December, “this month is a month of blood. Khomeini will be overthrown or toppled.” That was really the first public moment where demonstrators began to target the entire system– the core.

Every protest since 2009 has picked up where the Green Movement was put down. Every protest has been targeting the core ever since then. So one slogan you hear now in this uprising is ‘this year is the year of blood. Khomeini will be overthrown.’ So that’s why, as a historian, I like to talk about continuity. These things cascade, and they build on their predecessors. Even the green movement itself built on the symbolism and repertoire as a political action of the Iranian Revolution.

Talia Baroncelli

Right, so you see the current protesters coming out of that same trajectory in which the protesters of the green uprising were basically co-opting the symbols of the revolution to undercut the legitimacy of the Islamic Republic.

Pouya Alimagham

So they’re not doing that right now. My point in connecting these is that the Green Movement co-opted those symbols to attack the legitimacy of the Iranian government. Ever since 2009, it’s been operating without the same legitimacy it had before 2009. So every protest that’s happened since then has continued to chip away at that legitimacy. So today, they’re not really using a lot of the symbolism of the Iranian revolution because the whole thing with the Iranian government is that it has sources of legitimation. Its sources of legitimization come from Islam and the Iranian or Islamic Revolution. Then it institutionalized these symbols and the political, aesthetic, and educational landscape of the country. It shut down the schools, Islamized the curriculum, changed the books, and now the books talk about Khomeini as this great leader and Palestine. The Muslim cause of Palestine needing to be liberated. The political calendar changes. Now we have days like the seizure of the U.S. Embassy as a day of protest against U.S. imperialism. These are all days that came about through the revolution, that became institutionalized as part of the discourse or common sense, logic of the state post-revolution.

All of that was challenged in 2009. All of it was challenged. The one example I really like to give– there are two examples I really like to give, but I’ll focus on one so I don’t bore you. The Iranian government– that big demonstration I talked about earlier in our discussion, December 10, 1978, where literally millions of Iranians came out, that was Ashura. The anniversary of the martyrdom of the Prophet Muhammad’s grandson, Husayn [ibn Ali]. The whole idea was that this day of commemoration had typically been a day of mourning. You see, in the late ’60s and ’70s, across Shiite communities in the Muslim world, Husayn’s martyrdom became reinterpreted. If before you just mourned him as somebody that was oppressed and was killed in the 7th century, and if he died fighting tyranny, and if God let him die, the Prophet’s grandson died fighting tyranny, then our fate will be the same. There’s no point in resisting. That was like a very defeatist attitude.

What you end up seeing happening in the late ’60s and ’70s is saying “no.” The proper commemoration of Husayn’s martyrdom is to rise up against injustice; your life is not more important than his. If he was willing to fight and die, then who are you to say that you don’t want to do that? If you believe in him, then you should rise up against the tyranny and injustice of today because if Husayn was alive today, he’d be shoulder to shoulder with us. So you see that reinterpretation of Husayn’s legacy, and that’s why Ashura, December 7, 1978, was the biggest protest event in the history of the Iranian revolution. Anywhere between 10 to 15-17 million people, at a time when Iran’s population was about 34-35 million people, so almost half. That was the largest protest event in world history, at a time when the Shah had martial law imposed and a military government in power in Tehran.

Since the revolution, the Iranian government basically has co-opted Ashura now, saying that “we, as the Iranian government, support the David and Goliath struggle. We are the flag bearers of Husayn as we face down the United States in the region.” This is part of the history now of not just Islam but of the Iranian revolution. They drilled this lesson into the next generation that was raised under the authority of the Iranian government.

The Ashura of 2009 blows up in the face of the Iranian government because on Ashura, December 27, 2009, protesters are saying, “this month is a month of blood. Sayyid Ali Khamenei will be overthrown. This month is a month of blood. Yazid will be overthrown.” So now they’re acquitting the Iranian government with the murderers of Husayn on Ashura of all days. In doing so, they’re using the language of Islam and the Iranian Revolution against the so-called leader of the Iranian revolution. Khamenei, even though he was not the leader of the revolution, he embodies the continuity of the revolution. So one of his many titles is he is the leader of the revolution. This is when the government really considered the protesters as blasphemous. They are sacrilegious. They’re violating our sanctities. A lot of those death sentences that we see being handed down now, you really see them climax in the six-month uprising in the Green Movement. Six or seven-month uprising in the green movement, a lot of those death sentences were handed down in late December or early January because of those Ashura protests.

One last point. One of the really interesting things about 2009 is that by protesting the Iranian government on Ashura of all days, they brought to the fore a paradox that exists in Iran. Husayn, in the 7th century, died fighting power. He never achieved power. In the international arena, the United States is the world’s superpower, the sole superpower. For Iran, the Iranian government to be leading the charge against the United States in the Middle East could play on that Husayn-like-flag-bearing mantra of the David and Goliath struggle. The United States is the powerholder in the world, and here’s this resistant state fighting that David and Goliath struggle.

On Ashura 2009, the paradox comes to the fore because within the borders of Iran, domestically, the Iranian government claims Husayn’s mantle is the ultimate arbiter of power. The protesters were unarmed, facing down the state, and they were invoking Husayn’s legacy and facing down the state. That’s what I mean when I say they robbed the state of all these sources of legitimacy. The running government since 2009 has been a shell of its former self in terms of its sources of legitimation, and it has doubled down on repression. So it’s evolving and hardening its repressive capacity because it doesn’t have the legitimacy it once had before 2009. In the eyes of many, it never had legitimacy. If we’re speaking objectively, it was far more legitimate in 2009 than it is today because of everything that’s happened since.

Talia Baroncelli

Right, well, the regime must have been incredibly infuriated if it had been compared to Yazid. I mean, it’s like the ultimate sort of bad guy.

Pouya Alimagham

Absolutely.

Talia Baroncelli

So that’s probably why they didn’t take so well to that comparison. I think the green uprisings were also a slightly different context because the context of the uprisings was protesting the result of the [Mahmoud] Ahmadinejad election. How important was [Mir-Hossein] Mousavi, the other opposition candidate, in sort of fomenting protests and supporting the protests back then?

Pouya Alimagham

So he actually wasn’t that important. I often talk about the Green Movement when I talk about the protests today, and people don’t understand why I do that. As a historian of revolutionary movements, it’s actually really important to be able to compare and contrast. The protests in 2009 started about the election results, and then it evolved to be an anti-state, anti-Islamic Republic movement. As I said, they went from “where’s my vote” to “Khamenei’s rule is null and void, and he should be overthrown.” These are the slogans. The protest today started with the issue of the hijab and the death of one person, and it has evolved into something much bigger, has it not? And it evolved very quickly. So that’s why it’s important to see the continuity.

Mousavi’s people see him as a leader. He wasn’t. Of course, he was a candidate. He was a reformist candidate. What people ended up really doing was, before the elections, there were calls for boycotts. There were boycotts in 2005, which is why Ahmadinejad won resoundingly in 2005. There were calls for boycotts again in 2009. A lot of people didn’t want to boycott for two reasons. One is because the idea is that voting in the Islamic Republic is a fool’s errand because everything is kind of controlled. All the candidates are screened, and there’s a lot of truth to that, for sure. But for people who lived under four years of Ahmadinejad’s regime, they understood that when you vote, you don’t vote, and you get stuck with an IRGC [Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps] former commander who then appoints cabinet members, all or majority of his cabinet appointees were from the IRGC who had no experience in government. They were IRGC commanders and led to the securitization of the country more than ever before.

So when there were calls for boycotts in 2009, people were not excited about boycotting. They didn’t know what to do. They were kind of giving it a chance, and then they saw the television debates. So we had presidential debates in the country before, but this is the first time they were one-on-one. When they were one-on-one, Mousavi versus Ahmadinejad, even though there were four total candidates, the debates between Mousavi and Ahmadinejad were really intense. Mousavi was accusing Ahmadinejad of everything that a lot of Iranians have been saying amongst themselves, and now all of a sudden, they’re seeing it on national TV– about the corruption, the securitization of the state. Mousavi was like, “when you go on TV, and you talk about the Holocaust and stuff like that, you’re embarrassing us. You’re an embarrassment to us around the world. You’ve ruined the name of Iran across the globe.” What Mousavi had said resonated with people.

Then what ended up happening was a lot of activists used his campaign to mobilize against the government. So you hear, before election day, you were already hearing slogans in Tehran saying, “Marg bar Taliban. Che dar Kabul, che dar Tehran.” Death to the Taliban, whether in Kabul or in Tehran. Essentially equating clerical rule in Iran with one of its arch nemesis, the Taliban in Afghanistan. So you see that, and then when the election fraud happened, or Ahmadinejad’s supposed election win, you start seeing a massive protest movement that really had nothing to do with Mousavi. Mousavi wasn’t calling for it. A lot of times, when protests happened, he would jump on board with them after. He did show up in one important protest, but it was Monday, the Monday after. It was June 15. He shows up amongst the crowds, but whether he shows up or not, it was going to happen.

Then when the protest was driven underground after a week, it started resurfacing on specific days of action where the government was relaxing repression to get its supporters to come out, like the anniversary of the seizure of the U.S. Embassy. On those days, the Iranian government wanted people to come out, but to come out to protest with the government, not against it, with the government against the United States. On those days when repression was relaxed, green movement protesters re-emerged and reignited the protest movement. That had nothing to do with Mousavi in them. That strategy, that tactic, took Mousavi and them by surprise.

They’re doing stuff like that today. They’re calling for these days of action. That’s something that’s kind of part of Iranian culture. As I said, the Ashura of 1978 was the day of political action. When protesters died in the Iranian Revolution, their 40th day of mourning became not just a day where you go to the grave, but it became a day of protest. You saw that when Mahsa Amini’s 40th day came, people activated that culture, that ritual, for political reasons. That’s something that is kind of embedded in Iranian culture. In Iranian and Islamic cultures, there are these days, there are these cultural things that can or cannot be political. It depends on what you want to do with them. It’s kind of like this cultural reservoir where politically, you could activate them for political goals. That has nothing to do with Mousavi’s leadership or anything; that kind of is just part of Iranian history and culture.

Talia Baroncelli

So I wanted to speak about the political structure of the Islamic Republic because I think something that came out of the revolution was this sort of sprawling, interwoven, interlinked, massive government structure that relies– well, you have the Supreme Leader, and then the functioning of Khomeini and then followed by Khamenei was really dependent on the Revolutionary Guard, the IRGC, and then the paramilitary Basij. So I was wondering, do you think that you would need defections in all of these sort of institutions, all of these Iranian institutions, or if you have more defections in one, would that sort of be enough to overthrow the regime from within?

Pouya Alimagham

So, again, these are hard things to predict. I’ll say this: the Iranian government, for all of its failings, has created a system that’s almost coup-proof. It’s coup-proof to a certain extent. The Guardian Council vets presidential and parliamentary candidates, and it abuses that power, but it also just means that no U.S.-backed candidate or foreign-backed candidate could ever run for office. So it’s just one of those things where, as historians, when we look at the Shah’s government, we say that it’s a one-man show, a one-bullet solution. Whereas this is a system, the Iranian government has a very deep-rooted system of governance and repression. Whereas the Shah in 1978-79 had its secret police, its Imperial Guard, to protect the royal family and the army. It didn’t really have the means to put down demonstrators or demonstrations, so it dispatched the army to do it. That’s when we saw mass defections because these were soldiers, conscripts, who were conscripted into the army and trained in conventional warfare to defend the territorial integrity of the country from foreign invasions, specifically. Before the revolution, before the war, and before Saddam, Iraq was Iran’s regional rival.

So because it wasn’t prepared for the revolution, it used the soldiers to shoot demonstrators. A lot of them didn’t want to shoot not just their own countrymen and women but also maybe friends, neighbors, and family members because they were conscripts. So that’s why we saw so many defections. The Iranian government has learned this history, so it has created so many parallel security forces to prevent that.

The most obvious one, as you mentioned, is the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps, the IRGC. This is also why organization is really important. The order to create the IRGC came about before the Shah’s regime’s final collapse, and they had a discussion. Khomeini and Ayatollah Montazeri had a conversation about what we should do next. Montazeri, I think Montazeri and a couple of others suggested to Khomeini that “we can’t trust the Iranian military because the Iranian military has been built by the Shah and the United States. It’s loyal to the Shah. It has contacts with the United States. The same United States that overthrew Mosaddegh through a faction of the military. We can’t trust it. We need to not only purge the military, which includes my grandfather, who was a two-star General who had to flee the country, but the idea was that we have to not only purge the military, but we have to create an entirely parallel military force whose main purpose is to guard the revolution.” That’s why it’s called the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps, and by that, he means to protect the state and its leaders. Khomeini gave that order to create the IRGC when the Shah’s military was in power. This is why organization is so important. The state has been preparing for this, for all of its failings.

I remember, I think, weeks into COVID, the IRGC had this really silly show in the country somewhere in Iran, and it proclaimed that it had found the vaccine to COVID way before there was a vaccine anywhere else, and that turned out to be BS. For all the failings like that, it’s so prepared to put down demonstrators and also fight wars abroad. That’s the one thing it has mastered. So, historians, we call Iran a guerrilla state, and then the flip side to that is we call Israel a garrison state. These are two regional rivals now. Israel has walls everywhere, checkpoints everywhere, and barbed wire everywhere. Iran has tunnels and multiple layers of security forces and military forces. It has allied armed groups that it created or co-founded across the region, from Hezbollah in Lebanon, through the Al-Hashd al-Sha’bi forces in Iraq and elsewhere.

To answer your question, it’s very hard for me to imagine a scenario. It’s not impossible, but it’s hard for me to imagine a scenario where there will be a military coup or defections. I think a civil war is more likely in comparison to that scenario, but I still don’t know if civil war is likely.

Talia Baroncelli

You speak about the Islamic Republic as stylizing itself, as being a resistant state, as helping resistance abroad, so in Palestine, for example. What is the role of the IRGC in trying to enact that support for resistance as well as the role of Basij? So I guess the Basij was probably formed in the Iran-Iraq War.

Pouya Alimagham

Yes. I think the most important case study for the IRGC as it relates to its military efforts, vis-à-vis Israel and the Palestinians, is Hezbollah and Lebanon. People often call it a proxy of the Iranian government. I don’t like to use that language because people have agency. So Hezbollah, its ultimate leader, is Khomeini for certain.

So if you look at this brochure or this pamphlet that came out in 1985, it’s in Arabic; when they proclaimed the existence of the organization in 1985, it was formed in ’82, but they came out of the shadows in ’85 with the publishing of this leaflet. They have the picture of it– Hezbollah martyrs. Then on the back of it is a picture of Khomeini. They say in the leaflet that “as Muslims, what fate befalls Muslims in Afghanistan or the Philippines, barely affects the body of the Islamic nation of which we are an integral part per the leadership of our guardian jurist Ayatollah Khomeini.” The interesting thing about Hezbollah’s creation is that it has a lot of factors that kind of aggregated together to spark its creation. It all happens in ’82.

In 1982, after two years of war with Iraq, Iran liberated Khorramshahr and basically was really emboldened. After two years of being on the defensive, it is now on the march. Right after Khorramshahr is liberated, Israel invaded Lebanon. So Iran is feeling so emboldened that now it’s also not only looking at Iraq and preparing a counter-invasion of Iraq for the first time, but it’s looking beyond Iraq, beyond the border war, and looking across the region. When Israel invades Lebanon to fight the PLO, a lot of Lebanese Shiites get caught in the crossfire, and ruptures exist within the existing Shiite organizations.

Amal, at the time, was an organization that predates the Iranian Revolution and predates the Islamic Republic. Because some Shiites were critical of the Palestinian armed presence in their areas, especially in south Lebanon, some Shiites welcomed the Israeli invasion. The fact that some Shiites welcomed the Israeli invasion angered those other Shiites. Those other Shiites met with Khomeini in ’82, right when Khorramshahr was liberated, and then Israel invaded Lebanon. Iran has this conference, a conference of the world’s dispossessed Mostaz’afan. Khomeini meets in private with a delegation of radical Lebanese Shiite clergymen and basically says, “go back and turn your mosques into centers of jihad and we will be there and with you every step of the way to help you push back this invasion.” And then Khomeini dispatches 1,500 guardsmen, IRGC guardsmen, to go through Syria into the Beqaa Valley and basically start training Hezbollah fighters.

So people often say that it’s Iran’s proxy, but Iran was obviously huge in the creation of Hezbollah. There were also Lebanese clergymen who, because of the Israeli invasion, basically issued a call to arms and many people signed up to fight the Israeli invaders.

Another example is when the uprising happened in Syria in 2011, and onwards, Hezbollah got involved with that. People say this is evidence of Hezbollah being Iran’s proxy because Iran is so close to the Syrian government and didn’t want to see the Syrian government fall. It ordered Hezbollah to get involved and basically do Iran’s bidding in Syria. That’s an oversimplification because the opposition to the Syrian government declared that as soon as they win the war and come to power, they’re going to shut off Iranian support to Hezbollah. As soon as Hezbollah heard that, they’re like, “well, then we got to make sure you don’t come to power so that we keep the arms flowing to us.” So they had their own incentive, especially since so much of the rebellion in Syria was fiercely anti-Shiite Takfiri groups. They didn’t want a much bigger country like Syria that essentially enveloped Lebanon to have Takfiri rebels in power. So Hezbollah helped turn the tide. Hezbollah, the Iranian government, and the Russians helped turn the tide in favour of the Syrian government. That’s really part of Iran’s regional influence, its relationship with Hezbollah. I would not call it a proxy, but Iran was very important to its founding, and it is very important to Hezbollah’s strength and sustainment, for sure.

Talia Baroncelli

Right, well, you’ve spoken about the regional ecosystem in the Middle East; what about the dual functionality of the Basij that came about out of the Iran-Iraq War? The Basij as being a paramilitary group that could crack down on peaceful protests within the country but also presented itself as being capable of fighting imperialism.

Pouya Alimagham

Yeah, so if we’re going to talk about the Iran-Iraq War and the emergence of the Basij, and what they’re doing now in terms of fighting imperialism, but then also cracking heads in the country, we got to first mention the war.

I think it was this famous sociologist, Charles Tilly, that said, “war builds states,” and the Iran-Iraq War became the impetus to create the state and, more importantly, its narrative. This is the era of the IRGC and the Basij. The Basij was created as this fierce Shiite force that was fighting the Yazid of the time, which was Saddam Hussein and its backers, the Soviet Union, West Germans, the French, the British, the Americans, and a lot of Arab heads of state. When you go to Iran today, you see all these murals dedicated to the martyrs of the war. So that memory is part of the aesthetic landscape of the country. A lot of Basij fighters, a lot of Basij paramilitary force members today, they see themselves as carrying on that legacy.

Now, the interesting thing is that there is a big difference between the younger Basij people, Basij members, and then the older ones. The older ones who fought in that war were very zealous, a lot of them are like fathers now, and they have daughters. They may not be excited about some of these anti-women ordinances from the state that they helped protect, helped establish, and defend.

The younger Basij forces– and I’m generalizing, not all the younger Basij forces are like this, but a lot of the younger Basij forces looked to the older ones both with respect and admiration for having fought in the Iran-Iraq War. Also, some of them say that the generation has gotten soft and they got old. So there is this new generation of young zealots, and they see themselves as carrying forth the banner of that resistance to the Iraqi invaders now resisting to the United States. Many of them see going up against these protesters as part of the anti-imperialist struggle because they have bought into the government narrative that the protesters are part of that Western conspiracy.

There’s a really good book on part of what we’re talking about right now, about the differences in the older and younger Basij generations. It’s a book by Narges Bajoghli. It’s called Iran Reframed. I couldn’t put it down. I read it in one day. It’s short, but it’s a great book. I loved it. It’s very illuminating, for certain. We tend to look at these things as monoliths and this narrative. Her book complicates that narrative and shows you that there’s a generational divide within not just the state but its security forces.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, the Iran-Iraq War clearly played a really important role in post-revolutionary Iranian identity. Now that we’re talking about history, what about before the revolution? So under the Shah, Iran is basically a one-man monarchy. What were the social structures, class formation, and different political structures which enabled the revolution? In particular, how the Shah emboldened the clerics rather to sort of maybe tame down or dampen down the threat of communists in the country, and in doing so, actually brought about the revolution.

Pouya Alimagham

So I’m smiling because I love the question. This is essentially– what were the causes of the Iranian revolution? That’s essentially what you’re asking. There’s an entire literature on this. I can’t give you an example. I can only try to give you the contours of the debate and probably what I think as well.

The Shah, for certain, was part of the American camp in the Cold War. He was fiercely anti-communist and was dispatching Iranian soldiers to places like Oman to help put down Marxist rebellions in places like Dhofar Oman. He was the guardian of the Persian Gulf, the guardian of Western interests in the Persian Gulf. He dispatched this guy named Imam Musa Al-Sadr to Lebanon because Shiites, typically when they were minorities before the Iranian revolution, they’re typically the poorest and the most marginalized. So for that reason, in the Cold War, Marxism appealed to them probably the most because it spoke to their economic plight. The Shah sees a lot of the Shiites in places like Najaf and Karbala in Iraq, the shrine cities, and the Shi’i shrine cities of Najaf and Karbala. He sees Shiites in places like Lebanon gravitating towards Marxism, and he sees that as a domino effect in the largest Shiite-majority country in the world being Iran, and he was worried that might impact Iran. So he sends someone like Imam Musa Al-Sadr to preach religion and to basically guide Lebanese Shiites away from Marxism and towards religion.

Domestically, the Shah was cultivating Shiism, but not the way you think. People mostly blame the Shah for the revolution in the sense that he cultivated the clergy, and then they rose up against him. That’s not the entire picture. By that, I mean most of the clergy that came to power or many of the clergy that came to power after the revolution were either at one point in prison, tortured, or exiled. So the clergy was not given a total free hand to preach religion and then mobilize against the state.

Khomeini was arrested, and he was exiled for 14 years. Khomeini’s one-time successor, Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri, was imprisoned for many years, he was tortured, and then he was made to listen to the torture of his son, Mohammad Montazeri. Ayatollah Taleghani, the first Friday prayer leader after the revolution, was tortured extensively in the ’70s to the point that when he died soon after the revolution. Some believed he died because the more militant clergy that wanted an Islamic Republic poisoned him. That’s one of the conspiracy theories because Taleghani was a clergyman, but he was not down with the clerical-led government. He was not supportive of it whatsoever. Some believe he was poisoned by those who wanted to create a clerical-led government. Some people argued that the torture he sustained took a toll on him, and essentially, he took his life when he got a little bit older.

Then there’s Ayatollah Ghaffari, who was a clergyman who died in prison through torture. So it’s not one of those things where he cultivated Islam. It’s not the whole story. It’s part of the story that the Shah built mosques to get people to be more religious, not because he wanted religion. He was personally pretty– he had moments of piety. He survived an assassination attempt when he was young, and he thought God intervened to save his life. He had that kind of worldview, but he had a secular policy. His politics were secular. When you talk about the social forces, it was a militant faction of the clergy that essentially forced the entire nationwide mosque network to go into format revolution. It was partially them and then an alliance with the bazaar class, the merchant class, because Iran in the mid-70s underwent a severe recession. When inflation occurred, the state blamed the merchant class and began to fine them. When they protested those fines, they were arrested.

Talia Baroncelli

Sorry. I have a question. When you’re talking about inflation, are you talking about inflation following the 1973 oil prices?

Pouya Alimagham

No. Yeah, actually, I thought you were going to say following the revolution.

Talia Baroncelli

No. Following the oil prices when the Shah basically increased the price of oil by 14%.

Pouya Alimagham

Yeah. So what ends up happening is the Shah goes on a spending spree. His regime was awash with billions in oil wealth because of the Arab embargo following the Yom Kippur War of 1973. Then he went on this spending spree, but the country’s infrastructure was not ready. You can’t import all these things when your ports are not built, when you don’t have the roads and the transportation systems to bring in all those. So there was a bottleneck in Iran’s ports that caused recession and inflation. The merchant class was blamed for it. When the prices skyrocketed, they were fined. When they protested those fines, they were arrested. So the merchant class became incentivized to side with the enemies of the regime, and that’s essentially the militant fashion of the clergy. The merchant class also has been historically close with the clergy– a lot of intermarrying, the tobacco revolts, the constitutional revolution, a lot of it has to do with them joining forces against the monarchies, against the monarchs.

The student class was very supportive of the Iranian revolution. A lot of them were Marxists or leftists. They saw the Shah as the imperialist outpost in the country, and they saw Iran as being part of the capitalist West, but in a way that was benefiting the metropoles of the colonial powers. They had the incentive to help bring him down.

There’s one other thing I wanted to say. We’re talking about the political situation, so the Shah situation. The Shah was growing. Because of the oil wealth, he thought– and this is kind of what we call in academia the oil curse. He felt that because he wasn’t taxing the population, he didn’t have to give them representation. So in 1975, I believe, he scrapped the two-party system in favour of the one-party system. In a way, it was kind of like a fascist system. The two-party system itself was what we call in history the yes and the yes sir parties. They were like rubber stamps of the Shah anyways. And even that rubber stamp was consolidated into one-party system.

So you had Iranians going to universities. The universities, a lot of them, that the Pahlavi dynasty had established. So they’re learning these new ideas about democratic government, anti-imperialism, nationalism, independence, all these things that they’ve been learning about for 100 years, but now the masses are learning it in education systems in the country. Then they see that the economy is modernizing. So you see the emergence of a modern middle class. Typically the modern middle class are the ones that can be activists. Typically, if you’re super poor, people think revolutions happen by the lower class. In 1978-79, that was not the case. The poor are too busy, typically struggling to survive for their daily bread. They don’t have refrigerators, let alone food in the refrigerator. They don’t have any of that. So if they go on strike or if they’re protesting, that means they’re not getting their wage for that day to be able to put food on the sofre; if you want to call it a table, sure.

The rich typically don’t want to see changes because the status quo benefits them. So really, the emergence of a modern middle class in the country and modern ideas, you see them wanting to agitate for political openness and participation and inclusion, and then the state was going in the opposite direction by narrowing the avenues for political participation, by scrapping a two-party system. So you see the whole generation saying, “if we can’t participate within the system, then the entire system has to go. But participate by casting a referendum against the state, by voting with our feet in mass protest,” which is essentially what happened.

Talia Baroncelli

At that point, it was quite apparent that the monarchy was extremely repressive. I mean, SAVAK, the secret services, was torturing political prisoners. I think something like a thousand political prisoners was killed towards the end of the ’70s, before the start of the revolution, which is maybe something a lot of Iranians in the diaspora don’t always want to recognize when they speak about the Shah and when they still continue to support their nostalgic idea of what the monarchy was.

Pouya Alimagham

Yeah, and I grew up in the diaspora, so I’m very well attuned to these arguments that I hear, and I’ve been hearing all my life. When you talk about the abuses of the Shah, there are two typical responses. One, they say, is that “the Shah didn’t know about it. His secret police were doing it, and they kept it from him,” which is complete BS. Another one is that “okay, fine, he was repressive, but he’s nothing compared to today’s government,” and that’s actually true, but that is not an excuse. That does not justify anything. The Iranian government today is far more repressive than the Shah ever was, but that does not give the Shah a get-out-of-jail-free card. Like, there’s a reason why the revolution happened. There are structural, ideological, and repressive reasons for why it happened. Again, it’s because people want to participate in the political system. The repression and the consolidation of the two-party system into one made people realize that they couldn’t participate. The only real way to participate is by their feet and overthrowing the entire system. The Iranians are reaching that point today, too, by the way.

Talia Baroncelli

Speaking about today, let’s bring this full circle. What do you think– I mean, this is a really difficult question to answer, but what should countries be doing and not be doing to support the protesters?

Pouya Alimagham

These are all sensitive questions. So I’ll tell you what people are saying, and I’ll tell you what I think. Some people are saying that “this is the moment. The time has come. Everyone should be doing everything they can to isolate the Iranian government and help facilitate its demise at the hands of the people and those demonstrating.” So I understand that point. My issue then is, as a historian of the whole region and U.S. foreign policy as well, I live in the United States. What we’re really talking about, for me at least, is what should the U.S. government do? When I know the history of the United States’ involvement in the Middle East, when I know the history of the United States’ involvement in Iran and subverting democratic movements around the world and democratic governments, I think that it’s a matter of legitimacy. The United States does not have legitimacy, even though it sees itself as the oldest and the greatest democracy in the world. I understand how Americans like to see themselves. It does not correspond with the reality of Europe’s foreign policy everywhere else outside of Eastern Europe post-Cold War.

I think if the U.S. government wants to preach and pontificate, I would hope that it would do so consistently because that’s when U.S. rhetoric about freedom carries weight, is when it’s doing it consistently. It’s difficult to support the freedom of Iranian protesters while you’re enabling the occupation of the Palestinians or when you’re sustaining one of the most retrograde governments in the world, the Saudi government. Like Trump himself said it. “The moment we withdraw our security guarantee from these countries in the Persian Gulf region, they’ll fall within a week.” There’s a bit of truth to that. Trump admitted that the U.S. arms sustain dictatorships in the Persian Gulf region. So I think that if the United States wants to do something in support of the Iranian government, it needs to be consistent about advocating for freedom and living up to its own ideals, so that when it does say something, it doesn’t end up being to the detriment of the movement where the Iranian government says, “look, the United States is saying this. It must be behind the protest movement.” That’s the historian’s answer or a historian’s answer.

Talia Baroncelli

Then according to that, they should also roll back certain sanctions which continue to immiserate the population. I mean, you’ve already said that the protests are not a result of the sanctions. I mean, Mahsa Amini was not killed because of the sanctions, but they still played a role in creating these very specific socioeconomic conditions and fleecing the Iranian–

Pouya Alimagham

Yeah, it’s crazy because the discourse is narrowed. It’s very difficult to talk about the sanctions. The sanctions before this uprising, and to this day, don’t have credibility. The sanctions were about the nuclear program. Iran more or less surrendered its nuclear program. It had been abiding by the JCPOA. The U.S. arbitrarily subverted the JCPOA and sanctioned the country. For a full year, Iran continued to abide by the JCPOA until they basically stopped. To this day, it’s clambering to return to the JCPOA. The strategy really is this, and they’ll tell it to you themselves; the very hawkish Iranians in the diaspora will tell you this themselves. They’re like, “we don’t want…” First of all, they’ll tell you two things, “that the sanctions target the government only,” and that is just not true. The sanctions are on the financial sector. That financial sector is for the whole country. So there are charts– you can look at the charts– the moment the sanctions were snapped back by the Trump administration, inflation that was up here, spiraled out of control. That inflation affects the whole country. So if you’re 65 years old or 60 years old, you’re preparing to retire and now your savings is not worth the paper it’s on, that has to do with the sanctions. People don’t want to talk about it.

Let’s be honest about it. Now, why are the sanctions happening? They will tell it to you themselves. The Iranians in the diaspora, the Saudi government, the Emirati government, and the Israeli government don’t want an economic solution to Iranian suffering. They want a political solution. The Iranian government does not want a political solution. It wants an economic solution. It wants to be able to invest and trade and then improve the standards of living for the population in hopes that they’ll just acquiesce to the status quo, essentially like the Saudis and the Chinese citizens. All these people that are against sanctions want to keep the Iranians at a certain below-sustenance level, so they could be even more angry about the politics of the day, so they could seek a political solution.

The interesting thing is that the Israelis want a political solution for Iran and not an economic solution; when it comes to Palestinians, they want an economic solution and not a political one. So they don’t want a two states negotiated settlement with the Palestinians or any kind of settlement with the Palestinians. They’re just like, “look, we want to continue the occupation, we want to continue building in Palestinian lands, but let’s bring in some investment, let’s improve their lives, so they just shut up. Maybe their quality of life will be better, and then they don’t want to jeopardize that.” So it’s a little bit dishonest to talk about Iranian suffering and not talk about sanctions. Sanctions are a big part of the story.

But again, just like you said, the sanctions don’t explain the fact that we have a supreme leader for life in the country. It doesn’t explain the fact that we have a morality police. It doesn’t explain the fact that we have torture and rape in prisons for both men and women. It doesn’t explain the fact that somebody was ruled by dumb laws like the Hijab law, and then she died under custody. The sanctions don’t excuse any of that. But we have to understand the sanctions are part of the story.

Talia Baroncelli

Definitely, well, Pouya, thank you so much for that deep historical dive and for your analysis of the current protests. It would be great to have you on another time.

Pouya Alimagham

It was my pleasure. Thank you for the wonderful questions.

Talia Baroncelli

Thanks for joining me, Pouya. Take care. Bye.

Talia Baroncelli

Hola, soy Talia Baroncelli y están viendo theAnalysis.news.

En breve me acompañará Pouya Alimagham para hablar de las protestas en Irán, así como de la historia anterior a ellas.

Pero primero, no olvide visitar nuestro sitio web, theAnalysis.news, y hacer clic en el botón de donar y suscribirse a nuestro boletín.

Regreso en un momento.

Estoy muy emocionada de que me acompañe Pouya Alimagham. Es historiador y conferencista sobre el Oriente Próximo moderno en el MIT, y también es el autor del libro Contesting the Iranian Revolution: the Green Uprisings.

Muchas gracias por acompañarme, Pouya.

Pouya Alimagham

Encantado de estar aquí. Gracias.

Talia Baroncelli

Quería preguntarte sobre las protestas actuales. En este momento llevamos unos tres meses de protestas. Han pasado tres meses desde que Mahsa Amini fue asesinada por la policía moral. Más de 100… o en realidad casi 500 personas han muerto durante las protestas. Y hemos visto a dos personas ejecutadas.

Así que me preguntaba si crees que las protestas seguirán teniendo impulso o si las aplastarán.

Pouya Alimagham

Es una buena pregunta.

El impulso no necesariamente tiene que ser todos los días. El levantamiento en realidad ha cumplido el día 96. Tiene muchos flujos y reflujos. Cada viernes se da un gran pico, especialmente en lugares como Zahedan, donde se reúnen para la oración del viernes y luego protestan, sobre todo los baluchis.

Pero la represión es real. Cuando tienes un movimiento desorganizado… Y cuando digo desorganizado, no estoy tratando de criticarlo. No estoy tratando de decir que es ineficaz o que no hay organización. Pero las organizaciones son realmente importantes para las revoluciones. Hacen que la gente se ponga en marcha, fijan fechas y horas, presentan una ideología alternativa a la que puede adherirse la gente.

Hay gente que pone fechas y horas y lugares, pero hay muchos que están un poco desorganizados. Y el problema real es que, debido a que realmente no han presentado… Es muy fácil decir contra qué estás, pero en realidad no han presentado sistemáticamente una alternativa. Y por eso, la gran mayoría de la población, aunque lo apoyen, muchos iraníes sienten algo de recelo de lo que podría pasar después de la caída del régimen. Es posible que lo apoyen, es posible que estén indecisos. Están mirando desde fuera, pensando en involucrarse, pero no saben lo que va a pasar. Así que realmente no han cruzado ese umbral todavía.

Entonces, tener una organización que pueda presentar una estrategia viable, realista y práctica es importante para lograr convencer a toda la población en un país grande como Irán, que tiene alrededor de 85 millones de personas. Y luego, la otra cara de esto es realmente importante porque, aunque el movimiento está desorganizado, el Estado está muy organizado. El Estado está muy organizado y es muy represivo. Posee todo un aparato represivo, no solo en las fuerzas de seguridad, sino en las cárceles políticas, en el poder judicial, a menudo juicios falsos sumarios, tortura, violación. Estos son parte de su capacidad represiva. Es realmente muy organizado. Y luego están las diferentes capas de las fuerzas de seguridad.

Entonces, ves los flujos y reflujos, y estamos en ese punto donde parece que las protestas están evolucionando. Hay más huelgas que al principio, pero el número de protestas en las calles ha disminuido. El número de protestas en las universidades está disminuyendo, pero eso tampoco significa que no vayan a aumentar de repente. La revolución iraní en sí duró aproximadamente 14-15 meses, muchos flujos y reflujos. Y luego, básicamente, un año después es realmente cuando la mayoría de la población se movilizó. El sah huyó del país el 16 de enero de 1979. El 10 de diciembre de 1978, hacia el final de la revolución, fue cuando la revolución entró en un crescendo.

Es un poco difícil predecir lo que va a pasar. Pero ves que el Estado realmente emplea quizá una pequeña fracción de su capacidad represiva. Quinientas personas han muerto, probablemente más. No sabemos el número exacto. Probablemente sea más. Pero el Estado es capaz de reprimir mucho más que eso. Entonces, es represión, no pretendo restarle importancia o reducirlo, pero es capaz de mucho más que eso. Es por eso que realmente no sé lo que va a pasar.

Otra tendencia que estoy notando es que los manifestantes están algo más organizados de lo que estaban inicialmente.

Talia Baroncelli

¿Y ves surgir un líder en algún momento? Porque has hablado de que las protestas actualmente no tienen líderes, y quizá por eso algunos iraníes son un poco reticentes a unirse a este movimiento, o quizá simpatizan con el régimen.

Pouya Alimagham

Vas a hacer que me maten, porque si te digo que en este momento no hay líder viable, todos los partidarios de diferentes líderes probablemente vendrán a por mí.

Hay un montón de líderes. Los más conocidos para el público occidental viven en occidente. Hay muchos líderes en el país. Muchos de ellos están en prisión. Y ese es parte del problema. Es difícil que salga un líder viable del país debido a la represión. Pero la historia es nuestra guía. El propio Jomeini fue el líder de la revolución iraní. Fue arrestado, exiliado primero a Turquía, luego, a Irak. Catorce años después, regresó del exilio en el extranjero y lideró una revolución. Catorce años es mucho tiempo, pero relativamente hablando, es corto.

El problema que veo es que muchos de los líderes, los que se presentan como líderes en occidente, han vivido en occidente mucho más de 14 años. Entonces, hay una gran desconexión. Y algunos de estos líderes que han estado en occidente durante tanto tiempo están muy vinculados a Gobiernos extranjeros, y eso daña su posición política dentro del país.

Así que es como… La única constante en la historia iraní moderna es el deseo de ser independiente. Si vemos todos los momentos de agitación revolucionaria en el país, las revueltas del tabaco de la década de 1890, donde los sahs Qājār simplemente estaban entregando la economía a cambio de concesiones a corto plazo o ganancias a corto plazo, estaban regalando la economía a los extranjeros, los británicos y los rusos. Luego, surgió este movimiento contra el monarca para cancelar las concesiones, que eventualmente conduce a una revolución constitucional para controlar los poderes de estos monarcas para que no entregaran la economía a los extranjeros, a las potencias imperiales.

Luego, pasamos de la revuelta del tabaco a la revolución constitucional y luego el movimiento nacionalista del doctor Mohammad Mosaddegh, que nacionalizó la compañía petrolera iraní, contra los intereses británicos, y los británicos y los estadounidenses juntos terminaron por destituirlo. Así que la constante, y esto nos lleva hasta la revolución iraní en el 78-79, es arrebatar la independencia y soberanía de Irán en manos de las potencias extranjeras. Esta es la constante que continúa hasta el día de hoy. ¿Podemos tener un líder, un líder alternativo, a esta República Islámica, a Jamenei, que venga del extranjero y que no esté contaminado por su proximidad a los Gobiernos extranjeros? Y ese es realmente el problema, en mi opinión, de muchos líderes en el exilio que se presentan como alternativas, que carecen de esa lealtad que viene con ser independiente.

La mayoría de los líderes que llegaron al poder después de la Revolución terminaron rechazando gran parte de la ayuda extranjera. El primer presidente fue [Seyyed] Abolhassan Banisadr, y los iraquíes acudieron a él… Saddam Hussein tenía esta rivalidad regional con el sah. Llegó Saddam Hussein, su Gobierno se acercó a Banisadr en el exilio y dijo: “Llegamos al poder a través de un golpe militar. ¿Qué les parece si los ayudamos a derrocar al sah mediante un golpe militar?”. Y Banisadr dice: “Irán es diferente de Irak, pero tampoco podemos aceptar ayuda extranjera”. Y al no estar contaminado por ser parte de una conspiración extranjera o ser agente de un Gobierno extranjero, pudo convertirse en el primer presidente del país. Finalmente, fue expulsado por el clero conservador en el 81. Pero él fue el primer presidente del país.

Talia Baroncelli

Sí. Y eso es obviamente, o podría decirse, una conquista duradera y un logro de la revolución, que fue capaz de lograr esta independencia del imperialismo occidental. Entonces, me pregunto si el régimen actual realmente se siente amenazado. Porque la propaganda iraní básicamente dice: “Estamos siendo amenazados por un golpe o levantamiento organizado por occidente y tenemos que tomar medidas enérgicas contra estos manifestantes, debemos ejecutar a la gente para infundir miedo en la población para que no proteste”. ¿Crees que realmente se sienten desesperados en este momento y tienen miedo de lo que viene después?

Pouya Alimagham

Quiero decir esto. En primer lugar, cada vez que ha habido un levantamiento contra el Gobierno iraní, el Gobierno iraní lo presenta como parte de la conspiración occidental. Siempre es así. Pero parte de eso se debe a que se han organizado conspiraciones contra Irán. Y el ejemplo más obvio es el derrocamiento del Gobierno iraní por parte de los británicos y estadounidenses en 1953, el Gobierno elegido democráticamente del doctor Mohammad Mosaddegh.

Eso no significa que las protestas de hoy sean parte de esta conspiración occidental. Sus reivindicaciones son 100 % legítimas. Y hacen su propio análisis de costo-beneficio, tienen agencia y están protestando. Pero al Gobierno iraní le gusta pintar, tiene que pintar, a esta gente como parte de una conspiración occidental para justificar su represión.

Y, sinceramente, Estados Unidos se lo pone bastante fácil. No porque esté detrás de las protestas, porque en mi opinión no lo está, sino por toda la intervención de Estados Unidos en la región. Irán está esencialmente rodeado por Estados Unidos. Antes de que los talibanes volvieran al poder, Estados Unidos tenía fuerzas militares en Afganistán. Tiene fuerzas militares en Irak, Siria, el Golfo Pérsico. Tienen sanciones contra Irán. Las sanciones en Irán son anteriores a este levantamiento, no tiene nada que ver con eso. Se trata del programa nuclear, que Irán estaba cumpliendo.

Entonces, Estados Unidos está aplicando todas estas políticas deletéreas que le dan al Gobierno iraní la justificación para presentar o tildar a los manifestantes como parte de esta conspiración occidental, cuando no lo son. Los manifestantes no tienen nada que ver con eso. No están recibiendo órdenes de los Estados Unidos para rebelarse. No obedecen al Gobierno de los Estados Unidos. Tienen sus propios problemas con el Gobierno iraní. Tienen todos los incentivos, razones personales o incentivos, para protestar contra el Estado. El Estado es muy represivo y ha sido represivo y se está volviendo más represivo a medida que pierde su legitimidad. Y su legitimidad se ha visto minada durante años.

En mi libro, me concentro en el levantamiento de 2009 porque ese fue, y hasta el día de hoy sigue siendo, el mayor desafío al Gobierno iraní. Y la gente lo ve como un fracaso porque al final fue sofocado, pero tuvo muchas victorias importantes, y su victoria más importante y duradera fue que destruyó las bases de legitimidad del Estado. El Estado se ve a sí mismo como poseedor del monopolio de la verdad Islámica, sobre esta historia de la revolución. El levantamiento de 2009 le robó al Estado todas estas bases de legitimidad y luego, lo más importante, pasó de “¿Dónde está mi voto?” en junio de 2009 a, en diciembre: “Este mes es un mes de sangre. Jamenei será depuesto o derrocado”. Y ese fue realmente el primer momento público en el que los manifestantes comenzaron a atacar todo el sistema, el núcleo.

Cada protesta desde 2009 ha continuado donde el Movimiento Verde fue aplastado, y cada protesta ha tenido como objetivo el núcleo desde entonces. Así que un eslogan que escuchas ahora en este levantamiento es: “Este año es el año de la sangre. Jamenei será derrocado”. Por eso, como historiador, me gusta hablar de continuidad. Estas cosas emanan de las anteriores y se suman a ellas. Incluso el propio Movimiento Verde se sumó al simbolismo y el repertorio y la acción política de la revolución iraní.

Talia Baroncelli

Entonces, ¿crees que los manifestantes actuales siguen esa misma trayectoria en la que los manifestantes del Levantamiento Verde básicamente se apropiaron de los símbolos de la revolución para socavar la legitimidad de la República Islámica?

Pouya Alimagham

No están haciendo eso ahora. Pero mi intención al conectarlos es que el Movimiento Verde se apropió de esos símbolos para atacar la legitimidad del Gobierno iraní. Desde 2009, ha estado operando sin la misma legitimidad que tenía antes de 2009. Entonces, cada protesta que ha ocurrido desde entonces ha seguido erosionando esa legitimidad. Así que hoy en día no están usando mucho el simbolismo de la revolución iraní.

Todo el asunto con el Gobierno iraní es que sus bases de legitimidad provienen del islam y de la revolución iraní, o Islámica. Y luego institucionalizó todos estos símbolos, y el panorama político, estético y educativo del país. Cerraron las escuelas, islamizaron el currículo, cambiaron los libros, los libros hablan ahora de Jamenei como este gran líder, y la causa musulmana de Palestina, que debe ser liberada. Y el calendario político cambia. El día de la toma de la embajada de EE. UU. es un día de protestas contra el imperialismo de EE. UU. Estos son todos los días que surgieron a través de la revolución, que se institucionalizaron como parte del discurso o lógica de sentido común del Estado después de la revolución.

Todo eso fue cuestionado en 2009. Todo eso fue cuestionado. El ejemplo que realmente me gusta dar, hay dos ejemplos que me gusta mucho dar, pero me enfocaré en uno para no aburrirte, es que el Gobierno iraní… Esa gran manifestación de la que he hablado antes en nuestra discusión, el 10 de diciembre de 1978, donde salieron millones de iraníes, eso fue Ashura. El día del aniversario del martirio del nieto del profeta Mahoma, Hussein, el imán Hussein.

La idea general era que… Este día de conmemoración había sido típicamente un día de luto. A finales de los años 60 y 70, en las comunidades chiitas del mundo musulmán, el martirio de Hussein se reinterpreta. Antes lo lloraban como alguien que fue oprimido y asesinado en el siglo VII, y si murió luchando contra la tiranía, y si Dios lo dejó morir, el nieto del Profeta murió luchando contra la tiranía, entonces nuestro destino será el mismo. No tiene sentido resistirse. Esa era una actitud muy derrotista. Lo que sucede a finales de los años 60 y 70 es que dicen: “No. La conmemoración adecuada del martirio de Hossein es levantarse contra la injusticia. Tu vida no es más importante que la de él. Si él estaba dispuesto a luchar y morir, entonces, quién eres tú para decir que no quieres hacerlo? Si crees en él, debes rebelarte contra la tiranía y la injusticia de hoy. Porque si Hussein estuviera vivo hoy, estaría hombro con hombro con nosotros”.

Entonces, vemos esa reinterpretación del legado de Hussein. Y es por eso que el día de Ashura 7 de diciembre de 1978 fue el mayor acontecimiento de protesta en la historia de la revolución iraní. Entre 10 y 15-17 millones de personas. En un momento en que la población de Irán era de unos 34-35 millones de personas, es casi la mitad. Ese fue el acontecimiento de protesta más grande en la historia mundial. En un momento en que el sah había impuesto la ley marcial, con un Gobierno militar en el poder en Teherán.

Desde la revolución, el Gobierno iraní básicamente ha cooptado a Ashura, diciendo que “nosotros, como Gobierno iraní, apoyamos la lucha de David y Goliat. Somos los abanderados de Hussein al enfrentarnos a Estados Unidos en la región”. Y ellos… Esto es parte de la historia ahora no solo del islam, sino de la revolución iraní. Inculcaron esta lección a la próxima generación, que se crio bajo la autoridad del Gobierno iraní. El Ashura de 2009 luego explota en la cara del Gobierno iraní porque en el Ashura del 27 de diciembre de 2009, los manifestantes dicen: “Este mes es un mes de sangre. Ali Jamenei será derrocado. Este mes es un mes de sangre. Yazid será derrocado”. Así que ahora están equiparando al Gobierno iraní con los asesinos de Hussein en Ashura precisamente. Y al hacerlo, están usando ese lenguaje del islam y la revolución iraní contra el supuesto líder de la revolución iraní.

Jamenei, aunque no era el líder de la revolución, encarna la continuidad de la revolución. Uno de sus muchos títulos es el de líder de la revolución. Y fue entonces cuando el Gobierno realmente consideró a los manifestantes como blasfemos. Son sacrílegos, están violando nuestras santidades. Y muchas de esas sentencias de muerte que vemos que se dictan ahora, realmente las ves culminar en el levantamiento de seis meses en el Movimiento Verde, o siete meses, en el Movimiento Verde. Muchas de esas sentencias de muerte se dictaron a fines de diciembre, principios de enero, por esas protestas de Ashura.

Un último punto. Una de las cosas realmente interesantes de 2009 es que al protestar contra el Gobierno iraní en Ashura precisamente, sacaron a la luz una paradoja que existe en Irán. Hussain, en el siglo VII, murió combatiendo el poder. Nunca alcanzó el poder. En el ámbito internacional, Estados Unidos es la superpotencia mundial, la única superpotencia. Para Irán, el Gobierno iraní, liderar la carga contra los Estados Unidos en el Oriente Próximo podría jugar con ese mantra de Hussein como portador de la bandera de la lucha de David y Goliat, porque Estados Unidos es el detentador del poder en el mundo, y aquí está este Estado de resistencia luchando la lucha de David y Goliat. Pero en el Ashura en 2009, la paradoja es patente, porque dentro de las fronteras de Irán, internamente, el Gobierno iraní, que reclama el manto de Hussein, es el árbitro supremo del poder. Y los manifestantes estaban desarmados, enfrentándose al Estado, estaban invocando el legado de Hussain y enfrentándose al Estado.

A eso me refiero cuando digo que robaron al Estado todas estas bases de legitimidad. El Gobierno iraní desde 2009 es la sombra de lo que solía ser en cuanto a sus bases de legitimidad, y ha redoblado la represión. Está evolucionando y endureciendo su capacidad represiva porque no tiene la legitimidad que tenía antes de 2009, y para muchos nunca la tuvo. Pero si somos objetivos, era mucho más legítimo en 2009 de lo que es hoy por todo lo que ha pasado desde entonces.

Talia Baroncelli

Bueno, el régimen debe de haberse enfurecido increíblemente de que lo compararan con Yazid. Quiero decir, es como el tipo malo por excelencia. Así que probablemente por eso no les gustó mucho esa comparación. Pero creo que el Levantamiento Verde también fue un contexto ligeramente diferente, porque el contexto de los levantamientos era protestar por la elección de Ahmadinejad. ¿Y cuán importante fue [Mir-Hossein] Mousavi [Jameneh], el candidato de la oposición, en fomentar las protestas y apoyar las protestas en ese momento?

Pouya Alimagham

En realidad no era tan importante. A menudo hablo del Movimiento Verde cuando hablo de las protestas de hoy, y la gente no entiende por qué hago eso. Como historiador de los movimientos revolucionarios, en realidad es muy importante poder comparar y contrastar. Las protestas de 2009 comenzaron por los resultados electorales, y luego se transformaron en un movimiento antiestatal, anti-República Islámica. Como he dicho, pasaron de “¿Dónde está mi voto?” a: “El Gobierno de Jamenei carece de validez y debe ser derrocado”. Estas fueron las consignas. La protesta de hoy comenzó con el tema del hiyab y la muerte de una persona, y se ha convertido en algo mucho más grande. Evolucionó muy rápido.

Por eso es importante ver la continuidad. La gente lo ve como un líder. No lo era. Por supuesto, él era un candidato. Era un candidato reformista. Lo que la gente terminó haciendo realmente fue, antes de las elecciones, la gente pidió que se hicieran boicots, y hubo boicots en 2005, por eso Ahmadinejad ganó contundentemente en 2005. Se pidieron boicots nuevamente en 2009. Y mucha gente no quería boicots, por dos razones. Una es que piensan que votar en la República Islámica es un ejercicio fútil, porque todo está algo controlado, todos los candidatos pasan por un proceso de selección, y hay mucho de verdad en eso, claro. Pero las personas que vivieron durante los cuatro años del régimen de Ahmadinejad entendieron que cuando no votas, permites que continúe en el poder un excomandante del CGRI, quien luego nombra a los miembros del gabinete… Todos o la mayoría de los miembros de su gabinete eran del CGRI, y no tenían experiencia en el Gobierno, los comandantes del CGRI, lo que condujo a la prevalencia de las fuerzas de seguridad en el país mayor que nunca antes.

Entonces, cuando se propusieron los boicots en 2009, la gente no estaba entusiasmada con hacer boicots. No sabían qué hacer. Le estaban dando una oportunidad. Y luego vieron los debates televisivos. Habíamos tenido debates presidenciales en el país antes, pero esta era la primera vez que el formato era uno a uno. Cuando se enfrentaron cara a cara, Mousavi versus Ahmadinejad, a pesar de que había cuatro candidatos en total, los debates entre Mousavi y Ahmadinejad fueron realmente intensos. Mousavi acusó a Ahmadinejad de todo lo que muchos iraníes habían estado diciendo entre ellos, y ahora de repente lo están viendo en la televisión nacional, sobre la corrupción, la securitización del Estado… Mousavi dijo: “Cuando va a la televisión y habla sobre el Holocausto y cosas así, nos está avergonzando. Es una vergüenza para nosotros en todo el mundo. Ha arruinado el nombre de Irán en todo el mundo”. Y la gente se identificaba con lo que dijo Mousavi. Después, muchos de los activistas utilizaron su campaña para movilizarse contra el Gobierno. Antes del día de las elecciones, ya se oían consignas en Teherán que decían: Marg bar Taliban, che dar Kabul, che dar Tehran. “Muerte a los talibanes, ya sea en Kabul o en Teherán”. Esencialmente equiparando el robierno clerical en Irán con uno de sus archienemigos, los talibanes en Afganistán.

Entonces, vemos eso. Y luego, cuando ocurrió el fraude electoral, o Ahmadinejad supuestamente obtuvo una victoria electoral, empiezas a ver un amplio movimiento de protesta que realmente no tenía nada que ver con Mousavi. Mousavi no lo estaba pidiendo. Muchas veces, cuando ocurrían protestas, él se unía a ellas después. Sí apareció en una protesta importante. El lunes siguiente, el 15 de junio, aparece entre la multitud. Pero apareciera o no, iba a suceder.

Y luego, cuando la protesta fue aplastada después de una semana, comienza a resurgir en días específicos de Ashura, cuando el Gobierno fue relajando la represión para lograr que sus simpatizantes salieran. Como el aniversario de la toma de la Embajada de EE. UU. En esos días, el Gobierno iraní quiere que la gente salga, pero que salga a protestar con el Gobierno, no contra él, con el Gobierno contra Estados Unidos. Y en esos días en que se relajó la represión, los manifestantes del Movimiento Verde resurgen y reavivan el movimiento de protesta. Eso no tenía nada que ver con Mousavi. Esa estrategia, esa táctica, cogió a Mousavi y a ellos mismos por sorpresa.

Están haciendo cosas así hoy. Están pidiendo a la gente que actúe. Eso es algo que forma parte de la cultura iraní. Como he dicho, el Ashura de 1978 fue el día de la acción política, cuando murieron manifestantes en la revolución iraní. El día 40 de lamentación pasó de ser un día en que visitaban la tumba a un día de protesta. En el día 40 de la muerte de Mahsa Amini, la gente activó esa cultura, ese ritual, por razones políticas. Eso es algo integrado en la cultura iraní. En la cultura iraní e islámica hay ciertos días, ciertas cosas culturales, que pueden o no ser políticas. Depende de lo que quieres hacer con ellas. Es algo así como un acervo cultural donde podrías activarlos políticamente, con objetivos políticos. Pero no tiene nada que ver con Mousavi ni liderazgo ni nada. Eso es solo parte de la historia y la cultura iraníes.

Talia Baroncelli

Bien, quería hablar sobre el tipo de estructuras, la estructura política de la República Islámica, porque creo que algo que surgió de la revolución fue esta enorme estructura de Gobierno extensa, interconectada, interrelacionada, que depende… Vemos al líder supremo y luego el funcionamiento de Jomeini, y después Jamenei, dependía realmente de la Guardia Revolucionaria, el CGRI, y luego el cuerpo paramilitar [Nirouyé Moqavematé, Fuerza de Resistencia] Basich. Así que me preguntaba, ¿crees que sería necesario que se produzcan deserciones en todas estas instituciones iraníes? O si se producen más deserciones en una, ¿sería eso suficiente para derrocar al régimen desde dentro?

Pouya Alimagham

De nuevo, estas son cosas difíciles de predecir. Pero el Gobierno iraní… Diré esto: el Gobierno iraní, a pesar de todos sus fracasos, ha creado un sistema que es casi a prueba de golpes de Estado. Es a prueba de golpes hasta cierto punto. El Consejo de Guardianes [de Constitución de Irán] selecciona a los candidatos presidenciales y parlamentarios y abusa de ese poder. Pero también significa que ningún candidato respaldado por Estados Unidos o extranjero podría presentarse a un cargo.